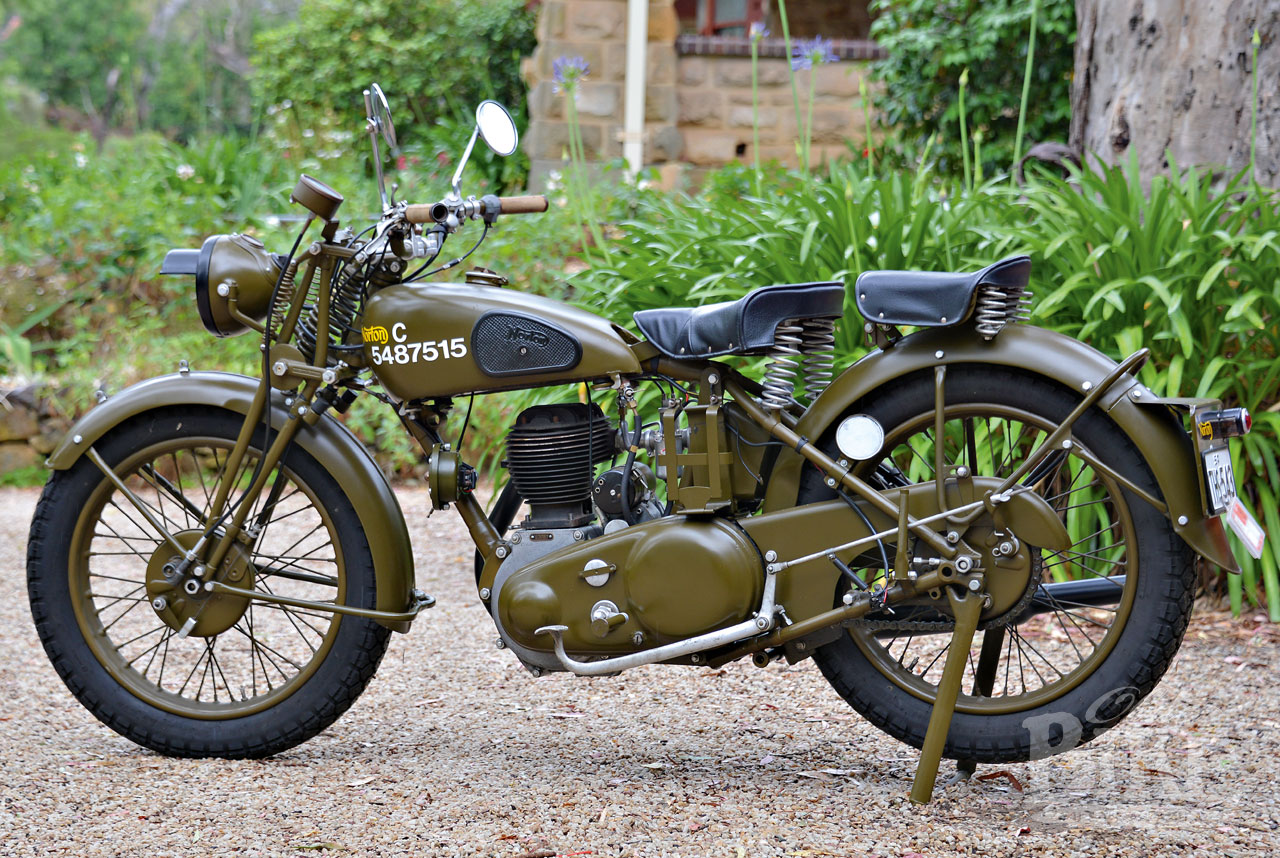

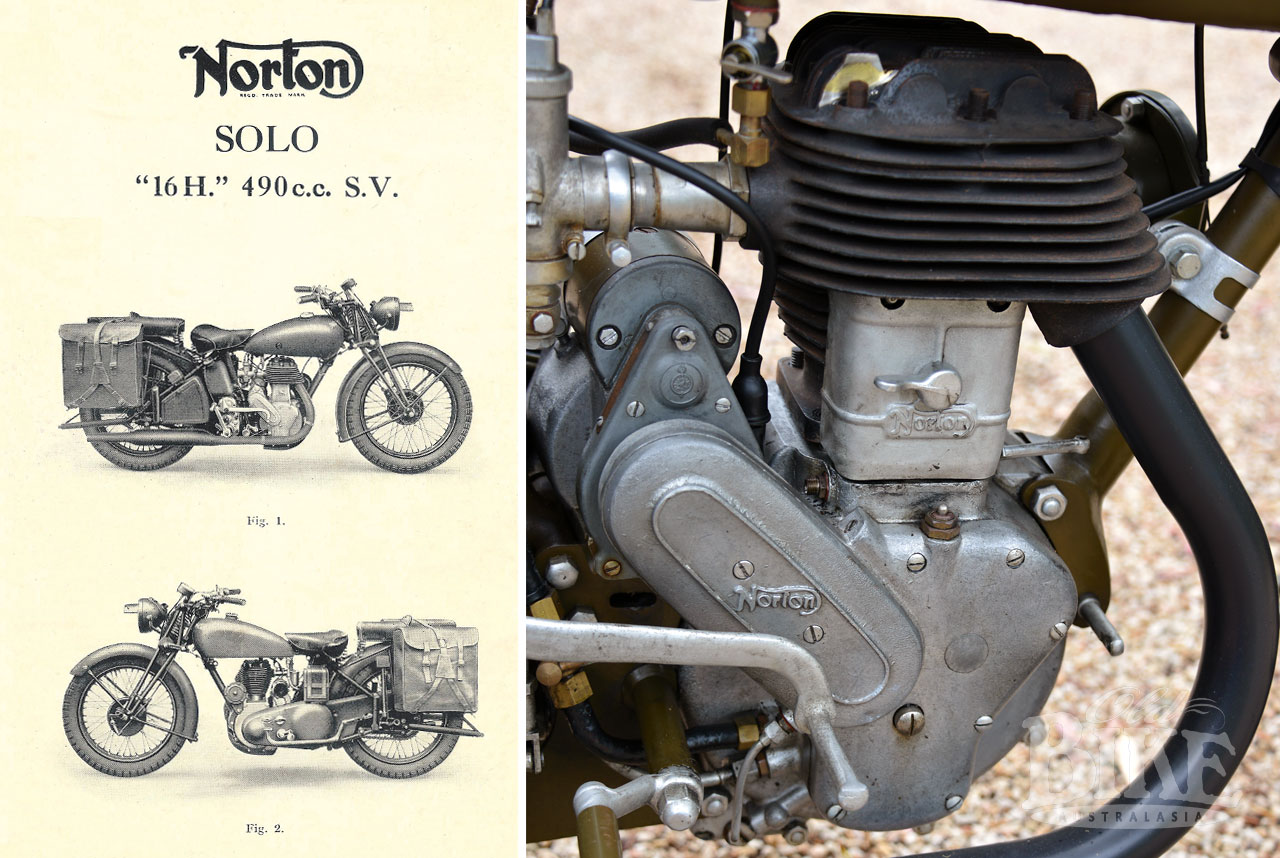

79mm x 100mm may well be the most famous bore and stroke in motorcycling history. Countless Norton singles, beginning with the 1911 490cc side valve, belt-driven Model 16, shared the configuration which lasted until the end of single cylinder production in 1963. That’s not a bad run, but in between times, the 16H earned a reputation as the favoured British military motorcycle of the Second World War.

Story and photos Jim Scaysbrook with much input from Rob Elliot

In fact, the 16H’s days in khaki started well before WW2, with the first order placed by the War Department in 1936, and the final deliveries made a full decade later. And it wasn’t just the army that took the 16H, with the Royal Air Force ordering hundreds which, prior to 1939, were painted in the distinctive RAF blue-grey, while the Royal Navy ordered theirs in RN grey.

Harking back to the beginning, James Landsdowne Norton established the Norton manufacturing Company in his native Birmingham in 1898, initially making fittings for the established cycle industry and the nascent motorcycle side. It took only four years before Norton produced a motorcycle bearing his own name, a bicycle-like device with a French Clement engine mounted on the front downtube, a two-speed countershaft transmission and all-chain drive. Norton developed his technical skills making toolwork for the jewellery trade, and built his own steam engines in his spare time. He was by all accounts a ruthless taskmaster, who would tolerate nothing short of perfection from his own workers.

Although he suffered from poor health all his life and died at just 56 in 1925, ‘Pa’ Norton nevertheless raced in three Isle of Man TTs from 1909 to 1911. The Norton TT tradition had begun at the very first event in 1906 when Rem Fowler won the Multi-cylinder class on a Norton with a twin-cylinder Peugeot engine, but by 1907 a prototype 660cc side valve single, called the Big 4, was up and running. That first design was fairly straightforward, with head and barrel cast together in iron, with a circular aluminium alloy crankcase and the magneto mounted on the front of the engine driven by a chain from the exhaust camshaft. A visual feature was the exhaust pipe, which emerged almost vertically from the exhaust port and ran down to a cylindrical silencer mounted transversely in front of the engine. By the time the Big 4 reached production in 1908, the stroke had been reduced from the prototype’s 125mm to 120mm, with a 82mm bore, giving a capacity of 633.7cc.

In 1909, a smaller version appeared, retaining the 82mm bore but with a much shorter 90mm stroke for a capacity of 475cc. Pa Norton himself rode the new model in the TT that year but retired from the race, as he did in the following year. For 1911 – the first year of the Senior TT for 500cc machines – the engine was completely redesigned to the 79mm x 100mm dimensions, but unfortunately his luck remained unchanged with another retirement which brought down the curtain on his TT career. The 490cc version became known as the Model 16 in a fairly confusing model numbering system.

The Big 4 and its smaller brother sold well, but not well enough. Pa Norton’s continual pursuit of quality regardless of expense was clearly a bad business practice, and the end came for the company in 1913. One of the main creditors in the liquidation, R.T. Shelley, took over and renamed the company Norton Motors Limited, retaining the founder’s services while accountants now kept a close eye on finances. Norton remained afloat during the First World War, producing military components and as many motorcycles as it could under the circumstances. Development was mainly confined to the transmission department, with a three-speed Sturmey Archer gearbox being tested and eventually fitted as standard, either with chain or belt final drive.

It was 1921 when the 16H model was first catalogued. The main difference to the 16, which used the Big 4 frame, was a lower frame that had been built for, and used in, the 1920 TT. The ‘H’ stood for ‘Home’, as in market, while the export model, with the original frame, became known as the 17C (C for Colonial). Adjustable tappets appeared in 1922, eliminating the need to file the valve stem to obtain correct clearance, and in the same year an all-new overhead valve design appeared, still using the 79mm x 100mm dimensions, which was eventually marketed as the Model 18. The racing version of the new ohv engine finally achieved what the company had been trying to do since 1906 – win the Senior TT with its own engine. Alec Bennett was the rider who took the victory in 1923, and Norton had a double reason to celebrate when George Tucker, with the engineer Walter Moore as passenger, won the Sidecar TT by almost 30 minutes.

While the racing lads went crazy with the Walter Moore-developed overhead valve engine, and the subsequent overhead cam CS1, the firm’s bread and butter continued to come from the side valve models. As the ‘thirties dawned and development of the new overhead camshaft engine continued apace under Arthur Carroll, who took over when Walter Moore left to join NSU, taking his ohc design with him, the road-going singles received a major makeover as well. The 16H, along with its ohv brothers the Models 18, 20, 22 and ES2 retained the 79mm x 100mm dimensions, but in other respects the engine was new. In keeping with current fashion, the magneto was moved to behind the engine on the 16H, dry sump lubrication (with a new gear oil pump that was to become a Norton signature) adopted and detail changes made to the cylinder head, and the frame finally brought into line with the opposition and much more modern looking.

As early as 1932, a specially-prepared 16H had been provided for military evaluation, along with a 500cc ohv Model 18 and a 600cc ohv Model 19. After extensive testing, the side-valver got the nod and Norton and the war Department collaborated on the final specification for what would be known as the WD16H, of which almost 5,000 were built and delivered prior to the outbreak of war in 1939. Rather than turn the factory over to the manufacture of munitions or military parts, as many of the existing British motorcycle companies had done, Norton boss Gilbert Smith was determined to continue with the company’s core business – making motorcycles. Looking far into the future, he reasoned that Norton would be in far better shape when peace resumed if there were to be no break in motorcycle manufacture, and to this end he strongly petitioned Whitehall in the late 1930s to urge them to order army-spec Nortons in large quantities. The pacifist government were at that stage fully expecting ‘peace in our time’ and dismissed Smith’s overtures, so Smith switched his efforts to the army itself, to the point of inviting top brass to events like the TT, the International Six Days Trial and the Scottish Six Days Trial, or any other event where Norton riders could be seen to be dominating. He also supplied extensive and continuous reports on Norton’s sporting successes.

By 1937, when the threat of war was becoming increasingly real, Smith’s persistence paid off and Norton received an official War Department contract for the supply of motorcycles. The 16H had by that stage been developed with enclosed valve gear, but the WD model used the original open valves, with the engine mounted in the frame that Norton had developed for trials with extra ground clearance, and girder forks with buffer stops. The WD16H immediately proved to be exactly what was required; robust, reliable, and easy to maintain. It was also relatively inexpensive to manufacture, which did Norton no harm at all. Around 100,000 16H models were to be manufactured for the war effort.

“Step forward C 5487515!”

Rob Elliot has an amazing collection of motorcycles, dating from veterans to the comparatively modern, and they all hold a special significance, none more so than his Norton 16H, which currently bears the army serial number C 5487515. “It was Inevitable that I would become interested in military motorcycles from WW2. Dad was in the 2/27th Battalion and served in New Guinea and Borneo”, says Rob. “My childhood was full of war movies, docos and personal stories.

“Much to mum’s disgust, Dad would give me military-related toys such as the fantastic toy 303 rifle I had with working sights and bolt action; the Norton 16H is just a slightly bigger toy. This childhood influence is no doubt also partly responsible for my eventual career in landmine detection technology.

While living in Darwin in my early 20s I came across a job-lot of old rigid frame Norton parts, which I bought from well known NT speedway rider Chris van Eck. Amongst it were some Big 4 and 16H parts which kindled my interest in these earlier creations of Norton. After returning to Adelaide to study Product Design at uni I bought a couple of basket case Norton side-valves from an old gentlemen at Cambrai in South Australia’s mid-north. He’d been a rural vermin inspector and had amassed a large quantity of old bikes from his travels. These were more complete than the bits I’d bought in Darwin, but still quite a challenge.

“As luck would have it, not long after the Cambrai purchase I found a complete 16H in Adelaide and snapped it up as a much easier restoration project, even though it had been dismantled into large chunks. I found out it was a WD model by the matching engine and frame numbers – prefixed with the letter W. This indicated it was made by Norton as a purpose-built War Department machine built to an army specification and contract, rather than a conscripted (privately owned) bike just leant against a wall and painted green.

This particular WD16H had been “civilianized”, as most were after the war. It had been painted black and the army fittings (such as the special headlight) replaced by civilian ones.”

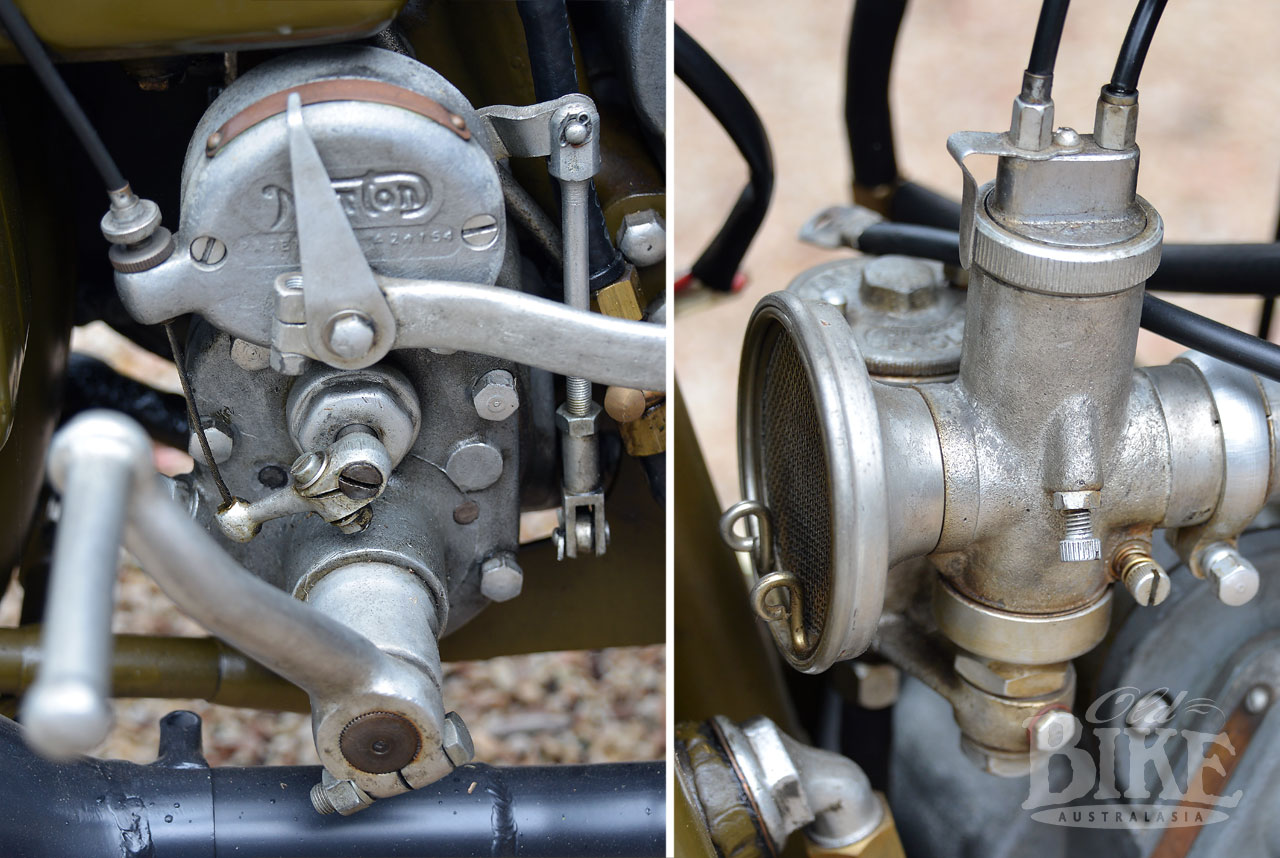

Even in the late 1980s, military parts were relatively easy to come by, as there were caches of such parts in places like India and Malaysia. Rob set out to find the necessary bits which included the ‘blackout’ headlight, steel footpegs with no rubbers, the special rebound bumper assembly for the front forks (fitted to absorb major shocks such as falling into trenches and potholes), canvas (not rubber) hand grips, an offset speedo bracket so the speedo cable would not get trapped in the forks, a speedo without a trip-meter, and a headlight switch with an extra “T” for tail light position so that only the tail light worked during convoy missions.

Rob found the original engine a bit tired, but a friend had a new engine with an army service plate attached to it, which was cleaned up and fitted, although Rob plans to eventually rebuild the original engine and fit that.

“The paint colour was matched to the remnant paint samples I found on some of the original parts I had from the Cambrai purchases. The spray painter I used, an old craftsman named Les Hall, did most of the motorcycle work in Adelaide at the time and by sheer coincidence also used to work with my father in the Public Building Department as a sign writer. Les found that the army green was still a current paint code – so the only thing to get right was the gloss level – which, going by period photos, he got spot on. They weren’t a matt finish as some people paint them. A friend who used to make replica Lycette saddles and supply most of the Australian restoration market, John Whellum, refurbished the seats for me.

“I have plans of doing a refresh of the restoration in the near future. I plated most of the metalwork with cadmium as the local “experts” all insisted that Norton used this finish at the time (for both civilian and Army machines). I’ve since found out, through research and finding new old stock parts, that this was just a myth. Norton used dull chrome on most fasteners and fittings (except for the occasional splash of bright chrome on things like pushrod tubes and headlight rims). Dull chrome was used extensively on the Army models. The exhaust on the Army Nortons manufactured by the factory, for example, was entirely dull chrome plated. The Cadmium plating on the exhaust didn’t take the heat and has since been sprayed satin black, so I intend to redo my exhaust in this correct finish during the refresh. I’ll also replace the army registration number on the petrol tank and number plate. When I was younger vinyl stick-on letters seemed acceptable – now they just grate on my nerves. I’m also in the process of trying to find the original army registration number assigned to this bike. The number that’s on there at the moment was one I found under layers of old paint on a petrol tank I had from one of the Cambrai basket cases and so decided to use it, at least knowing it was a real Army registration number assigned to a Norton.

“I started looking through the Army registration records at the Australian War Memorial Research Centre while in Canberra for work last year. Unfortunately it’s a laborious task as the records aren’t in engine number sequence, or blocks of manufacturers’ makes, but in army registration number sequence i.e. C ?????? mixed up amongst BSA M20s, Jeeps and trucks. I had to leave the search unfinished in order to catch a flight home – so the continuation of the search may have to wait for the next trip to Canberra. I was told at the Research Centre that the original Army log books that accompanied each bike, and provided its service history, were unfortunately all destroyed some time shortly after the war. Looking through the records it was apparent that the only war service information that was going to be obtained from the existing records is what registration number was assigned to a particular engine and frame number and whether it was assigned to the RAAF or AIF and to some extent what happened to it after its war service period. The records show that a lot of the machines were sold to dealers such as Milledge Brothers in Victoria, or Hazell and Moore in NSW.

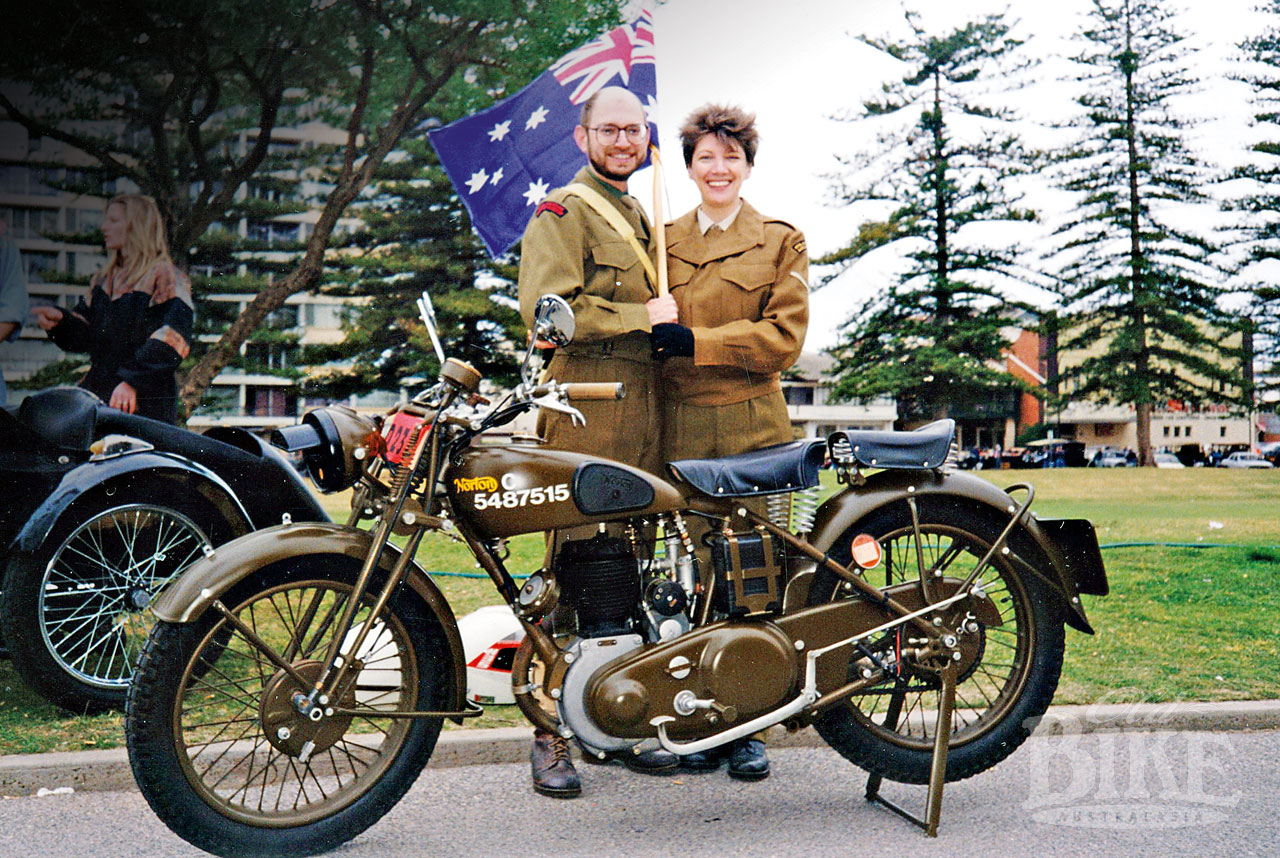

“Given that no-one can know what unit an army bike actually served with, I’ve got thoughts of painting my father’s battalion insignia on the bike – the brown and blue diamond of the 2/27th.

“The restoration took me two years and was completed in 1992. I’ve ridden it on a number of long runs such as the Bay to Birdwood and Burra to Morgan events since. The restoration of the bike was completed just after I met my wife Diana. A lot of our early dates were with Diana on the back of one or other of my bikes. Being interested in history herself and having grown up with motorbikes in her family, she didn’t hesitate getting into the spirit of things, donning an army uniform and going pillion numerous times on these lengthy runs. It wouldn’t be a particularly comfortable ride I would imagine, given the size of the small sprung pillion seat mounted on the rear mudguard (there were no complaints from Diana however). Parts of the uniform we wore were my father’s old army gear. I wore my father’s slouch hat (when not riding the bike of course) and we both wore his gaiters and belts.

“Riding the bike is a real pleasure, it’s light and easy to handle, yet torquey and surprisingly quick. I’ve owned Vincents, with the kudos they carry, as well as other sought-after and performance bikes, but the 16H is always more fun. There are plenty of Norton WD16H fanatics (and BSA M20 for that matter), especially in Europe. There are events such as recreations of the Normandy landings for these enthusiasts to participate in. For everything you could ever want to know about Army Nortons you can’t go past Rob Van Den Brink’s Dutch website www.wdnorton.nl (thankfully all in English).”

Rob’s correct about the fascination with ex-military machinery, particularly motorcycles. As well as the Nortons, you’ll find BSA M20s, the ubiquitous G3L Matchless, and even Velocettes all wearing their war paint at various rallies, plus of course those from the opposing team – notably Zundapps and BMWs. If only they could talk.