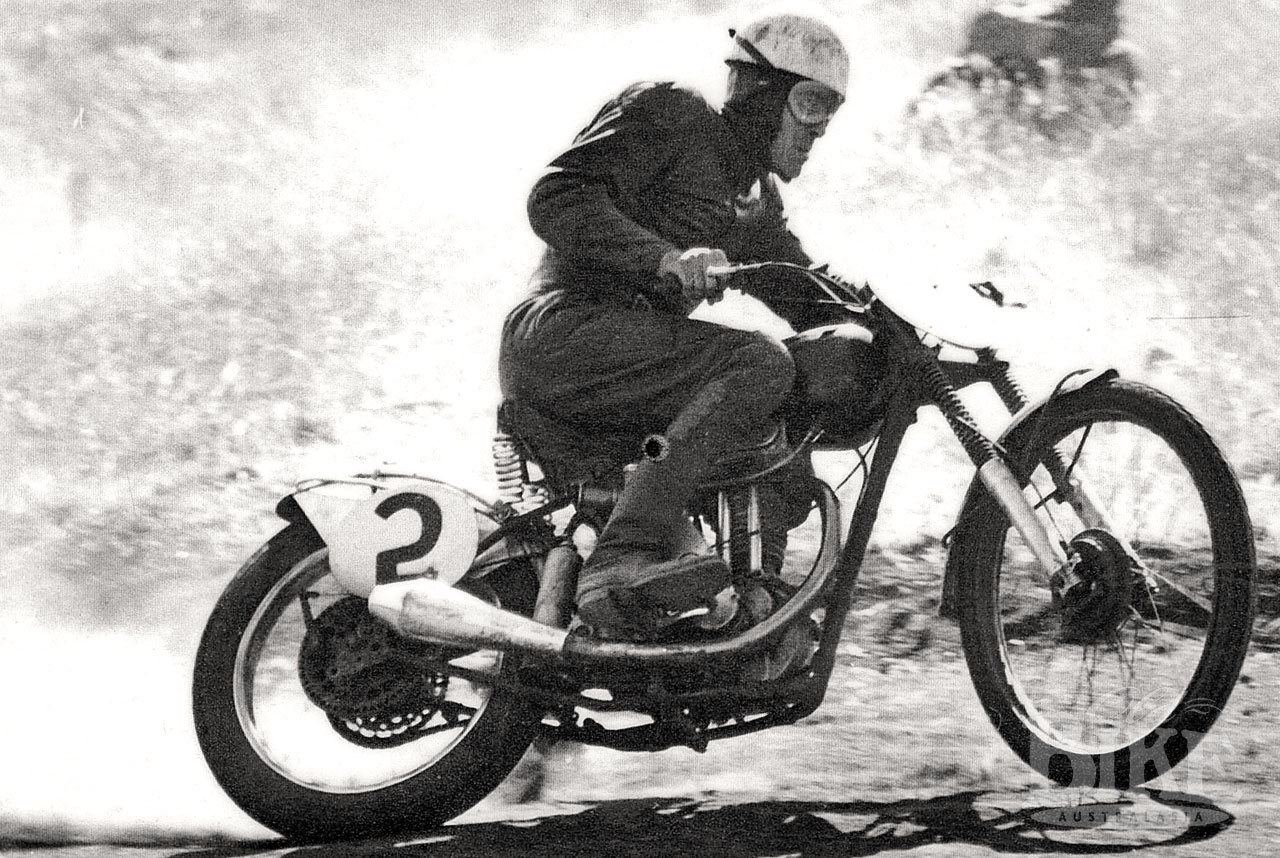

People have been trying to keep up with Tony Edwards for decades. Now, at 87, it is still a difficult task. Fit, sharp and entertaining, Tony’s life is as busy as it ever was, with a home workshop bursting with projects and a nice collection of motorcycles that he has either rebuilt or created as specials in his own inimitable style. But the queen of the bunch is still the 350 cc Matchless, affectionately known as Betty, on which Tony was virtually invincible on the dirt tracks of his native Queensland.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Tony Edwards archives.

Betty started life as a genuine rigid-frame 350 cc Competition Model Matchless in 1951, but over the years was developed into a demon machine that bristled with the Edwards touch. The engine sports his own barrel, cast in a half-gallon paint tin in his back yard, but inside things are really different. The original long-stroke dimensions of 69 x 93 mm were altered to 74 mm x 78 mm – the same as a KTT Velocette. Meticulous attention to weight paring brought the tare down to just 90 kg, and with the ever-aggressive Tony in the saddle, very few competitors saw which way it went.

Tony Edwards was born in England in 1924, but came to Brisbane as a youngster with his family. “I had my first race at Strathpine in 1948 on a 1936 Model 19 Norton 600 which had rebound springs on the front forks. It was eight-tenths of a mile up and back the air strip, and naturally I didn’t get anywhere on the old Norton, but soon after I got hold of a BSA Gold Star and started to go better.” In 1950, the real fame and fortune lay in speedway racing, and Tony tried his hand at that, but only for one season. His oval career at the Exhibition Grounds started badly when he hit the fence in his first race, and he never acquired a taste for that branch of the sport. The catalyst for change came one day at the Oxley Miniature TT circuit, where Tony was riding his BSA as a B Grader. Austral ‘Duck’ Anderson had fallen and hurt his wrist, so Stan Sharp, the chief general manager for Anderson agencies, who handled Norton, Panther, Excelsior and Jaguar cars asked Tony if he would like to ride Duck’s rapid Norton in the A-Grade Final. Tony jumped at the chance, finishing second, and was offered a job on the spot. “ Cyril Anderson had a huge business,” Tony recalls, “with Mack and Dennis trucks, transport companies and the various agencies, all based out of Toowoomba. Cyril had raced speedway in the 1930s and his brother ‘Duck’ Anderson was a good rider. His wife Geordie had an XK120 Jaguar that she used to race and she was quite good at it as well.”

A well-travelled 1948 350 cc Manx Norton was next on Tony’s list. “Someone had bought it in Darwin and ridden it to Brisbane, then traded it in on something. I saw in laying down the back of Bob Todd’s workshop, all covered in dust, and I bought it, stripped it down and set it up again, put a shorter rod in it and raced it – went like the clappers,” he says. Working for Andersons had its rewards, as a SOHC 500 ‘Garden Gate’ Manx also came his way, which Tony fitted with a DOHC head and cam box. The biggest post-war meeting to be held in Queensland was the 1951 Australian TT at Lowood on June 11. Being the country’s top event, it attracted a big field of stars from interstate, including Sid Willis, Jack Forrest, Laurie Hayes, Lloyd Hirst, Bill Morris and Maurie Quincey. In the 100-mile Australian Jubilee Open TT, Forrest held a commanding lead until a broken fuel pipe from the auxiliary tank mounted on his Vincent sprayed the rear tyre and he crashed, leaving Bill Morris with a narrow lead over Tony. At two-thirds distance Morris shot into the pits to refuel, hoisting Tony into the lead, but with insufficient fuel to go the distance he was forced to pit with just two laps remaining. In his haste, Edwards failed to stop his engine, as required under the rules, and although he took the flag in second place behind Laurie Hayes, he was disqualified after a protest was lodged by Perc Quincey, Maurie’s father; the result moving Quincey to third. It was a bitter blow after a brilliant ride when he matched it with the best road racers in the country.

Tony’s plunger-framed Manx continued to give good service with consistent results at meetings at Lowood, Strathpine and Leyburn, and he rather fancied his chances of landing a ride on the pair of new Featherbed Manx Nortons imported by Anderson’s in 1952. It was therefore a major disappointment when the new machines were allocated to Clive Nolan. He recalls a meeting at Lowood when he finally got to straddle the swinging-arm framed Manx. “The final race of the day was a handicap and I was preparing to go out in that when Ted Glanville, the manager for Anderson’s spotted that the frame had broken in two places, as they often did on the Garden Gate frames. Anyway, he told me to take the 350 Featherbed Manx that Clive Nolan usually rode and I started off the scratch mark with Harry Hinton and Forrest. I beat all the 350s but couldn’t keep up with the 500s, but the handling of the Featherbed was a revelation. On the plunger frame, you turned it into a corner and by the time you actually got there you were OK, but on the Featherbed you turned it and that’s where you went!”

The Norton association continued to bear fruit for Tony, and he was recruited for a series of record attempts at the ex-wartime airstrip at Leyburn, west of Brisbane. The squad comprised the 350 and 500 Featherbed Manx Nortons for Clive Nolan, plus the Garden Gate 500. “To contest the Sidecar class, I had to put a chair on the Garden Gate Manx, and ballast of 148 pounds in the sidecar. I drove out to Leyburn with Geordie in the XK120. She was going to attempt some records too, and we sheeted the underneath of her car to reduce wind resistance and installed new camshafts. To get a decent run, we cut down a span of fence to the side of the cattle grid that went into the property. I got about 60 yards back down the road with the chair and poured it on and started heading for the gap. But with the drag of the sidecar it drifted me across and I started heading for the fence post on the left. So I shut it off and swung it around and went back 100 yards and came back, aiming for the post of the right side this time, just drifting nicely and I knew I was going through. I got six new sidecar records that day.”

The Norton connection came to an end when Tony joined Markwell’s, the Matchless agents, in 1952. As well as a position in the workshop, the deal involved a new Competition model 350, plus a 500 fitted with a genuine Shelsley Walsh engine. Both bikes were rigorously tested in the workshops and ended up being the fastest bikes on the very competitive Miniature TT scene. “Roy Markwell was the workshop manager and I built a test bench using an old car chassis, with an A-frame and the car diff mounted in that. In place of the crown wheel we had a sprocket and the bike was bolted into the frame without a back wheel and the chain running to the diff. We built two big paddles to act as an air brake, and we would grind our own cams and watch the revs to see if they made any difference. We reckoned we were getting 42 horsepower at 7,000 rpm from the Shelsley – we reshaped the inlet port to give better gas flow around the valve.”

With his brace of Matchless machines, Tony racked up an incredible string of successes on the oiled-dirt courses, and rode in many scrambles event as well. In late 1953 he accepted a nomination from the ACU of Queensland to represent the state at the inaugural Australian Scrambles Championships at Korweinguboora, near Ballarat in Victoria, with a warm up event at Moe the previous week. True to form, both meetings were a mud-bath – conditions totally unfamiliar to Tony – and although he gave a good account of himself he was unplaced in the title events.

Back home, his dominance on the dirt tracks continued unabated, but he was keen to get back on the tar and he felt his chance had come when Markwell’s imported one of the new twin cylinder Matchless G45 racers in late 1954. He remembers the day well. “I was really hooked on racing and when the G45 arrived I really believed it was for me to ride. We assembled it and took it out the front of the shop for photos and I was going to start it so everyone could hear it run, but then Fred (Markwell) said, ‘Don’t start that bike, someone has just bought it.’ My jaw hit the deck. I came home and talked to my wife Joyce and we decided there and then we would start our own business, which we did in February 1955. We ran that business until February 1990.”

Tony continued to race the 350 and 500 cc Matchless Dirt Trackers, on which he chalked up win after win. But there was also a highly successful resurrection of his road racing career, thanks to businessmen Jack Costello and Pat Murphy who had a saw-milling operation at Inglewood. “They were very well off and owned several racing cars including the ex-Arthur Rizzo Riley. They also acquired a Cooper car from the Andersons which came without an engine, so they went looking for a Manx motor. Bill Anderson (Cyril’s son) had brought back a long-stroke 500 Manx from UK which he rode in the Australian TT at Longford in 1953. The bike was very fast, and Anderson finished to a close second to Maurie Quincey and recorded the fastest time of the meeting on the Flying Mile. Jack Costello bought the bike to get the engine out of it for the Cooper. Then when the 1955 Australian TT was awarded to Queensland (Southport) Jack rang up and asked me if I would like to ride it. I jumped at the chance. He said ‘I’ll send it down to you and you can keep it until we want it back’. The first thing I did was to pull the head and barrel off and check the big end – it was all OK inside and I set it up for methanol.”

At the TT, run on a particularly treacherous road circuit that ran around the fairly undeveloped Southport region, Tony rode a brilliant race to place second in the Senior TT to 20-year-old star Eric Hinton on his father’s ex-works Norton.

It seemed that Jack and Pat were in no hurry to get their machine back, because Tony continued to ride the Manx in local events over the next four years, culminating in the 1959 Australian Grand Prix which was run over a 1.2 mile circuit around Florida Gardens in Surfers’ Paradise. Still troubled by the after-effects of a serious shoulder injury sustained when he dropped the Norton at Lowood, Tony decided to run the Manx as an outfit, and staged a race-long dice with Orrie Salter in the Sidecar GP. On the final lap, Salter attempted a big move on the final left hand bend and his passenger, was flung out of the chair and into a telegraph pole and was killed instantly, as Tony raced on to victory.

Just prior to the Surfers’ meeting, Tony took out the Australian 250 cc Short Circuit Championships at Heit Park on his Maico. Markwell’s had recently taken on the agency for the German two strokes, and the range included a 250 cc Scrambles model that was similar to the road-going 250 Blizzard, and naturally Tony was chosen to ride it in Short Circuit and Scrambles events. This machine, although fast, was a source of constant frustration to Tony. “ The condensers would pack up and the points would carbon up. I lost so many races on it because of that.”

Tony took a year off racing after the Grand Prix, returning to win both Junior and Senior State Short Circuit Championships at Heit Park near Amberley, but that was his swan song on the dirt, and he expected, the end of his racing career. But in 1963, along came another temptation. In Britain, Ron Langston had taken out the Thruxton 500 Mile Race on an AJS 650 CSR, and Markwell’s imported the Matchless-badged version, a G12 CSR, and asked Tony to ride it. Tony recalls being extremely busy at work, too busy to run in the bike prior to its scheduled debut at the new Lakeside circuit. “A racing mate called in on the Saturday before the (Lakeside) meeting and said he would put some miles on it for me, and that’s all it did before the meeting, where I set the outright lap record, won the Production Race and finished second to Jack Ahearn in the main race. It was the fastest road bike in Brisbane for several years.”

The first motorcycle business run by Tony and Joyce Edwards was at Nundah, then they moved to Breakfast Creek Road, about 500 yards from the famous hotel, and next to Abbotsford Road, Mayne Junction. “We stayed at Breakfast Creek for three years, then the opportunity came to go to Domain. We were operating there for some time but then the floods came and wiped us out. There was seven foot of water through the place and it was three months before we got back into business. We had six guys working for us when the floods hit, but we got started again in 1974. As well as repairs, we had an agency for Yamaha, but when Brisk Sales took over Kawasaki and Annand and Thompson took Yamaha, we stayed with Brisk and Max Muller gave us the agency for Kawasaki and Maico.”

In the complex and little-understood field of frame straightening, Tony’s skills are legend. With typical ingenuity, he constructed his own jig. Over a period of 35 years, countless bent motorcycles received a new lease of life via surgery on Tony’s jig, which is still in use today.

With the sale of his business in 1990, it was time for Tony to take things a little easier, at least in theory. But it was merely a change of premises, because at the well-equipped workshop at his home, he has busied himself on many of his own projects. Tony and Joyce’s son Ross became a well-credential dirt track racer, aboard a Hagon Maico that was fettled by his famous father. Along the way he has built up a pair of very nice Norton Internationals, and has a string of other tasks lined up. And of course, pride of place in his collection is still ‘Betty’, the very special 350 Matchless that was the machine to beat for over a decade and brought Tony more successes than he can remember.