Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Byron Gunther, Trevor Evans, Keith Bryen

Wallace Anthony, or just plain ‘Tony’ McAlpine, died on the Queensland Gold Coast on September 26th 2005, aged 84. With his passing went perhaps the final link to the superstars of pre-war racing in Australia – an era when you needed to be able to master all and every condition imaginable, and face dangers that would be considered totally ludicrous today.

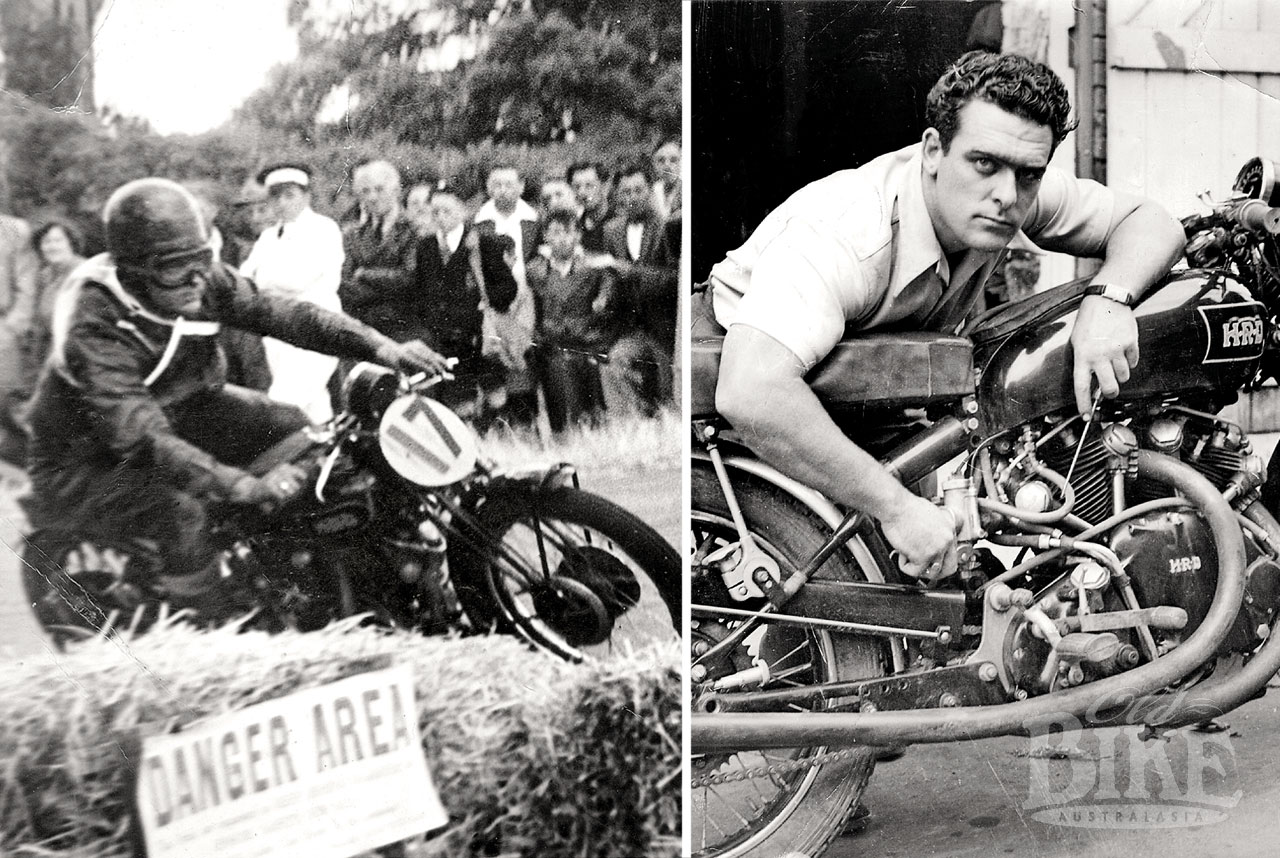

At the time of his introduction to motorcycle sport in 1937, Tony’s powerful physique and swarthy good looks, with dark brooding eyes and a shock of black wavy hair made him a standout figure. His mother Melita was Italian, an opera singer, and young Tony’s cultured baritone voice indicated he was headed for a similar calling. His father, Wallace, was a bank manager, and his grandfather Anthony held the position of Mayor of Fairfield, in Sydney’s western suburbs, for 13 consecutive years. Anthony Street Fairfield is named after him.

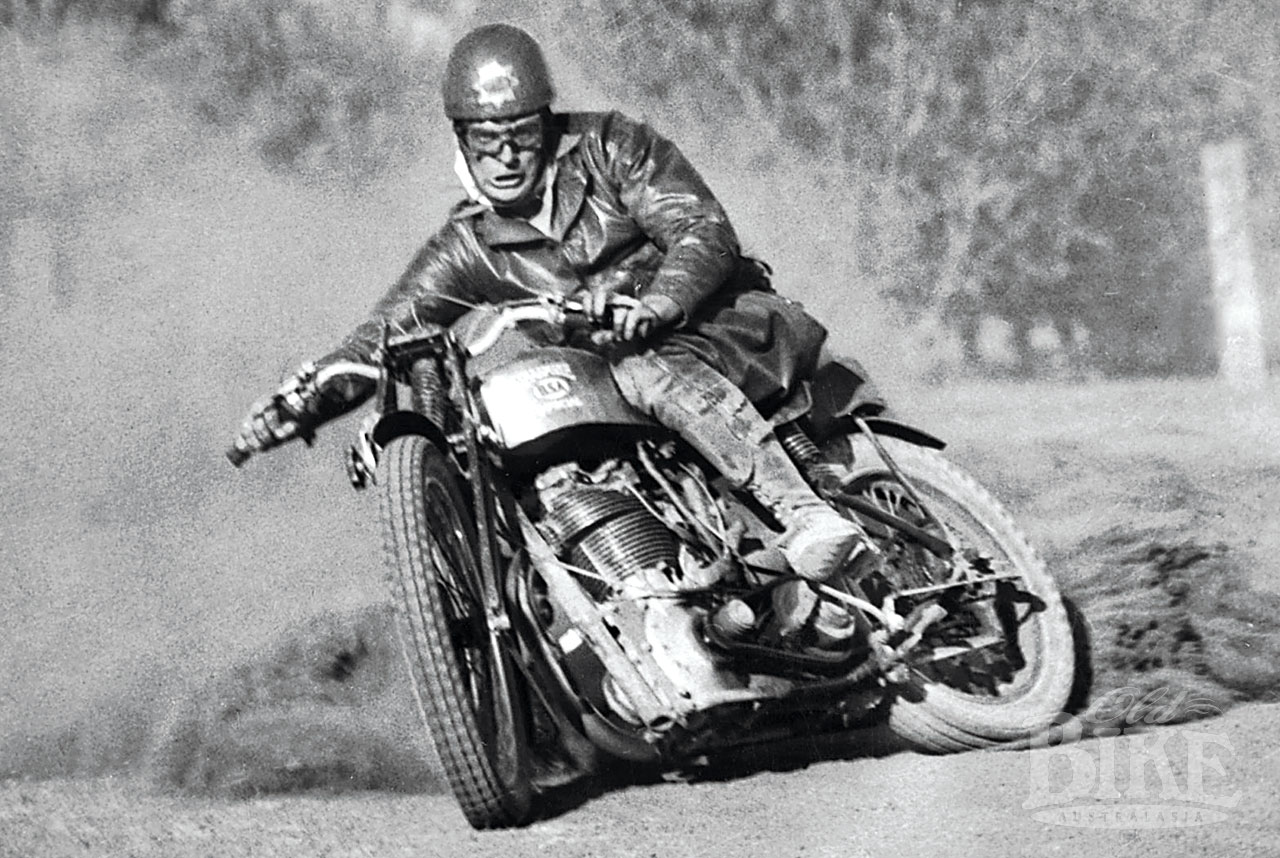

Even at school, Tony had little regard for authority, or for rules and regulations, and when he decided he wanted to go racing he had no intention of waiting until his seventeenth birthday to obtain a competition licence. At fifteen years of age he obtained the appropriate forms, added a couple of years to his age, filled out the section requiring parents’ consent, bought a 500cc BSA and a set of leathers, and went racing. Underage or not, he was a sensation from the moment he hit the track. Whereas most other top-line riders of the day tended to treat the dirt-surfaced Miniature TTs as a form of road racing, and kept things all neat and tidy, Tony reckoned the quickest way around was with the back hanging out, rear wheel spinning, and both wheels locked up in the corners. The two-wheel drift was his specialty.

The Boy Wonder

Dubbed ‘The Boy Wonder’ by the press, Tony plied the circuits around Sydney; The Poplars at Blacktown, Whynstanes and Little Brooklands, both at Smithfield, the latter promoted by his club, Fairfield Motor Cycle Club. From the outset, he wowed the fans with his all-action style, and was soon snapping at the heels of the star riders of the day – Harry Hinton, Eric McPherson, Art Senior and Bat Byrnes.

Mind you, their son’s new-found obsession with dirt track racing did not sit entirely comfortably with his family, who certainly had other career paths in mind. But the die was cast when Mayor McAlpine provided his grandson with a 500cc Gold Star BSA in 1938 – just about the ideal piece of equipment for an aspiring racer. The acquisition of the Gold Star shot Tony into the big-time. At Whynstanes in May 1938, just days before his seventeenth birthday, young Tony was hailed as the ‘find’ of the meeting. The Australian Motor Cyclist magazine’s scribe reported breathlessly…” I have seen many spectacular riders in my time, but never have I seen a TT rider ‘dirt-tracking’ corners as McAlpine did. …Scorning the use of brakes, and on a full-lock broadside first to the right and then to the left, McAlpine laid the machine from side to side using first one footrest and then the other to slacken his speed slightly…to witness him in action was definitely the grandest and most exciting exhibition seen on any type of racing circuit.”

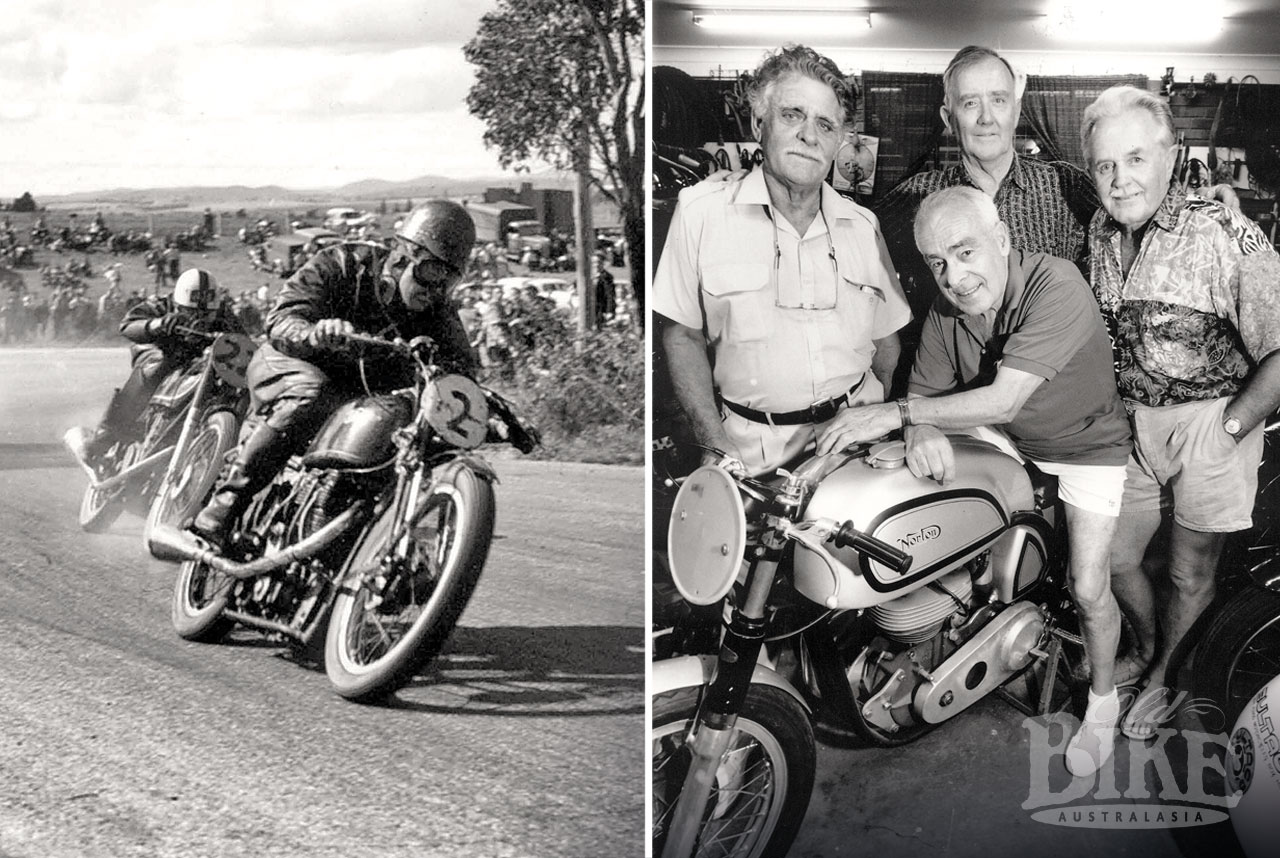

At the same track the following year he stunned the establishment by racing wheel to wheel with Art Senior, multiple Australian champion and holder of the Land Speed Record, in the feature handicap event, but even better was to come. The opening NSW race meeting for 1940 was held at The Poplars, and young Tony thrashed Byrnes, who was riding his Bathurst-winning OHC Norton, to win the Senior TT, the day’s premier event. The Australian Motor Cyclist magazine described the epic race thus… “These two riders fought it out like a pair of tigers, contesting every inch of the race on full throttle. On the last lap the crowd yelled with excitement…suddenly a huge cloud of dust appeared as Tony McAlpine broadsided into Blacktown Corner – who else could take a corner like that? One of the most sensational races every witnessed on any course.”

Tony McAlpine had really arrived, but unfortunately, so had the war. Virtually every form of motor sport ceased for the duration, except speedway, so Tony turned his hand to that. Soon he was in uniform, bluffing his way into breaking in horses (he said he always wanted to be a cowboy). It didn’t last; a broken leg forcing him into a less hazardous section. As a sergeant, he was put in change of the motorcycle workshop, where he also trained motor cycle commandos – everyone from privates to generals. Whenever he could get away, McAlpine raced at the Sydney Sportsground, but in his own words, “I never really got the hang of it”. He may not have thought so, but he more than held his own against speedway pros like Lionel Van Praag, Max Grosskreutz and the Duggan brothers.

On the road again

After his discharge, Tony bought a share in a taxi, operating from the Camden area in partnership with Dan Cleary. But the city was where the money was, so he moved to Maroubra, where he acquired an unrestricted taxi. There was plenty of money to be made in cabs post-war, with Sydney teeming with cashed-up American servicemen. Now it was time to resume the racing career.

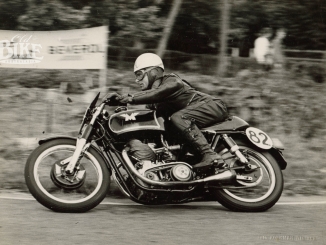

When the ex-Frank Mussett works 500 Velocette became available, Tony bought it, and turned to road racing with some success. But the machine that really skyrocketed him to the top was the Vincent Black Shadow which he bought in 1949. With his 185cm and 93 kg frame, the 1000cc v-twin was made to order for him, and he won the Queensland and Victorian Unlimited TTs in quick succession. Nuriootpa, in South Australia’s Barossa Valley, was the venue for the 1949 Australian TT on a sweltering Boxing Day. 5,000 spectators lined the three-mile road circuit to see Harry Hinton, who had already won the 350cc and 500cc titles, take on McAlpine in the Unlimited. Hinton flogged his 500 Norton mercilessly as he tried to stay with Tony’s Vincent, but it was no contest as Tony power-slid the big twin through the corners to set an outright lap record and win by just one second. The win that he most wanted – Bathurst, eluded him, but not without a moral victory in 1950. Pitting his self-tuned Black Shadow against Lloyd Hirst’s factory-built racing Black Lightning, Tony powered into the lead, not slackening his pace even when the strap on his goggles broke. Then, with the race in his pocket, the Vincent threw a chain on Mountain Straight and he was out.

Soon after, he made a quick trip to Europe to check out the racing scene, with the aim to return the following year as a competitor. There was no doubting Tony’s claim as the country’s top road racer, and he duly received the nomination as an official Australian representative to the 1951 Isle of Man TT. The appointment carried a cash payment, and an introduction to the AJS factory in England.

Into the big time

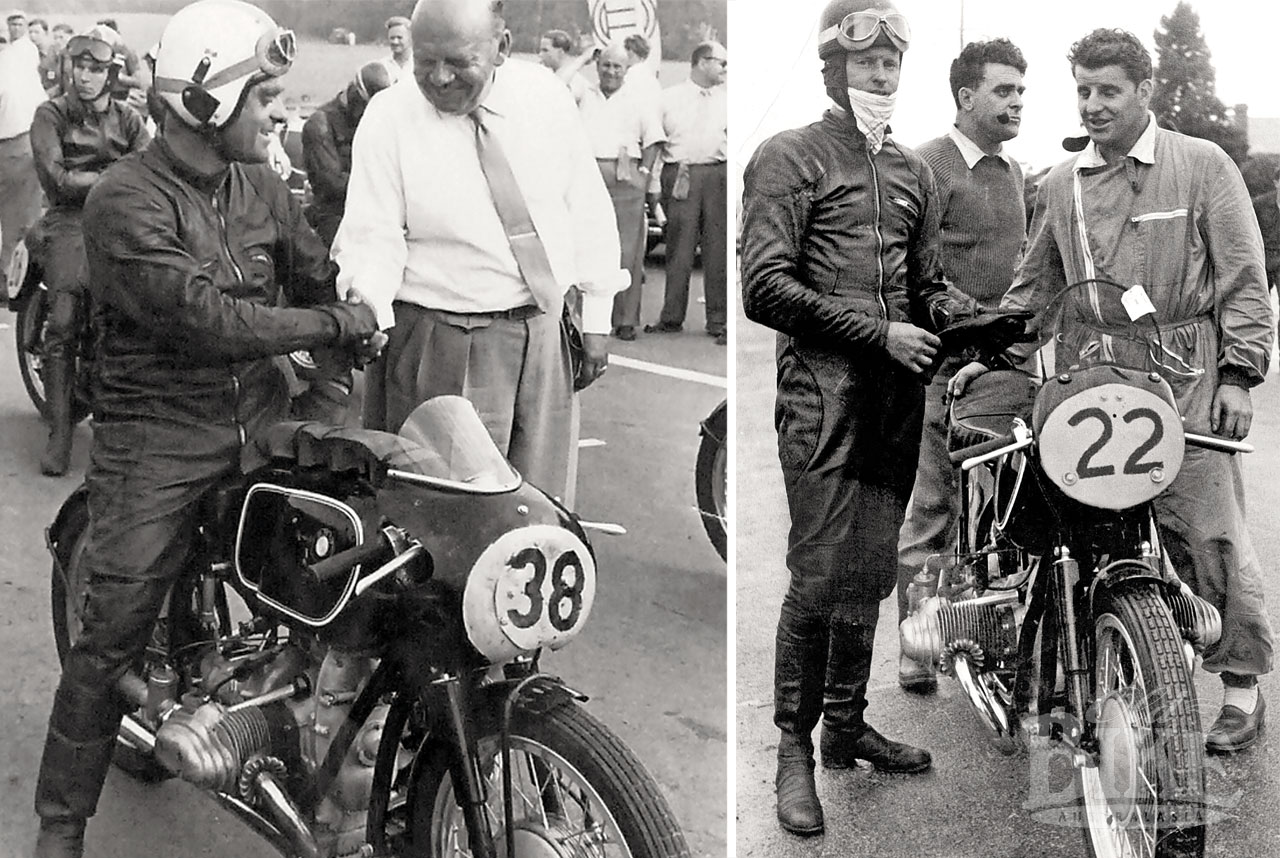

With his wife Vivian, Tony sailed to England in early 1951, with the offer of a position at the Vincent works as well as a schedule of racing appearances in UK and Europe. For the Junior class, he obtained a new 350cc 7R AJS, but he needed a 500 for the Senior. Figuring that his Italian heritage might count for something, Tony approached the Gilera factory in Milan for a machine, and received an encouraging response. He was convinced Gilera would sell him one of their fabulous four-cylinder racers, but when he arrived in Arcore to collect (and pay for) it, the machine turned out to be a single cylinder Saturno Sanremo. There was no time to argue. All the production Nortons were spoken for, so with only weeks before the Isle of Man TT, Tony reluctantly accepted the red machine and headed for Douglas.

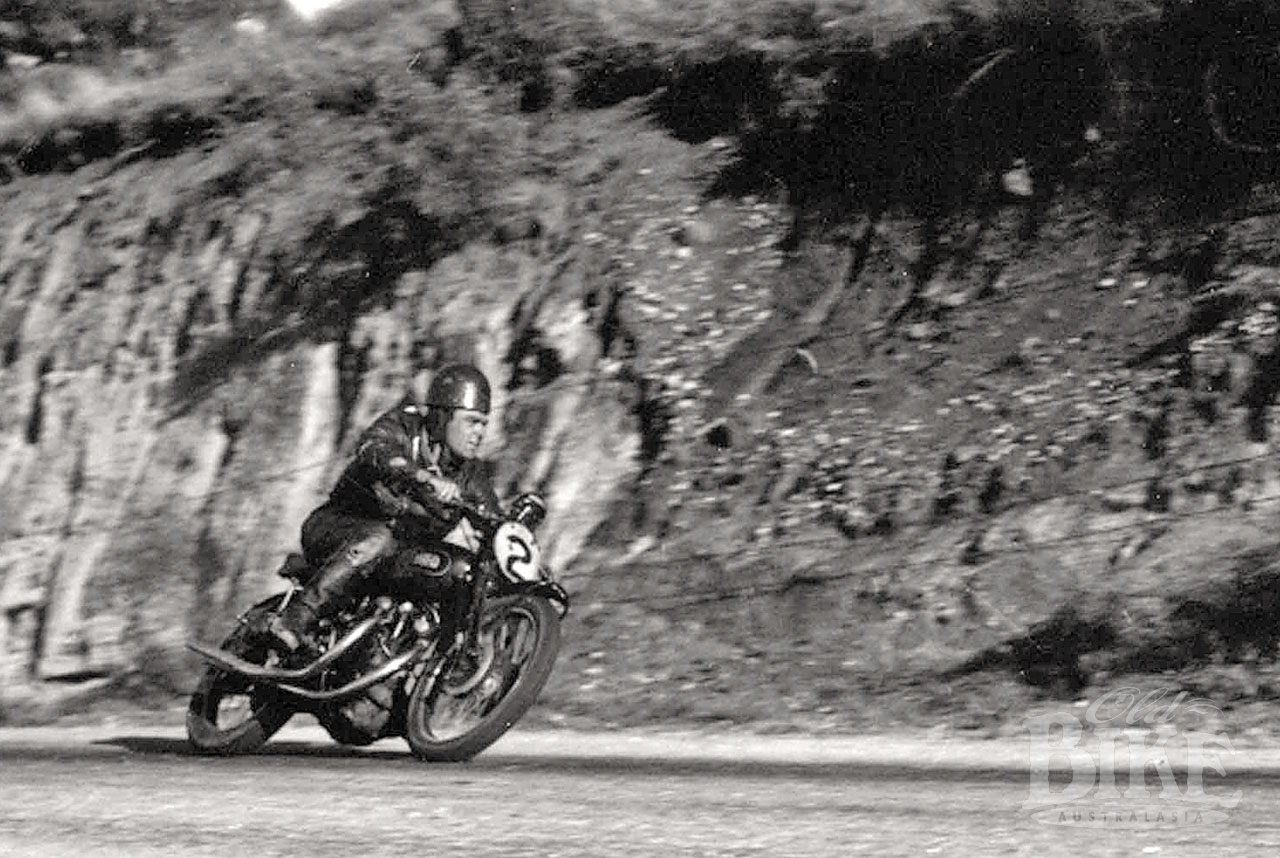

McAlpine’s Gilera arrived on the Isle of Man by ship from Genoa only days before official practice started. The Sanremo had proved a nimble device around the small Italian tracks, with good acceleration and reasonable handling, but on the super-high gearing necessary for the 60 kilometre TT lap, it was not nearly so impressive. On his 350cc AJS 7R, McAlpine set quicker lap times than on the 500cc Gilera, the main problem being not so much that of outright speed but of lively handling from the distinctly pre-war chassis. In the 7-lap Junior TT, Tony brought the AJS home in an excellent 13th place at an average of 134.8 km/h, good enough to earn one of the prized First Class Replica trophies. In the Senior, held five days later, the Gilera broke a valve spring soon after the start and he struggled around the lap before retiring at the pits.

For the rest of the year, Tony raced in Britain and on the Continent before sailing for home, bringing with him the Gilera and the Vincent Black Lightning that he had helped to build at the Vincent factory. The Lightning found a new owner, Jack Forrest, but the Gilera took longer to sell and was left with Sydney dealers Burling & Simmonds. For the 1952 European season, Tony decided to go with the flow and ordered a pair of Manx Nortons, a 350 and a 500. At the Isle of Man he again put in a sensational performance, finishing 13th in the Senior at an average of 137.47km/h. The dozen riders ahead of him were all mounted on works or works-supported machines. There was no joy in the Junior, with engine trouble putting him out, but the Australian flag was well and truly upheld by Tony’s mate from Sydney, Ernie Ring, who took a sensational eighth place in his TT debut.

A seventh place in the Senior German GP took Tony tantalisingly close to scoring a world championship point, but it was the non-title international events that brought the money in. The Nortons went back to Australia at the season’s end to help satisfy a market hungry for racing tackle, and a new pair was ordered for 1953. The TT brought only modest results, but the Belgian GP a few weeks later was a black day. 35-year-old Ernie Ring’s performances had gained him a spot in the works AJS team. In the 500cc Belgian GP, Ring made his debut on the twin-cylinder AJS ‘Porcupine’ and spent most of the race dicing with McAlpine. On one of the flat-out bends on the 13-kilometre circuit in the Ardenne Mountains, Ring lost control and speared off into the pine trees. McAlpine, who witnessed the crash, stopped at the nearest ambulance point to alert medical staff, but it was too late for Ring. As usual, Tony concentrated on the non-championship races, but in September scored that world championship point with sixth place in the Italian 350cc Grand Prix at Monza. Perhaps his finest performance to date came at the terrifying Freiburg Hill Climb in Germany – a 13 kilometre climb with 177 corners that rises 1,000 metres. On his 500cc Manx Norton, Tony came within two seconds of winning the event and provided the 100,000 fans with a glimpse of his pre-war style as he slid the Norton through the gravel-strewn corners.

One strike and you’re out

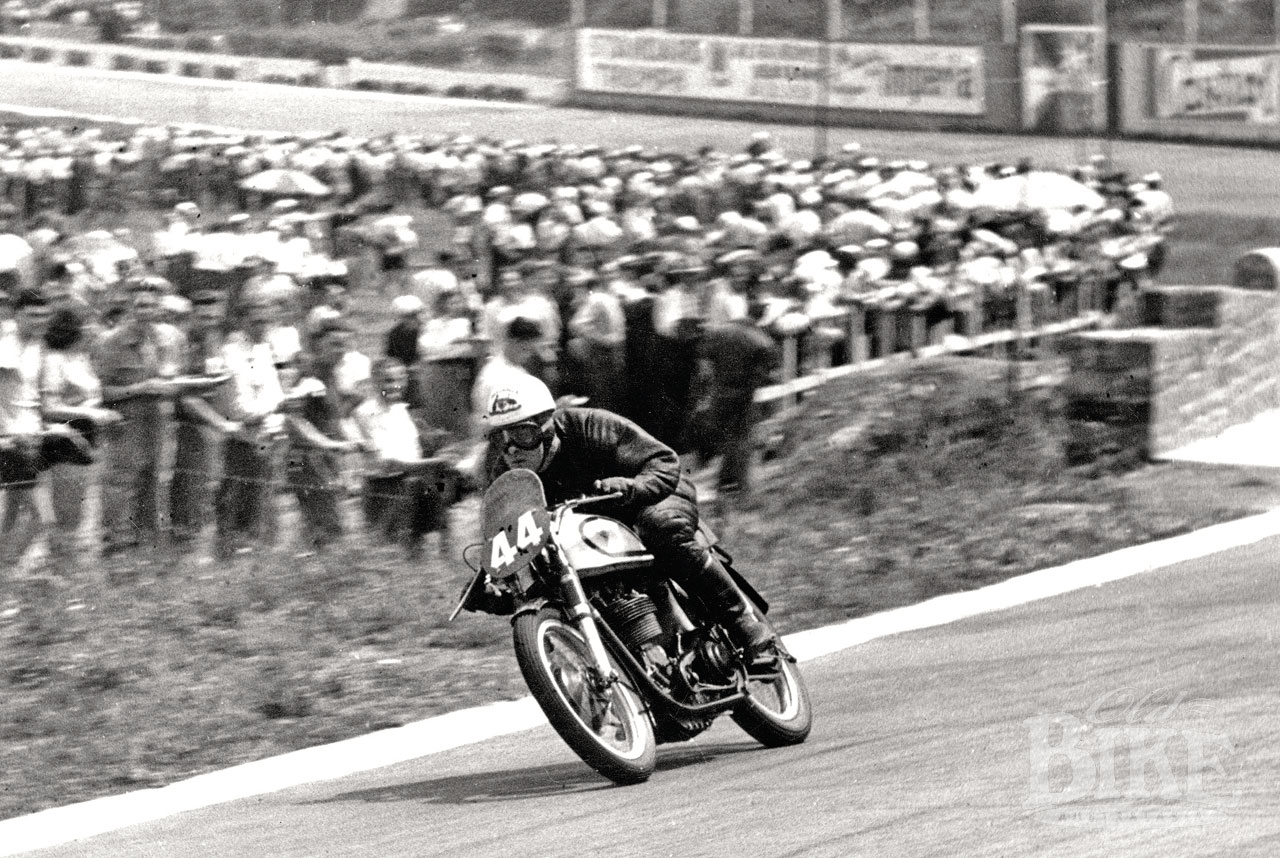

It was a good life, and one that suited the McAlpines. Tony had learned how to ride quickly enough to always be on the promoter’s shopping list for well-paid international meetings in Belgium, Italy and Germany, and how to conserve the precious machinery. For the 1955 season, Tony had managed to acquire one of the rare and expensive 500cc BMW Rennsport racers, and was looking forward to a lucrative season. His reputation for clashing with officialdom gained another chapter after he decided to buy a supply of US war surplus helicopter pilots’ helmets, which Tony (probably correctly) reasoned to be safer than the universally worn Cromwell ‘pudding basin’ style. Faced with refusal to be allowed to start in some early season German meetings in his new headwear, McAlpine threatened to sue the organisers who quickly backed down. His ‘jet’ style helmet was certainly conspicuous.

Then in July 1955 came the incident that finished his motorcycle racing career. There had long been dissatisfaction at the Dutch TT over the paltry starting money offered to the privateer riders who made up the bulk of the grid at an event that regularly attracted over 100,000 paying spectators. The riders concerned petitioned the organisers for a better deal, which was flatly rejected. In the 350cc race, the majority of the field completed just one lap and retired at the pits, leaving the organisers outraged. The Dutch federation took the matter to the highest court resulting in most of the dissidents, including McAlpine and fellow Australians Jack Ahearn, Bob Brown and Keith Campbell, and New Zealanders John Hempleman, Peter Murphy and Charlie Stormont, having their licences suspended for six months from January 1st 1956. It was a major blow to McAlpine, who had somehow managed to buy a works 500cc Rennsport BMW for the 1956 season.

The rare and expensive German racer was shipped back to Australia, where McAlpine entered it at Bathurst at Easter 1956 for Jack Forrest to ride. Forrest had an option to buy the bike, which he duly exercised after sweeping to victory in the Senior TT, despite riding with a broken ankle sustained after he hit a hare in the earlier 250cc race.

Tony had talked of resuming racing once his licence suspension had been served, but it didn’t happen. Instead he moved to Katoomba in the Blue Mountains where he opened a wood, coal and coke Fuel Yard, and shortly after, a quarry at nearby Wentworth Falls. This led to an expansion into the earthmoving business after landing a contract for the construction of the huge Power Station at Wallerawang near Lithgow. Over the next twenty years, Tony McAlpine became a very wealthy man with numerous property deals, and a motel in Quirindi in northern NSW. In the 1980s the McAlpines moved back to their original stamping grounds near Camden, where Tony installed an airstrip for his private plane. When Vivian died in 1988, he moved to Runaway Bay on Queensland’s Gold Coast and remarried in 2000.

It’s true that Tony McAlpine wasn’t the easiest bloke to get along with. Gruff, forthright and incredibly strong-willed, he could be hard work. But for a time, there wasn’t a motorcycle rider in this country that could stay with him. His motor sport career included not just bikes, but several car racing exploits (including the fabled Mount Druitt 24 Hour Race in an MG), speedboat racing and even aircraft racing. He loved flying, but said that he found car racing “palling compared to bikes”. On the race track and in life, they didn’t come any tougher than Tony.