Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photographs Frank Shepherd, Bill Tricker, Charles Rice • Archival assistance: John Wicks

Even though it closed almost fifty years ago, Mount Druitt is inevitably mentioned whenever a bunch of old timers get together to talk motorcycles. In the bleak days that followed World War 2, ‘Druitt’ was a breath of fresh air – a proper, permanent, tar-sealed racing circuit close to Sydney, not a dirt track or a collection of public roads sealed off for a weekend’s sport.

The war had been a long, bitter, drawn-out experience but it produced one tangible benefit in that all around the country, airstrips, some abandoned, some operational and others retained purely for emergency use, lay basically unused. Although far from ideal in that any motor sport use was limited to what configuration was presented by the runways, the strips were at least numerous. Around Sydney, the airstrips at Castlereagh, Schofields and Marsden Park all saw some form of motorised action, as did Mount Druitt. Located on the northern side of the railway line to Penrith, near Ropes Creek, the strip was roughly tar-sealed, about 1.5 kilometres long and about 100 metres wide. As early as 1948, cars and motorcycles raced on a simple “flattened oval” consisting of two hairpin corners around empty fuel drums spaced around 1200 metres apart. As basic as this layout was, the motor sport-starved public lapped it up, with crowds of up to 15,000 people flocking to the venue, thanks to its easy accessibility. The main train line brought spectators to Mount Druitt station and from there it was about 30 minutes walk through the paddocks to the airstrip at the bottom of the hill. The Great Western Highway, running parallel to the rail line, delivered vehicular traffic to the site via a dusty and narrow side road which inevitably choked with traffic every race day.

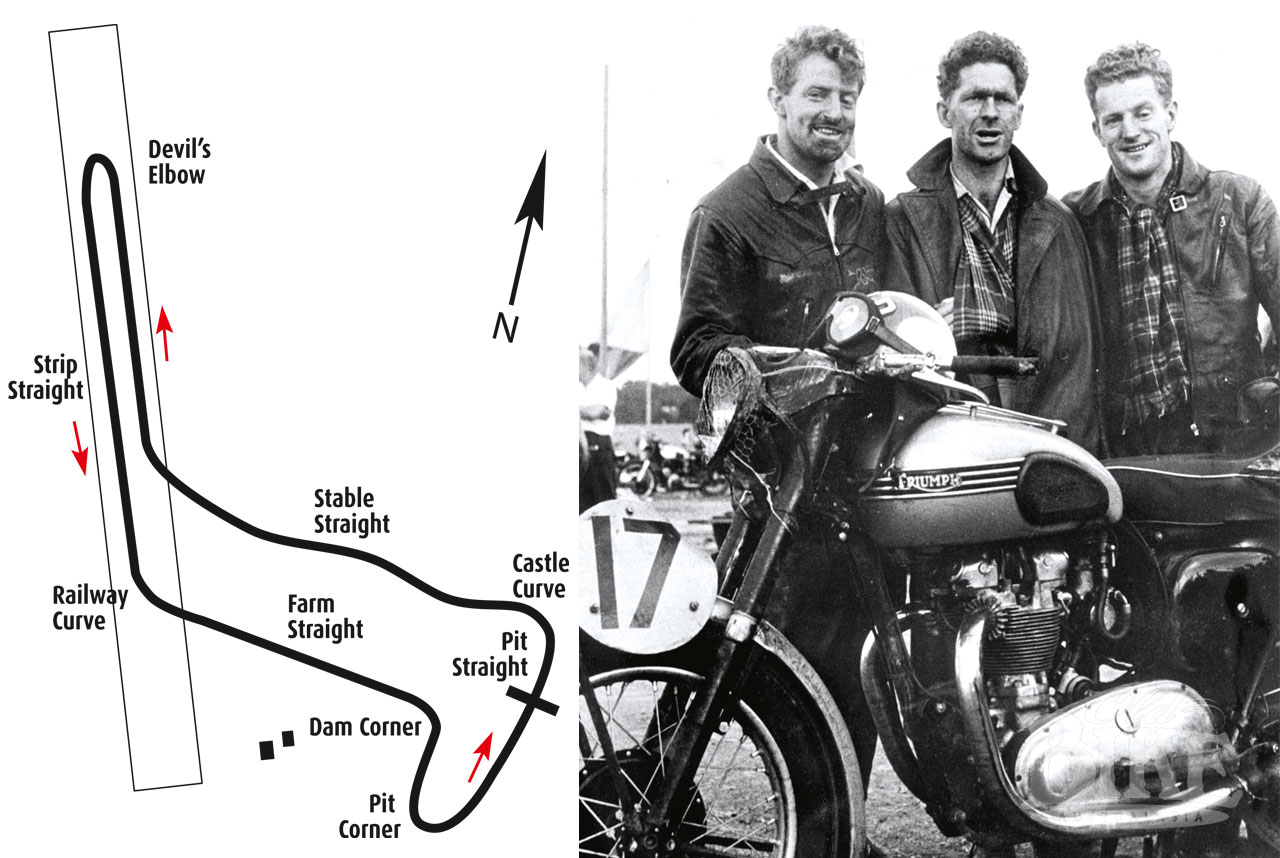

For three years the airstrip races ran regularly, but by 1952 plans were well advanced to dramatically transform the facility by tar-sealing a series of access tracks that ran down the hill through the scrub and long grass to both ends of the strip. To link these tracks, a new section of bitumen was laid, and this became pit straight. The result was an anti-clockwise 3.6 km circuit that, due to its changes in elevation provided excellent viewing. From the starting line on top of the hill, the first, sweeping left hand corner dropped sharply through a slight right/left kink to a very fast double right hand corner that led onto the airstrip. 200 metres later the track did a U-turn and ran back down the strip, before another very quick left hander sent competitors back up the hill to a sharp adverse-camber right hander around a dam. Then followed a looping left leading back onto pit straight. The property was leased to a colourful character named Belf Jones, a part-time car racer, showman, entrepreneur, you-name-it sort of fellow. Car races were conducted by the Australian Racing Drivers Club, and motorcycle events by various clubs such as The Motor Cycle Racing Club, Willoughby DMCC, and by the Auto Cycle Union itself.

Open for business

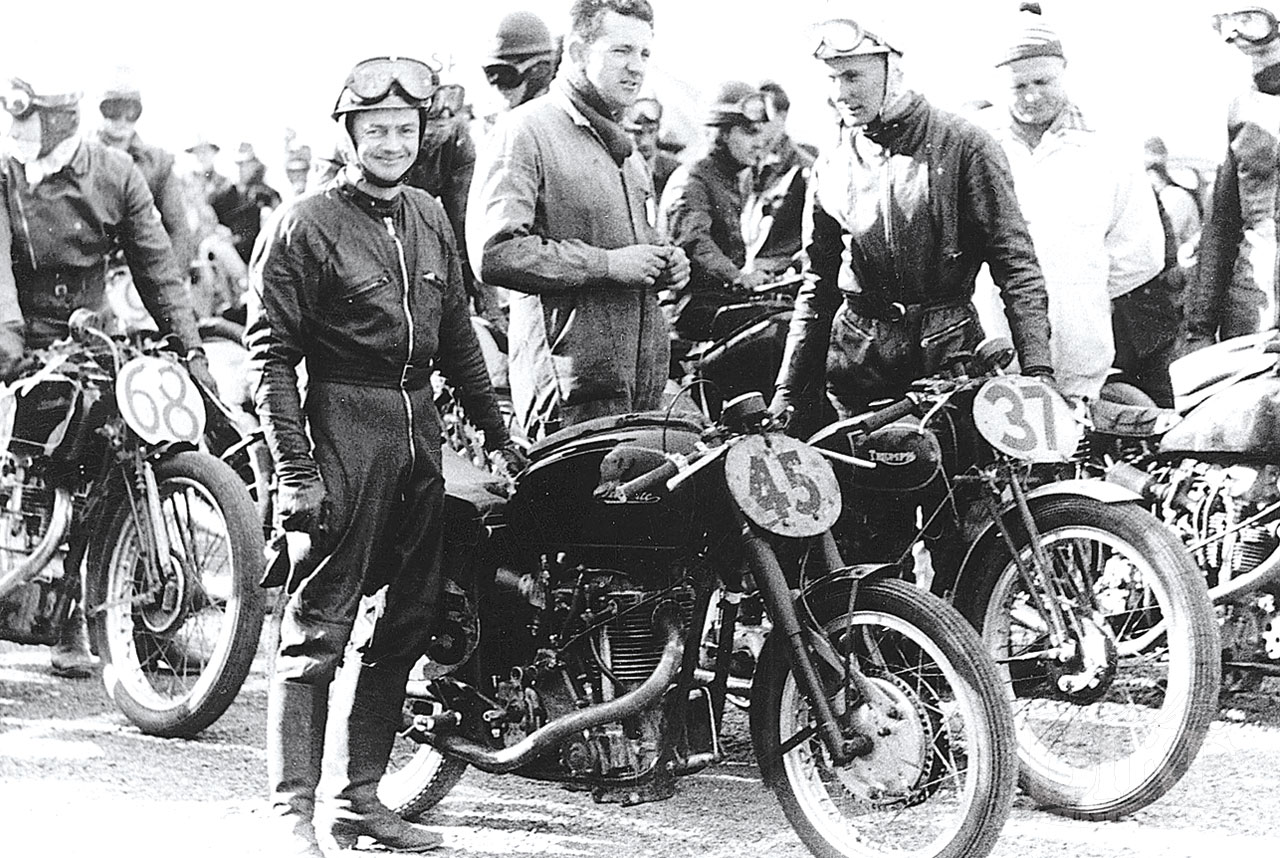

The opening meeting on the ‘new’ circuit was supposed to be May 11, 1952, but the road surfacing had not been completed due to prolonged wet weather, so a makeshift lap using the airstrip and some unsealed roads was used. Six more months were to pass before the bikes had a crack at the fully-sealed circuit, on November 16, 1952. The meeting was an enormous success, spectators standing “three-deep around virtually the entire lap”. Star of the show was young Alan Boyle, mounted on a KTT Velocette. He won the 350cc and Unlimited events, and placed second to Bob Brown in the Senior. On his six-speed BSA Bantam, Wollongong rider Bill Morris won the 125cc race and Sid Willis took out the 250. The motorcycle meeting actually preceded the first car races by two weeks, and drew a considerably large crowd. At the car meet, motorcycle champion Lloyd Hirst, who had taken to four wheels with an 1100cc Cooper JAP, set the outright lap record at 1 minute 46 seconds.

It was the beginning of a happy association for bikes at Mount Druitt. The circuit was far from perfect, being rather narrow and prone to breaking up, amenities were almost non-existent and there was little shelter, but it could but it was fast and flowing, handy to Sydney, and extremely popular with riders and spectators alike.

Racing continued on a regular basis in 1953, but on Anniversary Weekend (January 31 and February 1), the bikes played a supporting role to the much-vaunted 24 Hour Race for Production Cars. Luckily, the motorcycles ran on the Saturday, because after the round-the-clock pounding dished out by the cars, there was little of the circuit left. Three days of heavy rain prior to the meeting turned the pits and spectator areas into a quagmire, and left the already-flimsy track surface poorly equipped to handle the pounding. It took many months to put the surface into useable order again, the numerous potholes being refilled by hand rather than complete resurfacing. The race itself has gone down in the annals of Australian motor racing as a disaster, poorly run and surrounded by seemingly interminable controversy. Not surprisingly, the car race was never repeated, however not one but two, equally chaotic 24 hour motorcycle races subsequently took place.

The first of these (officially titled The 24-Hour Motor Cycle Reliability Speed Test for Stock Machines) was held on the weekend of October 3&4, 1954, after the track had been largely re-skinned. 32 entries were received for the various solo and sidecar classes, which ran together. The glamour entry came from the trio of the country’s hero Harry Hinton and his two sons Harry Junior and Eric on a 500cc Featherbed Norton International, and they duly controlled the race until a re-fuelling stop at 8pm on Saturday night. Petrol found its way onto the battery and the fuel tank exploded, briefly lighting up the pit area which only had a few hurricane lamps scattered around for illumination. Further chaos ensued soon after, when cattle wandered onto the dark lower reaches of the circuit. Several riders stuck a cow and more went down in the confusion, but the race went on until 3pm on Sunday afternoon. The 600cc BMW team of Jack Forrest, Len Roberts and Don Flynn took the win with 648 laps completed, ahead of a 650 Triumph ridden by Keith Bryen, Barry Hodgkinson and Bill Tuckwell, 19 laps astern. Sidecar winner was Bruce Rands’ 500 Norton.

It may have appeared mismanaged from the outside, but officials, the ACU and the co-promoter, Belf Jones’ Speed Promotions, were sufficiently enthused by the event to schedule a second running one year later, October 29 & 30, 1955.

Star billing

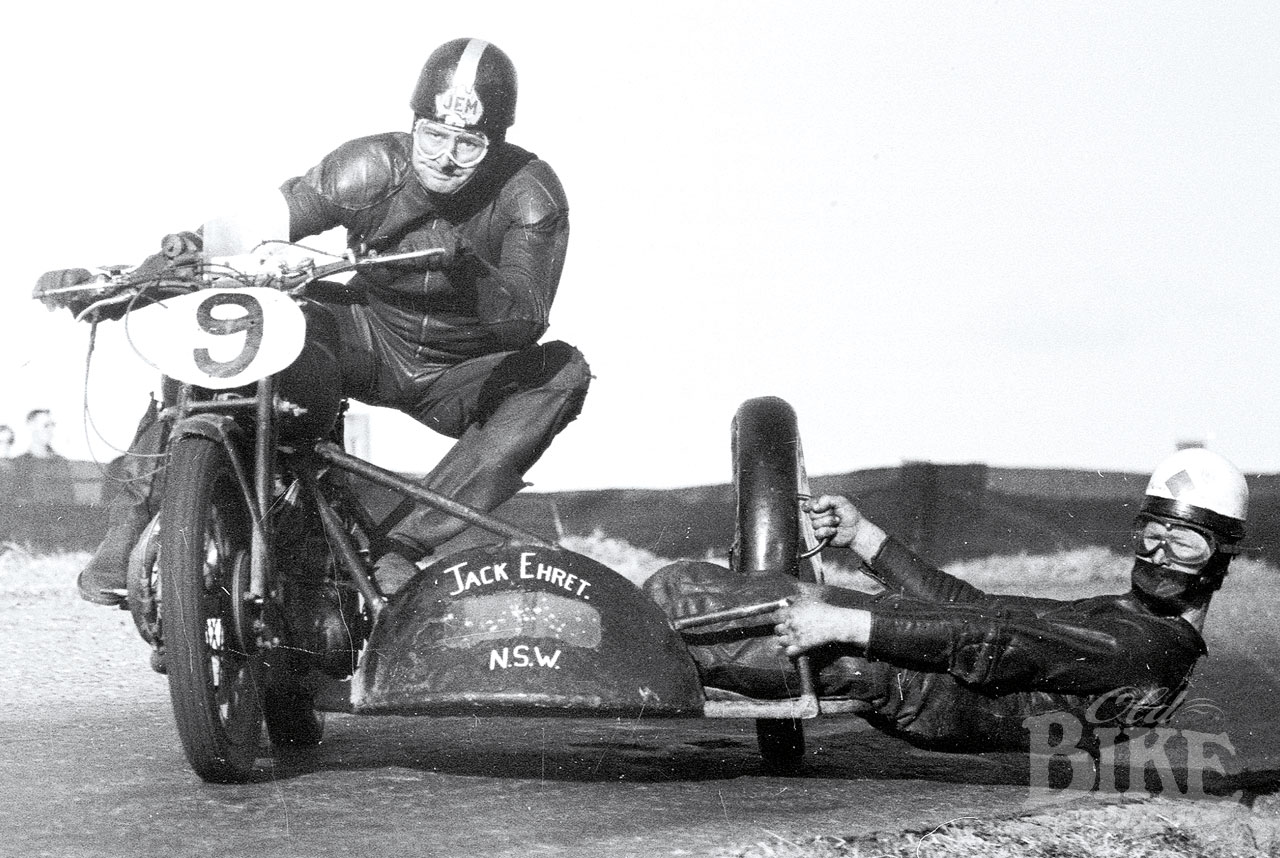

Before this however, came the most successful event in the circuit’s history, at least in motorcycle terms. World Champion Geoff Duke O.B.E., the charismatic Englishman who had put motorcycle racing on the world map via his title wins for Norton and Gilera, arrived for the NSW leg of his tour in February 1955. The Blue Mountains Grand Prix drew all the top local names to challenge the champ; Maurie Quincey, Harry Hinton Senior and Eric Hinton, Bob Brown, Keith Stewart and Jack Ehret, but the fire-engine red Gilera in the hands of the maestro was untouchable. Ehret, on his ex- Tony McAlpine Vincent Black Lightning, enjoyed a moment of glory in the Unlimited GP when he briefly led Duke, but once into his stride the stylish Lancastrian won as he liked. The big time had come to Mount Druitt. Ten thousand spectators trudged their way back through the tinder-dry summer grasslands, happy in the knowledge that they had seen a true superstar in action.

Life returned to normal for the circuit, until the time came to get organised for the second running of the 24 Hour race. The motorcycle trade, reeling under the onslaught of cheap cars and the broad brush of social unacceptability, rallied around the event with unprecedented support. Distributor-backed teams came from Triumph, BMW, Matchless, BSA and Velocette in the quest for outright honours, while the 250cc class had a distinctly Teutonic flavour with entries from NSU, BMW, Adler and Puch. Jack Forrest returned from Europe with a new R69 BMW, while the Hintons had a new Norton International to replace the incinerated model.

The meeting took place only three weeks after the opening of the electrified rail line to Mount Druitt, greatly increasing the accessibility for spectators coming from Sydney. However before the race weekend itself, things went badly wrong during a mid-week night practice session when a horse strayed onto the circuit and was rammed a high speed by Len Roberts’ 600 BMW. Roberts died soon afterwards and both the Tom Byrne supported BMW and Adler teams withdrew, leaving 38 solos (there was no sidecar class) to face the starter.

Once again the Hinton Norton made the running until the primary chain snapped and jammed the transmission, throwing Eric off and inflicting a broken arm. Just after midnight, tragedy struck again when Don Blackburn crashed heavily on the run down the hill. In the pitch black, many others ploughed into the wreckage and the race was stopped for one hour. Blackburn died on the way to hospital but miraculously there were few other injuries. With half the distance still to run, the race recommenced and ultimately went to the private team of Canberra brothers Barry and Don Sluce, and Bruce Woodyatt on a 500cc Triumph Tiger 100. But the 24 race was doomed. Fearful of a catastrophe, the ACU demanded much more stringent safety measures for both riders and spectators which were beyond the scope of the promoters. The motorcycle trade was also in the grip of plummeting sales and showed little interest in the staging of a third event.

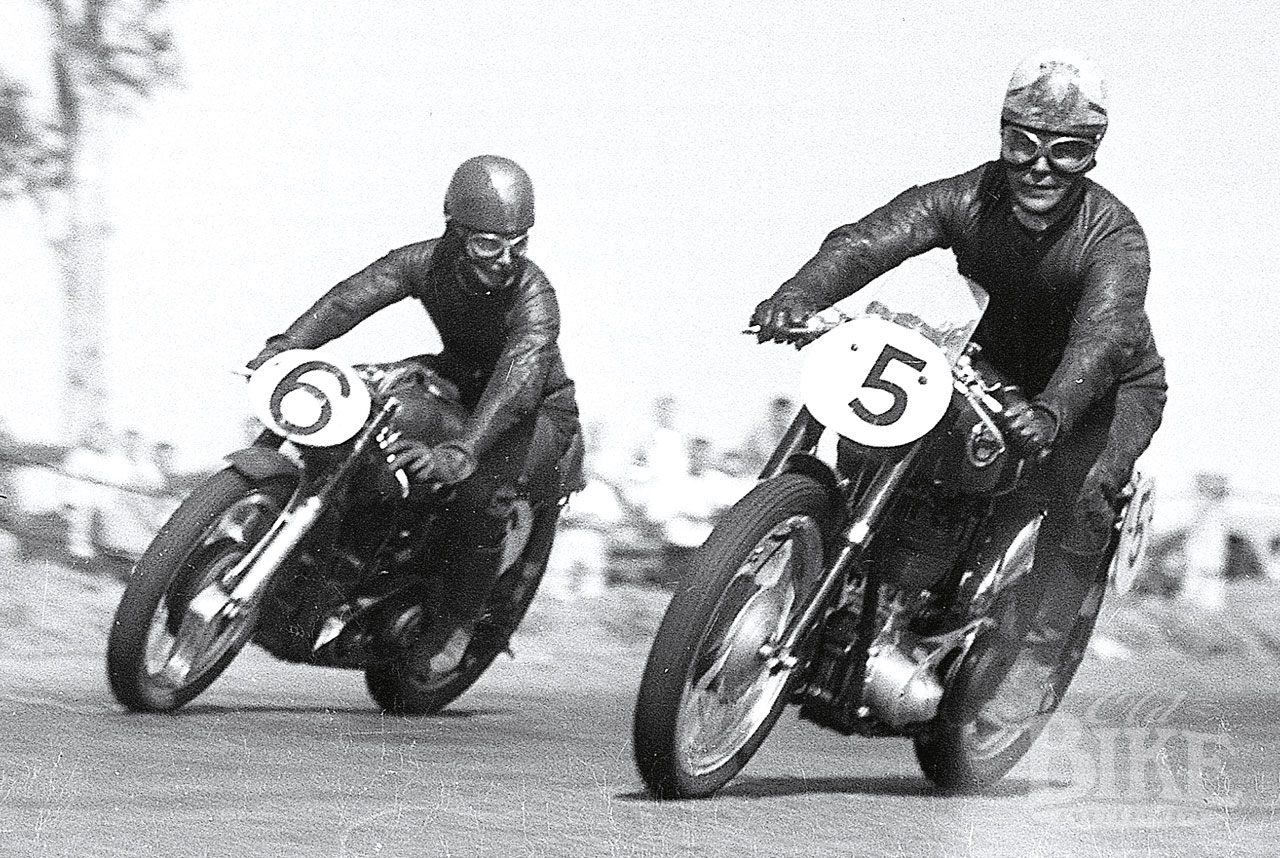

Life returned to normal at Mount Druitt, which hosted a meeting virtually every month for either cars or bikes, with a steady stream of interstate stars hoping to challenge the home-track heroes. The first big date for 1956 was February 5, when the touring works Moto Guzzi duo of Bill Lomas and Dickie Dale arrived. As expected Lomas controlled the 350 race until a cloudburst flooded the circuit, and the Guzzi’s ignition, letting Keith Conley, aboard Dick Thompson’s AJS 7R through to inflicted a famous defeat on the Italian team. Dale upheld Guzzi’s prestige to win the 500. Later in the year at the NSW TT, held on September 16, Jack Ahearn, took a 350/500/Unlimited triple win on his Nortons. In June the following year, Ahearn repeated the feat, while in the sidecar ranks, the locals were soundly trounced by returning Victorian international Bob Mitchell, who had finished fourth in the 1956 World Sidecar Championship. A season closing ‘International Grand Prix’ took place in December 1957, where rising star Tom Phillis defeated Harry Hinton Junior and Ahearn to win the feature Senior GP. Earlier, Hinton (NSU) had won the 250 race and Bob Brown (AJS) the 350.

Things were sailing along nicely for the circuit, but there was a double crisis looming. The ARDC had been at loggerheads with Belf Jones for years over the promotional rights for the car races, and on more than one occasion had announced that it had gained the upper hand, only for Jones to bounce back victorious. But with Jones’ lease due to expire at the end of 1958, the ARDC sealed the matter by announcing that it would henceforth become the sole promoter. An even bigger issue concerned the impending NSW Speedway Control Bill. This forced every speed-event circuit in NSW to be licensed and to conform to strict safety standards dictated by the state Police Force, and affected everything from dirt short circuits and scrambles tracks to high-speed road racing venues. The bill was due to come into force by mid-1958 and for this reason Mount Druitt’s now-customary NSW TT was shuffled forward to March 1958, just before the annual Bathurst meeting. Star Victorian all-rounder Ken Rumble caused a major upset when he defeated young Kel Carruthers and Eric Hinton to win the Junior, and also took out the 250 race on Les Diener’s DOHC Velocette, beating perennial Druitt Lightweight winner Sid Willis. Hinton had his revenge with a 500/Unlimited double, while dirt track star Roy East took out the 125cc GP on Clem Daniels’ MV Agusta. The Speedway Bill was still on hold but definitely looming as the year drew towards a close, and it was obvious that Mount Druitt could not comply without major work, something the ARDC had publicly committed to should they be successful in securing the lease.

Over and out

On Sunday November 16, what transpired to be the final race meeting of any kind at Mount Druitt took place – an open meeting conducted by MCRC. The late season date meant Eric Hinton and Bob Brown were home from Europe, and Eric started his day by winning the Lightweight on his trusty NSU over Ray Curtis on Nooge Smith’s highly developed New Imperial. On his 350 Norton, Hinton battled hard for the entire Junior race with Brown on Elmer McCabe’s 7R AJS. Brown gained the verdict narrowly, with Carruthers third ahead of one-eyed veteran Len Deaton. In the Senior the same pair made the running, with Hinton this time victorious and Victorian Frank Spiller, on his home-brewed Triumph, a commendable third after a high-speed practice crash. There was a major upset in the 750cc Sidecar race when Inverell rider Gordon Turner on his self-built 650 Triumph caught and passed favourite Orrie Salter on the ex-Bob Mitchell Manx Norton outfit. The field for the Senior Sidecar was identical except for the colourful Jack Ehret on his Vincent Black Lightning and he duly led the field a merry chase. But coming through like a rocket was Turner, who once again disposed of Salter and set off after the Vincent, running out of laps but finishing a gallant second. The very last race run at Mount Druitt was the Senior C Grade Final, won in fine style by Keo Madden (who had earlier won the Junior B) from Stan Bayliss and Graham Tulk.

It had been another typical Druitt day – great racing in a friendly and relaxed atmosphere, and there were high hopes that the twin issues of the lease and the Speedway Bill could be resolved in time for the 1959 season to go ahead as planned. The issue was put beyond doubt just one week later when Belf Jones, incensed at the granting of the lease to ARDC, climbed in a tractor with a ripper attached at the rear and drove around the entire circuit, gouging a zig-zag trench through the surface. Jones was charged with malicious damage but after nearly two years of legal action, was acquitted. For Mount Druitt, motor racing was finished, with the ARDC unable to raise the considerable finance necessary to resurface the track and erect the fencing to comply with the Speedways Bill.

Regardless of this contretemps, the track’s days were undoubtedly numbered. Sydney’s western suburban sprawl was sweeping across the plains and had arrived at Mount Druitt’s doorstep. Within a few years the circuit would become the suburb of Whalan. Today, there is virtually no reminder of the track’s existence. Playing fields have been built on the former airstrip. Madang Avenue runs across what was the downhill section, while the lower reaches of Morseby Drive almost touches the beginning of the fast right hander onto the strip itself. But ask anyone who went to ‘Druitt’- and there were many thousands, – and you’ll be told that the place was special. Certainly, the track had its stars; Bob Brown, Sid Willis, the Hintons, and Jack Ahearn, but more importantly for the sport, it provided a platform for the up and comers. Future world champions Tom Phillis and Kel Carruthers, and the clubmen racers – such as Ross Pentecost, Roy East and John Shanks – who made up the bulk of the grids. Even in the depths of winter or a scorching western suburbs summer day, ‘Druitt’ was always a good place to be, regardless of which side of the fence you were on.

Little left

There’s not much remaining of Mt Druitt, the circuit – houses, factories and warehouses now occupy the site. It takes a fairly good memory or a vivid imagination to visualise just where the circuit was, but it can be done. Off Debrincat Avenue, the old airstrip is still there, sort of. A section of tarmac on the site of the old strip leads to playing fields, and to your left are grassy paddocks with the sprawling suburb of Mount Druitt up the hill. If you journey around to the other side and drive down Samarai Road, a small park lies on the lower side, almost opposite Mendi Place. This is close to the old downhill Esses, and a small patch of tar is still visible in the grass to the right of the reserve. Kurrajong Street finishes in a cul de sac, and a short stroll from here, under the powerlines, is what used to be Dam Corner. Amongst the rubble on the site of the old dam are bits of bitumen, presumably bulldozed into a heap when the walkway and cycle track were constructed on what was the infield of the circuit.

A lap of Mount Druitt with John Shanks

Milton ‘Johnny’ Shanks was synonymous with Ariels during his relatively short racing career, which finished with the final Mount Druitt meeting in 1958. In Easter of that year at Bathurst, Shanks had his pushrod Ariel in third place, behind the Nortons of Eric Hinton and Ron Miles, for the majority of the Senior TT but was just pipped on the final lap by George Colley’s Matchless G45. By his own admission, John found himself gazing at the mountain scenery instead of concentrating on the job at hand, dropping his lap times by as much as 11 seconds. It was time to give it away.

“The starting area at Mt Druitt was fairly flat but the road began to drop away just before the first corner (Castle Curve – named after the abandoned mansion on the outside of the corner). There were pine trees on the inside so you couldn’t see through he corner, which was first gear on a close-ratio four-speed gearbox. Then you’d wind it up all the way down the hill, through the esses, which could be taken flat out. We were ready to put it in into top just before the right hander onto the airstrip – good blokes like Jack Ahearn would go through there flat out. I used to run a speedo on the Ariel which was fairly accurate, and it was showing 108 or 109 (mph) just before we’d brake for the drum (Devil’s Elbow). We’d stay in close around the drum – there was no point going out wide because it was just extra distance – then it was hard acceleration up to third for the corner off the airstrip (Railway Corner). I came off there in the wet on my VCH (Ariel) when the back tyre let go, and I can still see the spectators on the outside of the corner running in all directions – it was a quick corner.

Anyway, we’d come off the airstrip in third, driving hard up the hill towards Dam Corner and get into top briefly before braking hard because it was a tight corner, probably second gear, then low gear for the one onto the straight (Pit Corner). This was a cutting, with a high bank on the inside. The surface wasn’t too bad, except for the bit at the bottom of the hill – this was rough enough to put dents into alloy rims. This was the area of the bad accidents in the 24 Hour Races (when the cow and horses strayed onto the circuit). The fences weren’t in good condition. There wasn’t much in the way of amenities at Mount Druitt. There was one water tap at the bottom of the pits and I think one on the outside of the circuit where the officials’ car park was located. At the Geoff Duke meeting (in 1955) it was incredibly hot and there was no shade, no water, really unpleasant.”