Story: Dennis Quinlan and Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Dennis Quinlan archives.

Could the Velocette Model O have saved the company? It had everything going for it, but the timing wasn’t especially good.

When Velocette decided to join the rush to produce a parallel twin, it did so with typically unconventional thinking. The boffins at Velo, namely Harold Willis and Charles Udall, envisaged not just a road machine, but a design that could hold its own on the race tracks. While this pair pondered the competition side of the equation, it was our own Phil Irving who was charged with the task of turning the road version into metal, which he apparently did quite separately from the efforts of the Velocette race department.

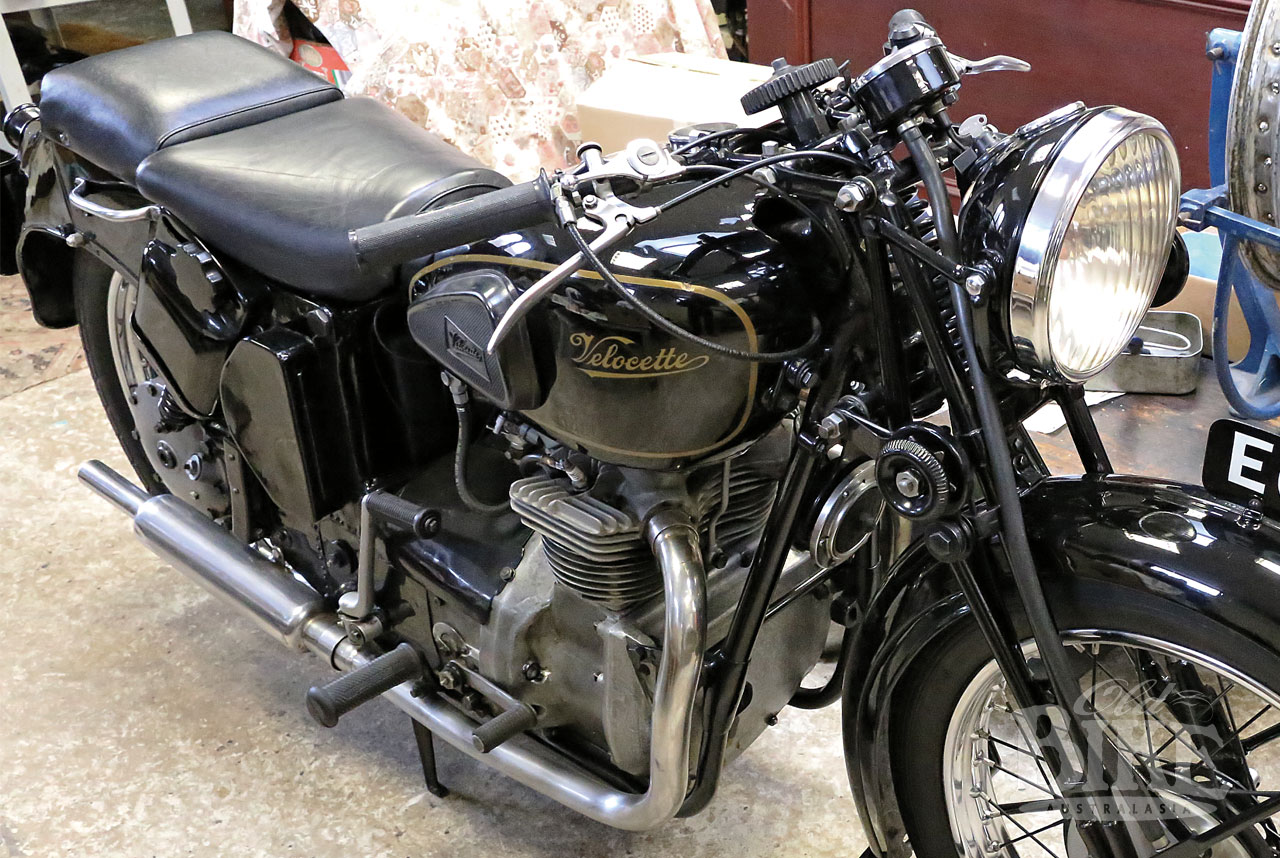

Irving’s creation, which was officially known as the Model O, was similar in many respects to the fabled Roarer, the supercharged 500 which had a solitary appearance in practice for the Isle of Man TT in 1939 where it was ridden by Stanley Woods. The Model O, which following the basic layout of the Roarer, differed in that it had pushrod-operated valve gear instead of overhead camshafts, and a dynamo to power the coil ignition.

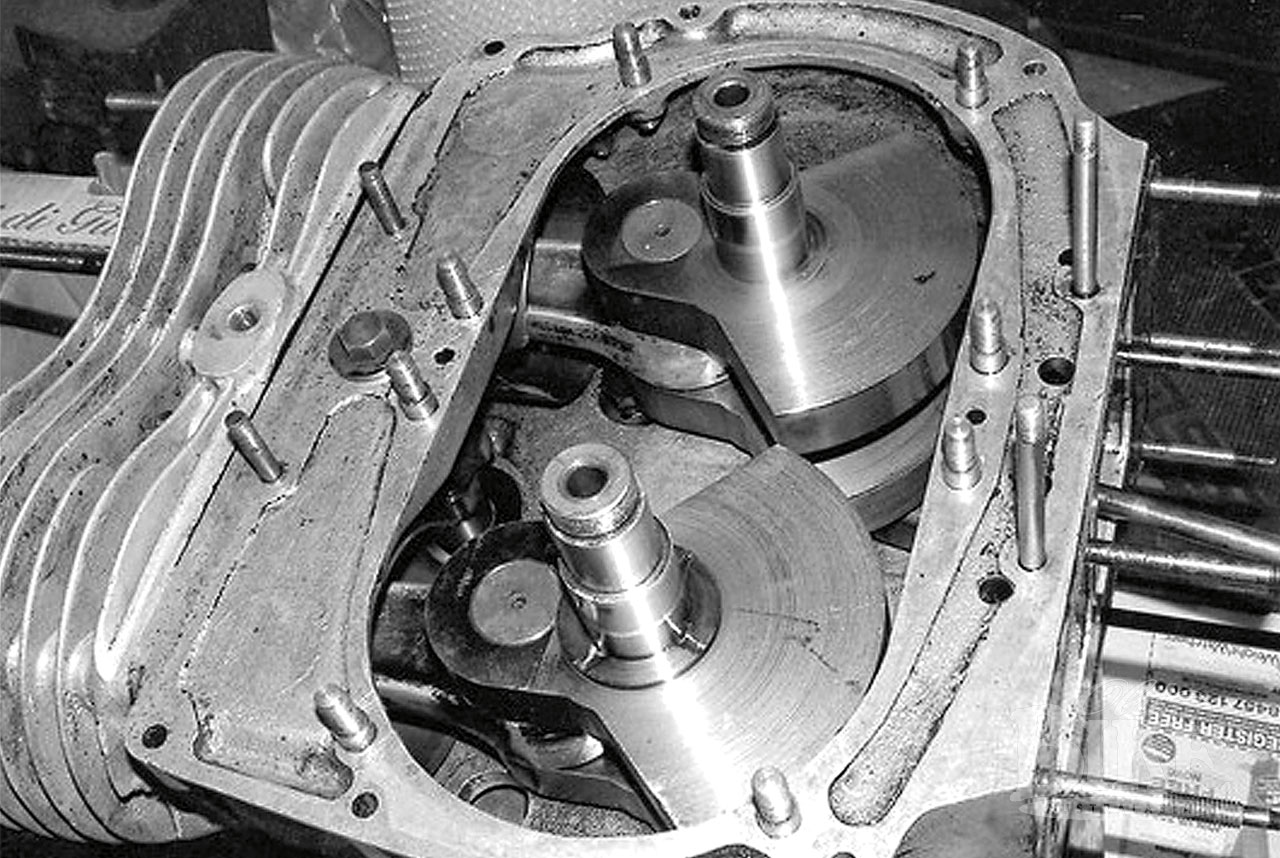

Irving’s design used a pair of contra-rotating crankshafts which were geared together, running fore and aft in the frame, not crossways. The advantage of this arrangement, Irving claimed, was that “excellent primary balance can be obtained by counterweighting each shaft to a balance factor of 100 per cent, the unwanted centrifugal forces existing at mid-stroke neatly cancelling each other out.” Either crankshaft could then be used to transmit the power to the transmission, with shaft drive to the rear wheel, thus eliminating either primary or final drive chains completely.

The Model O engine was originally to use the same bore and stroke as the much-loved MOV, 68.0 x 68.25mm, to give 496cc in twin cylinder form, but in prototype form, 74mm pistons from the OHC KSS engine were used with the same stroke, giving 588cc. The cylinder block, cast in iron, was wide enough to accommodate the crankshafts, which needed to be just over 5 inches apart to give clearance for the crank webs. These webs were cut from steel plate and surface ground parallel, fitted with hardened mainshafts and crankpins with hardened sleeves. Con rods were made from RR56 aluminium alloy, and ran directly onto the gudgeon pins and crankpin sleeves. The barrel shaped crankcase was cast in aluminium, with an elongated opening at the front to allow the cranks to be inserted, these running in plain main bearings at the rear housed in the crankcase itself, while the mainshafts ran in a cover secured to the front wall of the crankcase. The camshaft, driven by a duplex chain, was located between the cylinder barrels and tensioned with an adjustable ‘slipper’. To give extra crank mass, both cranks carried additional ‘flywheels’, and one crankshaft carried the clutch which drove to a directly-coupled gearbox.

The cylinder head was a single casting in Y-alloy with the rocker boxes cast integrally. Careful attention was made to airflow between the head and the cylinder barrels. Much of the top end, including the valve springs, guides, and valve seat inserts came from the KSS, with very short steel capped aluminium pushrods. Wet sump lubrication, with a sump bolted to the crankcase, delivered lubricant from a gear-type pump. Twin Amal Type 6 carburettors drawing from a single bowl were fitted, although Irving felt that a single carburettor would have sufficed.

Many of the gearbox components were sourced from MOV parts, running at engine speed instead of half speed on the 250 single. Even though they would have to transmit around twice the power of the 250, they were considered to be strong enough for the job. Arranging the kick starter was a complex job, and so it could operate in the conventional pattern and not transversely, it had to be mounted on a cross-shaft and supported externally. This was always a less-than-satisfactory arrangement and no doubt would have been re-thought had the model ever reached the stage of production.

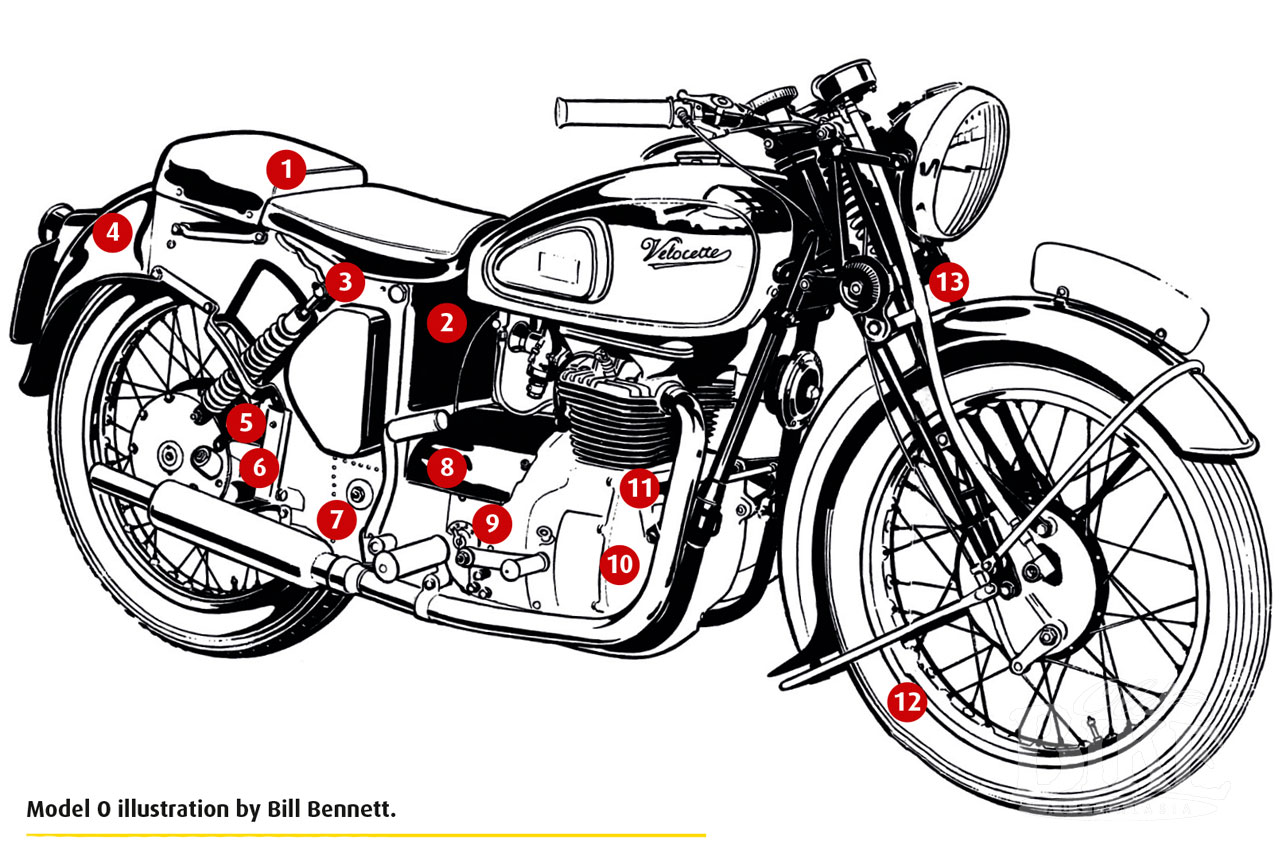

To reduce the transfer of any vibrations to the rider via the handlebars, the whole engine was rubber mounted (probably the first to do so on a motorcycle) using a new process called Metalastic, although it was mounted at only three points and thus could not be considered to be a stressed member. It was impossible to work on the engine internals without removing the unit from the frame, so the extraction process was made as simple as possible. This involved easily removable front engine mount brackets, with a clamp beneath the gearbox attached to the rear frame cross member.

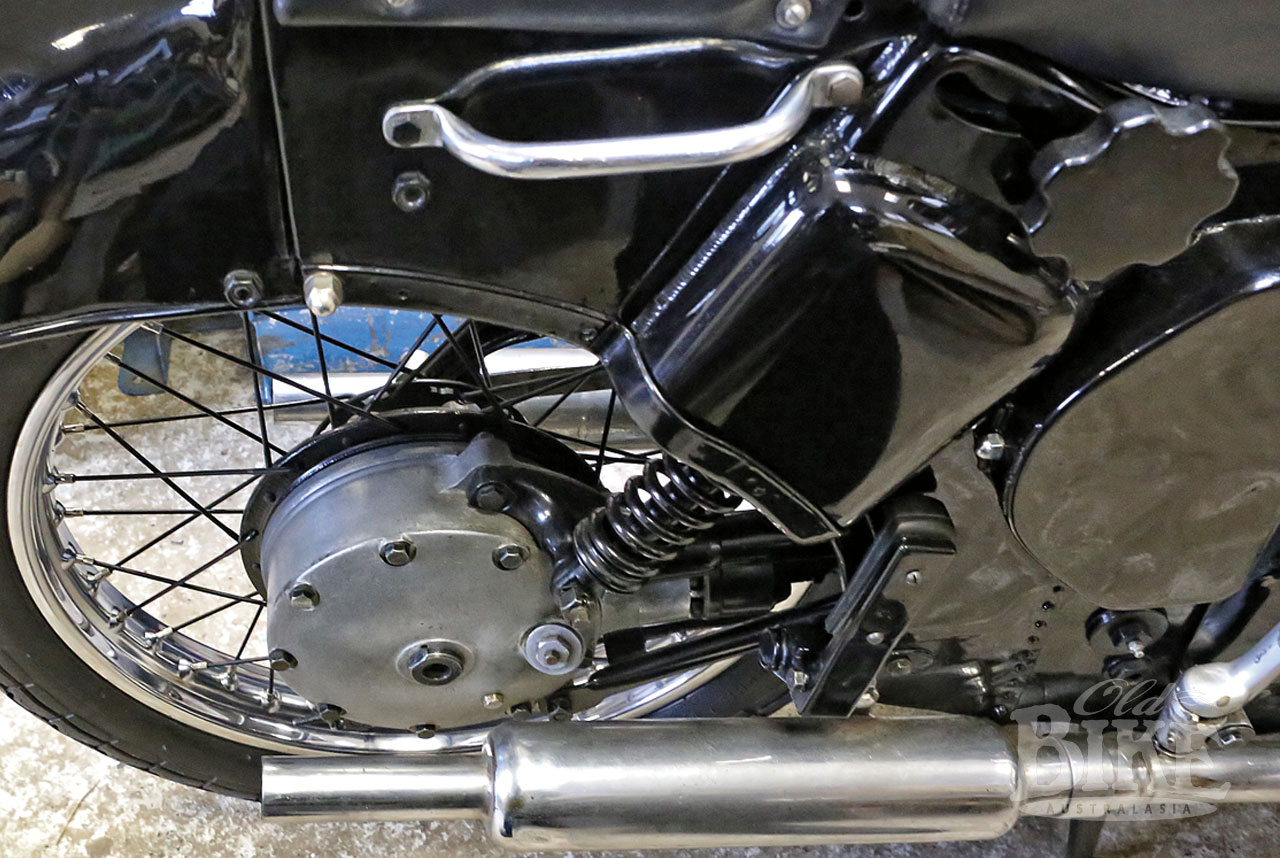

Chassis-wise, the Model O was a mixture of new and old, with swinging arm rear suspension via a simple un-triangulated rear fork, and – new for Velocette – a duplex cradle main frame. The frame was actually in two halves – a tubular steel front end bolted to a pressed-steel monocoque rear. The rear section of the frame was what Irving called, “a cleaned-up version of the stressed-skin tubeless construction which I had invented and added to a standard MSS some months before.” Like many subsequent Velocettes it incorporated adjustment for the rear springing, whereby the suspension units pivoted at the bottom and could be swung forward and backwards in a top channel to compensate for varying loads. The whole rear end was hinged so that it could be raised for rear wheel removal. The entire front end was standard MSS except for a stiffer spring in the girder forks.

When the prototype Model O was complete and running, Phil, as usual, chose to do the road testing himself. He found the machine could attain 95 mph, which led him to believe the power output to be around 30 horsepower, the cooling adequate on everything except on long uphill runs, where he felt the engine tighten. As a result, the oil pump gears were widened to give greater delivery, but Irving felt that a larger sump was the real solution. He also added a third plate to the clutch, which he described as being “only just adequate and did not like being slipped under power.” A larger left side flywheel was fitted to increase inertia by 50 per cent.

It all looked promising for the Model O, but then along came the small matter of World War II. The prototype was, like the Roarer, shoved to one side in the Birmingham factory as the war effort intensified, and it was still there when the company finally went under in 1971. It was eventually acquired from Bertie Goodman, along with The Roarer, by the noted collector and author John Griffith, reportedly in a swap deal for some antique furniture. After Griffith’s death in a motoring accident, stalwart of the vintage scene “Titch” Allen purchased the Model O from Griffith’s estate. Allen was a keen rider of all sorts of vintage bikes, and put in several thousand miles on the ‘O’. At one stage he experienced trouble with the plain big ends and had them converted to use standard British Leyland components. One thing that he didn’t fancy was the attention to comfort, describing the seat in unflattering terms. “It’s made like a saddle with mattress springs underneath, but is too small and bottoms most of the time on the monocoque frame. It seems unbelievable that Velo, who originated the dual seat as we know it, only saw it as a racing aid and missed this opportunity to build an upholstered version into the design.” What he did praise was the almost total lack of vibration. He noted, “On the move the O feels not at all like a parallel twin but more like a four. In fact it feels more like an Ariel (Square) Four than anything else, which is not surprising when you remember that its layout is like half an Ariel Four but turned around 90 degrees. Even if you rev the engine in neutral and place your hand on the tank there is still nothing you could call vibration, and certainly none of the leaping up and down we are used to with twins, and the tingle of fours. Nor is there any sign of torque reaction – and nor should there be with this technically ideal layout.”

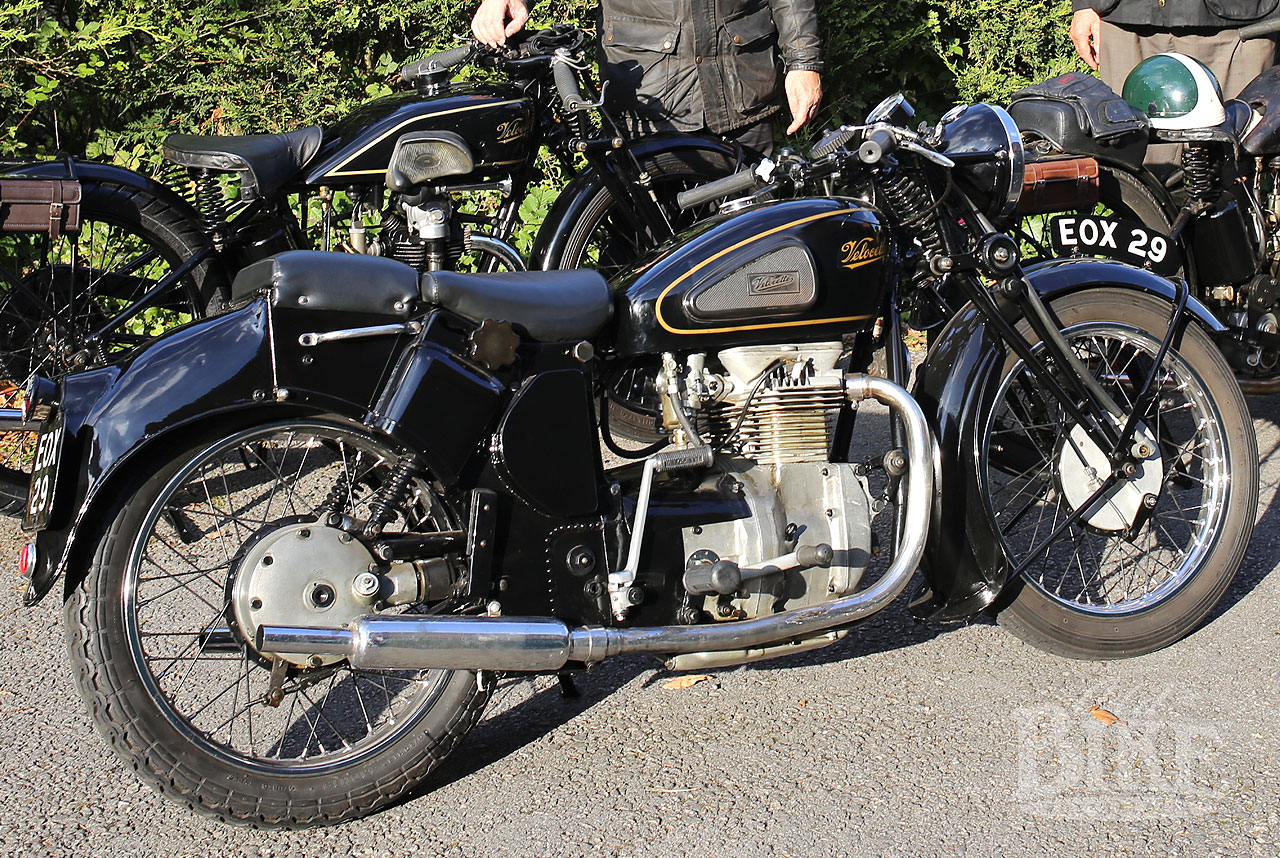

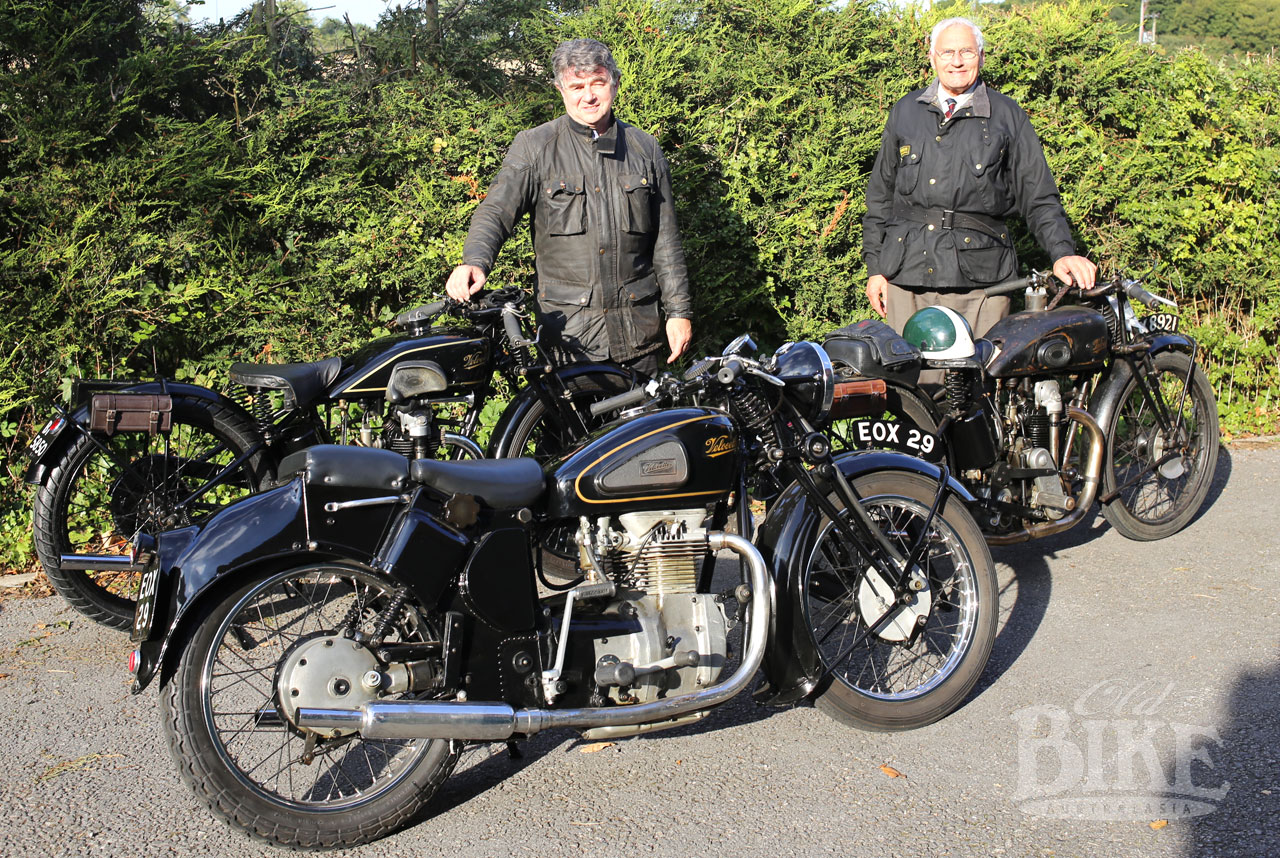

Like The Roarer, the Model O eventually became the property of Velocette expert Ivan Rhodes who undertook a complete refurbishment. And it was thanks to Ivan Rhodes that Australia’s Velocette legend Dennis Quinlan was given the opportunity to ride the famous and unique machine. Here’s what he found.

DQ rides the ‘O’.

The Australian engineer Phil Irving, “PEI” to many, worked at the Velocette factory twice in the period 1930-1942 and during that time assisted in design and alterations to existing models in the Velocette range, but in 1938 he was given the brief for the design of a road version of the 500 twin supercharged racer, called “The Roarer” by Harold Willis and which Charles Udall worked on up to the 1939 IOM Senior TT. PEI’s brief was for a pushrod un-supercharged 500cc twin with contra-rotating engine cranks and shaft drive.

The bike never went into production, WW2 put paid to that, and only the one prototype was made and survives to today, passing through several owners hands after Veloce Ltd went into liquidation in February 1971 and is currently in the stable of UK Velocette man, .

On several recent visits to visit Ivan in the UK I had rides on the Model O. September 2013 saw UK Velo LE Club Historian, Dennis Frost, come up to see myself and Ivan and he brought up a Mk.1 KTT with him – seems a ride was possibly on the cards. After lunch at Ivan’s local pub, Ivan wheeled out the 1928 350 IoM TT winning works OHC Velocette racer for me and the “O” for himself. A helmet for me was rustled up and we all set off for the lanes and byways outside Borrowash, Derby. How was the TT winner I hear you say? That’s for another day, but in a word, wonderful.

After some 7 miles Ivan stopped and handed the “O” over to me. What goes through one’s mind at this sudden unexpected generous offer – a one off – a thrill for sure! After the TT winner, so light and nimble, the “O” was heavier – I spent a moment as it idled feeling for vibration on the fuel tank, speedo, forks etc, but there appeared to be almost none, which was confirmed as I rode it. I have to admit as I took off I stalled it – crikey! But this was a chance to see how it started, hot, under such conditions. Then I thought of a comment by PEI in his autobiography (what a wonderful read) when he visited the offices of “Motor Cycling” in London in 1930 and spoke with journalist Dennis May who was perusing some copy he wrote, a road test, that had escaped the Editor’s blue pencil. “The engine would start at ‘the brush of a carpet slipper’!”

Not quite so with the “O”, but two or three kicks saw me ride off to catch up with the others.

The seat height is a little on the low side to many Velocettes I’ve owned and ridden, and the steering felt a little on the heavy side on the first left-hander I rushed into, but then I’d just come off a nimble racer. Acceleration was “adequate”, although I wasn’t about to thrash it, and the gearbox had a BMW feel as the “O” gearbox runs also at engine speed. The brakes were good and in no time I’d settled into the ride which ended back at Ivan’s where I let it idle when I stopped to muse at my good fortune and pleasure of riding such a special.

18 months later I was back at Ivan’s where Graham Rhodes, Ivan’s son was in attendance and to sort out the “O” for another brief ride. The “brush of a carpet slipper” was nowhere to be seen as the “O” showed its temperament. On a dead cold start, we had to change a spark plug and on initial starting with the cold engine, the head gasket was slightly blowing which Graham assured me would disappear when it was hot – and he was right.

The ride this time was much shorter and only around Borrowash, but confirmed most of my thoughts from my first ride…and there is no viewing through “rose coloured” spectacles for DQ. Would the “O” have been a suitable new model for the Velocette factory range? There-in lies a conundrum, for late last year I came across seemingly overlooked notes of PEI and others from Velocette on the development road tests of the “O” in the period 1939-42 at the VMCC Library.

It suffered many teething problems and from my observation of the starting issues spoken of earlier, more development work was needed to be done.

Summarising, the thrill of riding a one off prototype is something I’ll remember into my “dotage”.