Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Alec Fisher, Michael Andrews, Greg Heath

In the early post-WW2 years, the now-densely populated southern and western suburbs of Sydney were dotted with scrambles courses: Holdsworthy, Glenfield and the Southern Districts MCC’s track off the Mulgoa Road at Liverpool all operated in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, along with numerous oiled-dirt Miniature TT circuits such as Whynstanes, Blacktown and Walacia.

But even in those days, the march of urbanisation was constantly reducing the areas available for motorcycle sport. Within the space of two years, Whynstanes and Blacktown disappeared, and the government resumed the Southern Districts MCC’s land. The latter had gradually fallen from favour as it was located on very swampy land and usually degenerated into a mud bath. In an era when many competing machines were ridden to and from the circuit, riders began to favour the more civilized dirt tracks over scrambles.

The scrambles brigade, which was nowhere near as strong in NSW as it was in Victoria, instigated a search to find a replacement for Southern Districts. One of the areas inspected was the site of the later Amaroo Park complex, but this was rejected as being unsuitable due to flooding and the rocky nature of the terrain.

Racing had taken place on occasions at the Glenfield Army Camp, and when the R.A.E.M.E. Army Motor Cycle Club was formed in January 1953, high hopes were held that the new club could wield sufficient influence to have the site reopened. In Tamworth, local identity Harry Pyne worked hard to establish a scrambles track, and at Greta, Maitland MCC promoted several ‘Open to Centre’ Moto Cross events on a one-third mile hillside track. Wollongong also briefly had a track at Sheppard’s Oval, but Sydney remained devoid of such a facility.

When it became obvious that Glenfield was lost, the Army club turned its attention to a patch of land on the banks of the Georges River at Moorebank. Here a training track for Dispatch Riders and even tanks had been gouged out of the scrub along the banks of the river, and consisted of mainly deep sand and swamp. With the influence of several key army officials, notably Staff Sergeant Eric Moore, Colonel Martin and Captain Pickering, the track was extended to encompass the neighbouring rolling hills, and unveiled to the public in a ‘test’ day on October 4th, 1953, where leading riders Phil Charwood and Charlie Scaysbrook powered around the track. In a ruse similar to the creation of the ‘scenic drive’ at Mount Panorama, the Moorebank track was officially a training circuit for Military Police, but permission was soon granted for a race meeting on November 15th, with Tamworth MCC joining several Sydney clubs. Stars of the day were Rob Robinson from Bankstown Wiley Park club and Royal Dungate from Central.

The first Open meeting took place in May 1954, titled the City of Sydney Scrambles Championship, and on July 4, the state titles were held, attracting a crowd of over 5,000. This time the standout rider was all-rounder Monty South, who won the 250cc, 500cc and Aces Invitation, with Chas Scaysbrook taking the Junior. The meeting also marked the debut of 16-year old Kelvin Carruthers, who amazed onlookers by taking third place in the Junior final.

Hereafter the track saw action regularly and improvements were made, usually when Eric Moore could divert army earthmoving equipment onto the site. It is said that Moorebank had an atmosphere all its own, and that was probably because on the highest point of the land sat an innocuous white building – the Casula Sewer Treatment Works. The effluent from this establishment found its way to the river via the swamps; a natural filtering process taking place as the sewage passed through the river’s sand banks. In the Christmas months high tides would often sweep away the evil-smelling pools and leave the area reasonably tolerable to the nostrils. In all, it was a fairly undesirable piece of ground, so it was the perfect spot for a scrambles track.

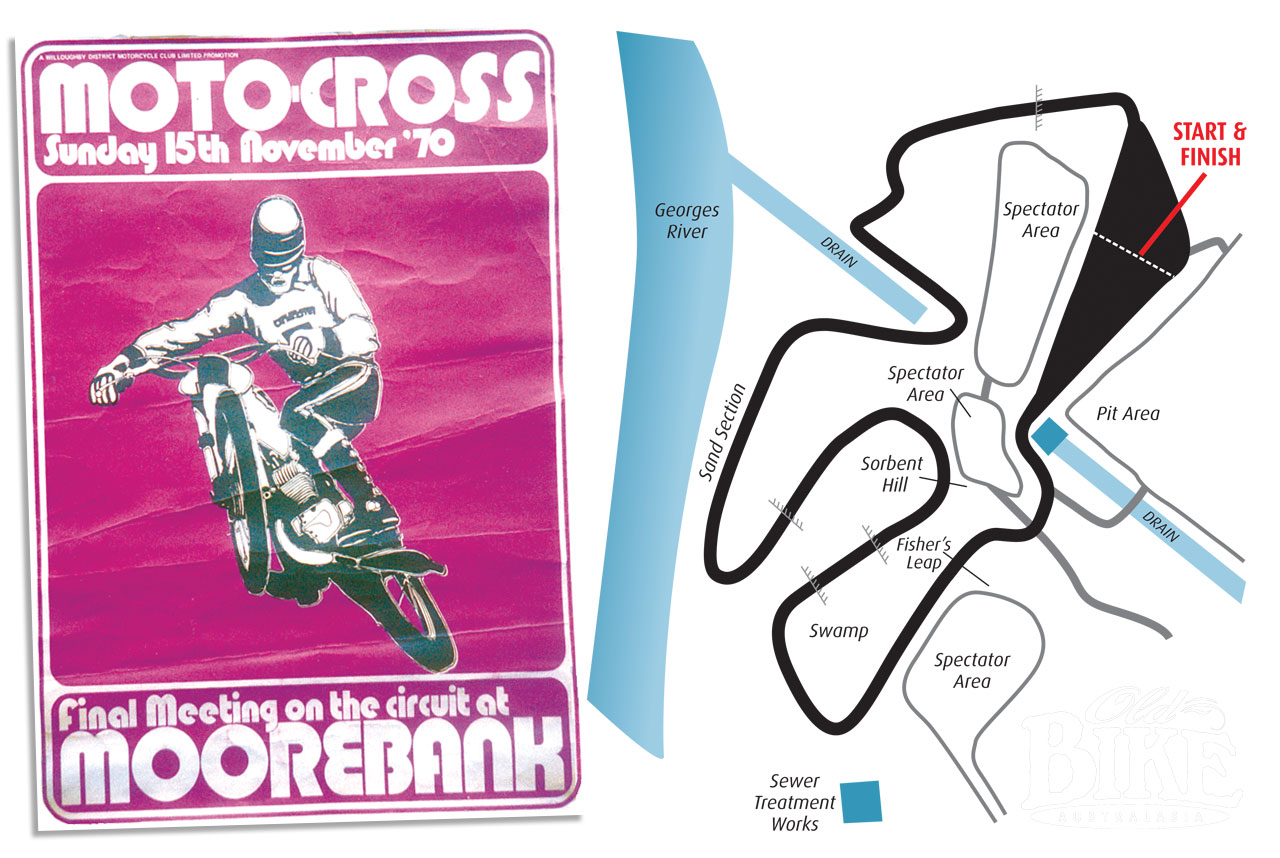

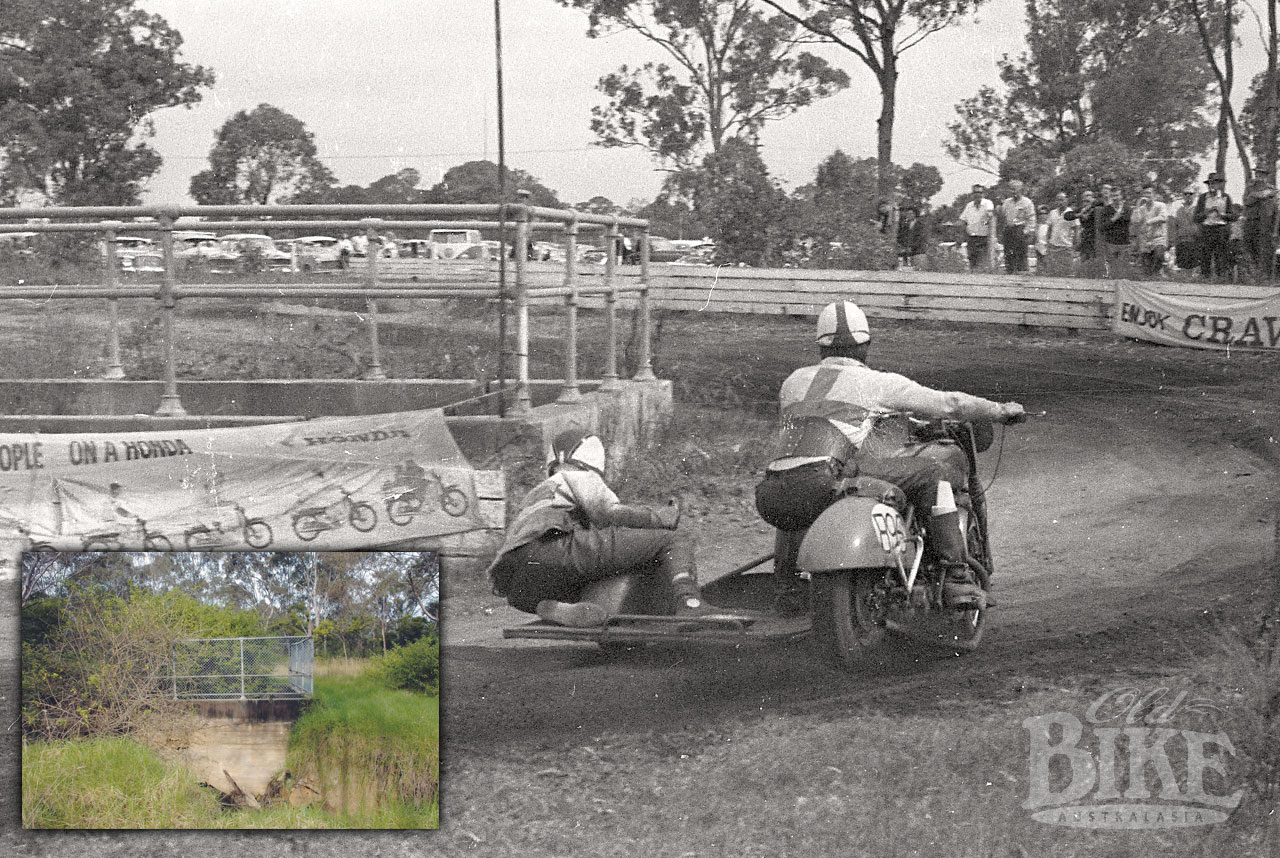

Although detail changes were made, the basic layout of the circuit remained intact for almost two decades. A concrete storm water drain which ended in a 15-metre culvert bisected the area, and this dictated the use of the available land. The starting area was laid out on the only reasonably flat piece of hard ground, adjacent to the pits. From an area more than 25 metres wide, which sometimes saw more than 50 machines face the starter, the track funnelled down to a mere four metres.

This first, unnamed, corner was the scene of many a mass disaster. The survivors then took a sweeping right turn through a dip, followed by a downhill left hander. This led to the signature section known as The Leap, later called Fisher’s Leap. Phenomenal heights could be attained from this mound. Even in those days of rigid frames and rudimentary front suspension, riders would soar for more than 10 metres, aided by a nicely sloping “landing area”. After negotiating two right hand bends, the field plunged into a vast expanse of pungent mud, the runoff from the sewer plant, which contained liquids powerful enough to cause temporary blindness and attack unprotected aluminium. Following the mud-bath, the now-unrecognisable riders struggled through the notorious sand tarp. This was in fact the banks of the river, a 200 metre section of fine powdery sand that gradually churned itself up into gigantic waves. The lower section of the culvert was crossed next, then back up the river banks to the starting area. In the late 1950s a new section was added to bypass the swamp before the sand. This long infield lop added considerable length to the track and included a steep mound with a near vertical drop. Sorbent Hill was named after its ability to inflict involuntary bowel movement from anyone attempting an overly-brave assault.

Following the race meetings, patrons would adjourn a few hundred metres back towards the main road to the Army village, where the competitors could wash the track out of their eyes and quaff the odd ale at the Sergeant’s Mess. Army personnel, riders and their wives and families, spectators and officials would relive the day’s events in the mess hall before struggling off home to refit the lights and road gear to their bikes.

The prizemoney in the mid 1950s often totalled over £300 – well worth chasing considering the weekly wage was around £20 per week.

As testimony to Moorebank’s growing stature, the Australian Scrambles Championships was awarded to the Sydney circuit for May 1956. The national titles had only been contested since 1953, when they were held at Korweinguboora in Victoria, moving to Sheedow Park, South Australia in 1954 and Mosman Park, Perth the following year. In the months preceding the big event, members of the Southern Districts club, the army and others toiled long and hard ti improve facilities at Moorebank, adding a canteen, toilet bocks and a commentator’s tower – all of which survived to the very end. A mammoth crowd poured in to see the glamour entry which included five West Australians, led by Unlimited and 350 title holder Peter Nicol, five South Australians and a large Victorian contingent. On the day, the interstaters gave the locals a riding lesson, with second in the 250 by Blair Harley and third in the 500 by Charlie Scaysbrook the only placings by NSW riders. Victorian George Bailey took the 125, 250 and 500 sashes back home, while Peter Nicol retained his 350 crown. To really rub it in, the Unlimited Championship saw a clean sweep to WA riders, with young BSA-mounted Charlie West winning from Nicol and Don Russell. It was a grand meeting, and one that was talked about for many years.

With the success of the championship and subsequent meetings in 1956 and 1957, scrambling was booming in NSW and indeed all over the country. However the motorcycle trade was beginning to show the symptoms of the plunge in sales that all but wiped it out over the next decade.

Then in April 1959 came the blow that brought motorcycle sport to its knees in the state – the New South Wales Speedways Control Bill. Under this Act, all motor sporting venues had to conform to rigid safety standards, with safety fences bordering the track and spectators restricted to wire-fenced areas. The move had been precipitated by a number of accidents, primarily involving speedway cars ploughing into spectators, but a car accident at Mount Panorama where a competitor fatally injured a flag marshal also added to the strict policing of the Bill. Moreover, the Bill made no delineation between the many types of tracks and their uses. In the eyes of the law, scrambling produced the same risks to the public as Grand Prix car racing.

Faced with the crippling costs involved in conforming to the new laws, tracks closed down overnight. Short Circuit tracks in the bush struggled on for a while illegally, then died. Moorebank was one of the first casualties, despite the fact that there had never been an accident involving a spectator. The Sydney Showground Speedway, which ironically had been one of the main causes of the dreaded legislation, was the first NSW circuit to be licensed under the new Act. Salty Creek Short Circuit in Newcastle followed soon after, but it was the Willoughby District MCC in Sydney that revived the flagging heartbeat on scrambles racing in NSW. This mall but razor-keen group of enthusiasts, most of whom lived clear across the other side of Sydney, accepted the new laws with regret but set about bringing Moorebank into line.

Many a thankless weekend was spent by the Willoughby members, aided by enthusiasts from other clubs, and finally the circuit was passed and issued with NSW Speedway Licence Number Three. The upper reaches of the track was now encased in sturdy wooden fences, strong enough to withstand the rigours of a Demolition Derby or a wayward speedcar. Patrons now longer roamed free over the ground. Instead, spectators were confined to the upper section of the circuit, and allow this still provided fine views of the racing, public access to the spectacular sand section was no longer possible.

These problems aside, at least the circuit was back in business, and the state’s race-starved riders turned up in droves. Former road racers, short circuiters, in fact everyone who wanted ride in New South Wales rode at Moorebank. But while it was an occasion for much rejoicing from the racing fraternity, motorcycle shops were disappearing rapidly as the sales slump worsened. Listings in the Sydney Pink Pages went from nearly three pages to half a column. Sporting events were also being hard-pressed to attract spectators, now that the small screen was beginning to get a grip on people’s minds and leisure habits. Moorebank can claim the historical distinction of being the first direct outside broadcast event covered by Australian television.

With trade support dropping to almost zero, the promotion-minded Willoughby club successfully wooed backing from a number of other sources. They formed a strong alliance with the Liverpool Rotary Club, which was handy to maintain a reasonable social status, as the use of the land was always being challenged by somebody in a position of authority. They also gained on-going sponsorship from the Craven A cigarette brand.

About this time, home-grown stars Les Fisher and Roy East returned from Europe, and everyone was keen to see how they had benefited from the international experience. One of the first clashes was at the NSW Championships in 1958, when Victorian Bob Walpole also appeared. However the hoped-for duels were all but washed away in the atrocious conditions, with metre-deep streams running arcoss the track. Fisher revelled in the mire but suffered machine problems all day, while Walpole rode consistently to take the 500 and Unlimited titles.

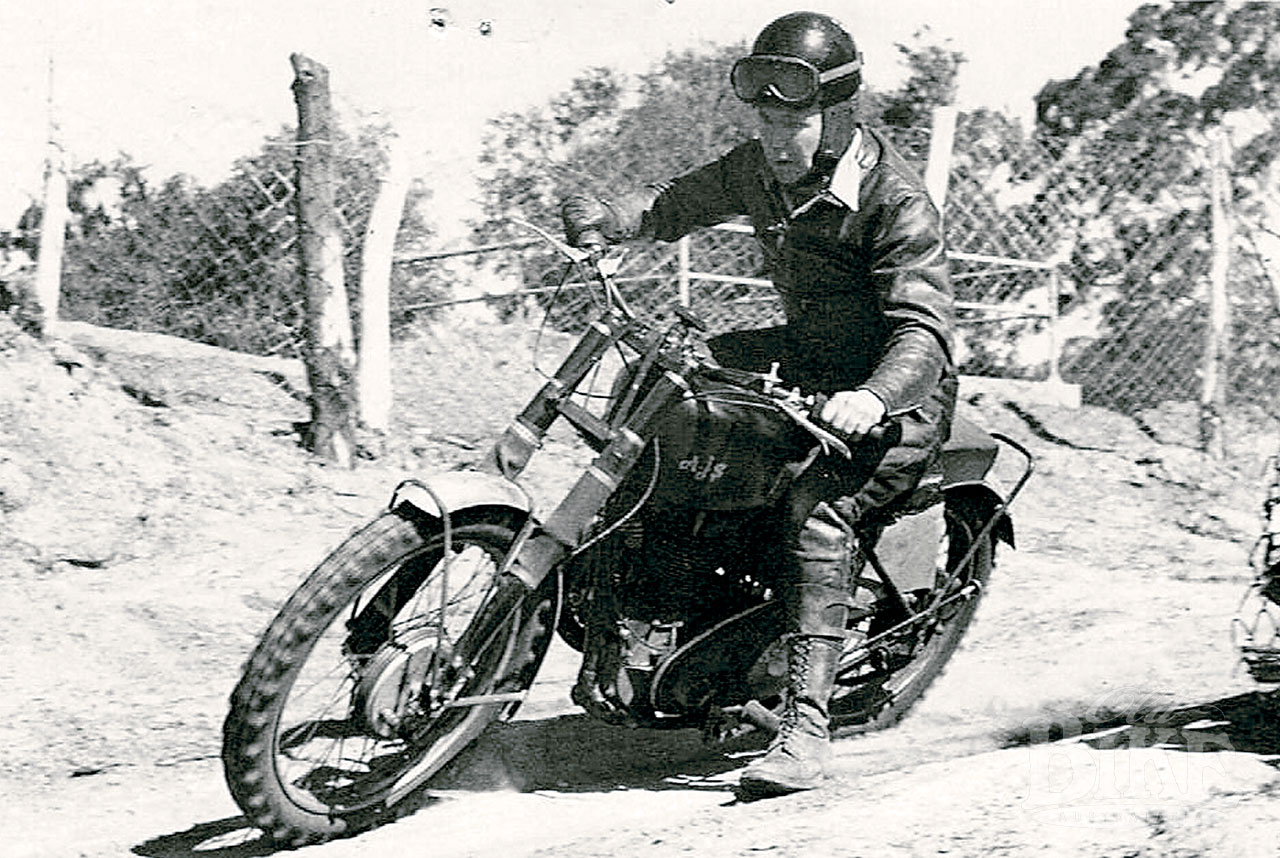

For the next few years, while motorcycling sank to its lowest-ever depths, scrambling at Moorebank went from strength to strength. By 1960 huge fields entered for every meetings, and Willoughby club responded by holding an event almost every month. There were plenty of cheap bikes around to convert to scrambles use. Les Fisher continued to reign supreme and he and his BSA were a match for most of the interstate riders who appeared from time to time. Opposition came from many sides, but no one rider stood out like Fisher. ‘The Leap’ became Fisher’s Leap, in his honour.

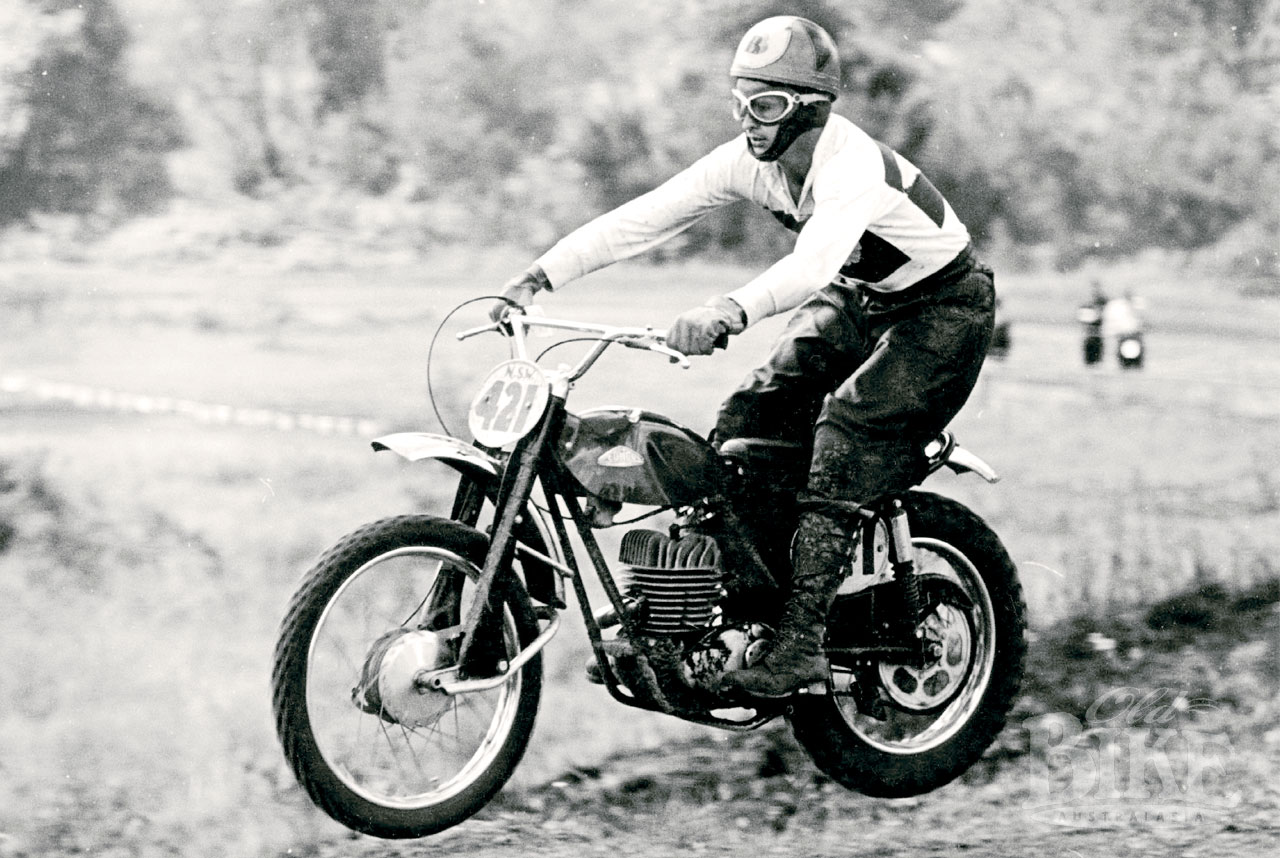

In 1961, Moorebank was again awarded the running of the Australian Championships. Just like five years before, Western Australian riders were in a strong position. Charlie West, now with European experience behind him, brought his immaculate fleet of three BSAs, fettled by his father, affectionately known as ‘Pop’. West was accompanied by reigning 250 Champion Gordon Renfree and Glen Britza, who brought with him one of the first of the new-fangled English scramblers – a Greeves Hawkstone. While the lanky Britza’s fiery style brought him undone on the day, the speed of this ungainly looking machine made a lasting impression on everyone. Big John Burrows was there to represent Victoria with another Greeves and his 500 AJS. NSW was relying on Fisher, but young Jim Airey, later to become multiple Australian Speedway Champion, looked a chance for the 350 title. As well as every keen scrambler with the means to get there, the programme contained the names of Len Atlee, Eric Hinton and Ron Toombs; all leading road racers of the day. The third and final leg of the Senior Championship was probably the single most famous race ever staged at Moorebank. Fisher and West went into the round locked on points, having won a leg each. For most of the race, Fisher, mounted on Lindsay Cooper’s Triumph/BSA hybrid, tried everything he knew to outrace West’s 500 BSA Gold Star. Spectators ran in droves from one viewing spot to the next, following the spectacular battle as it raged around the circuit. Fist Fisher led, then West, until Fisher misjudged a corner and found himself motor-deep in the putrid swamp. Still not defeated, he struggled free and began a seemingly impossible chase, regaining the lead on the next-to-last lap. Never was there a more popular victory at Moorebank, but West had the consolation of taking both 250 and 350 titles. NSW took another title when veteran Ray Dole on his Victa lawnmower-powered BSA Bantam won the Ultra Lightweight. Charlie West became a regular competitor at Moorebank, driving between Perth and Sydney and often combining scrambling at Moorebank and speedway racing at Claremont in the same week.

The Australian Championships were a sign of things to come. The new breed of lightweight 250 two-stroke had rapidly emerged as a serious competition mount and within a few years would dominate the entry lists. The tremendous growth of speedway-style short circuit racing badly dented the fields at Moorebank in the mid 1960s. It seemed no-one wanted to get dirty any more, and the emergence of the specialised two-strokes scared a lot of would-be riders away. Cotton, DOT and Greeves were the most popular of the new lightweights, at least until Bultaco, Montesa and CZ appeared on the scene. In the hands of regulars like Graham Bartholomew, Ron Kivovitch, Col Evans and all-rounder Kel Carruthers, they dominated the scene.

Something Moorebank can claim is the first direct telecast of motorcycle racing in Australia. Held on Saturday 2ndNovember, 1963, heats and lesser races were run in the morning, with the first feature event (Race 9) scheduled to coincide with the tv coverage commencing at 3pm. Ray Dole recalls that “most of the field crashed in the first 100 yards and the race was topped. Because of the television being live, they cleared the machines away and went straight onto Event 10, followed by the sidecars. The live coverage was to finish at 4pm, but the station had received so many calls from satisfied viewers, they decided to combine the scheduled show until the end of the scrambles programme at about 4.40pm”. I wonder if this vision still exists?

In 1966, Graham Bartholomew, the Wollongong rider who was sponsored by arch-enthusiast Geoff Martin (formerly mechanic to speedway legend Aub Lawson), relinquished his ride on the latest Villiers Starmaker-engined Cotton for a hybrid mount which comprised a speedway JAP motor in a modified Cotton frame. This he-man’s bike proved difficult to tame, but more significantly, Graham’s vacant 250 Cotton was taken over by young Queenslander Matt Daley, who was apprenticed at Martin’s engine reconditioning shop in Wollongong. First on the Cotton, and then on the first 250 Husqvarna to come to NSW, Daley swept all before him. His only serious opposition came from Laurie Alderton, riding the ageing BSA Victor. By now Moorebank itself, after close to 15 years as the state’s only scrambles track, had opposition as Mount Kembla in Wollongong and Bilpin in he Blue Mountains came on stream.

An ambitious move by a combined group of promoters saw Moorebank stage its first, and only, international meeting in 1968. Randy Owen and Gordon Adsett represented England, with an unknown Austrian, Alfred Postman, and New Zealand stars Alan Collison, Ross Mclaren and Brian Franklin. Not surprisingly, Owen and Adsett ravaged the field on their 360 CZ and Husqvarna machines, leaving Australia’s best looking very second hand.

By now Moorebank was beset with problems. The army connections had weakened considerably with the departure of the ‘old school’. With the advent of the Vietnam war the military found the excuse it needed to back their arguments to resume the land. Even Willoughby president Len Main, who had guided the circuit’s destiny for a decade, was fighting to keep club members interested in the promotions. Seventeen years before, the river bank on the Liverpool side was an unblemished bushland; by 1970 it was a mini-city.

Civilization had caught up with Moorebank. Everyone knew that the end was near. So when, on November 15, 1970, the final curtain rang down, it came as no great surprise, and Moorebank passed on with scarcely a tear shed. Willoughby already had its eyes on Amaroo Park. A full programme was contested that day, but the event that had very spectator straining the fence wire was the Veterans’ Race. A nostalgic field of old timers lined up; Frank Mayes, Charlie Scaysbrook, perennial 125 winner Ray Dole, Graham Bartholomew, Phil Charlwood, Eric Debenham, Monty South, and lots of others. Everyone had a ball, quite a few got drunk at the Boorelog (nowadays referred to as a barbeque), and the trailers trundled out of Moorebank late that night, for the last time.