September 28-29, 2019 marked sixty-two years since the BP-C.O.R. Speed Tests on a dusty, blustery country road in outback NSW. The occasion passed without any official celebration, but the story is as incredible as ever.

Since motorised wheels began turning, the challenge to be the fastest thing around has preoccupied mandkind. The primary considerations have always been to have a fast vehicle, a big heart, and to find a suitable site. One would imagine that in a country as vast as Australia there would be no shortage of long, straight stretches of road that could be used when winding a vehicle up to previously unattained velocity, but the reality is a quite different thing.

What became known as the Tipperary Mile would never have happened without the thaw in the cold war between the big oil companies, who had an agreement (at least in Australia), not to support motor racing in any (overt) way. In a short space of time, most of the oil companies forgot the previous arrangement and began to actively back drivers, riders and events. Not just in racing, but record breaking.

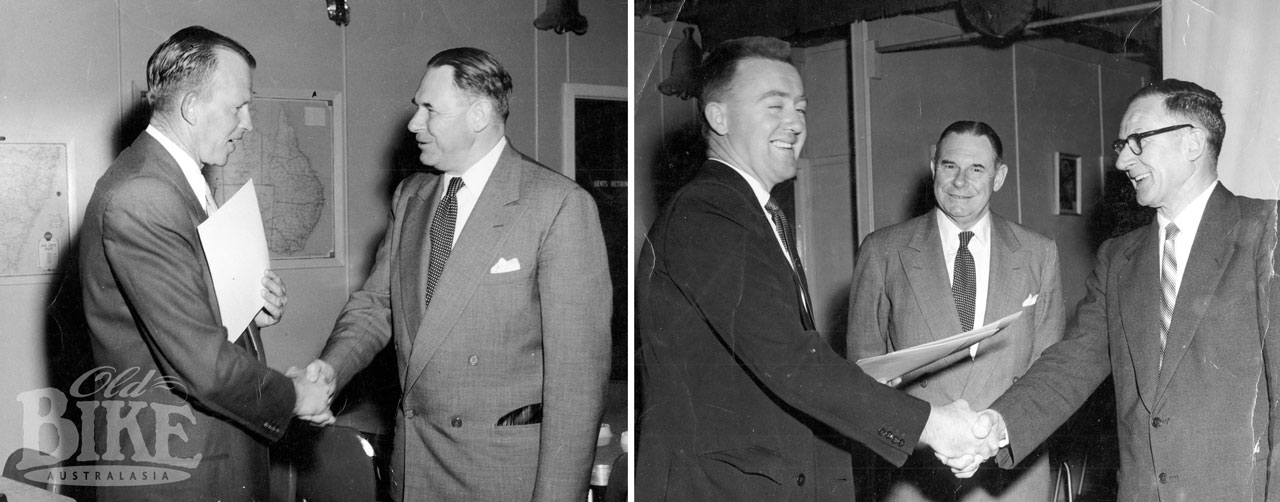

It was in early 1956 that Graham Hoinville, at that time working for C.O.R. as Automotive Lubricants Engineer, began scouring the country for a location that could be used for attempts on the Australian Land Speed records. Through its local subsidiary, Commonwealth Oil Refineries (COR), BP had signified its willingness to underwrite such attempts by its contracted car and motorcycle racers. Underwriting was one thing, organising the venture was quite another. It took Hoinville and his helpers more than a year to eliminate all but one site; a dead-straight four-mile stretch of country road that ran beside a railway line between Coonabarabran and Baradine in north-western New South Wales. The centre section of this road ran past the gates to Tipperary Station, so the exercise came to be known as the ‘Tipperary Flying Mile’. Organisation of the actual event fell to a team headed by John Pryce in his new role as motor sport manager for BP.

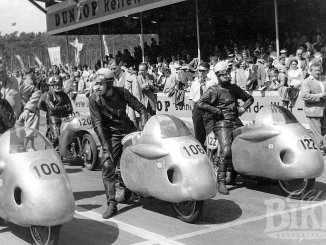

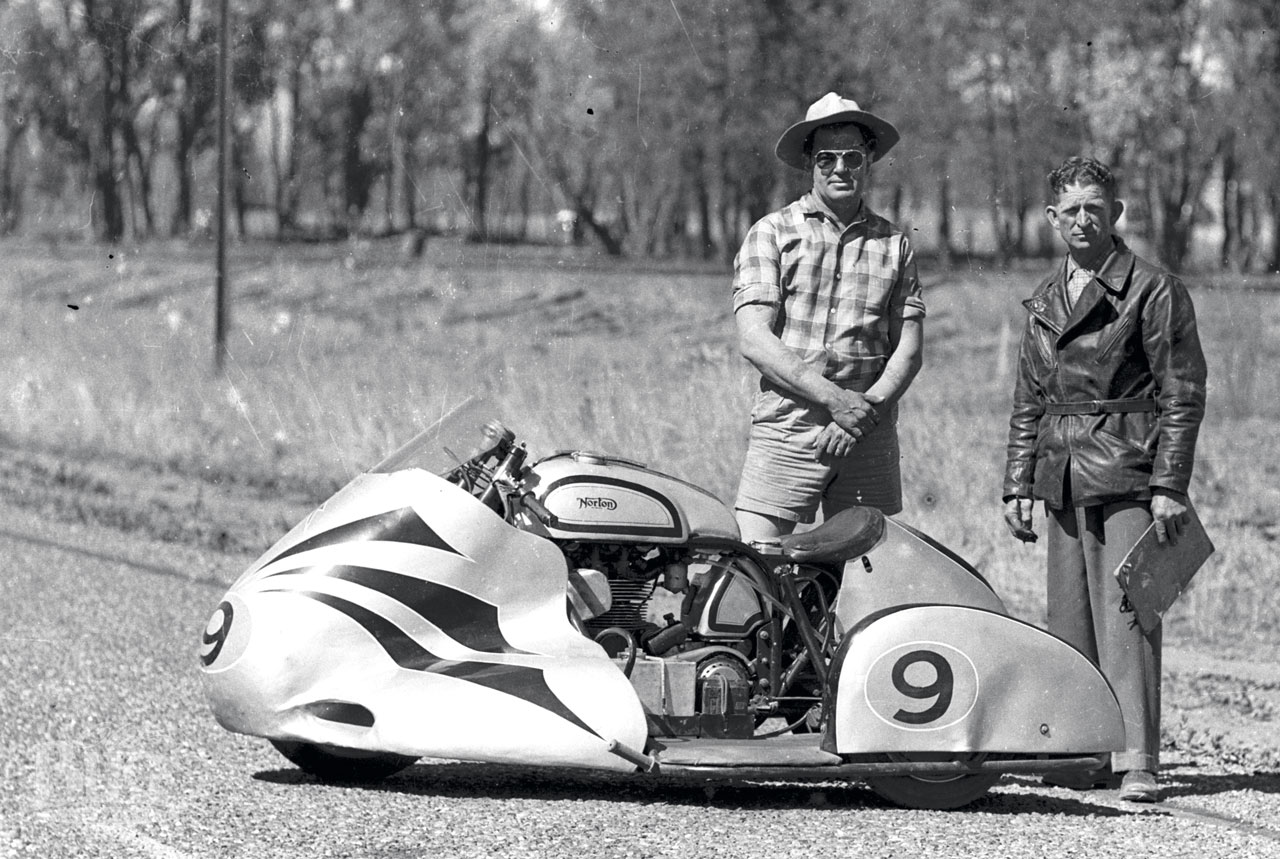

Primarily organised as a car event, it was only late in the piece that BP decided to include their motorcycle riders. Those invited were Jack Forrest, with his ex-works 500cc BMW Rennsport, Trevor Pound, who brought along the famous 125cc BSA Bantam owned by Eric Walsh as well as the very successful 350cc BSA/Norton hybrid owned by Melbourne tuning wizard Jimmy Guilfoyle. Jack Ahearn had his 350 Manx Norton and a 250cc NSU Sportmax. Sidecars were represented by Frank Sinclair’s 1000cc Vincent and Bernie Mack’s 500 Norton.

Blow me down

The official BP-COR Speed Tests were set down for the weekend of 28th and 29th September, 1957, and as is usual at that time of year, strong winds swept the district, at one stage threatening the postponement of the competition. Despite the Flying Mile appellation, the records were actually contested over a flying kilometre, in accordance with international rules. Although recently tar-sealed, the road was only 5.4 metres wide with a distinctly high crown. Dirt tracks leading to properties led off the road at various points, and the incessant winds continually deposited loose gravel from these onto the main road. Run off area was practically non-existent, with the railway line (flanked by telegraph poles) on one side and trees on the other. At either end of the straight stretch lay a right angle bend, meaning that both run-up and emergency over-run were strictly limited. At the drivers’ insistence, a white line was hand-painted for the entire length of the straight.

The motorcycle contingent all encountered problems of varying degrees. In an effort to raise the overall gearing of his BMW, Forrest and his mechanic Don Bain fitted a larger-section rear tyre. At maximum speed on the first practice run, the tyre grew so much due to centrifugal force that it jammed against the swinging arm, melting the rubber and locking the rear wheel. Locals say that the black skid mark in the centre of the road was still visible more than twelve months later! With no other rear tyre available, local garage owner Vane Mills vulcanised a patch on the area where the rubber had worn through to the canvas. Hardly the tackle on which to attempt to be the fastest man ever on two wheels in Australia. Forrest had another major scare when he ploughed through a flock of galahs that had settled on the road. The black fairing of the BMW bore the scars for the rest of the weekend.

A case of the wobbles

Trevor Pound, an aeronautics engineer, had taken the record attempts very seriously and designed a special streamlined shell for the Guilfoyle BSA. A wooden ‘plug’ was produced, from which a mould was made in Plaster of Paris, and from that a fibre-glass shell. A tail fin was added for stability. The cockpit cover was made as a single unit, attached to the shell by Dzus fasteners – meaning that once the rider was aboard, the cover could not be opened except by a mechanic. A hole was cut in the top for one important reason. The Guilfoyle BSA engines had been known to break crankshafts, showering oil everywhere. In the case of such an event, oil would have coated the inside of the screen, so the hole was the only way for the rider to maintain visibility! Flush-mounted spring-loaded doors were cut into the sides for the rider to push open and gain a ground foothold. At just under 4 metres in length, the plot looked neat, but once under way there were major problems. Owner Jimmy Guilfoyle took the bike out for a shake-down run and came back ashen-faced. In aerodynamic terms, the device developed a divergent yaw oscillation, which meant that above160 kp/h, the bike started a weave that gradually became worse and worse. On one run, the intrepid Pound had reached 202 kp/h in second gear when the weave got so bad that he ran into the dirt on both sides of the road, scattering officials, before he could bring it to a stop. The problem was eventually traced to incorrect weight distribution caused by excessive thickness of the fibreglass over the rear of the machine. Pound vividly recalls the tense moments as the fasteners were attached over his head before the timed runs. A wizened old farmer standing nearby muttered, “It looks like a bloody coffin and now they’re nailing him in!”

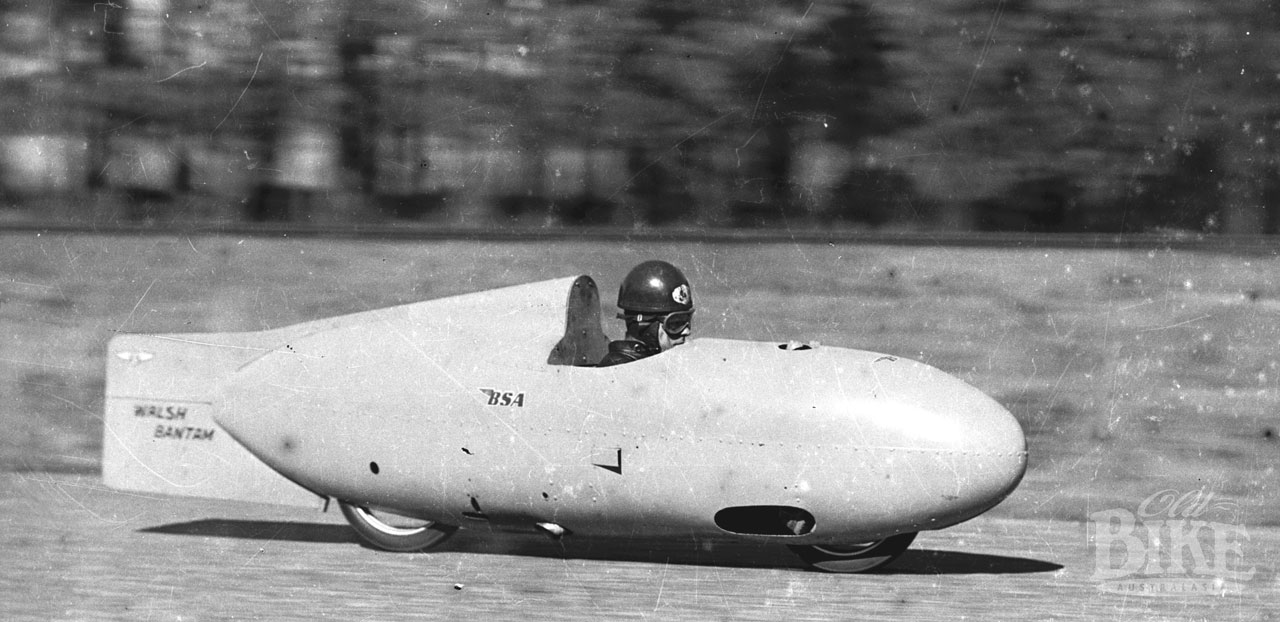

Pound’s other mount, the Walsh Bantam, had problems of its own. Eric Walsh had been severely injured in 1956 when warming up one of his engines before a race meeting. To prevent the motor loading up, the accepted practise was to scream the engine at full throttle for short bursts. Walsh was bending over the engine when the external flywheel disintegrated, and he copped the full blast in the face and head. He never fully recovered and had not run his famous machines since, until Pound suggested the record attempt. Walsh had an old aircraft belly tank lying in the back yard of his home, and asked Trevor to see if he could fit into it, laying flat. A special frame was constructed to fit inside the shell, with the engine positioned behind the rider. The old belly tank was cut about a bit and a tail fin added. The footrests were positioned on the front axle, and slots were cut in the bottom of the fairing to allow the rider to get his feet onto the ground. At Coonabarabran, the first problem the team encountered was trying to maintain control when starting the bike. The ‘lay down’ riding position meant that there was little in the way of stability at low speed. With helpers pushing the bike it was nigh on impossible to keep the Bantam truly upright, and as soon as the engine started the device would shoot off in its own direction before Pound could bring it under control. The problem was eventually solved by having two mechanics push with forked branches of a tree on the rear of the tail fin. It looked strange but kept the bike upright and meant that Pound could get the show on the road – literally – as soon as the engine fired.

A tragic start

The night before the event began, officials learned that a mob of 725 drought-stricken bullocks, which were be herded to better grazing land in the Hunter Valley, was scheduled to use the road the following day. Arrangements were hurriedly made to hold the bullocks in a nearby paddock over the weekend, with BP-COR undertaking to pay to have several thousands of gallons of water trucked in for them.

The event began in the worst possible fashion. Very early in the morning on the opening day, with the road still open to normal traffic, Sydney driver Jim Johnson decided to have an unofficial run to test his MG Special. Jim Butler, son of the original owners of Tipperary station (who purchased the property in 1961), remembers the morning well. “My wife Jenny’s uncle had a fuel truck and he was just turning into the Tipperary gates at about 6.30am when Jim Johnson arrived. He (Johnson) was not going flat out, he was listening for a misfire as the car wasn’t running cleanly and he just drove straight under the truck and was decapitated. There was nothing Jenny’s uncle could have done. There were no rear vision mirrors on the ruck so he couldn’t see the MG, and Jim wasn’t looking where he was going. “ The popular driver left a widow, Betty and an infant son.

As if this was not enough of a setback, fierce blustering winds sprang up on Saturday morning, causing the motorcycle attempts to be held over until the following day.

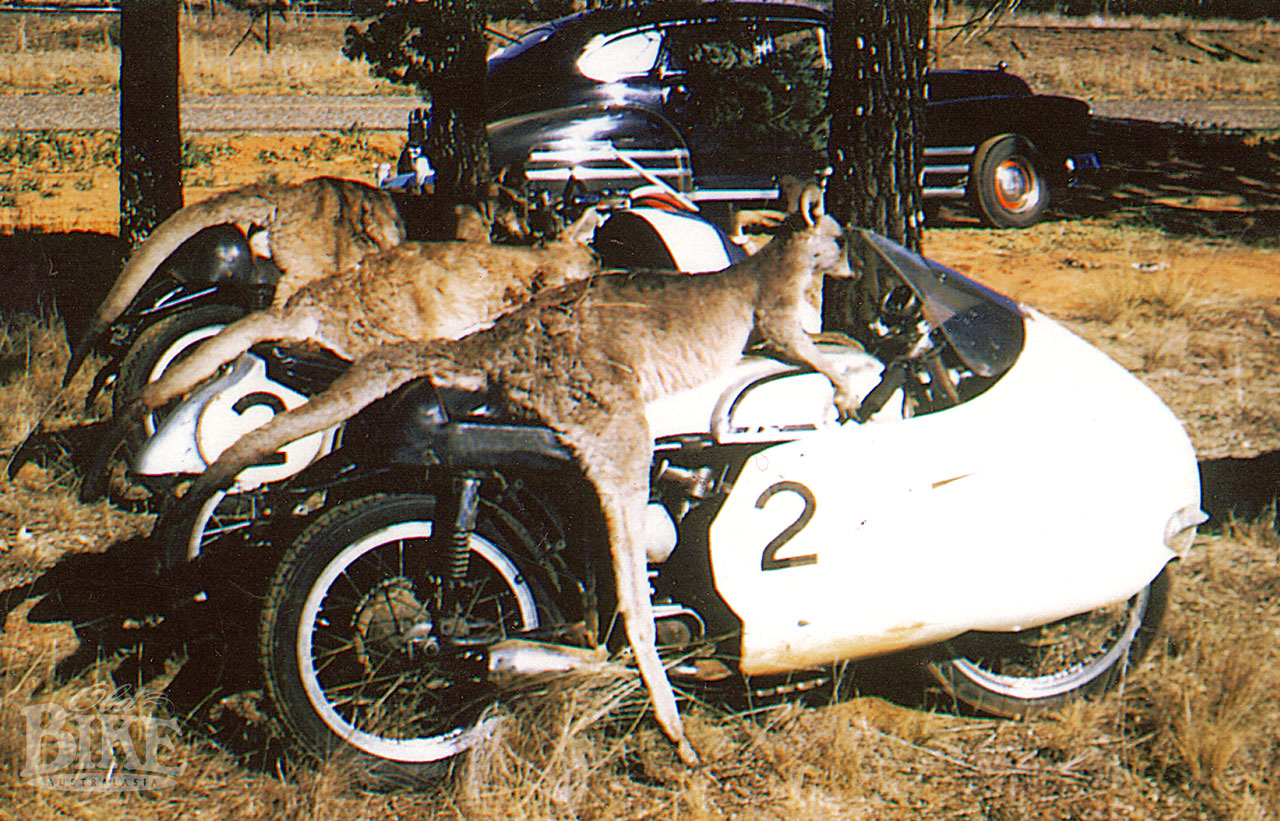

Jack Ahearn had awoken that morning to a rather bizarre sight. During the night, a bunch of locals as well as some mechanics and drivers had decided to go out into the bush shooting kangaroos, downing quite a bit of the local brew along the way. The hilarity reached its peak when several of the carcasses were dragged into the area where the bikes were parked in the open. The dead ‘roos where placed in riding position on Ahearn’s stable, and by the time dawn broke, the effects of rigor mortis ensured that it was nigh on impossible to get them off! Jack was not impressed, nor were the animal lovers in the community.

Forrest’s Pluck

The winds had abated somewhat by Sunday (but not the bushfires that continued to blaze in the surrounding scrub) and the bikes finally had their turn at lowering the records, some of which had stood for decades. With his patched-up rear tyre, Forrest blasted through the speed traps at 152 miles per hour (244. kp/h), more than 20 mph/h better than the old mark. Even then, he complained to Don Bain, that the BMW was wobbling almost uncontrollably. Harry Hinton Senior, who was assisting Jack Ahearn, advised Forrest to hold third gear and use higher revs, and the ploy almost worked. On the return run, the speed wobble became so bad that Forrest was forced to shut the throttle completely, sailing silently over the line with a dead engine. The culprit was again the rear tyre. A huge bubble had appeared on the sidewall and it was a miracle the cover did not burst. Still the average for the two runs, at 149.068 mp/h (239.9 kp/h), was a new outright and 500cc record, breaking the 127 mph mark set by Art Senior on his home-brewed Ariel special almost 20 years before. Forrest’s time was to stand until January 1973, when it was fractionally eclipsed by Bryan Hindle’s TR350 Yamaha.

Ahearn had a relatively trouble-free run on his 350cc Norton to easily break the record in that class at 125.68 mp/h (202.3 kp/h), although he reported that the bike was severely undergeared. The little 250cc NSU amazed onlookers when it was only slightly slower, setting a new mark of 121.252 mp/h (195.14 kp/h).

For Trevor Pound and his team there was only disappointment. On (or rather, in) the Bantam, Pound managed only a single one-way run at just over 160 kp/h when the magneto gave up the ghost. With no spare, his day was over with the 125. With its handling problems insurmountable, the 350 Guilfoyle BSA also made only a single run before being parked.

Both sidecars set new marks. Frank Sinclair’s Vincent averaged 124.524 mp/h (200.4 kp/h), while Mack’s 500 Norton posted 112.219 mp/h (180.55 kp/h).

As usual in those days, the cars garnered the lion’s share of the publicity, particularly for Ted Gray, whose Corvette-engined ‘Tornado Special’ finally broke the mark of 146.7 mp/h (236.1 kp/h) which had been set way back in 1930. The new record was 157.7 mp/h (253.8 kp/h), which, in context, was only slightly faster than Forrest’s time and achieved in far greater safety and comfort!

In 1997, a reunion was planned to mark the 40th anniversary of the record attempts. For various reasons this reunion was delayed but finally went ahead in early 1998, attracting much local media coverage. It featured many of the original officials and local identities who had been associated with the original event, but just one of the original competitors –Trevor Pound, who brought along his now-historic Elfin Mono for a few demonstration runs. Jim Butler, who was just a teenager at the time of the record attempts, assisted with the organisation of the reunion, but sold the property the same year and moved to Alsonville.

There was much enthusiasm for a similar reunion to mark the half-century of the Tipperary Flying Mile, but time has taken its toll and the date passed without a wheel being turned on this historic, narrow and somewhat desolate strip of bitumen in the Australian outback.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook Photos: Charles Rice, Jim Butler