The Japanese factories wanted 350s for the booming US market. Yamaha got there first.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

Yamaha called their first 350 the YR-1 Grand Prix (at least they did in USA), which was ironic because the initial target was not the Grands Prix of Europe, but the blue ribbon event stateside, the Daytona 200. It really was a punishing event; the flat out howl around the notoriously bumpy banking stretching both engines and chassis to their limits, plus the heavy braking and cornering requirements of the infield section. Success was seen as vital to sales, and everyone wanted to unseat Harley-Davidson from their long-held perch at the top. The Daytona regulations, cooked up over decades to favour Yankee iron, had basically withstood assault from the British factories, but that didn’t stop Triumph from trying in 1967, with a strong team on 500cc twins with such as Gary Nixon, Buddy Elmore, Larry Palmgren and Dick Hammer in the saddle, plus Dick Mann on a BSA twin. Honda was there too, with a team of 450 twins entered by Bob Hansen.

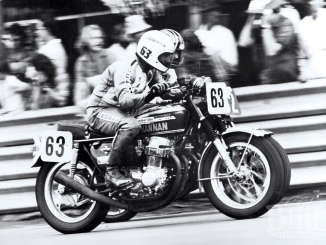

Yamaha had monstered the opposition in the supporting 250cc race, taking seven out of the top ten places for their third straight win, but that was expected. What wasn’t expected was the pair of brand new 350s, one of which, in the hands of Canadian Mike Duff, scorched around at an average of 132.742 mph on the oval to qualify 8th, only fractionally behind the big four strokes. One quirk of the AMA Class C rules dictated that entries in the main 200-miler could only use four-speed gearboxes, so Yamaha had to pluck out one cog. They chose to dispense with first gear entirely, leaving second, third and fourth as they were and substituting a new top gear. With Daytona gearing, it meant that what became first gear was a whopping 4.9:1, requiring much clutch slipping at low speeds. In the race itself, both Yamahas struck problems; Californian Tony Murphy spending considerable time in the pits changing a fouled spark plug, and Duff even longer when a split fuel tank had to be replaced. They finished 18th and 19th respectively, but left no one in doubt that in 12 months time… watch out!

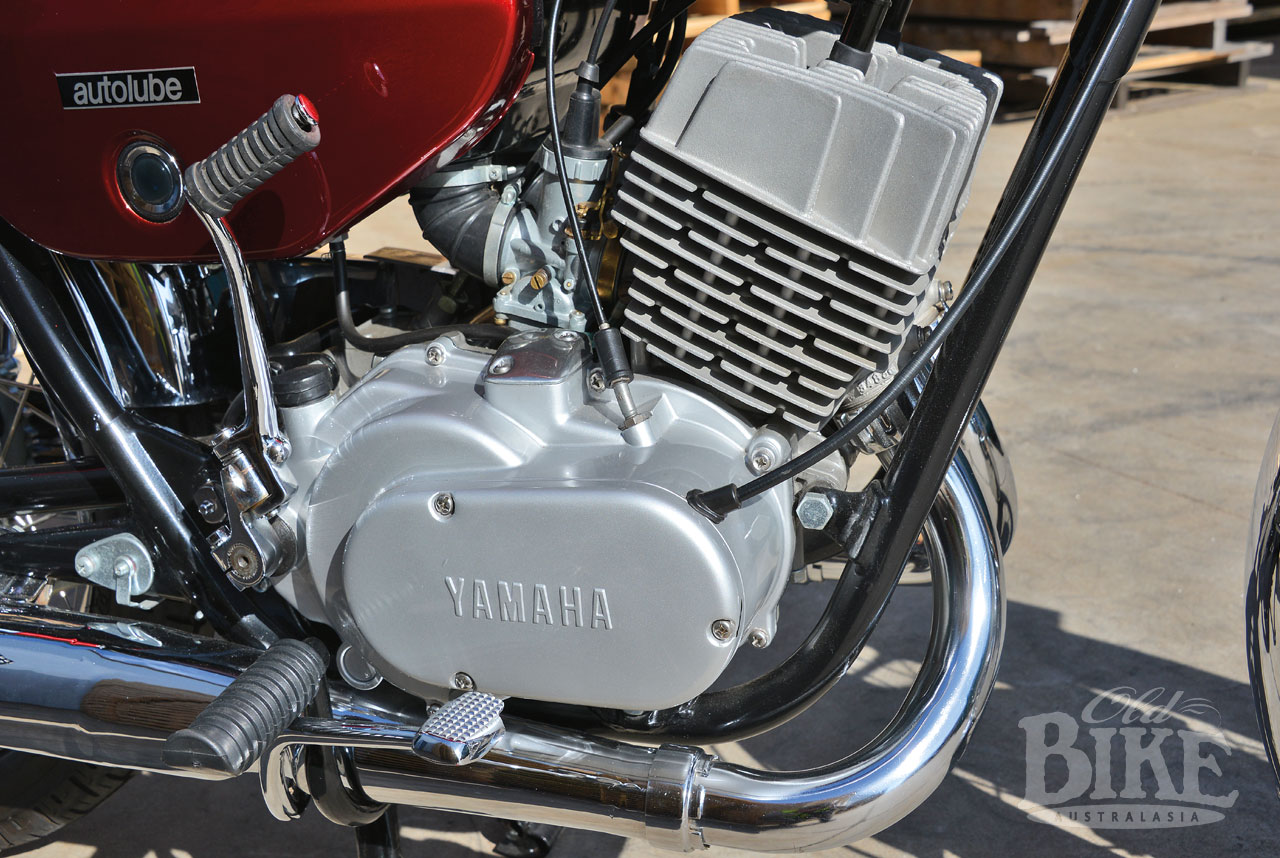

As per the AMA rules, the Daytona entries were derived from production road machines, sort of. The YR-1 had been introduced early in 1967; an all-new concept owing little to the previous Adler-inspired 250cc twins. At the heart of the matter was the new engine, with the clutch moved from its thus-far normal location on the end of the crankshaft to the gearbox mainshaft. The big disadvantage of a clutch rotating at engine speed was the tendency to grab or snatch when getting underway. By moving the clutch to the mainshaft, the plates were spinning at a fraction of engine speed, making for much smoother action, and giving the engine crankshaft an easier life.

The engine itself took on an aggressive new style, with square, or more correctly, rectangular finning for the alloy barrel, which had iron liners shrunk in – another first for Yamaha. Another first for the company was the use of horizontally-split crankcases which allowed for a much more rigid crankshaft mounting and simpler maintenance. Cylinder heads featured a machined squish band for more complete combustion. The almost-square (61 x 59.6mm) engine was listed as producing 36hp at 7,500 rpm, but even by this stage, Yamaha had a reputation for being conservative with such figures, and most road testers put the output considerably higher. The barrel sported three ports, ie; one inlet port and two transfer ports, and was fed by a pair of 28mm Mikuni carburettors fitted with large capacity washable paper filters. As well as delivering a clean mixture, the filters did an admirable job of silencing the traditional two-stroke inlet noise, which had been a feature of the earlier 250cc twins. As was by-now standard two-stroke practice, only pure petrol was used in the tank, lubrication coming via oil from the 4 litre tank mounted on the right side metered into the inlet port by pump, according to throttle opening. Yamaha called their system Autolube, and even at Daytona, this method was retained.

To allow for the differing entrenched cultures in various markets (notably USA and Britain), the gear change could be mounted on either left or right side, thanks to a through-shaft and fittings to allow the brake pedal to be swapped to either side.

The frame was also brand new, made from large-diameter steel tubing with heavy gusseting around the steering head and swinging arm. A cradle in every sense of the word, the twin frame tubes swept from the steering head under the engine and up to the top mounting point for the rear suspension units. In the chassis department at least, the road-going YR-1 differed from the Daytona racer, which used a slightly modified version of the Norton-style double loop frame used on the highly successful RD56 works racers; one mod that was permitted under AMA regulations. Surprisingly, the YR-1 even came with a sidecar attachment lug on the frame, but it’s a fair bet that few chairs were ever attached. Brakes were excellent for the time, particularly the race-inspired twin-leading shoe front stopper. Although measuring only 185mm, the brake worked extremely well and was fade-resistant. The rear brake was the same size, but only single leading shoe.

Styling-wise, the YR-1 followed the trend set by the big selling 100cc twin, with a pointy fuel tank sporting chrome plated side panels which were held in place by bolts hidden under the knee rubbers. Chrome abounded; from the front forks with their plated sliders and lower covers, both mudguards and the meaty exhaust pipes and silencers. As was the fashion, the speedo and tacho were combined in a single large unit embedded in the headlamp.

Because the YR-1 broke new ground as an over-250cc Japanese two stroke (although it was soon followed by other twins from Bridgestone, Kawasaki and Suzuki), there was really nothing for journalists to compare it to, but one word cropped up often – “vibration” – otherwise, reports were generally glowing in their praise. The kickstarter however, trapped a few as it had a tendency to fold inwards at the bottom of the swing and recoil smartly into the rider’s leg.

Chapter R-2

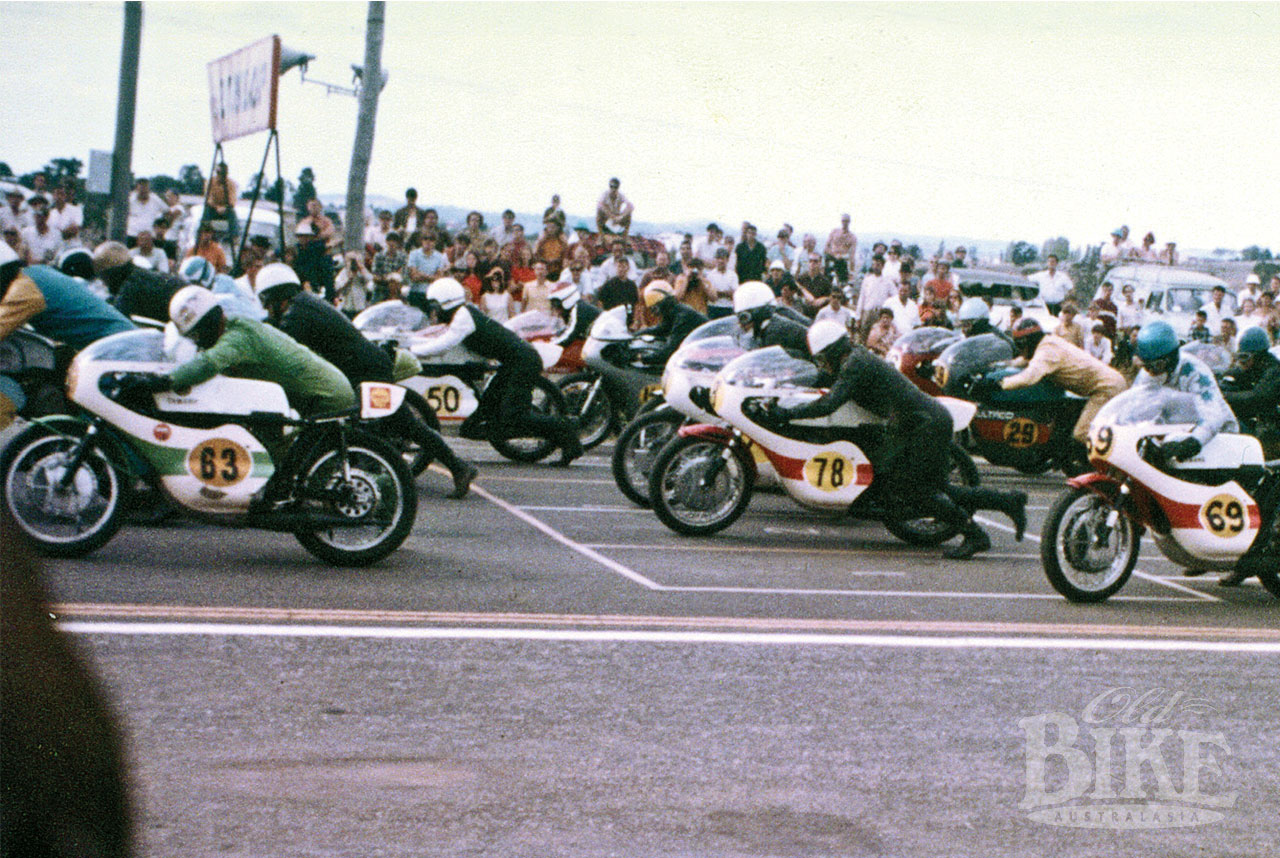

As good as the YR-1 was, Yamaha already had its next move worked out. By the end of 1968, the YR-2 was ready, and again the Japanese giant had Daytona in its sights. This time, the official team swelled to four entries which included multi world champion Phil Read, and Duff was again the fastest qualifier at a heady 147.347 mph – good enough for second behind Roger Reiman’s Harley. Ironically, Duff’s was the only Yamaha to fail to go the distance, but through no fault of the machine. The Canadian GP rider was simply too battered after crashing in the 250 race and had to pull out, while the others came home second (Yvon du Hamel), third (Art Baumann) and eleventh (Read). Only Cal Rayborn’s factory Harley-Davidson prevented the first-ever Japanese victory at America’s most important race.

Like the ’68 Daytona entries, the new YR-2 (still referred to in USA as the Grand Prix and also available as a high-pipe Street Scrambler, the YR-2C) sported new five-port barrels. The new porting system, with four transfers, gave more efficient and more complete combustion than two or three port engines. The YR-2’s transfer ports were spaced such that the upper edges of two were slightly higher in the cylinder than the others, providing what was referred to as a ‘second pulse’ mixture effect. The two ports located at the rear of the cylinder, alongside the inlet port, directed fresh mixture in such a way that waste gases were blown out, improving both cylinder head and spark plug cooling. On the new model, compression was lowered from 7.5:1 to 6.9:1. Of course, extra ports took more metal out of the cylinders, and to minimise distortion, Yamaha placed the through-bolts from the cylinder head to the crankcase near the port edges where hot spots occur. However the real advantage of the new porting was not in increased horsepower, which was only two more than the YR-1, but in flexibility, with a markedly better torque curve and much better low and mid range power.

Despite being fitted with a 14.4 litre fuel tank, the best test riders could manage was about 240 kilometres between fuel stops. Below the fuel tank and seat were two panels, the left covering the tool compartment and one of the air filters, and the right one hiding the other air filter and the oil tank with its filler cap. A clear plastic window displayed the oil level, with about two litres of oil consumed for every three fuel fill-ups.

Out on the road, the new engine behaved itself admirably around town, but when the power could be unleashed, 4,000 rpm was the magic mark. Once that point was reached, the YR-2 fairly howled away to the 7,500 red line, and a 3,500 rpm effective powerband was excellent for a two-stroke of the day. Unsurprisingly, the YR-2C, with its bulbous upswept exhaust pipes, scored poorly in the comfort stakes. Testers complained that the fat, hot pipes forced them to adopt a bow-legged position that was both ungainly and uncomfortable, while the high-rise handlebars pushed the rider into the wind and the cables obscured the instruments. The footrests were also placed differently on the Street Scrambler, causing bruises galore when kick starting. On the other hand, the standard YR-2 was awarded universal praise for comfort and practicality. Who needs a Street Scrambler anyway?

The 350 underwent a further refinement for 1969, becoming the YR-3. Yamaha had obviously worked hard on the powerplant, as the powerband was further widened from the YR-2, and vibration significantly reduced. Technically, the engine now revved to 8,000, but usable power fell away beyond 7,200. The most obvious change was the use of separate instruments to replace the old headlight-mounted combined unit, but the overall styling remained intact – it wasn’t time to ditch the needle-nosed fuel tank just yet, although the chrome-plated side panels were now colour-matched with the rest of the paint, which could be red, black, or a rather gaudy lime green.

By the time the Yamaha R5 was released in 1970, the original concept had been drastically modified styling-wise. The dated dart look was gone, replaced by a much more conservative look that was mirrored on the bigger XS four-stroke models. The R5 engine sported revised dimensions of 64 x 54mm (for 347cc), and the exhaust system was now a one-piece affair on each side, rather than slip-on mufflers and their associated tendency to weep goop at the joint. But the strength of the basic YR-1 engineering design lived on through the subsequent RD models (which grew to 400cc in 1977) and even to the water-cooled LC and RZ 350s. And of course, the TR and water-cooled TZ models totally dominated the race tracks, giving private owners worldwide fast, reliable machinery that delivered satisfaction as well as results. In fact, the basic RZ350 engine unit lives on as the motive power of the Banshee ATV four-wheeler – a fabulous innings and testament to the brilliance of the original design.

The Bathurst bombshell

Easter 1969 was the weekend when the Yamaha 350 really arrived in the eyes of the buying public. “King of the Mountain” Ron Toombs, a perennial winner on traditional AJS and Matchless singles, arrived in new lime green leathers and with a pair of brand new ‘Daytona’ Yamahas – a 250cc TD2 and a 350cc TR2. While the 250 suffered a gearbox failure, the 350 waltzed away with the Junior Grand Prix, Toombs winning by more than a minute after ten laps. The following week, the phones rang hot at Yamaha with top riders clamouring to get aboard the latest racers. It did sales of the road-going YR-2 no harm either. Twelve months later, the Bathurst grid was full of the new 350s, with Bryan Hindle winning both the 350cc Junior GP and the Unlimited – the first two stroke win in Bathurst’s premier category.

Local lovely

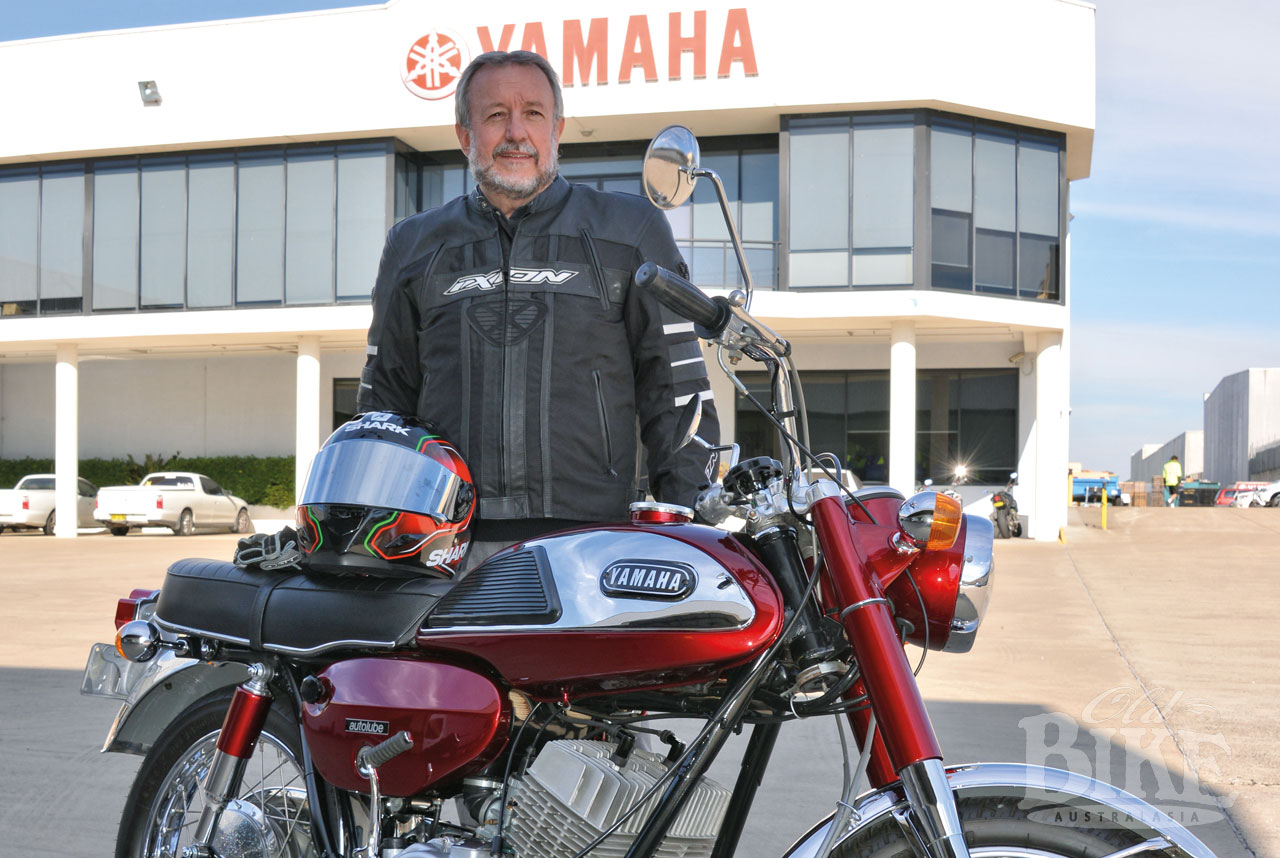

The subject of our photography is a 1968 YR-2 owned by Syd Darke, who is more than just a Yamaha enthusiast, he’s Admin Manger at Yamaha’s Australian headquarters in Sydney and also owns an RZ500 and an XS650. Syd’s YR-2 is an Australian-delivered bike, sold originally by Vic Lyons Motorcycles in Homebush on Parramatta Road. Syd has owned the YR-2 since 1970 and undertook a complete and meticulous restoration a few years ago. “Everything is original Yamaha except the tank badges, “ said Syd. “ There is still a surprising amount of original stuff available for these bikes; things like cables and engine parts are no problem. The mufflers are impossible to find, but luckily I have a few spare sets in very good condition, and the chrome tank panels are also rare. We restored the engine in the workshop here (at Yamaha, Sydney), including the crankcase paint and the fittings. It took a while to get the correct screws for the covers – which had been replaced by cap screws – but we eventually tracked those down.” Syd’s bike was displayed on the Yamaha stand at the 2013 Sydney Motorcycle Exhibition, where it drew many admirers over the three days of the show. Invariably, the conversation amongst on-lookers went something like, “I remember when Fred got one of these; blew all the Bonnevilles into the weeds, it did!”

Specifications: 1968 Yamaha YR-2

Engine: twin cylinder piston port two stroke

Bore x stroke: 61 x 59.6mm = 348cc

Compression ratio: 6.9:1

Carburation: 2 x 28mm Mikuni

Power: 36hp @ 7,500 rpm

Gearbox: 5 speed

Primary drive: Helical gear

Final drive: Chain

Lighting: 100 watt generator

Wheelbase: 1336 mm

Seat height: 800mm

Ground clearance: 145mm

Weight: (wet) 168kg

Top speed: 96 mph (158 km/h)

Standing ¼ mile: 14.7 seconds – 86 mph