Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook • Historical photos: John Ford

The Yamaha FZ750 broke new ground when it was released in 1985, and remains one of the most innovative designs of an era full of innovative design. Yamaha called this the Genesis engine, and it was too.

Yamaha have long been keen on experimentation with cylinder head design and the use of multiple valves. Although their first fours strokes – the XS1 and TX750 twins – used conventional 2-valve arrangements, the company was soon testing all sorts of different configurations with up to seven valves per cylinder. The latter was built in 1980 in prototype form as a liquid-cooled V-four code named 001A and designed for the 500cc GP class, but unlike Honda’s NR500 8-valve-per-cylinder with its oval pistons, the Yamaha used a conventional circular bore with four inlet and three exhaust valves. One of the inlet valves sat in the centre of the combustion chamber, with a spark plug on either side. Early tests showed that a major problem was having the flame-fronts from the two spark plugs colliding. It was designed to spin to 20,000 rpm, but the inherent problems – and the enormous production costs – spelled the end for the seven-valver, and Yamaha embarked on a six-valve (three inlet, three exhaust) version that apparently addressed many of the concerns. Well before it was race ready, advances in two stroke design, including by Yamaha itself, rendered the seven and six-valve four stroke uncompetitive.

But Yamaha was far from deterred with its determination to break the mould as far as combustion chamber design went. The engineers settled on five valves – three inlet and two exhaust – as the preferred option, and the first motorcycle to receive the fruits of this labour was the FZ750, released in 1985. Not that this was the first five-valve engine either – that honour belonged to Peugeot and went back to 1905! At the same time, a separate Yamaha effort (and one that consumed a colossal amount of resources) was going into the design and production of an engine to power Formula I cars, using the same five-valve layout. For the 1989 season, Yamaha struck a deal with the German Zakspeed team, which had considerable sponsorship (and just as well) from cigarette company West, but it was a disaster – the team qualifying only twice in 16 races. Red faced, Yamaha withdrew from F1 while a new V-12 engine was built for 1991 to be used by the Brabham team, but with only marginally better results. In eight years of F1 that included 116 starts, Yamaha-powered cars collected an embarrassingly small haul of just two podium finishes.

But back to the FZ750, which formed the vanguard for Yamaha’s high-performance motorcycle range for many years. With the valve mass spread over five instead of four, each valve weighed less, which may have been a factor in Yamaha’s claim that valve adjustment (bucket/shim clearance) was only required every 45,000 km. In a major break away from the old pent-roof combustion chamber and high-domed piston, the FZ used the narrow valve angle with waisted valves and flat top piston concept pioneered by Cosworth in their Formula 1 engines. In fact, the FZ pistons were slightly concave to provide clearance between the piston and the central spark plug electrode, yet still resulted in a compression ratio of 11.2:1. This design concentrated the spark in the centre of the piston and was important in achieving burning efficiency with the increasingly mandated unleaded fuel. The camshafts, which had to be removed for shim adjustment, were carried in a separate case to the cylinder head, which housed the valve gear.

The engine measured just 414mm across – narrower than the company’s 400-4 – with the alternator mounted on a jackshaft behind the cylinder block instead of on the end of the crankshaft. A novel approach to minimising the overall width was to use wet liners only at the hottest part of the block – in the middle. More fresh thinking appeared in the ignition department, with two coils attached to each side of the crankcases and triggered by grooves machined into the outer flywheel webs. When the groove passed the coil the magnetic field was broken, triggering a spark, which always came at exactly the same point, so ignition timing never varied. An ignition cut out prevented revs from rising above 11,800. Power was quoted as 102 hp at the crankshaft, but by the time it arrived at the rear wheel around 17 of those horses had gone astray.

Every test of the new model commented on the broad spread of power and the mid-range grunt – the engine pulling cleanly from as low as 2,000 rpm all the way to the red line at 9,500 rpm, by which time the FZ750 was doing 228 km/h in top (6th) gear. Another aspect that drew universal comment was the gearbox – frequently referred to as ‘sloppy’ with excessive transmission freeplay and a snatchy nature in the city due to a clutch with a very narrow take up.

Visually, the engine broke new ground, with the cylinders tilted forward at 45 degrees, and this created some unique design challenges. With the engine at such an angle, the bank of 34mm CV Mikuni carburettors ended up where the cylinder head would normally have been, with a near vertical straight path to the engine. It also meant a fuel pump was necessary, and that the air filter and airbox was located forward of this in a space behind the steering head. With the air intakes facing forwards directly into the air stream, rather than drawing from under the seat as was usual, a healthy supply of cool air was delivered to the airbox. To accommodate the top of the engine and the airbox, the fuel tank tapered from the front with the bulk of the liquid carried low and to the rear – not a bad thing in lowering the centre of gravity.

Ironically, news of the 5-valve FZ750 was greeted with scepticism in many journalistic circles; memories of the ill-fated TX750 twin with its Omni-Phase balancer and chronic oiling problems perhaps still fresh. To counter the negative response, Yamaha engineer Osamu Tamuru, the designer of the new engine that he had been working on since 1980, issued a number of press statements vigorously defending the design. He pointed out that the three inlet valves weighed half that of the Yamaha XJ750 and had less lift, resulting in much less wear. Yamaha also made much of their new 2,000cc V6 racing engine, designed for sports car use, which also employed 5-valve heads.

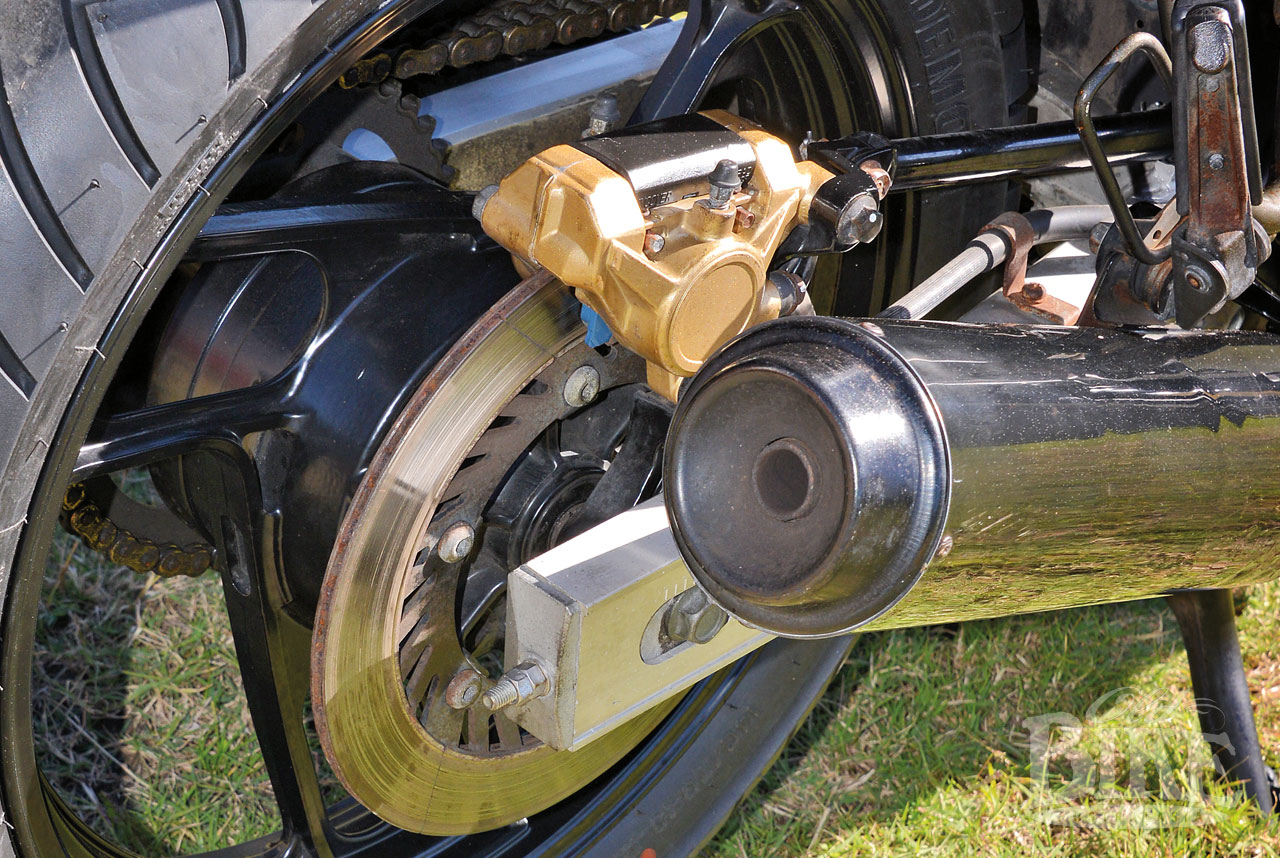

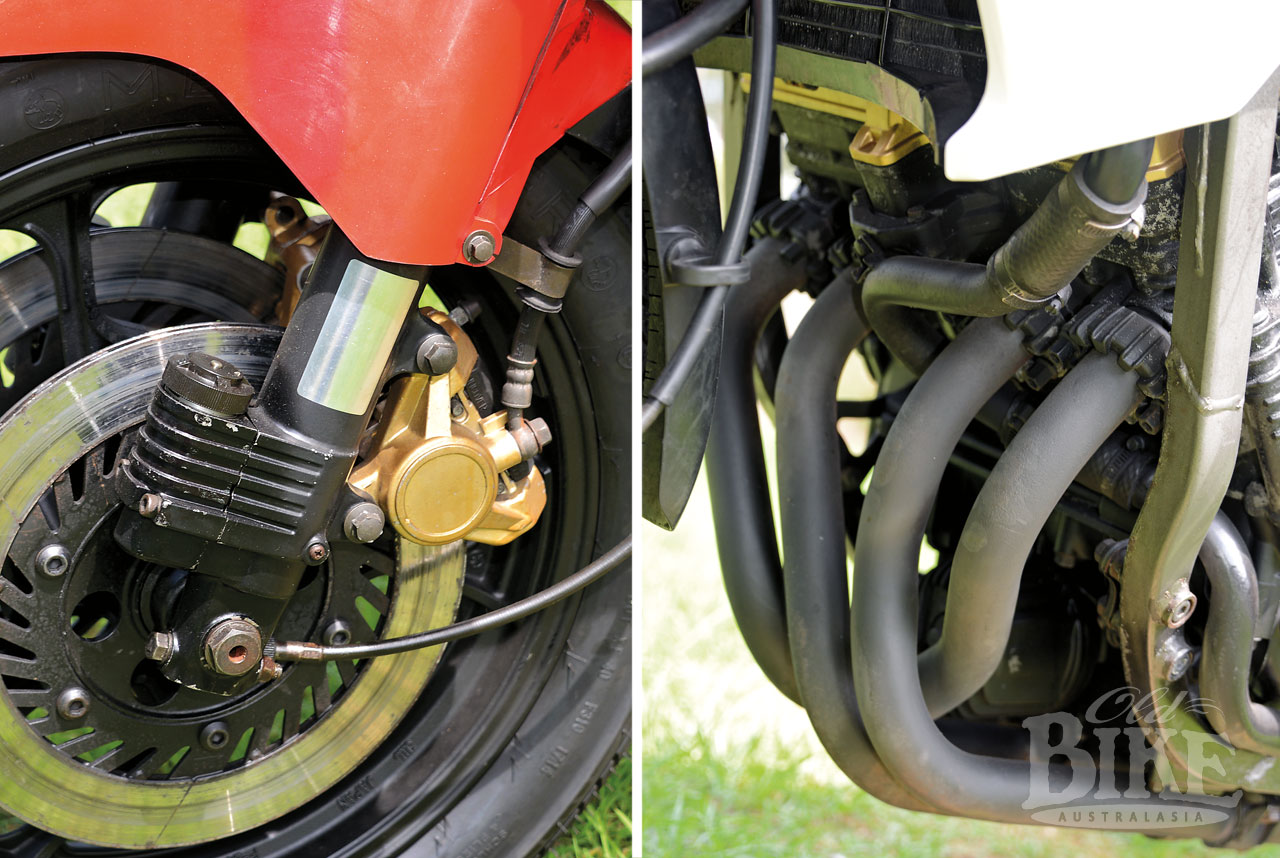

Chassis-wise, the FZ750 also broke new ground. With the slanting engine, it was a task to keep the wheelbase short enough, and on the FZ it ended up at 1485mm. The frame itself was based on the works OW60 500cc Grand Prix machine raced by Graeme Crosby in 1982, but made in rectangular section high tensile steel rather than aluminium. Steering angle of 25.5º with 94mm of trail was also GP-inspired, as was the use of a 16-inch front wheel. Front forks were air-assisted with compression damping increasing with the travel, while at the rear, a single shock with remotely adjustable spring preload and rebound damping, mounted vertically behind the engine, was used. Braking was by ventilated discs with twin piston callipers at both ends – the rear with the calliper underslung.

The instruments were virtually identical to those on the popular RZ Yamahas – big and easy to read, with automatic cancelling indicators a nice touch. Something that was rapidly disappearing from sport-styled bikes – a centrestand – was a standard fitment on the FZ. The choke control and the reserve fuel tank were set into the left side of the small fairing. Interestingly, Yamaha chose only to fit a half fairing, when its chief rival in the 750 class, the Suzuki GSX-R750, sported a full fairing, albeit a slab-sided rather ungainly one. Officially, there was no explanation, but most felt that Yamaha simply wanted to make the most of the unique engine design by placing it on full view, although a fully-faired model was offered as an option in USA. Significantly, the Suzuki tipped the scales a full 32 kg lighter than the Yamaha.

Public bow

The entire development process of the FZ750 was shrouded in intense secrecy, and when it appeared in public for the first time at the September 1984 Cologne Show it caught everyone by surprise. At this time, the emphasis was markedly swinging away from big bore superbikes back to the 750 class – fuelled by the rumoured imminent introduction of an official F.I.M. World Superbike Championship with a 750cc upper limit.

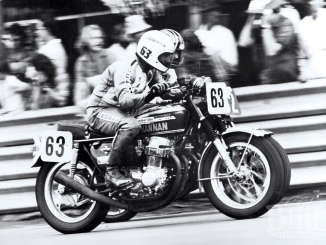

In Australasia, the hotbed for Production Racing in the world, news of the FZ750 was eagerly savoured by the competition fraternity. Its debut at Bathurst was hardly auspicious however, being comprehensively beaten by the Suzukis, which took the first three places in the 750 Production Race. A few weeks later at the Denso 500 at Winton, it was a different story, as the Yamahas’ big fuel tank and better fuel consumption came into play – the Yamaha Dealer Team pairing of Kevin Magee and Michael Dowson making only two stops to their opposition’s three.

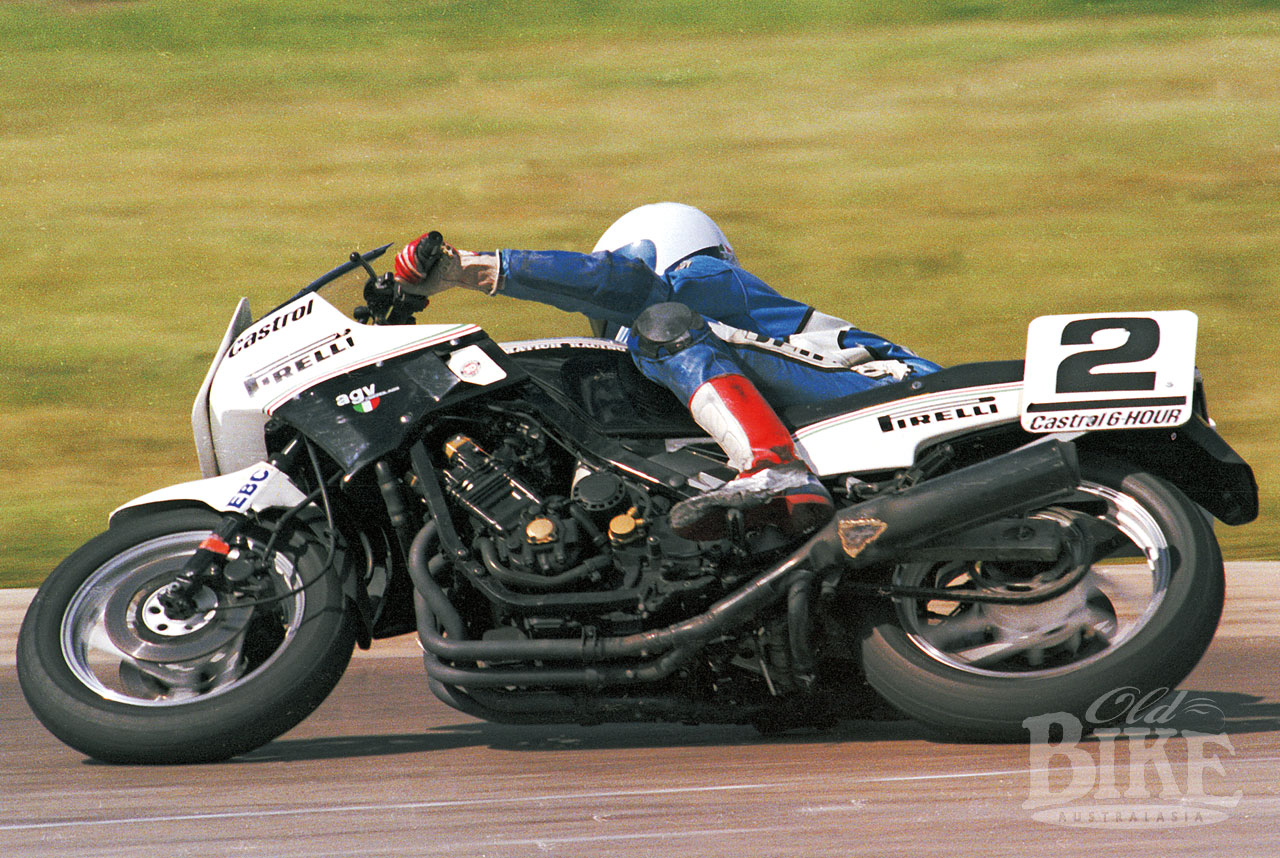

Yamaha’s chances for the all-important Castrol Six Hour Race at Oran Park looked good, but the fuel advantage was negated by the weather; the race being run at a much reduced pace in wet and gloomy conditions. Eleven teams opted to enter the FZ750, the same number as chose the GSXR-750. Dowson and Magee were again teamed on the Toshiba Yamaha Dealer team bike, with other fancied pairings coming from the Matich Racing bikes of Paul Feeney/Richard Scott and Glenn Taylor/Glenn Williams. In the race, Len Willing’s Kawasaki GPz900 and Magee’s FZ750 battled it out for the lead, but Magee’s co-rider Dowson dropped the model mid-race. Meanwhile Paul Feeney, riding with a broken ankle, was putting in a demon ride and came home the winner after Willing fell in the final ten minutes, even though both Feeney and co-rider Richard Scott slid off during the course of the race. Magee/Dowson capped a great day for Yamaha with third place.

A year down the track, the 1986 running of the Castrol Six Hour was all about the FZ750, with Magee and Dowson once again paired to come home with almost a lap advantage over the all-Kiwi Suzuki GSXR-750 ridden by Robert Holden and Brent Jones. FZ750s also filled third and fourth places. But racing is a fickle sport, and in 1987 there was not a single FZ750 to be seen at the Six Hour – the outright honours instead going to the new FZR1000, the latest and fastest version of the Yamaha five-valve story.

The FZ750 remained in production until 1991, but Yamaha persisted with its five-valve engine until 2006 in the form of the R1. Then in 2007, Yamaha joined all other major manufacturers in reverting to a four-valve head for the R1 and its other big four strokes. Why was five valves abandoned after all this time and development? There’s no official word – that’s progress for you, but manufacturing costs may well have had a lot to do with the decision.

Thanks to Old Gold Motorcycles of Londonderry, NSW for the opportunity to photograph both of the Yamaha FZ750s featured here.

Specifications: 1985 Yamaha FZ750

Engine: Water cooled four cylinder DOHC with 5 valves per cylinder.

Bore x stroke: 68.0 x 51.6 mm

Displacement: 749cc

Compression ratio: 11.2:1

Power: 102 hp (75.0 kW) @10,500 rpm

Torque: 78.5 Nm @ 8,000 rpm

Carburation: 4 x 34mm Mikuni Constant Velocity

Ignition: Transistorised battery/coil

Transmission: Gear primary drive, wet hydraulic clutch, six speed gearbox

Chassis: Rectangular section steel double cradle frame. Rectangular section alloy swinging arm.

Suspension: Front: Air assisted telescopic forks with progressive damping.

Rear: Rising rate monoshock system with continuous preload adjustment and nine rebound damping settings.

Brakes: Front: Twin 260mm ventilated discs with 2-piston callipers.

Rear: Single 260mm ventilated disc with 2-piston calliper.

Front tyre: 120/80 V16

Rear tyre: 130/80 V18.

Dry weight: 209kg

Seat height: 780mm

Wheelbase: 1485mm

Fuel capacity: 22 litres

Oil capacity: 3.5 litres

Performance: Standing 400m: 11.6 seconds/184 km/h

Zero to 100 km/h: 4.3 seconds

Maximum speed: 228 km/h

Price in Australia (1985): $5,590.00