From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 71 – first published in 2018.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

When Yamaha trotted out the RD350LC at the Paris Motorcycle Show in 1979, it was hailed as a miracle of modern engineering – a water-cooled twin cylinder two-stroke. But it wasn’t that revolutionary, after all, Scott built the same thing more than 50 years earlier.

It’s just that the ‘LC’ (the RD bit was a tilt to the now-defunct air-cooled RD range which had run up the white flag in the battle against ever-tougher emission laws) was such a complete package – the prodigal son of the racing TZ stable that had powered privateers and works riders alike since 1972, and without which, racing would have struggled to survive. Naturally, this point was not lost on legions of aspiring play racers, who saw the new RD350LC as the answer to their prayers – a weekday ride that could more than hold its own on the track on weekends. Soon, the grids were full of them.

As shown in Paris, the LC (Liquid Cooled) sported the Monoshock cantilever rear suspension originally conceived by the Belgian designer Lucien Tilkins, and which had graced the TZ range since the C model of 1975. The new roadster sported a single disc brake up front and a drum rear brake. It took a few months longer (until mid 1980) before the model began appearing in showrooms in Europe, in both 250cc and 350cc form, and with twin front discs, where they were eagerly snaffled up. But the 350 in particular was not without its problems, which began to show up immediately, especially under racing conditions. Vibration was the main culprit, causing exhaust pipes to crack and exhaust mounting studs to break off. There were also persistent mid-range performance issues – a combination of cylinder design and carburation settings, with both these original components replaced in the next model, along with a redesigned reed valve and a new design of oil pump. Getting the expansion chamber exhaust to stay in one piece took a little longer.

The 350 went on sale in Australia in 1981, priced at $2099, and continued until 1986, during which time it subtly evolved into the form of the bike featured on these pages. Again, it was US emission laws that sounded the death knell. In fact, the RZ350 (as it was sold in US) did not appear in the American market until 1983, and only then with the addition of a catalytic converter in each muffler of the exhaust system, and with no adjustment possible within the carburettors to deter home tuners from fiddling with the factory settings. When combined with oxygen, the converter essentially ignited the unburned fuel mixture that had passed through the engine. In California, measures went even further, with a third converter in the header pipes and a carbon canister inside the fuel tank to capture vapour before it reached the atmosphere.

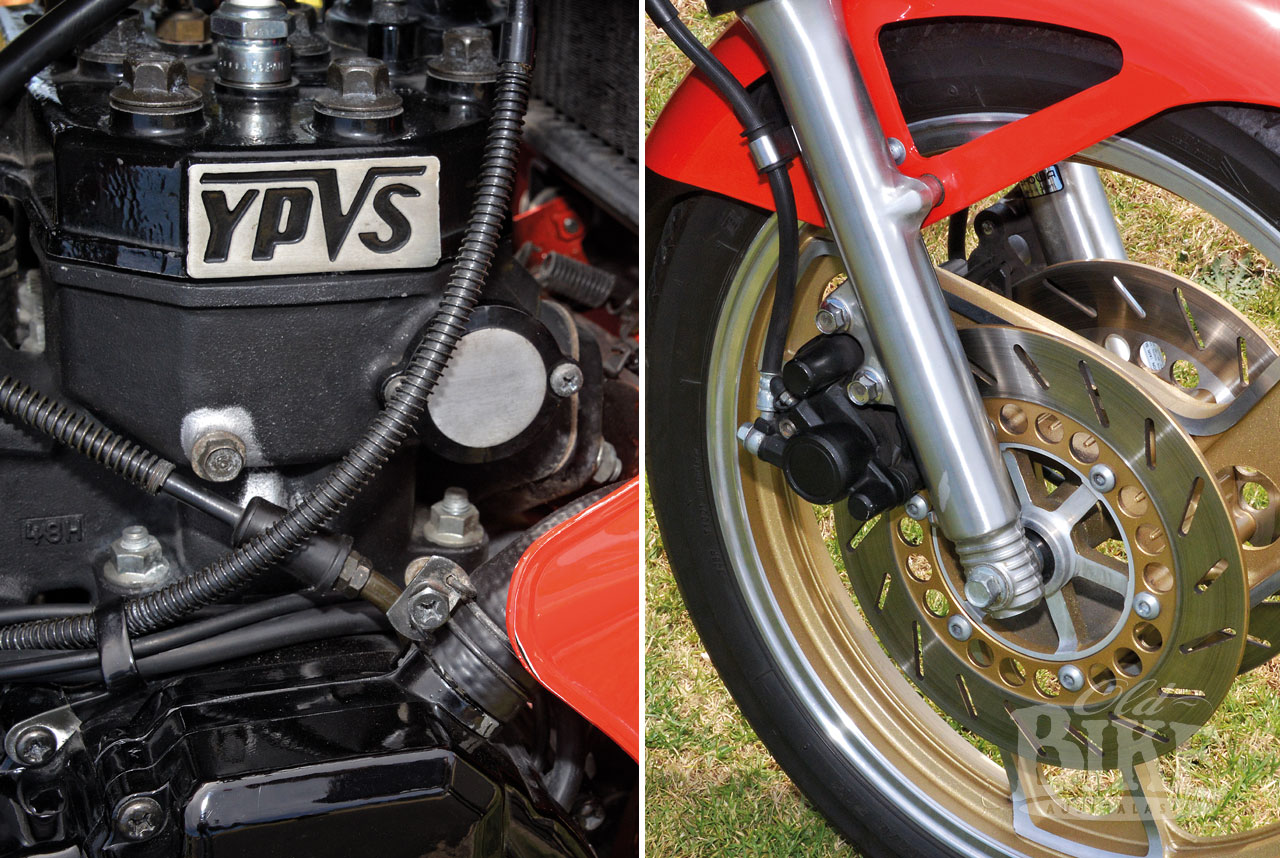

For the 1980 Grand Prix season, Kenny Roberts’ works YZR500 was fitted with what Yamaha called YPVS – Yamaha Power Valve System – a rotating cylinder fitted across the engine’s exhaust ports which was controlled electronically to vary the port timing and increase power and torque – and burn the mixture more completely. As revs increased, the engine’s CDI unit allowed the valve to rotate to a fully open position at maximum revs. With the Japanese ‘big four’ all producing road-going two strokes, variants of the YPVS system caught on rapidly from the time it first appeared on the revamped LC models in 1983.

The water-cooling of the RD/LC was a big selling point, with finer tolerances achieved as a result of a more stable engine temperature. The first model RD350LC was not fitted with a thermostat however, and in cold European weather, had trouble reaching an optimum operating temperature – a problem many riders address by the expedient of applying tape to the radiator to raise the temperature. In 1983 a thermostat was fitted, which cured the ailment.

Enter the RZ

Pretty much everyone expected the RD250/350LC to be the last gasp of the performance two stroke, but they were wrong. In 1983, Yamaha pulled a rabbit out of the hat with a substantially restyled version, now called the RZ350K in Australia to coincide with the model’s release in USA. Far from being a cosmetic makeover of the LC, the RZ was almost all-new in all the important areas; engine, frame, suspension, brakes. Beginning with the powerplant, the traditional 64mm x 54mm bore and stroke, which harked back to the R1/2/3 days of the mid-sixties, remained, but it had grown teeth, with power up from 34.5 kW (47hp) for the RD350LC to 43.5kW for the RZ350 (58.3hp) – that’s nearly 25%. The engine itself was new from the crankcase up, with the obvious addition of the YPVS system. Gaining this sort of power from a conventionally-ported engine would have meant sacrificing large chunks of bottom and mid-range performance, but the new system delivered tractability previously unknown in performance two strokes. The valve remained closed until around 3,500 rpm, and was fully opened by 6,000. Red line was at 10,000 rpm but the power dropped off sharply beyond 9,500. Maximum torque of 35.8Nm occurred at 8,500 rpm, and there was no trace of the LC’s notorious flat spot at 5,000 rpm – the RZ pulled strongly from 4,000 all the way to the red line. The RZ used separate seven-port barrels (like the racing TZ) (whereas the LC used a single block) with twin 26mm Mikuni carbs with reed valves.

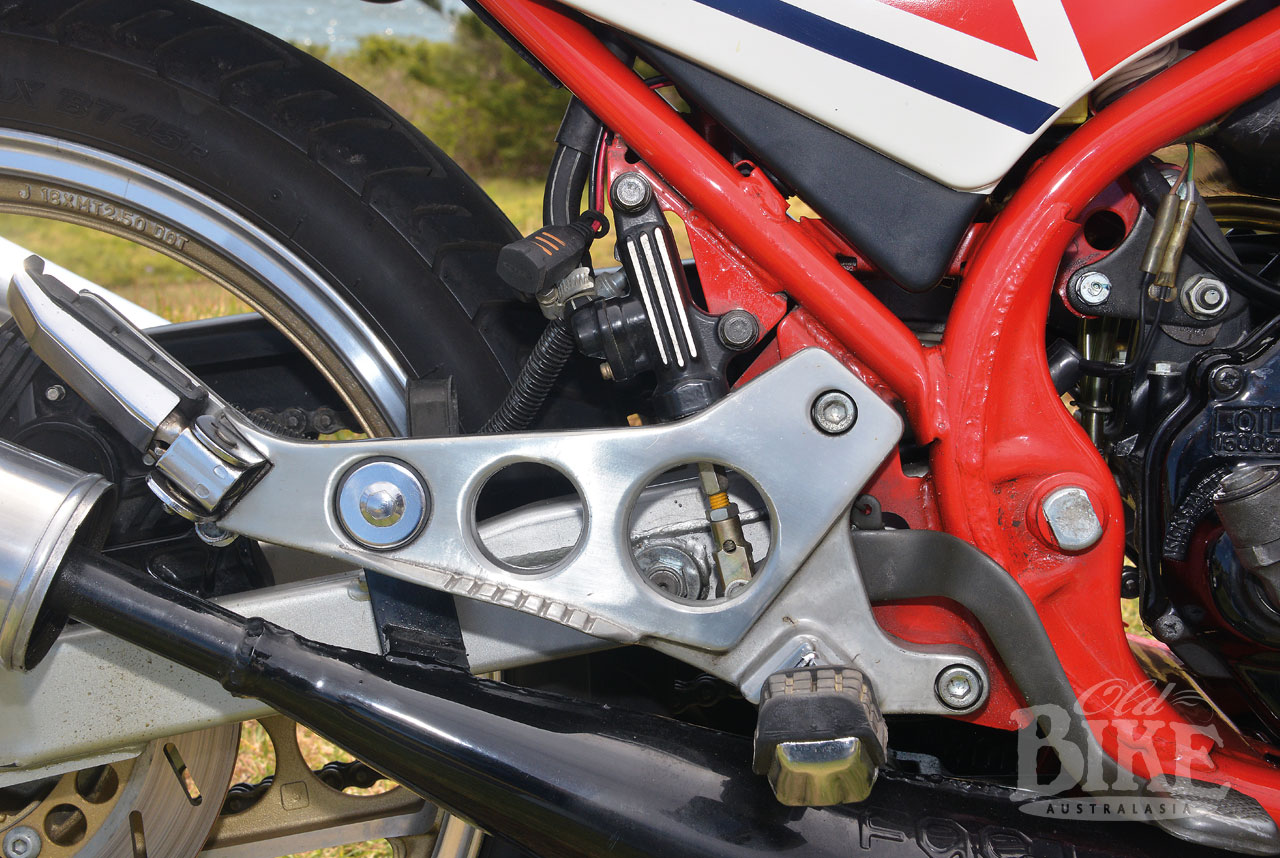

Chassis-wise, the RZ350 followed the basic LC design, but with larger diameter tubing and a wider cradle with more effective cross bracing and gusseting. The engine was rubber mounted at the front, reducing the vibes reaching the rider via the handlebars. Front forks carried air assistance (without a balance tube), but the gas-oil ‘Monocross’ single rear unit (located under tank via a rising rate linkage) was non-adjustable for damping, with five position spring preload adjustment. The spring tension was adjusted by removing the right side panel and turning a toothed-belt pulley with a spanner from the tool kit. The RZ frame used a steeper rake of 26 degrees (1 less than the LC) with less trail. To mollify the quick steering, the wheelbase grew from 1360mm to 1385. New style wheels (from the four cylinder XJ900) added a little more weight.

The RZ’s styling was also a far cry from the conservative LC. In keeping with the look of contemporary Grand Prix bikes, the fuel tank followed the line of the top frame tube towards the swinging arm pivot, with a small belly fairing enclosing the messy part of the engine (at least on a two stroke) and a bikini fairing shrouding the handlebars and controls.

End of the line

As the noose tightened on two strokes in the USA, the days of the RZs were numbered, and the axe fell at the end of 1985 when it became clear that impending tightening of restriction would make the RZ (and all other two stroke road bikes) history from 1986, at least in the key Californian market. But the story did not quite stop there. Yamaha shifted production to its subsidiary Yamaha Motor Da Amazonia in Brazil and continued production there from 1986 with what was officially termed the 1YH version. This used aluminium can mufflers attached to the expansion chambers, TZ style, with a half fairing. From 1988, the model, marketed again as the RD350LC, continued in production in Brazil with a full fairing, which in 1991 incorporated twin headlight. With ever-increasing anti-pollution restrictions sapping performance, production ceased in 1992.

Twice bitten

At the Shannon’s winter auction in Sydney, Steve Ashkenazi bought a 1985 model RZ350N. He didn’t mean to; it just happened that way. Steve was at the auction to sell his Kawasaki H2, which achieved a remarkable $33,500, so, flushed with cash and more than a little surprised, the very next lot to go under the hammer caught his attention. Back in his racing days, Steve progressed from a Suzuki X7 to an RD250LC in time for Bathurst in 1981, along with most of the field in the booming 250 Production class. “I reckon there would have been something like 60 of them (LCs) on the grid at Bathurst,” he recalls. It was the year of the RD250LC at Bathurst, when West Australian Michael Dowson led home Ashkenazi and Geoff McEwin (all on the new Yamahas) and in the process carved a staggering 9.3 seconds off his own lap record, set the year before on an RD250F. It was an emphatic demonstration of the quantum leap in performance made by the new water-cooled package.

“I really did not intend to buy anything at the auction,” says Steve, “In fact, quite the opposite as I have sold a few bikes recently to create some space. But this RZ350 was absolutely perfect, every nut and bolt looked like new, and it was pretty much identical to the RZ250 that I finished my racing with. It was meant to be: I even had a brand new rear luggage rack at home for this model! Through our shop (Macklin Motorcycles at Miranda in Sydney’s south) we sold heaps of LCs and RZs in the ‘eighties, but mainly 250s because of the ridiculous registration fees in NSW for bikes above 250cc. The 350 had about ten more horsepower, but even that wasn’t enough to justify paying triple the registration each year.”

In the saddle

The motorcycle that Steve purchased at auction is a 1985 US model, which has US-made exhaust pipes fitted with aluminium silencers, and without the catalytic converters. Nevertheless it runs beautifully, as I discovered one sunny day on the NSW South Coast when Steve gave me a chance to sample the bike on the glorious roads around Kiama. He told me that despite having the US-style carbs which have a linkage-type set up instead of individual cables to lift the slides, it carburates extremely well, and he wasn’t kidding. “When the RZs came out in Australia in 1983, they had none of the pollution stuff on them that the US models had to have, so they had huge horsepower,” said Steve.” The US exhaust pipes were extremely heavy with the catalytic converters.”

The RZ feels amazingly light and nimble – it brought back memories of my days on TZ350s – and it will take off with very little throttle. There’s absolutely none of the old two stroke bugbear where you chugged through the mid range and then hung on for dear life when it hit the powerband. The RZ pulls cleanly from around 4,000 rpm and just keeps on going. It has fantastic brakes, and with only 145kg to stop, they haul the bike down in no time flat. It’s great fun, particularly on these nearly deserted country roads, to play with the gearbox and keep the engine in its sweet spot at around 6,000 rpm.

The first decent corner I encountered was a disappointment, because I immediately realised I could have taken it at twice the speed with no dramas whatsoever. I remember watching the top exponents of the 250 Production class of the day as they rocketed through corners as if on rails, nose to tail, side by side, or both. This is a bike that cries out to be ridden hard, and it has heaps of ground clearance so the tyres (and your own bravery) are the limiting factor, yet it doesn’t complain if you just want to cruise along. Steve had arrived with his wife Wilma on the pillion, and both said the bike just buzzes along happily, with the sweet 6-speed gearbox doing its job perfectly. The seat is incredibly plush and comfortable, particularly for a bike with a sporty nature, and although the footrests and foot controls are rear set, the riding position does not place too much weight on your wrists – it’s just right.

It takes you back when you consider this bike is 32 years old, and it also makes you wonder what the RZ350 would have achieved with further development. After all, Grand Prix 250s were nudging 100 horsepower in the early ‘nineties, so a 350, even a road going one, would have to have had around that much power on hand. What a tantalising prospect.

Yamaha RZ350 – Specifications

Engine Parallel twin two stroke with reed valve induction and YPVS power valve.

Bore x stroke 64mm x 54mm

Capacity 347cc.

Compression ratio 6.0:1

Transmission 6 speed gearbox with gear primary drive.

Power 59.1PS at 9,000 rpm

Torque 35.8Nm at 8,500 rpm.

Top speed 185 km/h.

Induction 2 x VM26 Mikuni carbs.

Frame Full twin loop tubular steel. Rectangular section swinging arm.

Front suspension Telescopic forks with air caps.

Rear suspension Yamaha Monoshock

Brakes Front: twin slotted Discs, Rear: single slotted disc.

Tyres Front: 90/90-18 H, Rear: 11/80-18H.

Wheelbase 1385mm

Seat height 800mm

Dry weight 145kg

Price in Australia 1983 $2549.00