The trail to England had been blazed comprehensively by aspiring Australian and New Zealand road racers and speedway riders since the mid 1920s, but the same was not the case for the relatively new (mainly post-war) forms of off-road competition, namely scrambling, or as the continentals referred to it, motocross.

When Tim Gibbes set off from his adopted home of Adelaide, bound for England in 1955 to check out the scrambles scene, only one man had preceded him, Victorian Les Sheehan two years earlier. Sheehan found a place in the factory AJS team, and as well as scrambles, competed in the 1954 International Six Days Trial in Wales, winning a Silver Medal.

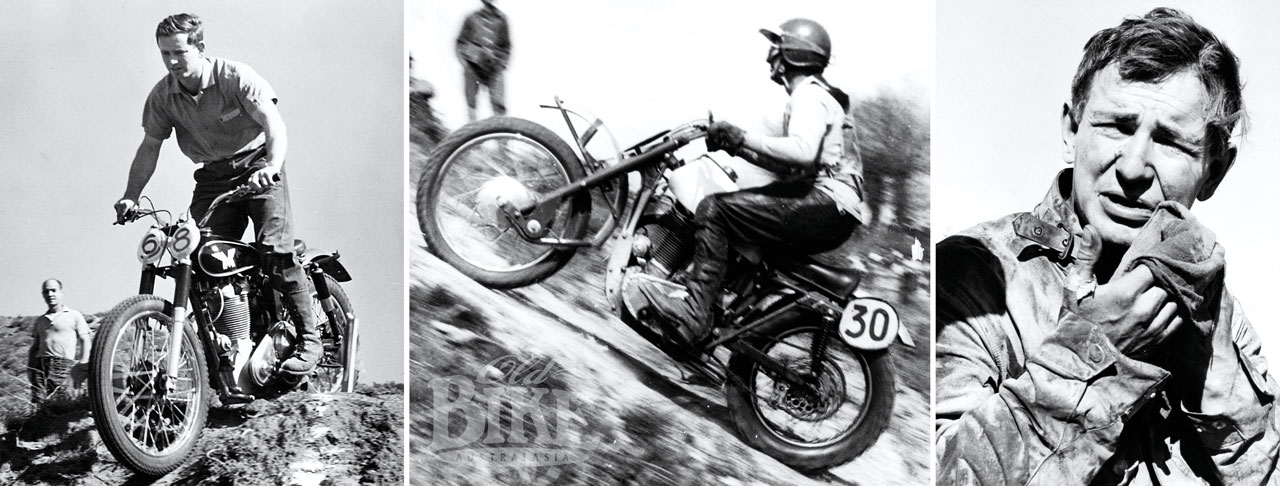

Educated at Urrbrae Agricultural School in Adelaide, Tim delighted in pulling apart old vehicles and driving tractors and trucks as part of the curriculum. After leaving school, he worked on farms on Eyre and York Peninsula, bashing around on an ancient Sloper BSA (with the frame of an outfit attached) hunting rabbits and kangaroos. His first motorcycle was a New Imperial with a side-valve JAP engine, but it was a purchase that horrified his parents. “It soon became obvious that motorcycling was not going to be compatible with my family,” he recalls. Nevertheless, Tim managed to compete in many local events like the punishing South Australian 24 Hour Trail and the one-off Redex Trail of 1954, where he rode a B31 BSA, before tossing in his job with Allis Chalmers and booking his berth on a boat to England for the sum of £72. It was a brave move, arriving just before the British winter of 1955.

“I sailed through the Suez Canal, where I bought a camera and a portable typewriter – I am not sure why – and when I arrived in England I went to AMC (Associated Motor Cycles) in London and got a job through the English winter testing bikes. I’d do 300 miles per day, 150 in the morning and 150 in the afternoon. It was good for me because I was doing a lot of riding and seeing a lot of the country. There was a set route – I was supposed to go down the A2 and back up the A20, but you would have found me halfway up to Scotland on some days and down near Devon on others. At the time, AMC had their singles range and 500 and 600 twins. The 600s twins were good because if the weather was really nasty or there was a thick London smog, you could blow them up in no time – the crankshaft used to break real quick. They were also developing the 250 AMC two-stroke, the radial fin motor used in Francis Barnetts, and later the unit-construction 4-stroke 250s – they were pretty quick to blow up too!”

To further his off-road ambitions, Tim was fortunate that trials ace Gordon Jackson, an AMC contracted trials rider, had his family’s farm not far from the AMC works. “It had been bombed quite heavily during the war and had craters everywhere. Gordon and his trials mates used to push me (on a bike) into a bomb crater and tell me to get myself out. It was great for learning throttle control and grip. “ Tim bought an ex-factory 500 Matchless scrambler and a 350 Matchless trials model, and rode both in scrambles and trials. It was in the Welsh Three Day Trial of 1956 that his 350cc class-winning performance impressed the AMC factory, because they offered him a place in the official team for the International Six Days Trial at Garmisch-Partenkirchen in West Germany. The result was a Gold Medal – the first ever won by an Australian. “I was now a contracted rider for AMC, but the contract was not in writing, no fees, and really was, “Here’s a bike, you go and uplift from the seconds around the factory, the spares you need”, but it didn’t do me much good for the 1957 ISDT in Northern Bohemia (Czechoslovakia). The British factories decided not to support the event, so I needed a machine. Before I left Australia I had ridden for A.G. Healing, the Jawa importer for South Australia, and somehow I ended up with a Jawa for that (ISDT) event.” It was history in the making, because with fellow Aussies John Rock, Roy East and Les Fisher, who all had connections with Jawa/CZ from the Australian end, an unofficial Australian team was formed – unofficial because Australia was not aligned with the FIM and riders used British ACU licences. The troubles started well before the event when the promised machinery failed to eventuate – just two 250 Jawas, which were basically roadsters with off-road tyres, braced handlebars and slightly raised mufflers, and a 175cc CZ – three bikes for four riders. The four names went into a hat and Roy’s failed to come out, so he was made Team Manager, which may have been a lucky break as the event was run in the most diabolical weather conditions of non-stop freezing rain and oceans of mud. Gibbes and Rock collected bronze medals, while Fisher’s CZ repeatedly threw its rear chain and eventually forced him out. Virtually every part on the bikes was marked, and Rock was forced to ride with his front mudguard strapped to his back for five of the six days. Tim recalls it as the worst weather conditions he had ever ridden in.

The Bohemian episode was not just wet and miserable for Tim, it cost him his AMC factory ride and his job as a road tester. “AMC was annoyed about the Jawa ride and gave me the sack, so I took a job with Ariel up in the Midlands. It was like moving back a century. I bought a 350 DBD32 Gold Star BSA, and Ariel gave me a 500 HT scrambler, to which I secretly added BSA fork internals. I’d come off an AMC putting out about 42 horsepower, onto an Ariel that at best – with your eyes watering – would have had 32. The only good thing about them was that you could hold the throttle against the stop. At the famous Hawkstone Park, which is not for the faint hearted, it was good for me because I could hold it against the stop the whole way around. I actually beat (twice world 500 champion) Jeff Smith in a series there – I was second and he was third.

“As well as racing, I was working at Ariels developing the Arrow and about that time in England the smog was really thick – you couldn’t see a metre in front of you. On those sorts of days they would leave the Arrows inside and give me a Square Four to test. I said to them, ‘I suppose you’re trying to kill me’ and Clive Bennett, who was in charge of Experimental and Competitions Shops said, ‘Yes, actually we are. We don’t really want you around here.’ I had my answer to that when I used to take a Square Four out. First I would knock it against the kerbs to knock the mufflers off, then I’d get 100 miles or so down the road and put it in second gear and just screw it. They didn’t drop anything but the valves would stick down. So I’d ring the factory and say ‘The bike’s broken and I don’t know what’s wrong with it, so would you come and get me.’ They would send someone down with a sidecar to pick me up but I wouldn’t let the guy ride me back on the sidecar, I make him sit on the back and they got pretty sick and very scared.”

Tim’s stint at Ariel included the 1958 ISDT in Germany, where he replaced Sammy Miller in the British Trophy Team after the Irishman had a nervous attack on the morning of the event that left him unconscious. Tim collected his second gold medal.

The employment at Ariel lasted one year, when AMC forgave and forgot and invited Tim back into the fold at Plumstead. First, though, was a trip home towards the end of 1958. “I took the Gold Star, which I had in Clubman trim because I used to do a bit of road racing in England and in Europe at places like Mettet in Belgium and behind the Iron Curtain on cobblestone roads – everywhere really because if you could get a feed twice a day it was better than once a day. I went back to Adelaide and I got a call from Roy East who said he and Les Fisher were going to ride at a road race at Wagga Wagga (Kapooka Army Camp). I didn’t know exactly what day it was on so I bought myself a Morris Oxford pick up and jammed the Gold Star, a 125 Tilbrook, and a borrowed Triumph Tiger Cub into the back and set off. Somewhere between Adelaide and Broken Hill a wheel fell off, and kept falling off all night until I found a farm with an arc welder and welded it on. By that stage I was having to drive through the day instead of travelling at night and it was so hot the big ends went. So I cut the leather tongues out of my shoes and relined the big ends with those – one of several similar roadside operations in various parts of the world. Eventually I got to Wagga and they said, “Where have you been, the races were yesterday!”

After few more local races, including Victoria Park at Ballarat where Tim and Alan Wallis finished 5th and 4th respectively on the Tilbrooks, Tim sold the Gold Star to Newcastle rider Jack Pringle and sailed again for England. AMC provided a 500 scrambler for him to use in Europe on the condition he came back to England for the important trade-supported scrambles. “Quite often I would be in the south of France and have to drive all night to get to the UK event. I had a factory bike but you needed to sort out what spares you needed well in advance because you’d be away for long periods. I used to live mainly in France, very much a loner, sleeping under the stars – totally air conditioned! Tim stayed with AMC until 1963 in the ISDT, but built his own bike for European motocross, a 500cc Matchless motor shoehorned into a 250cc Greeves chassis. By this time his ISDT Gold Medal tally was up to six, with one bronze on the Jawa and one DNF, in Czechosovakia. “The front fork yoke broke on the AJS – the ground was very hard and rocky and I must have been going too hard. I had a spare rear chain with me so I wrapped this around the fork yokes but it was basically uncontrollable and I had to pull out.”

During the 1960 season, Tim teamed up with New Zealand scrambler Ken Cleghorn, and married Ken’s sister Joan in 1961. By 1963 it was time to quit Europe to settle in Joan’s home town of Palmerston North and the newly-weds left on the first-ever Japan Airlines flight between London and Tokyo. Tim had arranged with a car and a motorcycle magazine to cover the Tokyo Motor Show, and it was at this event that he met representatives of the Motor Cycle Federation of All Japan, an amateur federation, but at the time, very much larger than the MFJ. “I got involved with the MCFAJ quite strongly. Their secretary general got me to all 12 Japanese motorcycle- producing factories, and some smaller ones, to give talks on off-road bikes. They had heard of street-scramblers but because they operated in a concrete jungle they didn’t know what motocross was. I used to go back there regularly until 1970. The MCFAJ would fly me from New Zealand to Japan to conduct trials and motocross schools. First off I took a Greeves which was a disaster because I needed a set of flywheels, which Greeves sent but they arrived only the night before I was to leave for Japan. I worked all night to fit them but didn’t start it and when I got there I discovered they had sent me a set of 197cc flywheels – for a 250! Of course the piston was halfway down the barrel so it would run but had no power, but I couldn’t change the wheels because the factories kept grabbing the bike and shipping it around – I went to every factory except Honda, who didn’t want to know. They would have a table with 20 or so engineers, each one with a specific area of responsibility – footrest, front brake, spokes and so on. No-one spoke English and we would start at 5am and go through the night until about 1 in the morning. It was all cloak and dagger because none of the factories knew I was going from one to the other. Out of this came some good bikes but it was hard work. The Japanese couldn’t work out if you had a 250 twin cylinder 2-stroke as wide asa Mack truck with 42 horsepower why you couldn’t win a world championship against something with 25 horsepower. Suzuki had just built their first motocrosser and sent a Japanese rider to Europe with it. The poor guy told me he felt the same frustrations. He said “I know exactly the trouble you’re in because I have just spent a whole season in Europe with the Suzuki breaking down and people looking at me and taking photos!”

There was another aspect to Tim’s international career – the two European winters he spent in USA, riding for the Matchless distributor (then named Matchless Indian) in desert races and what they called TT Scrambles – flat tracks, often inside stadiums, sometimes with a slight rise or jump. In 1960 he was joined by Roy East, who had the misfortune to break his leg when the front forks of his machine broke. “Roy was taken by ambulance to hospital. They laid him on slab and said before they would do anything they wanted $300. We had no dough so we went back to the scramble and took the hat around the riders and the hospital agreed to set the plaster. I had a Chev wagon and we came back the next day and they said they needed another $300 for Roy to stay another night, so when it got dark I backed the Chev up to the window and Roy crawled out. The only solution was to get back to the free medical in UK and it was getting time to get back to England anyway so we flew back, which included getting a helicopter between the domestic and International airports in New York city.”

Tim became good friends with ‘Bud’ Ekins, who had a motorcycle business in Hollywood and was a very talented desert racer. As well as helping Bud out when he came to Europe to ride in the ISDTs, Gibbes and Ekins found work as stunt riders on the set of the 1962 film, The Great Escape, which was shot in Germany. Gibbes stayed with Bud in USA and used his shop as a work base. The biggest desert race of the time was the Big Bear Run, which attracted around 1200 starters, and Bud and Tim were first and second when Bud’s Triumph blew a gearbox. Tim took over in the lead but, not knowing the route-marking system, took a wrong turn which cost him the race. The following year he was determined to make amends and took his place with more than a thousand others in a line across the desert, waiting for the smoke bomb to signal the start of the race. “Then (before the smoke bomb) someone took off and next thing everyone else did, it was a shambles. We got around the first loop – it was a cloverleaf track from a central point – and it was such a mess they just cancelled the event. I think this was the last Big Bear.”

Settled in Palmerson North, Gibbes opened his own motorcycle business, selling Honda and Yamaha, and importing Husqvarna and Bultaco. In the 20 years of operation before the business was sold in 1984, 10,000 motorcycles were sold. Over this period he had also been involved with coordinating New Zealand, and Australian international motocross teams to Europe, Australia and New Zealand and served on the executive for Motorcycling New Zealand. Then in 1995 he began to organise the Suzuki Road Race Series, which grew into NZ’s biggest such event. One aspect of the organization seemed to need some sorting out – the lap scoring. “With races graded by lap times rather than by class, everyone was lapping within 2 seconds of each other and manual lap scoring was a nightmare, so I started to think what could be done with a transponder system. I tried to design my own using things like garage door openers, but eventually ended up using the Dutch AMB system. Then the car people heard about it and got me to do some car events. Since 2001 Joan and I have been everywhere doing both car and bike events. Now I do the cars and Joan does the bikes – we pass each other on the roads going to different meetings! It’s a whole new interest for me. I had to learn about computers, electronics, wired and wireless networking, and I really enjoy the challenge.”

Clearly, a challenge is something that Tim Gibbes has always enjoyed and has no intentions of giving up. It’s just that he doesn‘t need to sleep under the stars anymore, and gets more than one meal a day.

International Six Days Trial

Long distance trials are almost as old as the motorcycle itself. When the Auto Cycle Club was set up as an offshoot of the Automobile Club of GB and Ireland in 1903, one of its first actions was to organise a 1000-mile competitive trial. By the time the ACC was reorganised as the Auto Cycle Union (ACU) in 1908, the event had become known as the Six Days Reliability Trial and in 1913 it included an international element.

However, it was in the Twenties that the ISDT tradition really started, with the event staged by a different host nation each year. An exception was 1929, when the trial was held in the Alps and took in several countries. The basis of competition was to maintain set average speeds over a variety of terrain on a production motorcycle while keeping it in good order and without recourse to major repairs, spare parts or outside assistance. National teams competed for the major trophies on machines closely related to catalogued models, while individual riders were awarded medals for outstanding performances. British teams won the major award six times in a row, but in the Thirties Germany came to the fore to win twice.

The 1939 ISDT was held in Salzburg in the last days before World War two was declared. British competitors had to make a mad dash for the cross-Channel ferry home and no official results were approved.

Resuming in 1949, the trial was won by the host nation Czechoslovakia who took both the Trophy and Vase team awards. In 1948 British teams won both awards in San Remo, Italy and the UK hosted the trial in Wales for the next two years. It returned again in 1961 and in 1965 it was held on the Isle of Man for the first time.

Competition grew ever tougher, especially as Eastern Bloc countries entered well-drilled military teams, often riding light and nimble small-capacity machines.

The first ISDT held outside Europe was the 1973 event in Massachusetts, USA. Despite problems afflicting the British industry, Triumph prepared machines for UK and US riders. The British team was only narrowly beaten by Czechoslovakia and all its members bar one collected Gold Medals.

The last ISDT was held in 1980. Its successor is the International Six Days Enduro, contested by more specialised machinery and now including a women’s trophy. The 2007 event in Chile won by Italy was the first to include an earthquake among its hazards!

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Merv Whitelaw. Tim Gibbes archives.