Story: Alan Cathcart • Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura, Ross Hannan, Dick Darby, Chris Sim, OBA Archives

It’s highly unlikely that any other Classic era road racer has been replicated as frequently around the world as the twin-cylinder Drixton Honda. Created back in 1968 by Aussie Terry Dennehy and his mechanic mate Ralph Hannan to go 500GP racing affordably, this privateer concoction entailed their tuning up a stretched twin-cylinder CB450 Honda motor, and wrapping it in a frame made in Italy by Swiss man-of-many-parts, Othmar ‘Marly’ Drixl. A rider himself of no mean ability, Marly is best remembered for the small series of Drixton frames which he produced in the late 1960s for Aermacchi and Honda engines, originally under the aegis of the then British Aermacchi importer and former Norton works rider, the late Syd Lawton.

“Marly was one of those people who always made it his business to know what was going on,” recalled Lawton in an interview we made together before he passed away in 1997. “But in spite of this, and the fact that he always seemed to have some deal or other on the go, he was also just about permanently broke! I first came across him in 1964, not long after I began importing Aermacchis. Marly was working on the production line at their factory, and living with his wife and young child in a van parked up by the nearby lake.”

After their meeting Drixl raced quite a bit in Britain on an Aermacchi with some help from Lawton, and it was on one of his visits to the UK in the mid-‘60s that the two discussed a problem which had recently arisen. The manufacturers of Avon tyres had pulled out of racing, and the new triangular Dunlop tyres proved quite unsuited to the already fingertip handling of the standard Aermacchi frame. “Marly said he could make an Aermacchi chassis that would be much better suited to the Dunlops,” says Lawton, “if only I would provide him with the necessary materials. Marly wasn’t dishonest, but cash burnt a hole in his pocket, which was why he was usually broke. Anyway, I staked him enough to build the first three frames, which he did in the Baroni workshop in Milan, then he sold them through me as Drixtons – standing for Drixl and Lawton chassis.”

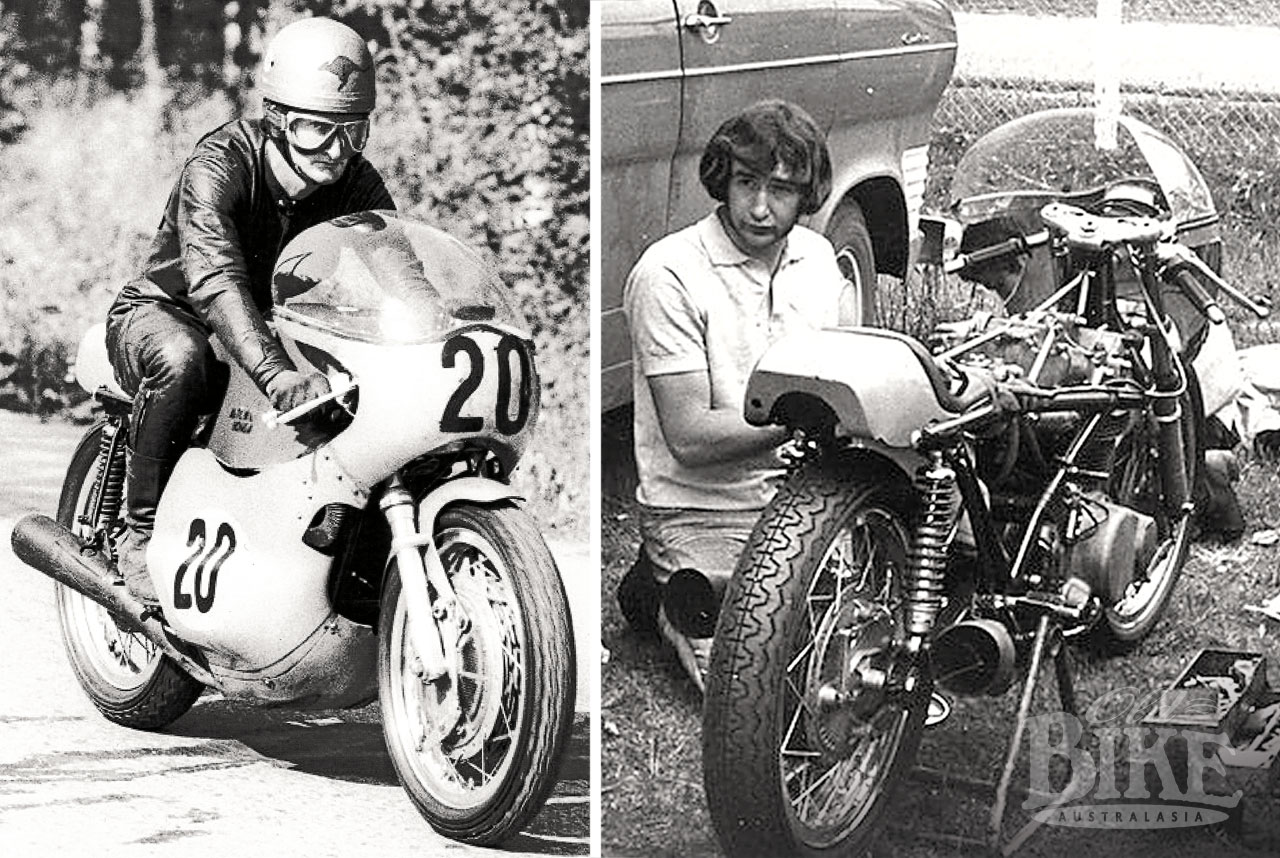

Around 25 Drixton Aermacchi frames were built from 1965-69, some of which were snapped up by leading GP privateers such as John Hartle and Kel Carruthers, who finished third in the 1968 350cc World Championship on such a bike behind the MV Agusta and Benelli fours. Not bad for a pushrod single – but the assured handling of the Drixton frame was a key element in this success. Many of the Drixton Aermacchis built back then are still around today, thanks perhaps to their sturdy but somewhat agricultural construction. One of Drixl’s customers for the Drixton Aermacchi frame had been Terry Dennehy, who was based in Milan, not far from the Aermacchi factory. In Easter 1964 at the age of 19, he’d quite remarkably won his first ever motorcycle race by riding his standard Honda CB72 road bike to victory on the challenging Bathurst circuit in the newly-instigated Lightweight Production class, after which he and his mechanic mate Ralph Hannan, both from Sydney, took up the racing game seriously. The Honda was turned into an Open-class 350cc racer which took Dennehy to second place in the 1966 Australian TT at Bathurst, then in 500cc guise led the following year’s Phillip Island race, until the primary chain broke and he crashed. Time for the two 22-year olds to join the exodus of Aussie up-and-comers to Europe, and become part of the Continental Circus.

For his first season in Europe Dennehy raced a 125cc Honda CR93 that proved to be a good earner, delivering many wins in non-championship races in between periodic crankshaft failures. Terry also bought a, but didn’t get on with it as well as the Honda, so swapped it for a Drixton frame, which is how he came into contact with Marly Drixl. Ralph and Terry initially spent the winter of 1967/68 in England, but hated the weather, so they headed for Milan where they drew up plans with Marly for a 500GP racer powered by a Honda CB450 engine set in a Drixton frame – with Honda’s recent withdrawal from GP racing there was plenty of space for privateers to make a good living by battling to be best of the rest behind Ago’s solitary works MV Agusta.

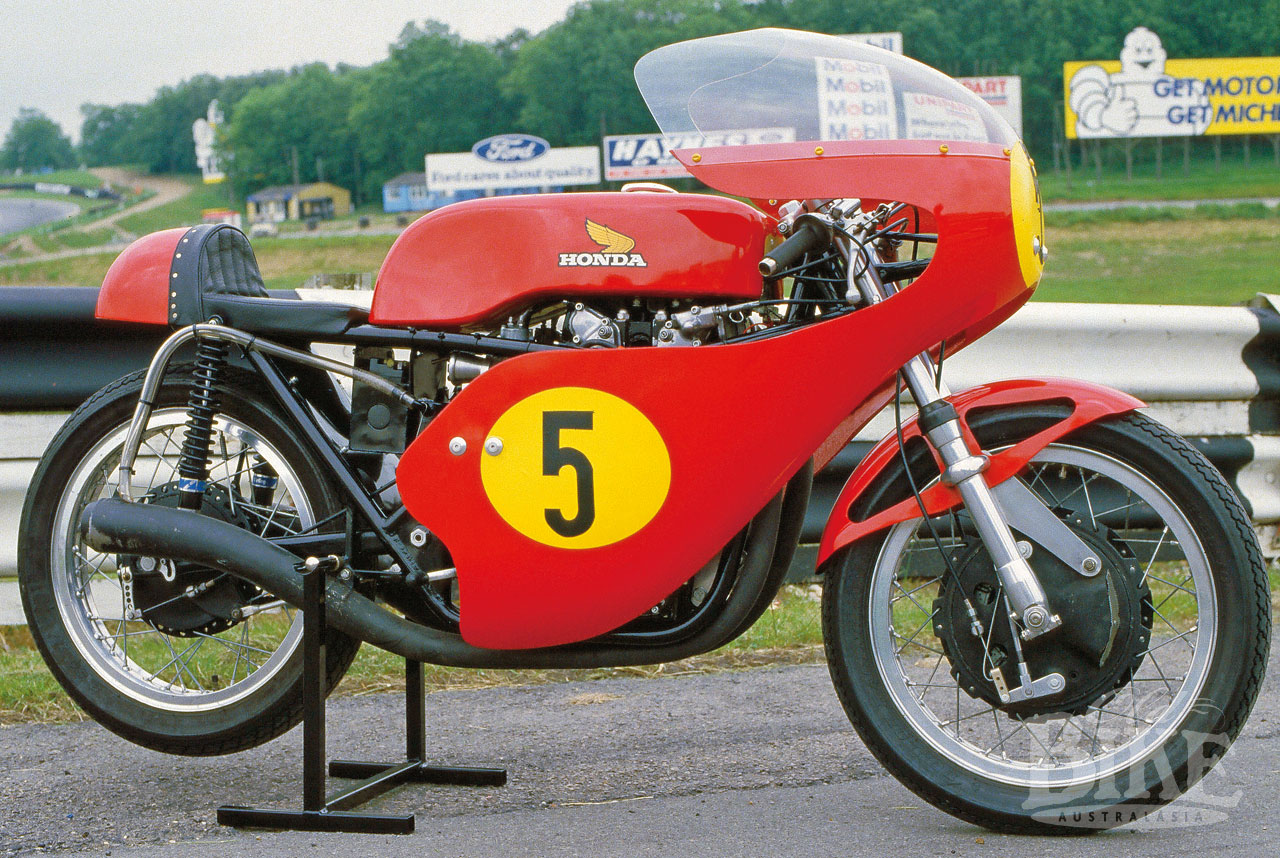

The DOHC CB450 Honda parallel-twin roadster had first appeared in 1965, initially with a four-speed gearbox, and effectively ushered in the modern era of high-performance Japanese streetbikes. With its oversquare 70 x 57.8mm dimensions delivering 43bhp at 8,500rpm, the 445cc ‘Black Bomber’s’ lively performance brought it heaps of success in production racing, and it seemed an ideal basis for an inexpensive road racer to rival the Seeley G50s and Manx Nortons then forming the backbone of international grids, with ready availability of affordable spares a key advantage for the cost-conscious Aussies. So Drixl designed a chassis and fuel tank for the engine in 1967, and built up the first prototype over that winter, completing it early in 1968, although thanks to lack of money and the difficulty for Terry as a 500GP class novice in obtaining entries and start money, it wasn’t actually raced until the following season, by which time Honda had produced an uprated version of the street model with a five-speed gearbox.

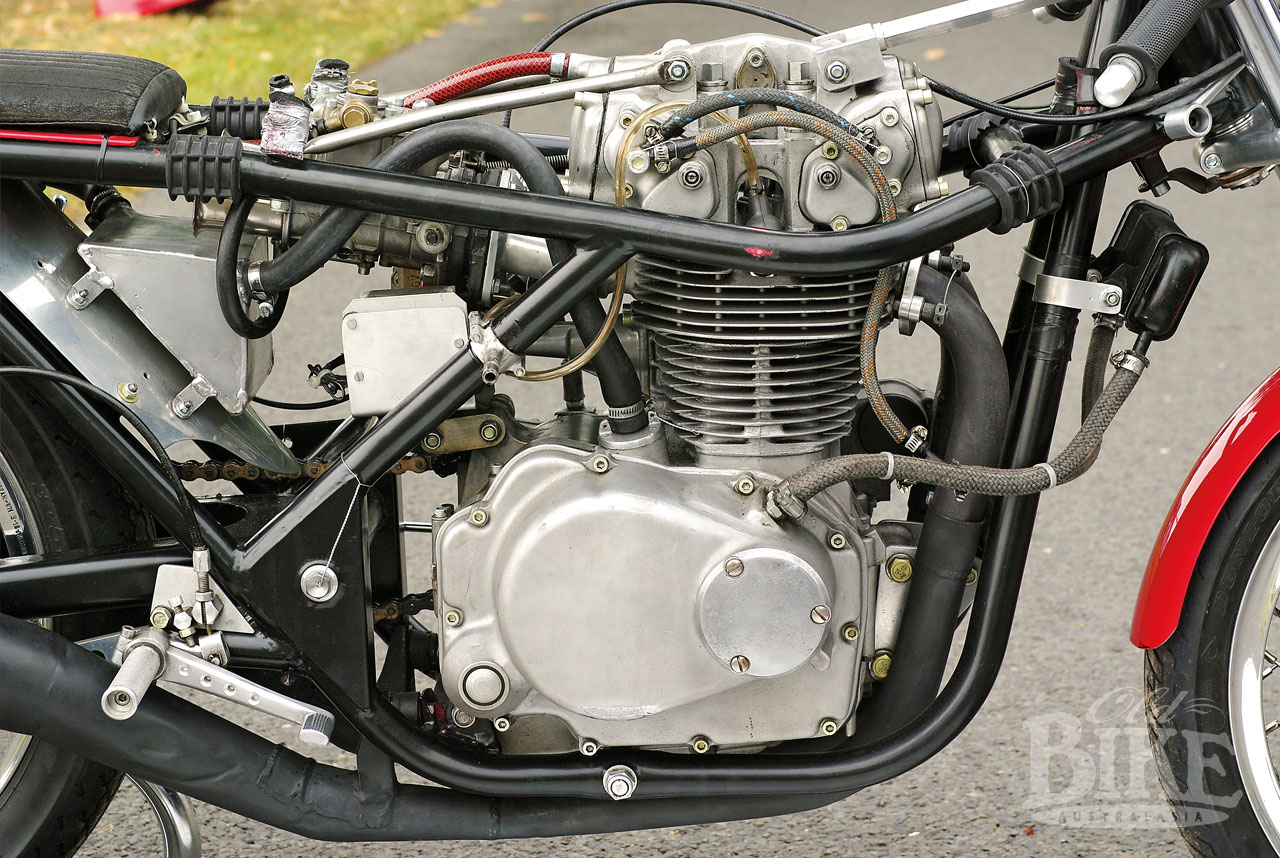

Meantime the two Aussies set about tuning the CB450 Honda engine, which remarkably enough came in two versions – with a two-up 360º crankshaft for the Japanese home market, and a one-up/one-down 180º type for the export version which formed the basis of the first Drixton Honda. However, the Aussies sourced a special lightweight 180º crank and conrods from the copious parts suppliers in northern Italy, then fitted Aermacchi valves (41mm inlets and 35mm exhausts) and coil valve springs, to replace the standard torsion-bar valve train. They then bored the engine 4mm to 74 x 57.8 mm for 497cc using Aermacchi race pistons, ported the cylinder head, and fitted higher-lift American Webco race camshafts. The carburettor they used was a 45mm twin-choke DCOE Weber from an Alfa Romeo car, then a common piece of tuning kit for Italian and British sports cars, matched to exhaust pipes made for them by Rob North in England. The stock Honda coil ignition was retained with full advance fixed at 45 degrees – Kröber self-generating electronic CDI wouldn’t be available for another couple of years – with the consequent handicaps of weight (a heavy 12v battery was required) and reliability at the sustained higher revs this race motor targeted. But in this guise the first Drixton Honda’s engine produced 65 bhp at 10,200 rpm at the rear wheel – a substantial step up from the 52bhp of a good Manx Norton or Seeley Matchless, without too much of a weight penalty. In later life fitted with Kröber ignition, the Drixton Honda weighed in at a very competitive 129kg dry, equally split 50.5/49.5% front to rear.

This favourable distribution was achieved by Drixl positioning the Honda engine quite far forward in his tubular steel duplex cradle frame, whose short 1340mm wheelbase meant the ensuing bike was fairly quick-steering. Extra stiffness was obtained via a robust-looking thick aluminium rod stamped by Marly with ‘Drixton 1968’ which connected the rear of the frame’s steering head with the forward of the pair of engine mounts cast into the cylinder head, plus a pair of slender tubes running backwards from the rear such mount to locating points screwed into the frame rails which acted as non-structural engine steadies. The lateral frame tubes wrapped around the cylinder head to act as engine protection in the event of a crash. A 35mm Ceriani fork set at a 27º rake with a tubular steel swingarm with eccentric chain adjustment and twin Ceriani shocks were complimented by Fontana brakes – a massive 250mm four leading-shoe front drum, and 210mm twin leading-shoe rear – all off-the-shelf items made in and around Milan.

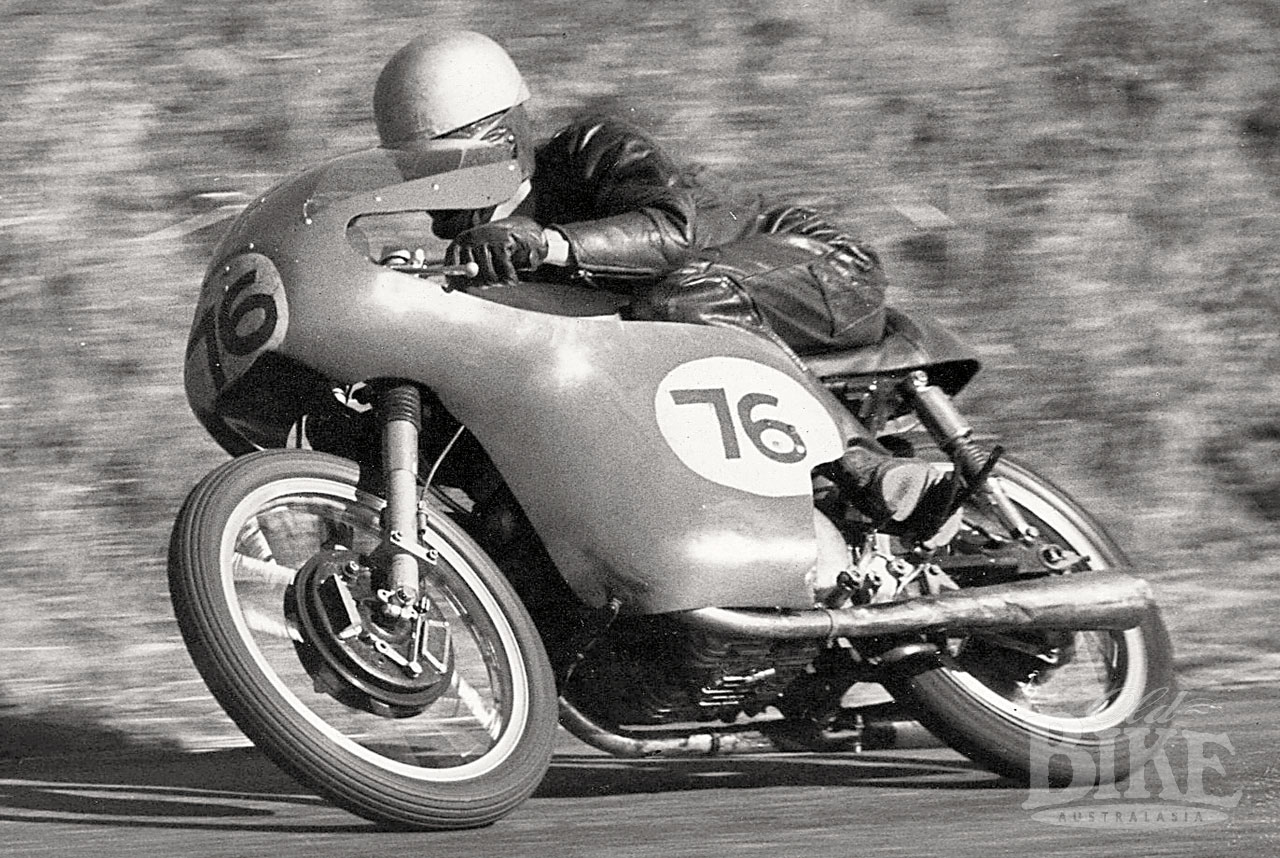

After some springtime shakedown races in the early season Temporada di Primavera street races on the Adriatic Coast, Terry Dennehy’s GP debut with the Drixton Honda came in the 1969 Dutch TT at Assen on June 28, ending inauspiciously with retirement owing to ignition problems. But in his next outing on the bike in the East German GP at the Sachsenring on July 13, the Aussie suffered the heartbreak of running out of petrol on the last lap while holding a secure second place behind the victorious Agostini’s works MV Agusta, although Terry eventually pushed the Honda home to claim fifth place in the end. Next time out on August 3 he actually led the Finnish GP at Imatra, ahead of Ago, only to retire with ignition problems – a disappointment felt by the whole paddock, which had never seen a privateer challenge the red and silver MV fire engines, and especially not with a home brewed motorcycle like the Drixton Honda. Again, at the Italian GP held on September 7 that year at Imola rather than Monza, Dennehy ran a strong second behind eventual race-winner Alberto Pagani’s works Linto, before an engine misfire slowed him, though he finally coaxed the Honda over the line to finish fourth. In the season-ending Yugoslav GP at Opatija a week later, he retired once again with perennial ignition woes – but still, he’d scored enough points to finish 12th in the 500cc World championship – one place ahead of fellow-Aussie and co-resident of Milan, Jack Findlay.

The Drixton Honda was obviously capable of being a really competitive privateer’s tool, even with the arrival on the scene in 1970 of the Kawasaki H1R two-strokes which were blindingly fast, but required the engineering talents and on-bike understanding of a Ginger Molloy to be kept running – aided by Ralph Hannan, who joined forces with the Kiwi two-stroke ace when Dennehy eventually ran out of money. But with his race budget swollen by the beginning of what would later become a prime time business career shifting luxury Italian sports cars, Dennehy planned to do the entire 1970 GP season with the Drixton Honda, except for the TT and Ulster GP on the grounds that he couldn’t expect to do well there on his debut, and the weather as he saw it was likely to be damp and cold.

After the customary shakedown races in the Temporada di Primavera, Dennehy took the final championship point by finishing tenth in the season- opening German GP on the Nurburgring on May 3 – good going for his debut race on such a difficult track. But the next two races saw him DNF in both the French and Yugoslav GP (the latter after once again running a firm second behind Ago, only to retire with oiled plugs), and 13th in the Dutch TT at Assen. Better was to come at Spa-Francorchamps one week later, when he finished sixth in the Belgian GP, albeit one place behind British rider Lewis Young on another Drixton-framed Honda. More retirements followed for Dennehy and his Drixton at Imatra, Monza and the season-ending Spanish GP at Montjuic Park, to conclude a disappointing season. However, Terry had by now fallen into the Italian way of life, and was by now fluent in French and Italian. To supplement his income, he’d begun buying and selling luxury cars, building a strong client base in Europe and the USA, and developing an especially close relationship with Ferrari, for whom he’d become a trusted source of customers. This meant racing now came second to shifting four-wheeled metal for Terry, and so he decided to dispose of the Honda.

At the 1971 Dutch TT at Assen Dennehy started talking a deal with Dutch privateer Ben Heman to part with the Drixton, and the deal was concluded the next weekend at the Belgian GP at Spa. It entailed a straight swap for Heman’s brand new Yamaha TR350, allowing the Dutchman to move into the 500cc class, and Dennehy to join the two-stroke revolution, albeit in the smaller category. It didn’t bring him much luck, though, for in 1972 racing in Sweden he crashed and broke his femur, effectively ending his racing career. He moved to the south of France with his partner Danielle and son Neil, trading in expensive motor vehicles and often popping up at bike race meetings until on 31st December, 2001, he died in Belgium just 24 hours after contracting meningococcal disease, an ultra-aggressive form of meningitis. He was just 55 years old.

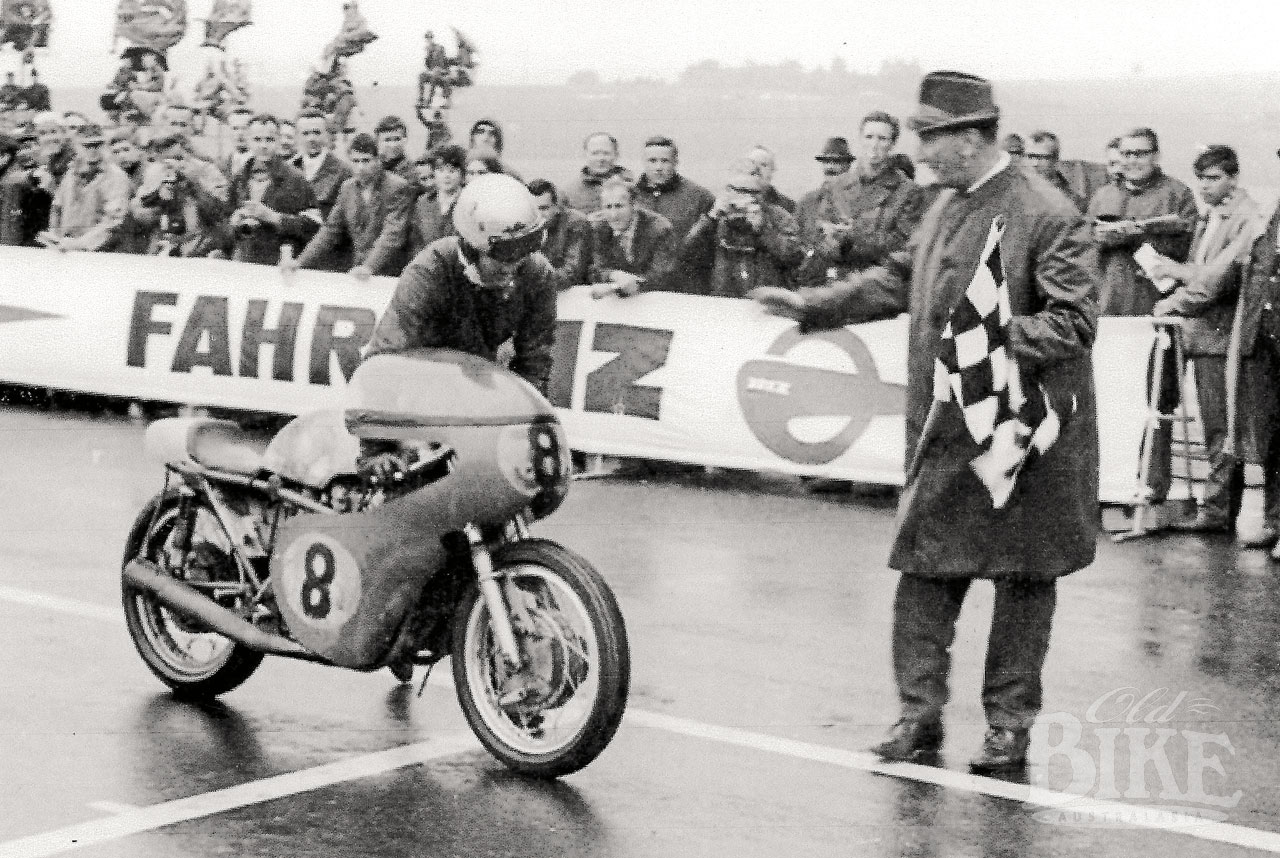

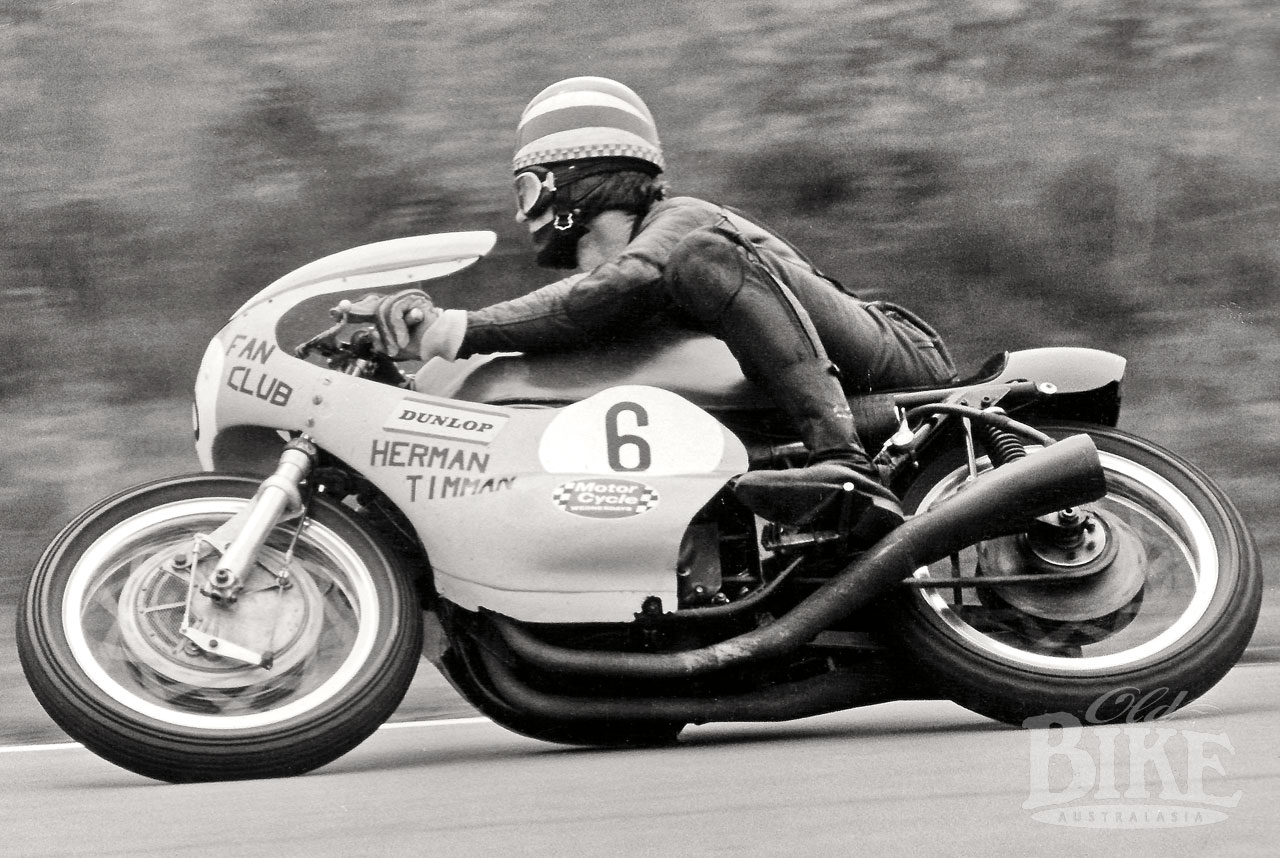

Ben Heman kept the Drixton Honda for a year, before approaching his friend and fellow racer Herman Timman to see if he’d be interested in acquiring it. Timman takes up the story: “I’d been racing since 1967. Ben Heman approached me to see if I was interested in buying his 500 Drixton Honda. Well, I didn’t need to think twice about that, but money for me was the problem. Fortunately, Ben agreed on a part exchange, with some cash up front and some spare parts to make up the difference, including a 350 Manx cylinder head, a complete 250 Ducati street bike, etc. As soon as I did my first laps at Assen on the Drixton Honda, I knew this could be the bike to win the Dutch 500 Championship on. It was in really great condition, with a lot of power compared to what I was used to, but so controllable – it had a really wide usable power band, and the handling felt perfect – and remember I was used to racing a Manx Norton, so I had high standards! And also there was the fantastic sound – it had a great exhaust note in those pre-silencer days. But because I had already missed the first five races in the 11-round Dutch Championship, I had to give it everything in the remaining six races to win the title. Well, I did manage to win the next five races in succession, leaving it only necessary to finish in the top four of the final round at Assen to win the championship. I followed my closest rival Frank Coopman on his fast three-cylinder Kawasaki all through that final race to finish second, and so I became Dutch Champion that year. I was very happy!”

“Unfortunately, I had to sell the Drixton Honda in 1974,” recalls Herman, “then years went by and it belonged to various people in the Netherlands and Germany before in 2004 a Dutch collector named Mr. Schermer Voest bought it, and showed me the bike. Unfortunately, he later passed away, but his relatives offered me the chance to buy my former racer back after all these years. Of course, I couldn’t resist this once in a lifetime chance, so I bought it. There had been quite a few modifications to the bike down the years, but nothing that could stop me bringing it back to original condition – it had Mikuni carbs, for example, but fortunately the twin-choke Weber and its manifold were still in the box of spare parts I got with it. With the help of our local Aermacchi wizard Jan Kampen we managed to get the bike running again like new, so now I’m very proud to be able to ride the genuine first ever Drixton Honda 500 in Classic parades today.”

My chance to ride the genuine original ex-Terry Dennehy 500cc Drixton Honda came on the 2.5km public roads circuit laid out on the edge of Basse, a village just 100km northeast of Amsterdam, which for the past 22 years has staged the annual Basse TT Historic racing event held annually in September.

Being asked to open the course for the day’s events via a three-lap dash in solitary splendour aboard the Drixton Honda meant I had to combine course-learning with understanding how to ride the bike. I needn’t have worried, though, because the Drixton Honda proved uncannily similar to ride to one of its closest rivals in the 1969/70 GP seasons, the ex-Billie Nelson 500 Paton I owned and raced more than a quarter of a century ago.

Like the Paton, the Honda is a 180º parallel-twin (so, one-up/one-down) with a patch of megaphonitis from its twin exhausts between 5,000-5,500 rpm that you have to work the clutch to try and avoid. But it pulls pretty strongly from 3,000 rpm upwards, so drove well down low out of the trio of hairpins on the Basse circuit. However, Herman Timman had the bike still geared for his previous outing on it at the annual Bikers Classic meeting on the big Spa-Francorchamps GP circuit, so being overgeared meant using bottom gear three times per lap at the hairpins before running it up to the 9,000 rpm limit in the gears that Herman uses on the bike today. The Drixton’s Honda engine is more torquey than the Paton, with a stronger midrange pull in its 7,000-9,000 rpm happy zone. This greater flexibility would have made the Honda a good tool for tighter tracks. Ralph Hannan must have sourced a five-speed race cluster from one of specialist companies in northern Italy who supplied such hardware and it is pretty slick, with the top three ratios pretty close together in what is a typical Italian 1960s gearbox aimed at keeping up the revs on a fast track like Monza or Imola.

I ended up getting a good grounding in the required push start technique, which is just as tricky on the Drixton Honda as on the hard-to-start Paton. Even with the long Spa gearing fitted it’s better to use second gear, then catch the engine as the 180º crank fires on one cylinder and the other one joins in, leap aboard, hit bottom gear, and then go for it. Push-starting the bike in a crowded grid must have been pretty tricky, and the Kawasaki/Suzuki two-stroke opposition would have been shifting into third gear by the time you’d have got the Honda fired up, used the clutch to head for the promised land above 5,500 rpm where the engine pulls hardest, and were then ready for action.

When it catches fire the Honda engine sounds gloriously angry, via the roar emitted by its pair of open meggas. It has a superb exhaust note that you’re aware of all the time you’re aboard it – deep, meaty, powerful and fruity. The throttle action is very light, thanks to the car-type butterflies in the twin-choke Weber carb, which betrays its automotive origins, by the way it doesn’t much like part-throttle openings. There’s a strong pickup out of a turn if you crack it wide open, but feed the throttle in gradually transiting a tighter bend and it hunts slightly, then splutters before clearing itself and coming on strong as you ease the throttles open.

But the biggest asset of the Drixton Honda is the excellent handling delivered by Marly Drixl’s duplex chassis which delivers literally the best of both worlds – it’s planted in the fast turns, and nimble in tighter tracks. Its Ceriani suspension was the benchmark kit of the late 1960s, and the way the bike goes round corners as if on rails is extremely confidence-inspiring. It feels safe, steady and sure, with neutral steering and predictable handling, plus the superb confidence-inspiring braking delivered by its pair of Fontana drums. These were the outstanding brakes of the pre-disc brake era, and actually worked a lot better than the early Japanese stainless steel discs.

The Drixton frame’s riding position is very ‘60s, with high footrests and a fairly long stretch over the fuel tank to the steeply dropped clip-ons. It feels pretty short and relatively porky, though, which with a 1340mm wheelbase it indeed is. By the time Herman acquired it the Honda had been fitted with the Kröber electronic ignition it now carries, matched by the same company’s tacho with a red reminder strip at 9,000 rpm, and a yellow one at 10,500 revs standing for $$$$!

Marly Drixl may have been a flamboyant character, but judging by my ride on Herman Timman’s ex-Terry Dennehy Drixton-Honda 500, he also knew a lot about building motorcycle frames. What a pity he didn’t stick at it – although many others around the world have done so for him. They chose a good bike to copy.

Drixton Honda 500 – The other originals

Surprisingly, in view of the more than adequate performance that proved to be extractable from the production Honda CB450 engine, coupled with its reasonable cost, it seems that only four real Drixton-framed 500cc Hondas were ever actually built by Marly Drixl himself. Besides Terry Dennehy’s bike which provided the template for the other three, a second machine was also purchased in 1969 by Swiss GP privateer Jean Campiche, who raced it in the 1970 and 1971 GP seasons, but it’s unclear what happened to the bike after that. British Continental Circus stalwart Godfrey Nash also acquired a Drixton frame from Marly in 1969, the year that he became the last man to win a World championship GP race on a Manx Norton. Nash reasoned that the Drixton Honda was a suitable replacement for the Norton and purchased a chassis from Drixl, then built the bike up himself but then came the news that his sponsor John Tickle had purchased the rights to the Manx Norton design and wanted Nash to race for him in the 1970 season. This made the Drixton Honda surplus to requirements, so Nash sold it to fellow GP privateer Lewis Young, who rode it in the 1970 GP season with a best result of fifth in the Belgian GP. After that, the bike was sold to Brian Lee, one of Syd Lawton’s protégés.

A fourth bike was also constructed by Drixl for an Aussie mate of Dennehy’s, Ray Brennigan – but Drixton frame production came to an end in 1969 after Marly suddenly disappeared from Baroni’s workshop under something of a cloud, later resurfacing just across the Swiss border having opted out of the motorcycle frame business altogether in favour of an electrical supply company. The Brennigan Honda later wound up in the UK in the hands of Dick Linton, himself a Drixton Aermacchi racer who had taken over the Aermacchi racing parts business from Syd Lawton on his retirement. In 1985 the Honda was sold to an American friend of mine, Pennsylvanian Pete Johnson. Aided by the preparation skills of noted tuner Eraldo Ferracci, Pete swiftly became unbeatable on the Drixton Honda 500 in the USA, defeating Team Obsolete’s Isle of Man TT-winner Dave Roper to win the 1987 AHRMA 500 Premier title. Pete then sanctioned the construction of two identical replicas of his Drixton chassis, these being the first of what would be hundreds of copies of Drixl’s design, to a greater or lesser degree of accuracy.

Former racer Asa Moyce, a Londoner who’d moved to Ulster, built more than 100 frames. The Moyce machines have ended up around the world, and have themselves in turn been copiously copied by others – most of them differing in several respects from the original Drixton frame, including the steering geometry. Many have also concocted a 350cc version of the Drixton frame to accommodate the smaller capacity CB350 variant of the Honda parallel-twin engine, although strictly speaking these should never have been accepted as eligible for Classic racing, at least under CRMC rules, since no such bike was ever constructed in the Classic era. Marly Drixl only ever built 500cc Drixton Hondas, and it seems that he only made four of those before returning to Switzerland in 1969, and opting out of the frame-building business.

Drixton Honda 500 – Specifications

Engine: Air-cooled dohc parallel-twin four-stroke with 180-degree crankshaft throw and central chain camshaft drive

Dimensions: 74 x 57.8 mm

Capacity: 497 cc

Output: 65 bhp at 10,200 rpm (at rear wheel)

Compression ratio: 12.2:1

Carburation: 1 x twin-45 mm choke Weber DCOE

Ignition: Kröber self-generating electronic CDI

Gearbox: 5-speed with gear primary drive

Clutch: Multiplate oil-bath with bronze Surflex plates

Chassis: Tubular steel duplex cradle frame

Suspension: Front: 35 mm Ceriani telescopic forks

Rear: Tubular steel swingarm with 2 x Ceriani shocks

Head angle: 27 degrees

Wheelbase: 1340 mm

Weight: 129 kg dry

Weight distribution: 50.5/49.5%

Brakes: Front: 250mm Fontana four leading-shoe drum

Rear: 210mm Fontana twin leading-shoe drum

Wheels/tyres: Borrani wire-wheeled rims

Front: 2.75/3.75-18 Dunlop KR325 on WM2/1.85 in.

Rear: 3.50 x 18 Dunlop KR174 on WM4/2.50 in.

Top speed: 155 mph/250 kph on Spa-Francorchamps gearing

Year of construction: 1968

Owner: Herman Timman, Paasloo, Netherlands