For six years, Suzuki defied conventional wisdom when everyone else was going four-stroke. What the release of the Honda CB750 in 1969 created was not so much of a rush as a stampede, for this machine had finally lain to rest the myth that the Japanese were incapable of building big bikes. And while the basic in-line four-cylinder four stroke eventually became the standard design, for a few years there was a plethora of highly original models pouring out of Japan. Yamaha went the parallel twin route, but Suzuki stuck to its two-stroke guns – as did Kawasaki, at least initially.

Having taken some years to refine the air-cooled T500 twin from an awkward looking, overweight misfit to a quite refined machine (and a handy racer in the form of the TR500), Suzuki was understandably reluctant to dump their two-stroke platform just yet. Besides, adding just one more of the T500’s 70 mm x 64 mm cylinders would produce a 738cc 750-class Superbike without creating an entirely new design, so that’s what happened. Even the Candy Lavender (purple) and white colour scheme came from the T500. In fact, the GT750, as well as the T250 and the T500 were all the work of the same designer, Etsuo Yokouchi, who went on to pen one of the most significant racing machines of all time – the RG500 square four. Mind you, the triple had to endure a rather lengthy gestation period. First shown to the world at the Tokyo Show in October 1970, more than a year (and another Tokyo Show) slipped by with no sign of the production model.

Inherently, a two stroke should have been considerably lighter than a four-stroke as well, but in practice, this didn’t work out. At 214 kg dry, the GT750 Suzuki was marginally heavier than the CB750. It was wide too, thanks to the enormous but necessary radiator. However the gleaming, all-alloy water-cooled engine was undoubtedly a magnificent creation, producing 67 bhp at 6,500 rpm, hitched to a five-speed gearbox. Water-cooled large capacity two-strokes weren’t exactly new, the British Scott having stuck to this successful formula for many years. Indeed, Scott had shown a three-cylinder, 747 water-cooled triple as early as the 1934 Olympia (London) Show, but it never went into production. In more modern times, Kawasaki had pioneered the triple cylinder two-stroke, firstly with the H1 (or Mach III, which is what it felt like under acceleration) and later with the 750cc H2, both air-cooled.

Inside the horizontally-split GT750 crankcase were four large main bearings supporting the crankshaft, which had throws spaced 120-degrees apart. On the left end of the crankshaft sat three sets of points, with an inboard gear driving the tachometer and the vane-type water pump, located in the bottom of the crankcase. Primary drive was taken from between the second and third cylinders, with the outer (right) flywheel assembly grafted onto the primary gear. The cylinder block was cast in one piece, with non-removable cast-iron liners. Similarly, the head was a one-piece unit. In search of smoothness, the engine was rubber-mounted to the frame.

Curiously, in an age when disc brakes were all the rage, the first GT750 stuck to a front drum; admittedly a real beauty. The 200mm double-side, twin-leading shoe front stopper looked just like the equipment seen on GP racers, and became highly sought-after as a competition component in many a special, despite its significant weight. A 180 mm rear drum brake, sourced from the T500, was fitted. The centre cylinder’s exhaust system split into two, these two employing the same volume as the larger (top) mufflers servicing the outer cylinders. It also had the effect of giving the GT750 the appearance of a four-cylinder machine, at least from the rear. The radiator cap was hidden from view under a flap at the front of the fuel tank.

Pre-production models of the GT750 were displayed around the world in November 1971, with five machines being flown to Australia late that month. The first production model, the GT750J (J signifying the 1972 production year) arrived in decent numbers around February, where it was immediately compared to the other two-stroke triple on the market, the Kawasaki H2. In reality, while they shared that same basic specification, the two machines were poles apart; the H2 a raw, racy, rattling air-cooled street scorcher that out accelerated and out braked the Suzuki, cost and certainly weighed less, but it is unlikely the H2 stole any potential customers from the GT750. Suzuki’s triple was pitched as a comfortable, smooth, refined tourer, a bit on the porky side perhaps, but still capable of turning a standing-quarter in 13-odd seconds. To be fair, most of the Suzuki’s extra weight came from its main point of difference over the H2 – water cooling. This added a radiator, water pump, thermostat, hoses, larger castings to accommodate the water jackets and coolant, so the extra 30 kilograms was understandable. And with the liquid gear came a string of sobriquets – the GT750 became known as the Kettle in the UK, the Water Buffalo in the USA and the Water Bottle in these parts.

Handling was considered adequate, with serious scratching limited by lack of ground clearance. The centre stand would make contact with the road without too much provocation.

In its second production year, the GT750K underwent one significant change. Out went the big double-sided front drum, to be replaced by a pair of 295mm discs – in swept area, the biggest stoppers on the market. Inside the engine, a revised system of preventing oil build up in the crankcase was employed. Extra chrome plating, notably on the sides of the radiator, replaced some painted surfaces.

The short-lived L-model appeared in August 1974, with increased baffling to the intake system to reduce audible drone, a mod which badly affected acceleration. There were slimmer side panels with chrome plated front panels and a gear indicator within instrument panel, while the engine now produced 70 bhp due to revised porting and larger 40 mm carburettors, now of the constant-velocity type mounted in a rack rather than individually with a single push/pull cable arrangement. Exhausts were altered in an effort to gain more ground clearance and the fan now listed as an optional fitment at the dealer.

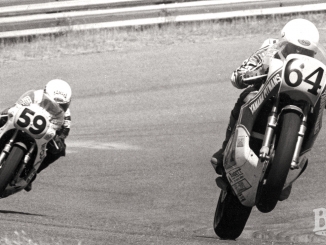

The real revamp came with the M model, which was first released in Japan in October 1974. The GT750M gained even more ground clearance from an entirely new exhausts system with the balance pipes removed from the headers. The cylinder head was shaved by 0.2 mm and the head gasket reduced in thickness from 1.5 mm to 0.8 mm. Compression ration went from 6.7:1 to 6.9:1. These were all factors in the decision to enter a GT750 in the 1975 Castrol Six Hour Production Race at Amaroo Park, where it was ridden by Alan Hales and Bill Horsman. Despite an early spill by Horsman, the GT finished in 11th place.

Less piston clearance gave slightly quieter running, with aluminium rather than phenolic plastic clutch plates. A major change in the overall feel of the machine resulted from higher final drive gearing – from 3.13:1 to 2.69.1 – as a result of a higher internal fifth gear. However less torque and the higher gearing made it sluggish on takeoff, coupled with greater overall weight, which was up to 556 lb (252 kg) wet.

Apart from a lockable cover on the fuel tank (as on the new GS750), there were few other changes for the 1976 model year. With the success of the new four-cylinder four-stroke, the GT750’s fate was sealed, and the GT750B, released for the 1977 model year, was the last of the line. Visually, this was probably the biggest departure from the original styling, and mirrored much of the look of the GS750, using the same indicators, tail light assembly and similar brown-faced instruments. The front mudguard lost its traditional front and bottom stays, and side panels became black along with the headlight shell. In fact, there had been a serious cost-cutting exercise by Suzuki on both the A and B models. Many chrome-plated components became zinc-finished.

The Suzuki GT750 – Production statistics (worldwide).

Model/Year from frame no from engine no total run

GT750J/1972 10001 10001 21252

GT750K/1973 31253 31357 8994

GT750L/1974 40247 43047 12576

GT750M/1975 52823 57537 8906

GT750A/1976 61729 67558 14010

GT750B/1977 75739 82605 10,000 approx

Suzuki ran two parallel assembly lines for the GT750. Although frame and engine numbers began at 10001, they soon got out of sequence due to quality control, where crankcases were scrapped and the next number substituted.

Mr Water Bottle

In Australia, and indeed internationally, Steve Thompson is the walking almanac on the Suzuki GT750. He should know what he’s talking about – he owns 28 of them. Steve knows every minute model difference and special factory modification, and he is happy to share his knowledge with GT owners worldwide. Currently, he has fully restored J, K and A models, with L, M and B models under way. He also aims to have one of each colour of the original drum-braked J model. To complement the Candy Lavender model featured here, he also has partly-completed Candy Jackal Blue and the Europe-only Candy Yellow Ochre J-models. One of these will be fitted with another rare item in his possession – a two-piece cylinder head. “Suzuki was initially a bit worried about overheating, so they made up cylinder heads that contained a larger-volume water jacket, with a removable top section. These were only used on a small number of Japanese home-market models over a two-year period, so they are very rare. Naturally, they require special lengthened sleeve nuts because of the extra thickness of the head, and Suzuki in Japan has recently re-made a batch of these. In the end, it (the water-cooled head) was not required – even the fan was removed after the first two models – and never appeared on export models.” He points to the optional Bakelite steering damper knob on his GT750A. “That’s rare. I bought a whole bike just to get that steering damper!”

There are quite a few tricks and pitfalls for the would-be GT750 restorer, and Steve knows them all. For instance, minor changes in the mounting for the tail light bracket for the J model means that not they are not completely interchangeable between other models. So when you buy a basket case and the tail light won’t line up with the holes in the mudguard, it means you have parts from two (or more) different models. Mid-way through the A model run in 1976, Suzuki modified the profile on second and third drive and driven gears “to increase durability.” These had one tooth less and are now the only items available from Suzuki, meaning they must be replaced as a set. Quite a few owners have discovered when ordering a single gear, the new (modified) one is supplied and won’t fit the earlier models. Carburettors also varied significantly between models and there were numerous changes to instrument faces and surrounds, as well as items such as air-boxes, side covers and trim.

By the time of the A and B models (1976-77), Suzuki was in serious trouble selling the two-stroke in the face of the opposition from Kawasaki’s Z1 900, and indeed, its own new GS750. Consequently, few of the GT750Bs were sold in Australia. “I was working at Ryan’s Motorcycles (Suzuki dealers) in Parramatta,” says Steve, “and we still had A models on the floor when the B came out, so we never sold any of the last model. John Steain (owner of the GT750L featured here) was with (NSW Suzuki distributor) Hazell & Moore and he can’t recall having any B models at all. I think the only GT750Bs sold here were in Victoria and South Australia, so they’re pretty hard to find in Australia.”

Steve is quite clear on his future plans. “My goal is to have one of every year model in factory original condition, and when I have achieved that, I will divest myself of the 20-odd others I have, either as basket cases or semi-finished but complete bikes.” There’s no doubt the GT750 is a truly iconic motorcycle, with a large and devoted world-wide following. It is, to use a hackneyed phrase, a “practical classic” – a motorcycle that can undertake significant touring miles in relative comfort, and with excellent reliability. Parts are reasonably plentiful, from Suzuki itself and a network of specialist suppliers around the world. And when the surplus contents of Steve’s shed come onto the market in the not-too-distant future, there will be an even greater number of happy Water Bottle owners.

Water and wine?

In 1976, Suzuki was in the unique position of having two entirely different 750 models in its line up. And you can’t get more different than a three-cylinder water-cooled two stroke and a DOHC air-cooled four-cylinder 4-stroke. They even had a Rotary if that was your bag.

We’ve already dealt with the story of the development process behind the GS during the course of our two-year restoration, so the big question is, how do these chalk and cheese 750s stack up? The best man to answer that question would be noted restorer Wayne Waddington, who owns one of each – a GT750M and a GS750B, as well as the RE5 Rotary featured in OBA 3. Over to you Wayne…

“In my humble opinion, there is no comparison. The only thing I found (in the GT’s favour) riding them back to back was that the GT seat was more comfortable. The GS is significantly superior in the front suspension and slightly superior in the rear. Steering is much better and ground clearance significantly better. The engine produces better torque and is more powerful, with better fuel consumption. The front single disc on the GS appears to be at least a match for the twin discs on the GT – don’t ask me why, it still has only a single piston calliper – and the rear brake can only be criticised for being too powerful. A little while ago I did some top gear roll-ons with the GT/RE/GS. They were the average of at least 3 timed attempts and all done on the same stretches of road. And more importantly, the GT750M sported the optional lower gearing using a 15 tooth front sprocket compared to the usual 16 tooth. The stock 16 tooth makes the bike pathetic, the B model was also pathetic using the stock gearing of 15/40 as opposed to 16/43 on the M. The end effect is almost identical- way overgeared. I owned one from new in 1977. Even road tests of the day commented on it and some changed the gearing. I dropped my B model to 14:40 and it transformed the bike’s performance. This (the gearing change) was apparently done to pass a U.S. 60 mph drive-by noise test. As far as I know, the M and B GT engines were identical performance wise. I actually think that the GS is capable of slightly better times, although my one has a bit of a flat spot in the midrange which I haven’t tuned out yet. But how about that RE – and it is the only one with an original engine somewhat down on compression. The other two are nicely run in after full rebuilds! I’ve also done side-by-side top gear roll-ons for the RE versus GT with a mate on one of the bikes. The old RE leaves it for dead but I think that the tables would turn with a roll on above 110 or 120 kph. I believe that that wouldn’t be the case with GS vs GT though.”

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook