The SR60 was one man’s dream of building an all Australian machine to beat the ESOs, Jawas and JAPs that dominated the sport.

Story: Dave Basham with input from Steve Magro, Alan Jones • Photos: Jim Scaysbrook, Ben Ludolphy

SR60-AUSTRALIA – the badge is a rich red oval and the lettering stands out proudly, matching the thick golden enamel of the border. It came about in 1972 as the brainchild of Adelaide man Fred Jolly – engineer, dealer, sponsor, garage owner and designer/builder of the first wholly Australian speedway machine. SR stands for Southern Racing and 60 indicates the horsepower output of the engine. Fred believed that his association with speedway that spanned some 40 years, plus five years of design and development that had cost him $35,000 – had resulted in the best speedway bike in the world.

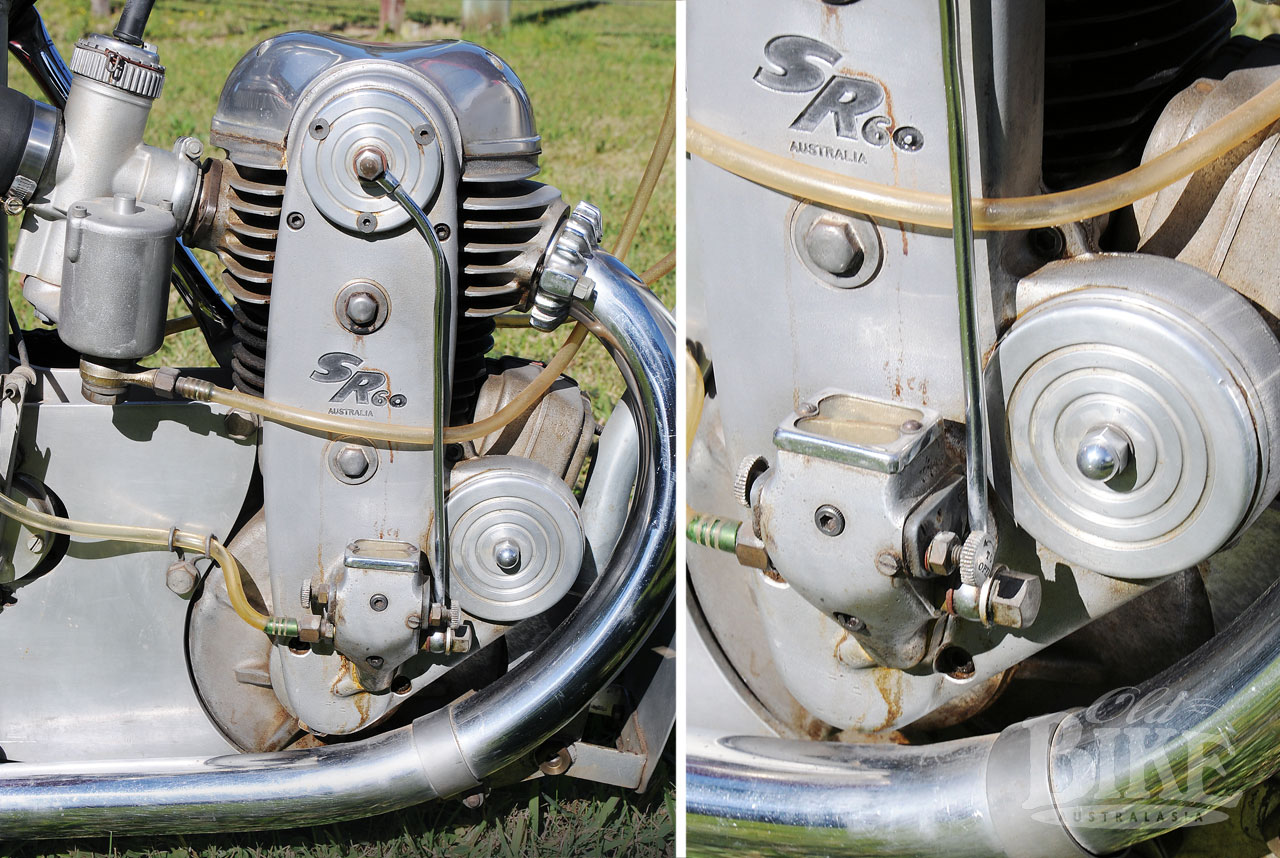

From the early ‘sixties, the Czechoslovakian ESO had started to prove a better prospect than the long standing JAP powered machines, and it was around the ESO that the SR60 was conceived, but updated and incorporating several modifications to engine and frame to increase power and avoid breakages. The major change in the SR60 design was the use of a single-overhead camshaft; both the ESO and JAPs being pushrod engines. The OHC layout gave an immediate increase in useable engine revolutions because the valves are better controlled – and broadly speaking, more revs means more power. Apart from the system of valve operation the SR60 head is similar to that of the ESO. Valves are English made copies – both in shape and metal (austenitic steel) – of the ESO parts and the ports were exactly the same shape as is the combustion chamber. The SR60 also shares bore and stroke measurements with the ESO – 88mm bore and 82mm stroke – but the connecting rod of the SR60 is shorter. Fred claimed that this was an aid to low-speed acceleration. It also made the engine one inch lower (19″ or 48.2 cm) than the ESO.

The whole engine was cast in a new alloy – A356 – developed by Comalco with a $3 million Commonwealth Government grant. Though of the same weight as other aircraft quality alloys, A356 is considerably stronger. The barrel was nickel iron. A 35 mm Dell ‘Orto carburettor was fitted along with a special float-bowl designed and developed by Jolly.

After two years of experimentation, Fred settled on the Lucas rotating-magnet SR1 magneto. The same type was used on such racers as the Manx Norton, but was out of production. Lucas agreed to make them for the SR60. Oiling was taken care of by a British Pilgrim Pump, the same as was used on JAP machines and similar to that used on the ESO. Net result of the engine variations was that the SR60 developed 60 bhp at 9,000 rpm compared with the 55 bhp at 8,000 rpm of the ESO unit. It was a similar power differential which allowed the ESO to oust the JAP from the speedway tracks of the world.

But the SR60 was not simply a more powerful version of existing speedway types, it was developed to cut down maintenance and prevent the troubles which afflict engines subjected to the harsh life of speedway. The cam drive (by gears in a tunnel up the side of the motor) can be removed complete with the magneto and without disturbing the timing, simply by removing 4 Allen-bolts. Similarly, the magneto may be swapped in only a couple of minutes.

The frame is almost exactly similar to that of the ESO, produced by the Uhser’s Custom Exhausts in Adelaide. The geometry of steering head and fork angles is exactly the same, but a strong cold-drawn steel gusset is fitted at the head-stem and two more gussets support the weld between the main frame and the lower tubes running to the back wheel.

The workmanship on the prototype was impeccable. Every item – even down to the clips to hold the fuel line in place – was expertly made and finished. The engine castings, by Ellery’s Foundry of Adelaide were magnificent, the heads being almost blemish-free and an unmachined head-blank needed only internal polishing. The fibreglass work on mudguards and fuel tank was of a similar high standard – with metal flake colouring cast in so it could not wear off.

Fred Jolly – visionary

The late 1940’s found Fred as a motorcycle dealer in Adelaide. He was then selling JAP-engined roadsters called AJWs – made in England by by A.J. Wheaton. When the AJW factory asked whether Fred would be interested in having a speedway iron to promote the road bikes he jumped at the chance. The bike duly arrived and Fred asked a then-unknown Adelaide rider called Jack Young to ride it. Young had not yet ridden on a genuine speedway bike. He broke the lap record at Rowley park first time out and was later picked to ride for Australia when he beat the legendary Jack Parker. Young became the first rider that Fred sponsored but not the only World Champion – he later supplied machines for Ivan Mauger in Australia before he came to Britain.

Then one day in the early 1960s, a friend of Fred’s brought back some catalogues from the World’s Trade Fair in Prague, and he realised that the speedway machine listed in it offered more potential than the JAPs. After writing to the Czech ESO company, he received an initial bike to test, and later received a further 20 machines which sold immediately. But equally immediately, the engines exploded when first raced. The factory had fitted high-lift moto-cross cams and with the high-domed speedway pistons, the engines smashed themselves to pieces.

By the time Fred had the 20 machines rebuilt and returned to the owners a year had gone by and New Zealander Barry Briggs was riding in Australia – fresh from winning the World Title on what was called the fastest JAP in the world. Jack Young blew him off on an ESO and Briggs was so impressed he asked Fred Jolly whether he could test the ESO. He did and then took Fred’s advice by going to Prague and securing the English agency for the Czech flyers. Briggs was responsible for the machines taking over in England, but it was Fred Jolly who brought the first one from behind the Iron Curtain. He continued importing them until a change in factory management after the Russian take-over of Czechoslovakia in 1967. “They kicked out all the Czechs I knew in the foreign export division and I got the raw end of the stick on the business side of it,” he said. “They wanted to supply all their Jawa/CZ roadster dealers in each State with dirt-track machines. So I said I was finished.” He vowed to make his own machines to beat the Czech racers. He decided he would make a complete copy of the Jawa (it was still then known as the ESO) and call it an SO – with the S superimposed over the O. “The whole machine was going to be made in Japan by the Fuji Aircraft Corporation. But the trouble was they could not begin to look at the project for 18 months. I couldn’t sit around for 18 months so I started on the project myself.”

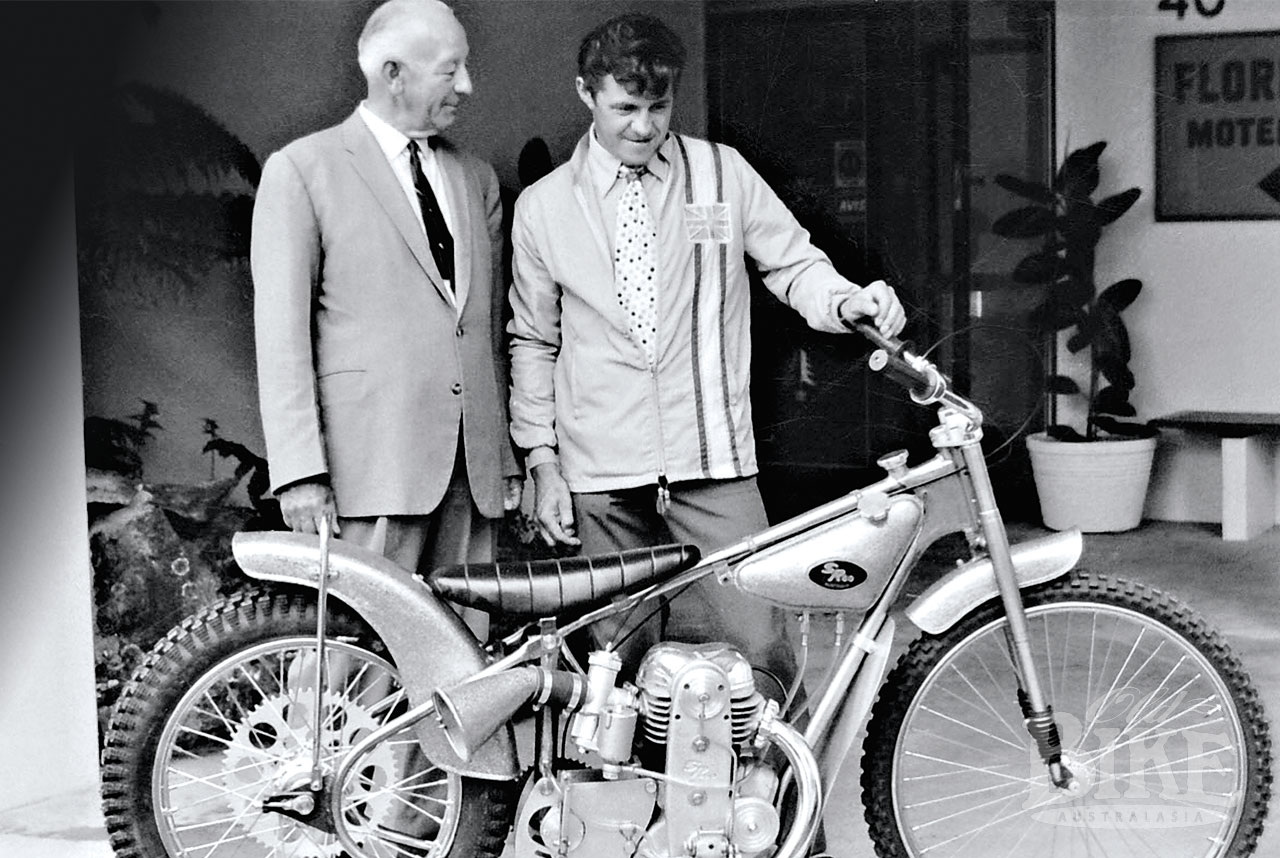

Keen to use the very strong A356 alloy Fred tried several foundries before he eventually found one willing and able to handle it. There was similar trouble finding fibreglass makers able to meet his high standards. Engine expert Len Dyson assembled the motors and his brother David did the machining. After the two prototypes were built, Fred envisaged the next step was for 10 bikes to be ridden by the 10 top riders in the world, followed by plans for around 300-400 machines to be made the following year.

Jolly had immense pride in the SR60. Pride that he had prepared a machine which was ready to take on the world, pride that it was made in his home town. His pride in the machine was second only to his confidence in it. In Fred’s words, “I have no fears whatsoever. I don’t care what anybody says – there has never been anything as good as the SR60 in speedway since I was a little boy. In fact never – I claim it is the best ever.”

Enter Len Dyson

When it came to transfer the ideas into metal, it was Len Dyson who did the majority of the engineering, as he recalled many years later.

“Fred Jolly came into my factory at Devon Park where I conducted an engineering and steel construction business. Up until this time I had been doing machining work for Fred and also mechanical work as required to his several speedway bikes. He had apparently got word that the ESO bike set up in Czechoslovakia was changing plans that somehow did not suit Fred who said he would not be handling Jawa speedway bikes any more. He asked me did I think we could successfully build an engine in Adelaide that would be as good as or better than the Jawa. After having a discussion about it I could see no reason at all that we could not design and produce an engine with several marked improvements to various design factors, and I guess it all started about there. The next move was to get something of the design on paper and this was done with the help of another very clever Adelaide business name, Harold Clisby (who built a 1.5 litre V6 engine for the 1961 Formula One). Harold and I spent many hours talking over the various design points that we felt could be improved upon. Harold did all the drawings at his place of business. Starting at the bottom we machined the flywheels from solid bar, surface ground, and jig-bored with all the necessary holes for the main shafts, crank pin (at 82 mm stroke) and balance holes. We used a parallel crank pin stepped similar to a Jawa but using a German caged roller bearing. The mainshafts were obviously of different design to accommodate the caged roller mains and the gear drive up to the overhead camshaft. The drive-side mainshaft however was redesigned completely away from standard practice used by JAP and Jawa. We made our drive side main shaft of large diameter and of one piece, with large double row needle caged bearing running directly on the shaft. This then protruded through the seal in the crankcases and was then machined with splines to suit the engine sprockets which were held on with two circlips – thereby removing the need for tapers, threads and nuts. The barrel was not the liner and muff type as on the Jawa, but simply one piece made from a nickel-iron compound machined and bored to standard 88 mm bore. The cylinder head was made a very clean design to accommodate a single camshaft.

The rocker arms were one piece with friction pad contact with the cam lobes and adjustment was effected by eccentric shafts. The valves and guides were same dimensions as Jawa. The overhead cam drive is by a train of gears running on needle cage roller bearings, hardened and ground pins in a fully enclosed aluminium vertical cover which could be removed complete with gears in situ. The top pinion mounted direct to the camshaft via a vernier, making timing a very simple task. The bottom end gear from the crank shaft also drove the pilgrim pump and via another gear to the magneto which was also a vernier adjustment. The magneto is mounted direct to the inside casting of the vertical drive cover and also came off as one piece. The connecting rod was of a design similar to a Carrillo in appearance and was considerably shorter than the standard Jawa rod. The two prototypes were all machined in either my factory or at my brother Dave’s machine shop as well as the motor assembly. The exhaust pipe was also hand made. Frames were made to a close copy of the Jawa frame by Rob Usher of Usher Exhaust Systems. Fred Jolly had patterns made and castings were done by Ellery’s foundry. Magnetos as fitted to the two prototypes were of the Lucas SR1 type.”

The end of the dream

With two prototypes built (one red and the other green) and a considerable sum of money invested, the next step was to actually market the bikes. During the 1974/75 Down Under speedway season, Danish World Champion Ole Olsen was persuaded to test the red SR60 at Rowley Park. Reportedly, Olsen was full of praise, although he only completed a handful of laps, and was keen to take the local machine back to England. But Jolly wasn’t ready for that just yet. He was still struggling with the marketing aspect and reckoned the SR60 would have to sell for about $1,000 – $200 more than the Jawa, and that 300-400 bikes per year was a realistic target. Alas, that was as far as the project went, and within a couple of years the design was out of date – swept aside with all the other two-valve versions by what became known as the Four Valve Revolution.

Fred eventually moved to Queensland, and when he died, the two SR60s became the property of his sister until they were sold in August 2003. The red bike, engine number 1, was purchased by Sydney speedway identity Alan Jones, while the green bike, engine number 2, went to Western Australia.