From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 89 – first published in 2020.

Story: Nick Varta • Photos: OBA, Elwyn Roberts, Keith Ward

What has one cylinder, three conrods, and can live with engines almost twice its size? The answer is an unorthodox looking little four stroke single produced by NSU from 1952 to 1963 – the Max, Spezialmax, Supermax, or in its ultimate, racing form, the Sportmax.

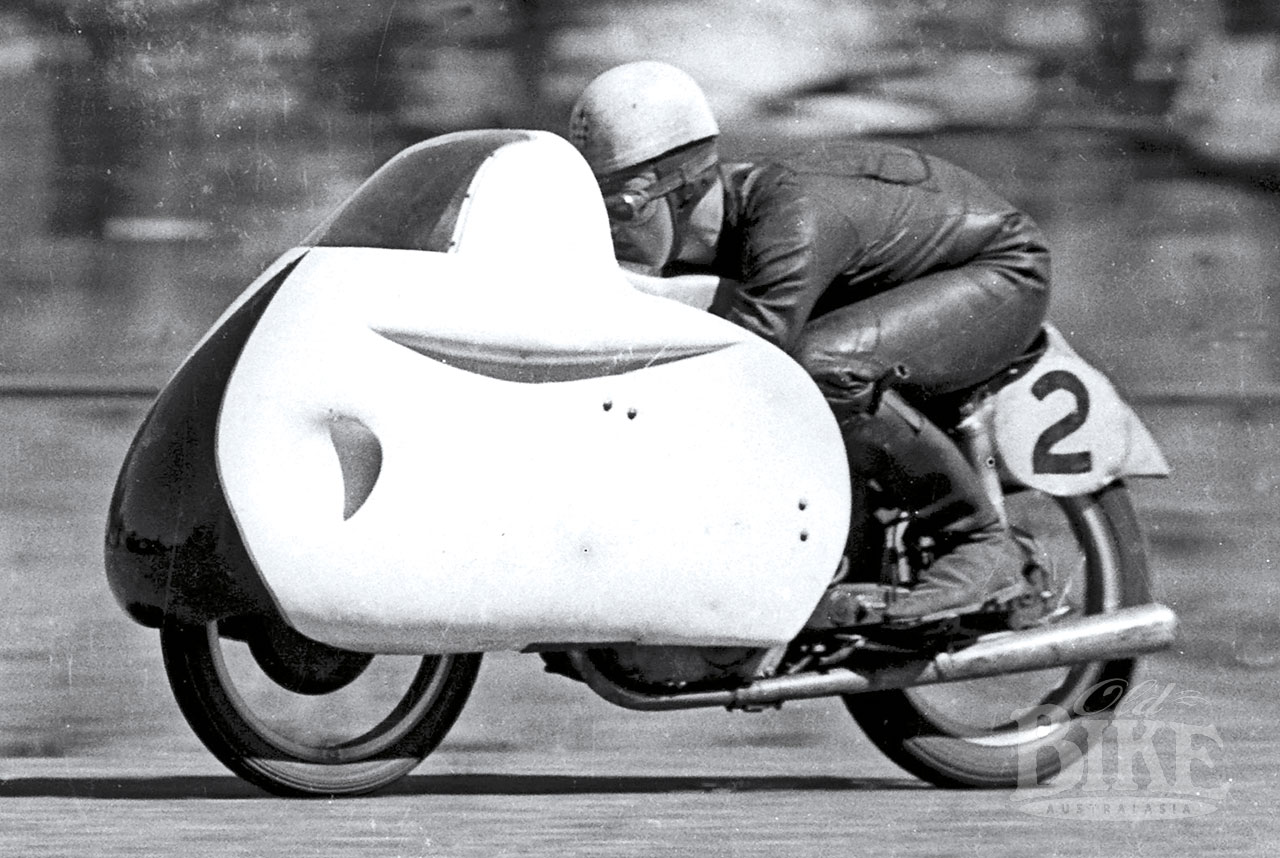

It would have been simple enough for a firm with the engineering nous of NSU – producer of the fabulous Rennmax twins that mopped up the 250cc World Championship for three consecutive years (1953- 1955), knocking the previously dominant Moto Guzzis off their perch – to pump out a conventional, affordable, reliable 250 for the average buyer. But no, what brilliant NSU engineer Albert Roder came up with was far from average.

The Max, first seen in 1952, wasn’t entirely new. Its chassis was basically that of the 200cc Lux that first appeared in 1951, but the power unit was unique; bristling with NSU’s characteristic eccentricity and of the quality of the famed pre-war 251, 351 and 501 OSL models. But while the Max was a triumph of engineering innovation, the sales department was scratching its head on how to price it within reach of the buying public, because the new 250 was extremely expensive to tool up for and produce.

The cost considerations were at least tempered slightly by the use of the up-scaled Lux frame; a deceivingly simple yet robust design in pressed steel, when tubular steel frames were becoming universal amongst ‘performance’ motorcycles. Trends and fashions aside, there was nothing much wrong with the pressed steel frame – even the works Rennmax racers used a similar system, albeit with a bolted on rear sub-frame to carry the rear suspension spring/damper units. However the main backbone frame on the original Max 250 was complex in that the centre section also housed the single rear spring/damper unit and its linkage, which was invisible from the outside, and very difficult to access should any work be required.

The Max rolling chassis was a multitude of steel pressings, from the headlight shell, front and rear mudguards, tool box and luggage compartment, battery case, luggage rack (which sat atop the rear mudguard in place of a pillion seat), the two halves of the main frame itself, the rear swinging arm, rear chain case and the front forks. Plus of course the petrol tank, various shrouds, and the long tapered muffler which was welded up from several sections.

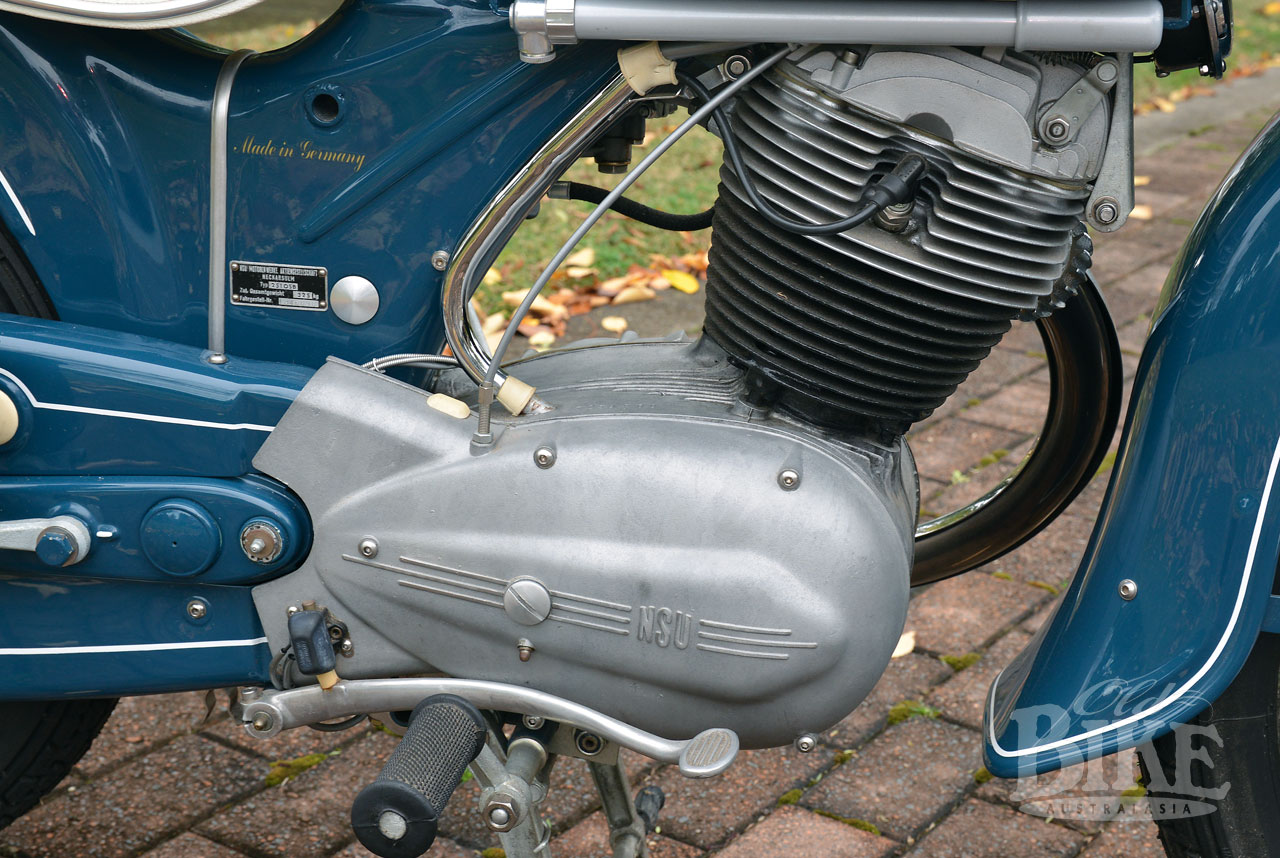

It was however, the power plant that really set the Max apart from its contemporaries. The specification listed vertically-split crankcases for the unit engine/gearbox, gear primary drive and dry multi-plate clutch, and a four-speed gearbox. The crankshaft rotated on roller bearings, with a Bosch 6 volt generator and the points for the coil and battery ignition located under the right side crankcase cover. The 26mm Bing carburettor and its air filter sat inside the centre frame section. Inside the cylinder head was a single overhead camshaft, large valves and hairpin valve springs. What broke with convention was the method for driving the overhead camshaft. The company called this the Ultramax system – another clever idea from Albert Roder. The entire system was cleverly concealed in a tunnel on the left side of the engine. From the crankshaft, a second shaft, running at half engine speed, drove a pair of connecting rods (like conventional conrods but with big ends at both extremities), to timed eccentrics in the cylinder head. As the engine heated up and expanded, the camshaft was able to rotate slightly around its axis. Valve clearances and other settings were thus maintained regardless of engine temperature, which was fortunate, because a simple tappet adjustment required removing the engine from the frame. The Ultramax system is also extremely quiet in operation, with none of the clattering or whirring associated with bevel or chain driven overhead camshafts.

The system was used on the Max series motorcycles, from 125cc to 297cc, the Maxima 175cc scooter, and from 1958, on the NSU Prinz cars. Between the two and four-wheelers, almost one million engines were made using the Ultramax system. However the British were quick to point out that Bentley had used a very similar arrangement on their six-cylinder cars in the 1920s! Bentley’s less sophisticated system replaced the vertical shaft camshaft drive with a method whereby a crank-driven bevel gear turned a small triple-throw crankshaft, which connected with a similar crankshaft on the cam, operated by a set of three connecting rods.

The first of the 250 MAX models (officially called the 251 OSB) appeared in late 1952, mainly for the home market, and were initially available with a sprung Pagusa rubber saddle for the rider (hinged from the front and sitting on a vertical coil spring enclosed in the frame), and either a pillion pad or pressed steel luggage rack fixed to the rear mudguard. Later, a plush Denfeld dual-seat was available, which had a steel base with small linked springs and an upper cushion of foam rubber with a vinyl cover. First versions of the 247cc Max were fitted with small-diameter single-sided cast iron drum brakes, but when exports began in force about 1954, the model, marketed as the Spezialmax, was produced with seven-inch full-width alloy hubs, and a 3 gallon fuel tank replacing the original 2.25 gallon. To gain social acceptance in an era when adverse publicity surrounded motorcycling and motorcyclists, great attention was paid to quietness, but without sacrificing performance. The substantial muffler, which contained an intricate series of baffles, was developed by NSU and does an exceptional job of muffling the combustion process efficiently.

As well as the 250, a special 297cc version was produced for the Austrian market only. This came about due to punitive tariffs for all imported motorcycles below 275cc in Austria, introduced to protect local models, particularly the split-single Puch. These ‘Three-hundreds’, officially known as the 301 OSB, or unofficially as the Austria MAX, have become extremely desirable and command very high prices. The ‘300’ was achieved by enlarging the bore from 69mm to 72mm and the stroke from 66mm to 73mm. Compression ratio was up slightly, from 7.4:1 to 7.6:1, and power subsequently increased 4 PS to 21 PS (20.7 hp).

Unfortunately, the 297 was not sold in Germany, as it would have required a full “Class 1” motorcycle licence, whereas the cheaper Class 4 licence allowed riders to operate motorcycles up to 250cc. Taxes and insurance were also more expensive for over 250cc bikes. These days, the rare 300s are prized for their ability to haul sidecars.

By 1955, NSU was officially the largest (by volume) motorcycle company in the world and set about giving the Max a makeover for 1956. NSU addressed the power question in a different way. Rather than increasing the engine capacity, it increased engine efficiency and performance for the new Supermax, which squeezed out 18hp at 6,500 rpm. Negating this somewhat was an increase in weight; from 165kg to 174kg, but the new model was still good for a worthwhile 126km/h top speed, 10 km/h up on the Max.

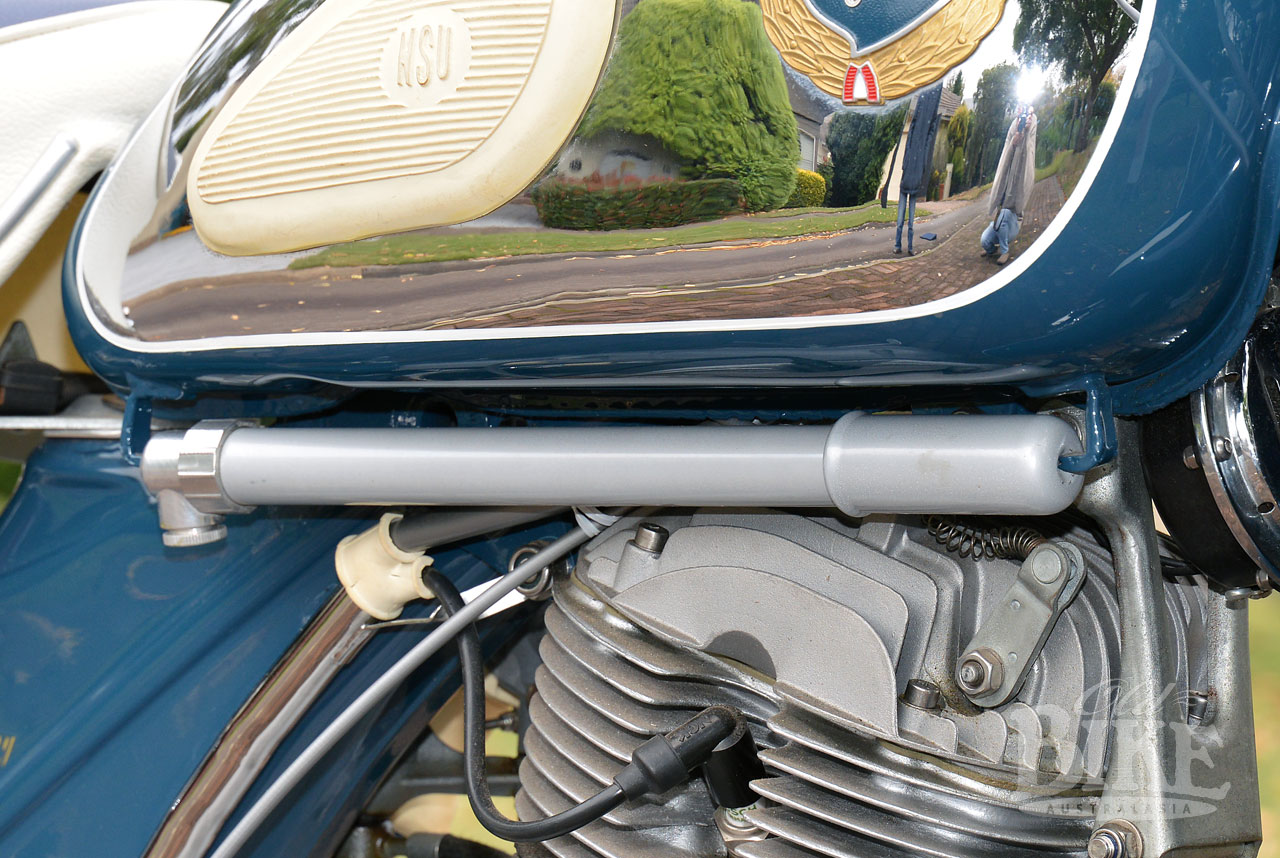

The new Supermax, which appeared in 1956, bowed to convention by having the linkage-operated single shock system replaced by a pair of conventional shock absorbers mounted on the swinging arm and forward of the pillion seat. Apart from little niceties such as a steering damper, the new model was otherwise virtually identical to the earlier ones, but never achieved the same sales volume. By this time, Germany’s economy had substantially recovered from the post-war austerity, and the buying public was clamouring for cars, not motorcycles. Whereas around 80,000 of the first Max models were made, only 15,473 Supermax models were produced from 1956 to 1963, when NSU ceased making motorcycles.

To address the problem of the high retail price, NSU even considered having the 250s built by Vincent in England, using parts shipped from Germany. There was also an arrangement with the Swedish Monark company, which imported engine/gearbox units and built them into their own chassis – a scheme that lasted just one year, 1957.

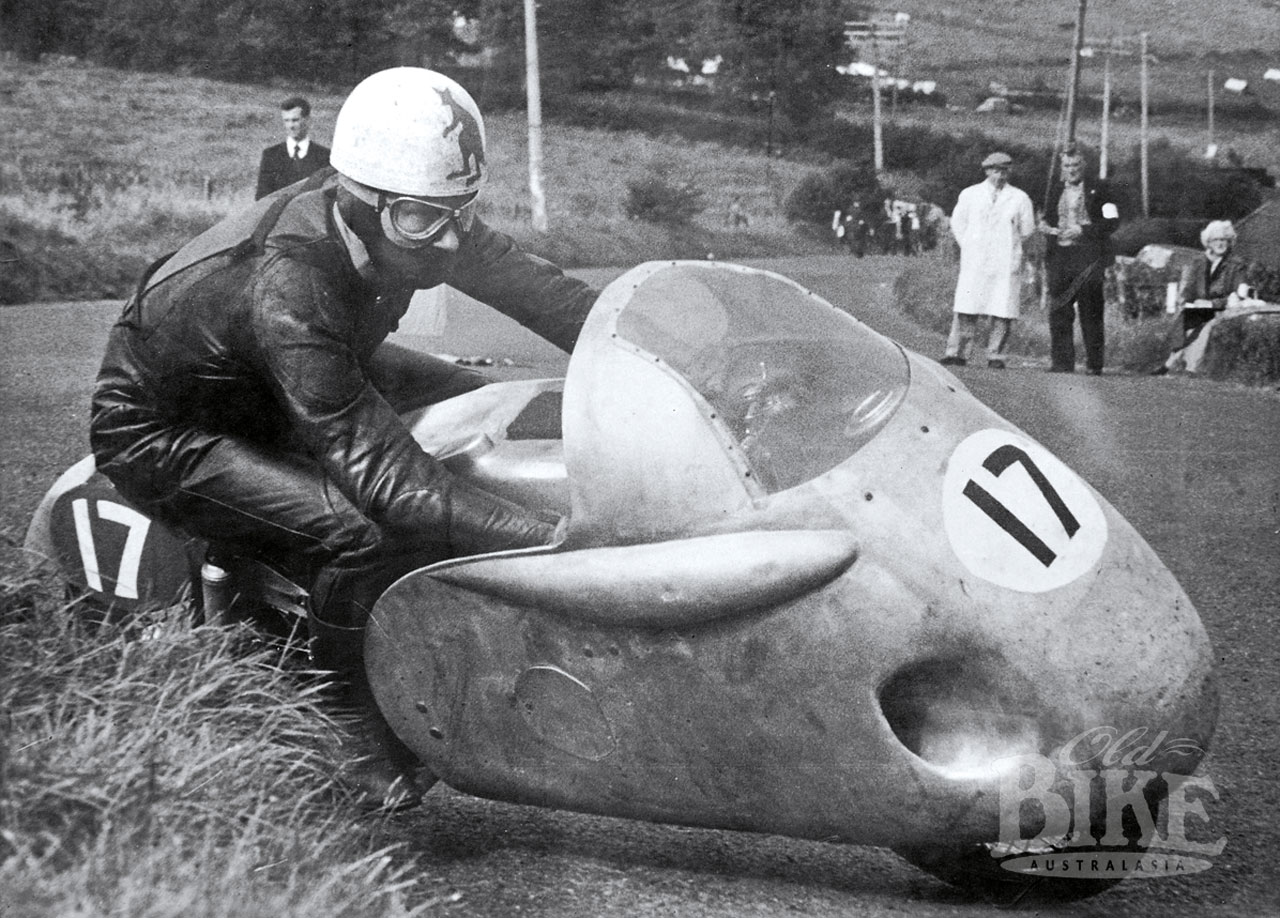

There was in fact one other version on the Max theme, the limited production Sportmax. These were designed purely for racing and were highly prized for the few riders able to afford them or secure one from the small yearly allocation. The Sportmax engine was identical to the Supermax, with the exception of the cam profile and compression ratio. The main differences, apart from the larger carburettor and exhaust system were in the area of weight saving by the use of aluminium for the fuel tank, mudguards and wheel rims, and a larger twin-leading-shoe front brake. It was a fine package at a time when the privateer tackle in the 250 class still consisted mainly of pre-war designs, and these machines were highly successful in the hands of John Surtees and later Mike Hailwood. Australian privateers Bob Brown, Eric Hinton and Jack Forrest also got their hands on a Sportmax and used them very effectively both at home and abroad. The little singles were still winning many years after production ceased and were a match for many 350s. Forrest also managed to buy one of the 297cc engines and used it in his Sportmax briefly until it blew up. He said however that the ‘300’ was no faster than his 250, and far less reliable.

In 1957, Jack Ahearn took the Sportmax that had been imported by Hazell & Moore in Sydney, to a stretch of straight road at Barradine, near Coonabarabran in western New South Wales, where he set up a new Australian Speed Record for the 250cc class with a speed of 121.252 mph (195.14 km/h). To give an idea of the speed of the 250, Ahearn’s new record on his 350cc Manx Norton was only marginally better at 125.68 mph (202.3 km/h).

Following the winding up of motorcycle production in 1963, NSU concentrated on cars, and formed a joint venture with Citroen to develop the Wankel rotary engine. Most major car manufacturers purchased a licence to build Wankel rotary engines from NSU, which produced its own version, the NSU Ro 80. This was very expensive to tool-up for and produce, and was a sales disaster, crippling the company. In 1969, NSU was swallowed up by the Volkswagen Group and became part of the Auto Union combine, along with recently-acquired Audi. Production remained at Neckarsulm, with the front-engined Porsche 924 and 944 also built there. The Ro 80 was produced until 1977, when it, and the NSU name, was finally laid to rest.

Our featured motorcycle is a 1957 Supermax which was originally sold new in San Francisco, USA. This accounts for a number of small features peculiar to US models, including the high-rise handlebars (with longer control cables) and the turning indicators fitted at each end of the bars. It is also fitted with the optional Denfeld dual-seat. Owner Jack Cairns is quick to acknowledge the considerable assistance he has received from Wolfgang Schneider of NSU Classic Motorcycles in Germany, who has been the marque specialist for decades. While Jack’s Supermax is complete and running, he has a second project on the go; an earlier Spezialmax with the single-shock frame.

Specifications: 1957 NSU Supermax

Engine: Single cylinder, rod-driven OHC with 2 valves per cylinder.

Bore x stroke: 69mm x 66mm

Capacity: 247cc

Compression ratio: 7.4:1

Gearbox: 4 speed

Power: 17.5 hp at 6,800 rpm

Top speed: 126 km/h

Carburettor: Bing HD 2/26/55

Frame: pressed steel

Suspension: Rear: swinging arm with dual spring/damper units.

Front: pressed steel with internal spring/damper units.

Tyres: Front and rear 3.25 x 19

Brakes: 160mm drum front and rear.

Dry weight: 174 kg

Fuel capacity: 14 litres