In that Shangri-la for classic bikes, the NSW Northern Rivers area, long-time Norton fan and OBA contributor Michael Robinson has fallen for a big twin.

This is not the story of an amazing restoration, of raising another ‘chook shed Lazarus’ from the dead or finding the last rare part of a mechanical jigsaw puzzle under a diprotodon hide in a native Patagonian hut. Rather, it’s about one man’s search for the ideal classic machine, one that combines tradition, character, exhilarating performance and head-turning looks in a motorcycle that makes both riding and ownership deeply satisfying.

Pat Holt is an eminently practical man: an automotive engineer, businessman, dedicated social cricketer (despite being in his mid Fifties) and several times president of the Northern Rivers Classic Motor Cycle Club, situated in the far north eastern corner of N.S.W. Pat is an avid rally rider and tourer, most often with wife Brenda sitting up behind.

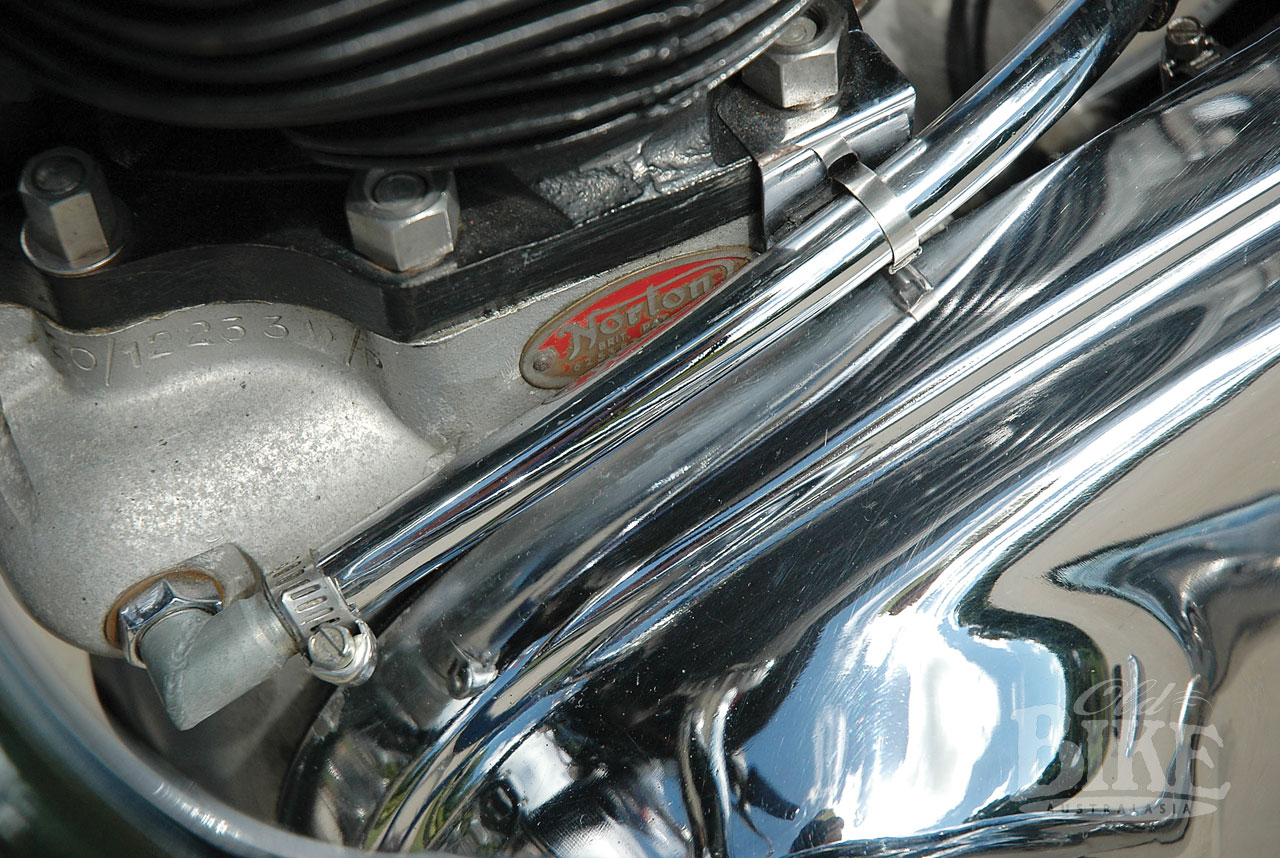

His workshop, neat as a new pin, is home to three quite perfect Norton twins. Why Nortons? Pat acknowledges the beauty of old Triumphs, appreciates the quality of BMWs and even concedes that the Honda 750 Four is probably thelandmark motorcycle of all time. However, he believes that Nortons have five attributes that, combined, overshadow all the others: superb handling, sturdy manufacture, reliable performance, classic good looks and ease of maintenance. As a testament to his careful restorations, none of his machines have the normally ubiquitous drip trays under them.

Two of the Nortons are 500cc Dominator 88s that saw service as Military Police mounts in the Royal Air Force in Malaya. They were brought to Australia from Penang by a couple of RAF Flight Sergeants after the Communist insurgency abated in the late Fifties. (Apparently it was British military policy to leave nothing behind in abandoned overseas postings, nor to bring old equipment back to Blighty. However, if one had mates who flitted about the general area in Hercules cargo planes…!)

Pat purchased one of the 88s and restored it to original specs., painting it the most glorious dark RAF blue – the same paint that was used on the tail wings of RAF Mirage fighter jets.

Pat got used to classic road riding on the Blue’Un but soon found he wanted to go a bit faster than the mild mannered little twin would allow. An article in Classic Bike magazine on the building of a café racer inspired him to convert the second of the RAF Dominators into something rather more sporty. He found its frame and most of the main hardware in the NSW coastal town of Woolaweela.

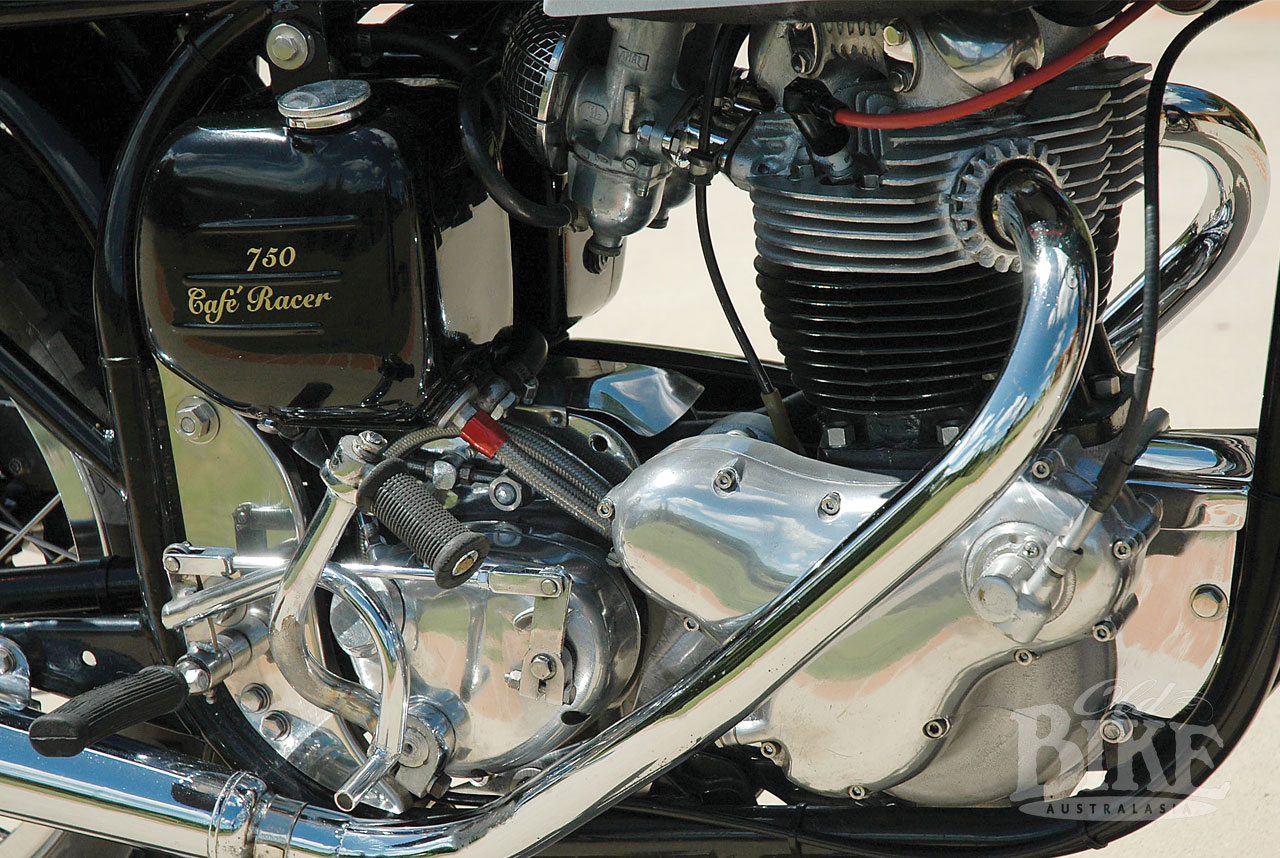

Pat says that he extensively modified the original 500cc motor by including second-hand 750cc Commando barrels that were sleeved back to standard, an Atlas head, Atlas crankcases, Commando crankshaft, 650SS camshaft polished and the whole unit balanced by Waggott. The inlet tracts were milled out to 30mm and the 1.5 inch long manifolds were made from high tensile steel to prevent heat transfer from the head to the two 30mm Amal Concentric carburettors. (Quite what remains of the original motor is a moot point.)

When asked why he didn’t simply replace the 88 motor with an old Commando unit and avoid cobbling together such an amazing amalgam of disparate parts, Pat explained that, unless a Commando motor leans forward, the oil pickups are left high and dry. Furthermore, the Commando motor was balanced at 50% so that it rocked backwards and forwards to make the Isolastic engine mountings work effectively. Paul Dunstall suggested that the balance would have to be changed to 72% if it was to be mounted rigidly, and inclining the motor forward required quite different engine plates to a standard motor. Therefore it wasn’t a simple matter at all.

Boyer ignition, electronic voltage control, swept-back pipes, Commando mufflers, blade guards and a sparkling fibreglass tank from British firm Unity Spares complete the very handsome picture.

One anomaly is that the twin leading shoe front brake is on the left side of the machine. It requires an expert eye to identify the backing plate as a Honda 450 unit, which was milled to neatly fit the Norton drum. Pat lauds the Honda brake as vastly superior to the original Norton stopper in quality and strength of manufacture, and in its operating function. He made this modification when unable to track down an original Norton part. Those lucky enough to be offered a ride on the café racer are seriously forewarned about this brake’s tremendous stopping power.

The positioning of the clip-on handlebars is most ingenious. They were originally located on the fork tubes under the top triple clamp but created a riding position not recommended by chiropractors. To overcome this, Pat had two pieces of solid alloy bar fashioned with hexagonal sections and threads at the bottom ends to fit into the tops of the fork tubes. He then attached the clip-ons above the hex sections, giving a much more acceptable riding position. The only problem was that the pylons could be turned by the handlebars and come loose in the fork tubes, with obviously dangerous results. To keep the pylons static, Pat contrived two alloy plates with hex holes in them that fit exactly over the hex. sections of the pylons. These are then held in place with nuts and bolts that pass through the lobes at the front of the locking plates and into holes in the sturdy alloy bracket that mounts the instruments. Problem cleverly solved.

The café racer is a beautiful machine in looks, ingenuity and performance (upward of 60bhp).

One would think that Pat had the best of both worlds with these machines but two incidents made him think otherwise. Firstly, while riding the Blue ‘Un solo, he was passed going up a long, steep hill by a Commando with two rather large people on board. That in itself wasn’t all that remarkable but another time he was passed going up a similar hill on his café racer by another Commando with two up. That did surprise him and he decided it was time to find one for himself. He and his wife are committed participants in Alpine Rallies and the like, and the old Dominator simply didn’t have enough puff to make long rides together an easy experience. A Commando would change all that.

The choice of model wasn’t straightforward. Being a methodical man, Pat weighed up the options. The 750 Fastback was a good-looking machine with almost as much speed as later, larger-capacity Commandos and the optional 750 Combat motor actually developed more horsepower than an 850, though it had a propensity for blowing the bottom end to pieces. (Perhaps that fault could be rectified with modern technology.)

The 850 Interstate Mk. IIA was of first interest; a 6 gallon touring tank, an inordinately long seat for two-up comfort, most of the former Commando problems sorted, a strong bottom end running in Superblend bearings, crankcases reinforced with internal webbing and a nice clutch.

Pat concedes that the Mk. 3 was probably even better, with rear disc brake, adjustable Isolastic suspension and electric start but, at that stage, Norton was obliged to change the gearshift over to the left side to satisfy the American market, which meant a change in gear shifting pattern from one up and three down to one down and three up. Pat was disinclined to have a bike whose gear change was the opposite of his other Nortons and so opted for the Mk. IIA.

A few people of Pat’s acquaintance who owned motorcycle retail businesses tried to coerce him into purchasing modern machinery, and though Pat rode them and appreciated them, nothing was so overwhelmingly superior as to excite his interest. His main objection was that one could do little if not nothing to them and he likes to tinker, considering that to be one of the greatest delights of motorcycling. He also likes the motor to be on display.

“I checked out a new MV Augusta recently,” he commented, “a $65,000 bike, and you couldn’t see anything past the red paint.”

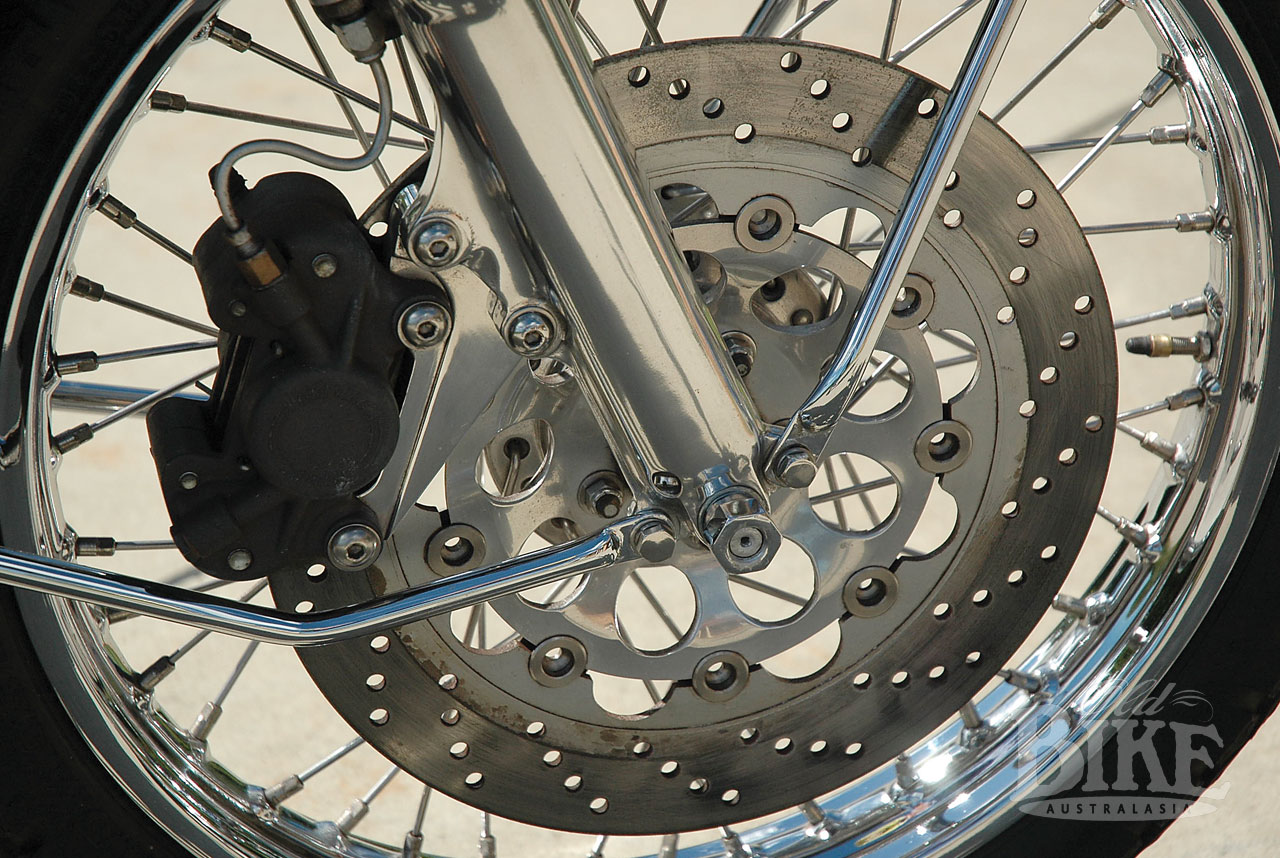

When Pat got hold of his Commando, he promised his wife he wouldn’t spend time riffling with it but, untrue to his word, he immediately pulled it down. Having come from a seaside town, the alloy was corroded, the stainless steel mudguards pitted and the chrome was rusty. These problems were quickly rectified and while apart, he had the inlet tracts polished and the cam ground to S4 specifications to give more torque to a motor already possessing tremendous pulling power. The crankshaft journals were polished, bearings replaced, pistons and con. rods balanced, and stainless fasteners employed. He fitted it out with Boyer ignition, voltage control, a massive aftermarket 13 inch full floating disc with Grimeca calliper to replace the original Girlock, a small cast-iron disc of dubious provenance. These, with better oil lines and clamps, better oil filter and air filter, help to realise the full potential of what was a great idea not all that well realised in its original form and imbued a thirty year old machine with modern reliability.

The only obvious additions are the disc brake assembly and the genuine Norton steering damper, which Pat claims takes some out of the wriggle out of the steering, a characteristic of the Isolastic engine mountings that isn’t present in his two Featherbed models. He also chose to install factory rear sets which alter the riding position to one Pat obviously prefers (a la the café racer). This set-up halves the downward travel of the brake pedal compared with the standard one, so Pat had the rear brake actuating arm lengthened by 50% to compensate.

Up until the Mk. 3, this vaunted feature could be adjusted only by shimming, which was a tedious day-long effort, especially as the rear mountings necessitated removing the swing arm to adjust them. Norvin of England now supplies for all earlier Commandos the much simpler system that came with the Mk.3. and Pat has changed over to it. One simply loosens off the centre bolts through the Isolastic mountings, tightens up an inner pin-located nut until there’s no play, backs it off one half turn, relocates it with a pin and re-tightens the centre bolts. The job is done in ten minutes.

The Norton Commando was assuredly the best English motorcycle of the day. It was perhaps the last staggering leap forward while the rapidly diminishing number of classic British machines in production was having the curtain rung down upon it. That Commandos won the European ‘Motorcycle of the Year’ for five years in a row is probably more testament to lack of competition than overwhelming superiority.

Pat argues that, with the exception of the Honda Four, the Kawasaki 900 and perhaps a very small handful of others, Japanese motorcycles are not contenders for the title of classic bikes. Production runs are short-lived and the obsession with radical updating and endless model changing precludes them from a noble lineage.

Pat has ridden many, many motorcycles, both old and current, but reveres and loves his Commando beyond all others. “I’m completely within my comfort zone from 30mph to 110mph, whether solo or with Brenda on the back, whether on a five day rally or cruising down to Bryon Bay on Sunday morning for a coffee,” Pat says with a grin. “People wave at me as I go by and when I pull up, a crowd gathers. Try that on a modern Jap bike.”

A very good idea has been turned into a great idea and the Norton legend lives on in day-to-day reality.