Story Jim Scaysbrook and Lars Glerup • Photos Independent Observations, James Jubb, Antony Gullick, Gaven Dall’Osto, Michael Andrews.

Honda has built over 100 million variants of the C100 Step Through. Yet in a manufacturing life of 40 years – from 1919 to 1959 – Nimbus built just 12,715 examples of their four-cylinder motorcycle. Less than one per day.

Perhaps that’s because its creator, or more correctly co-creator, Peder Andersen Fisker, was a technician who dabbled in engineering merely as a hobby. It was a collaboration with Hans Marius Nielsen, who also hailed from Copenhagen, Denmark, that led to a business venture in 1906 involving an electric motor the pair had built. That motor was refined and adapted to power the first European vacuum cleaner, the Nilfisk, which was produced from 1910 and which was patented by Fisker. Nilfisk is today a global identity in the cleaning business but by 1919, Fisker and Nielsen had a new venture going – a motorcycle.

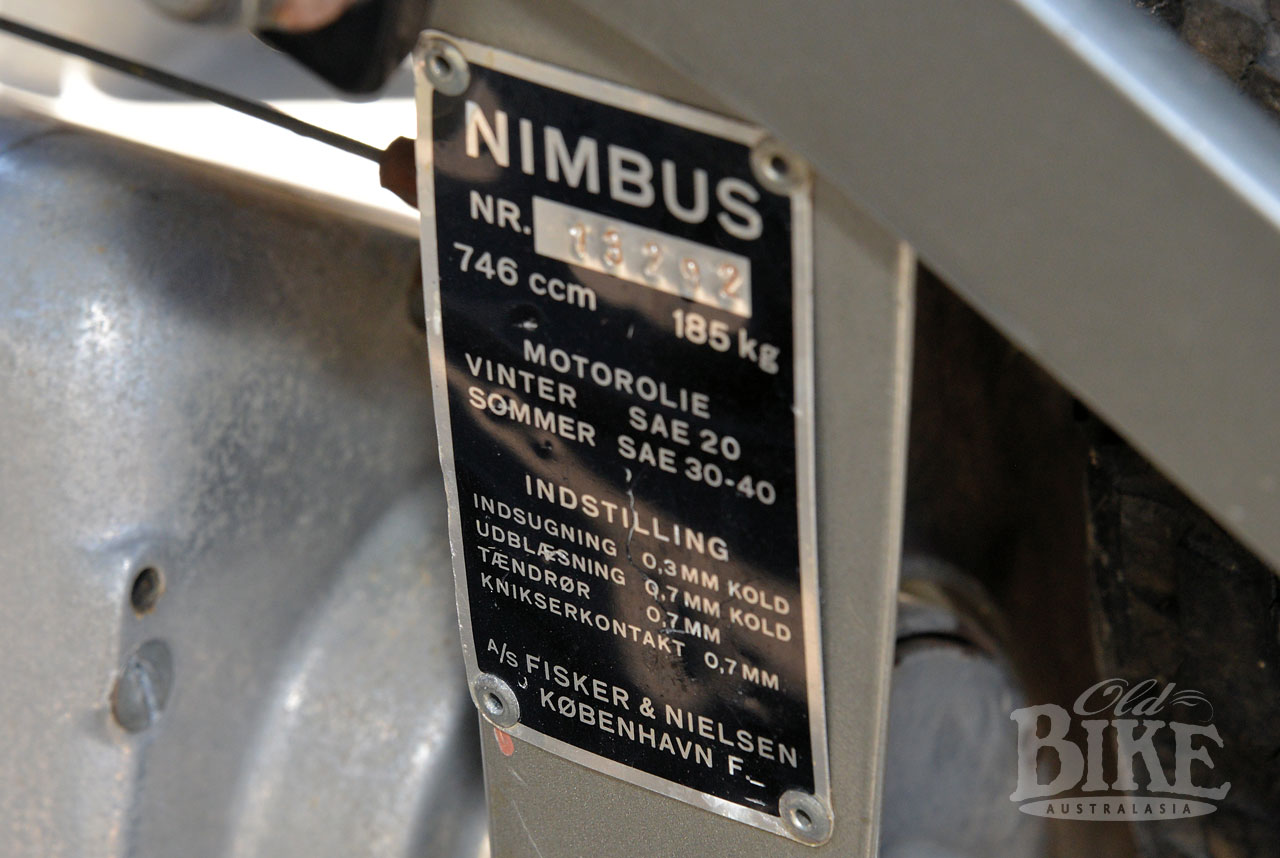

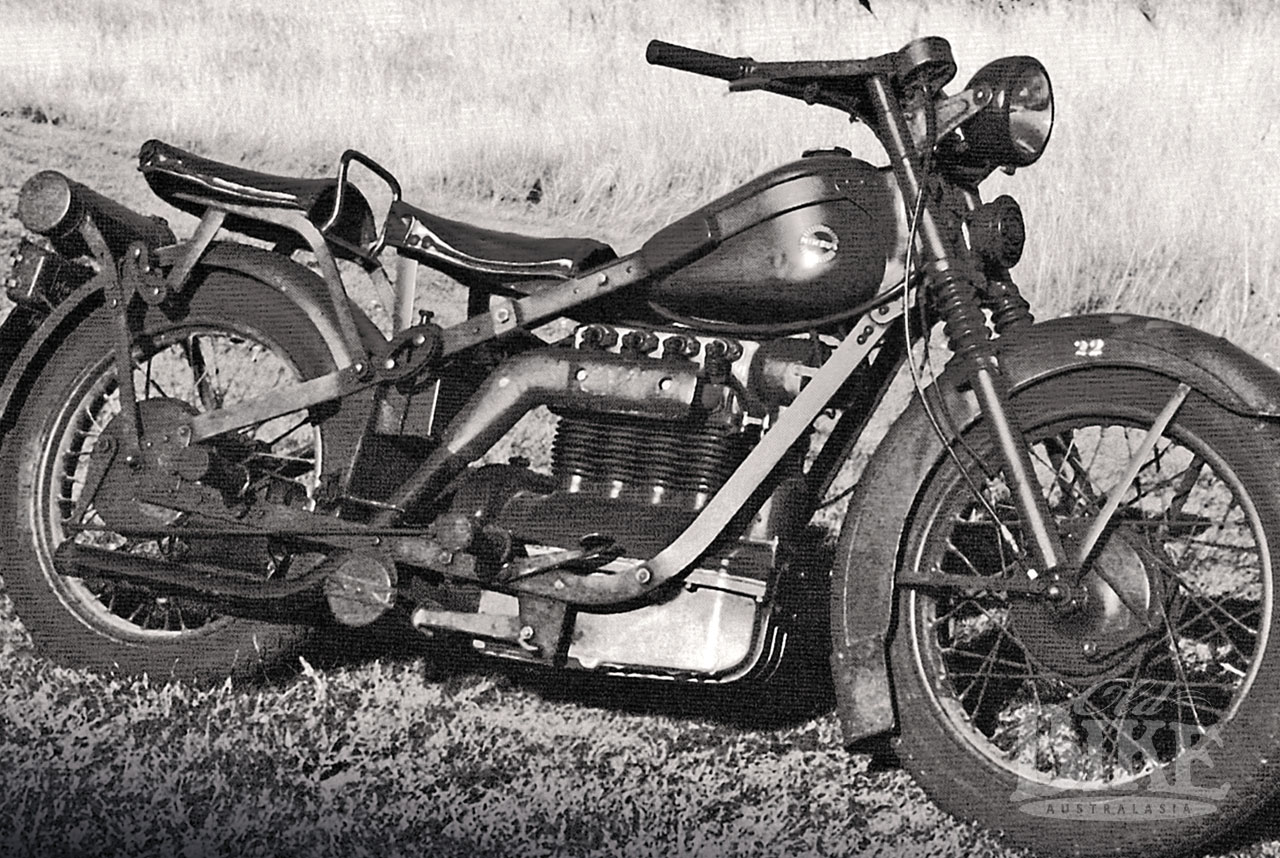

This was no flimsy start, no bicycle-based motorised two-wheeler. The first Nimbus (named after the luminous clouds often depicted in illustrations of saints and other holy beings) used a 746cc four-cylinder engine with bore and stroke of 60mm x 66mm, shaft final drive, three-speed gearbox and a pressed steel welded frame with sprung suspension at both ends. A novel feature was the large diameter top frame tube which doubled as a petrol tank, leading to the nickname ‘stove pipe’. The Nimbus poked out about 10 horsepower with a top speed of approximately 85 km/h.

To say production was slow is a major understatement – just two were completed during 1919 and ten the following year – but the buying public took a shine to the machine and demand encouraged the partners to embark on a redesigned model that was released in 1923. The update included a new type front fork and a more efficient carburettor. However Nimbus, and other manufacturers, was hard hit by the introduction of a sales tax on motorcycles in 1924 which severely flattened sales. At the same time, sales of the Nilfisk vacuum cleaner were going through the roof, and the decision was taken in 1928 to cease production of motorcycles after some 1,200 had been made. The vacuum cleaner business boomed to such an extent that a new factory was built.

Fisker wasn’t finished with motorcycles however, and he now had an empty factory at his disposal. Working with his son Anders, a new Nimbus was created in 1934, called the Type C. The basic specification remained, but the 746cc engine now had the valves actuated by an overhead camshaft. Like conventional car and aircraft engines, the upper half of the crankcase and the cylinders were cast in one, with the lower crankcase half being a an aluminium oil sump. The one-piece cylinder head incorporated an inlet manifold with exhaust valves on the right and inlets on the left, each automatically lubricated. An aluminium camshaft housing was bolted to the cylinder head, carrying ball and socket bearings for the rockers. At the front, the vertically-mounted camshaft formed the armature spindle for the dynamo, with the gear-type oil pump at the lower end. Coil ignition was used with automatic advance and retard, the contact breaker sitting in a casing bolted to the camshaft housing. The camshaft itself was a single drop forging running in two large diameter ball bearings. At the rear of the crank sat the flywheel which incorporated a single plate clutch. To this was bolted a three-speed gearbox which was hand-operated for the first two years of production, with an optional foot-change available from 1936. The drive shaft ran from the left side of the engine to the rear wheel. A piece of forward thinking that would later become quite commonplace was the funnelling of exhaust blow-back collected in the crankcase up to a chamber connected to the carburettor. As well as producing a cleaner running and more efficient engine, this also lowered crankcase pressure and eliminated (or perhaps reduced) leaks from oil being forced out through gasket joints.

The frame was completely new; made from sections of flat steel, welded and riveted together, with the top tubes wrapping around the conventional petrol tank. Up front was a telescopic front fork (preceding BMW), although hydraulic damping was not incorporated until 1939. The rear end was rigid. Despite the four-cylinder engine, all-up weight was just 172kg.

Fisker and son set up a strong dealer network for the new product and the Type C went on sale in mid-1934. It was soon nick-named the Bumblebee due to its distinctive humming exhaust note. Success was instantaneous and the Nimbus gained valuable sales through the Danish police, Post Office and eventually the army. With equally healthy civilian sales, the Nimbus quickly became the biggest selling motorcycle in Denmark. The basic Model C remained in production until the end, being subtly refined along the way. A heavier front fork came along in 1936, along with beefier brakes, in line with the machine’s favouritism as a sidecar hauler.

Series production concluded in 1954, but motorcycles continued to be assembled in small numbers until 1959, using accumulated spare parts. Military models accounted for almost 20 per cent of the total made in 40 years. As late as 1972 the Danish Post Office still ran the Nimbus, and the Danish Marine Force continued even longer. Very few Nimbus motorcycles were exported, although some were sold in Africa and a smaller number in America and eastern Europe. The majority of the 12,000-odd made are still in existence, thanks to the efficient spare parts supply.

A family Nimbus

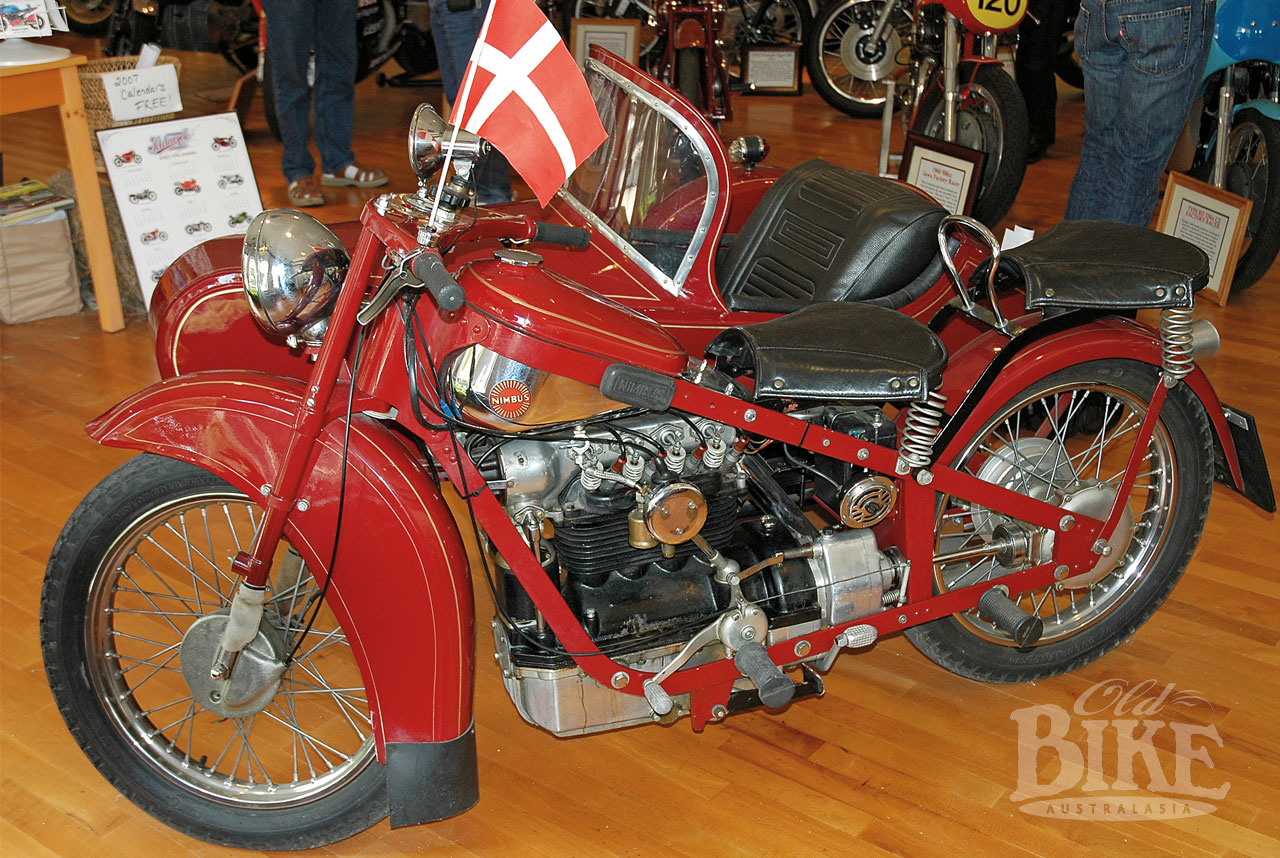

Despite never being officially imported, there are quite a few examples of the Nimbus 4 in Australia, including the featured model here, owned by Grant Evans. This machine holds an affectionate place in the Evans household, as it was the vehicle on which newly-married Grant and Nicole left their wedding reception 25 years ago. This one is a 1945 model, which Grant purchased from Danish immigrant Steen Hermanason. “I actually rebuilt a red Nimbus for Steen, a 1943 model, and bought it off him, then later sold it back to him, “ explains Grant. “Then he imported this one from Denmark and put a sidecar on it, so eventually I convinced him to sell it to me.”

On patrol: Nimbus in the Danish Army

When the Danish army had to make the decision as to what the ‘standard’ motorcycle had to be, the Army Technical Corps were mainly leaning towards buying motorcycles from outside of Denmark. However after tests with many different brands of motorcycles, it was the Danish Nimbus that was chosen. The Danish army bought its first Nimbus in 1920, a “Stovepipe”, and another one the year after. It was not due to local patriotism that the Nimbus was selected. In fact, there were many who had pushed to buy the big American motorcycles such as Indian and Harley-Davidson or the British single-cylindered machines. Many thought that the Nimbus, with its four cylinders, was fragile and not strong enough to pull a sidecar.

When the Nimbus, A and B models went out of production in 1928, many of the top brass in the army were happy, for now they could buy the motorcycles they really wanted; Norton, Douglas, BMW, BSA and single and twin cylinder Harley-Davidson models, and a few other brands. It was successful in the beginning but the first problem for the foreign brands was overheating when riding in convoys at low speed, and many of them spent a lot more time in the workshop than the Nimbus ever had done.

In 1932, a new Army Act had passed through parliament and that also meant a lot more funds for the army. The top brass had decided that it was time to leave the horses in the paddock and get the army personnel motorised. This was also the year where Civil engineer, Anders Fisker, had convinced his father, and the board of Fisker & Nielsen that it would be profitable to develop and manufacture a new Nimbus, the Model C, if production could reach 1,000 units per year. The army had decided it would develop all-new motorcycle squadrons. In 1933 the army began very long and systematic tests of various brands of motorcycles, but the new Nimbus almost missed out on being considered, as it wasn’t ready until the beginning of 1934. It was first presented to the press on 20th of April 1934. The Danish army took delivery of its first three Nimbus on the 30th of June 1934.

The tests revealed very quickly that the choice would be between the Harley-Davidson VL, 1,200cc and the Nimbus with only 746cc. The Harley was very heavy and if it became bogged, it was a struggle even for two men to get it free again, and the antiquated ignition system and carburettor adjustment made it difficult for untrained people to start the bike. The Nimbus was lighter, and the ignition retard and advance were automatic and there was no carburettor adjustment either, which meant that it was an easy machine to start without any prior training. Before the final decision was taken, the army mechanics were asked their opinion. They all said that the American bikes were more difficult to repair and maintain than the Nimbus. One major point was that the Nimbus has no chains to be looked after. Also, the frame construction is so much simpler and a job as simple as changing the front fork is so much easier on the Nimbus. After all the pros and cons, the decision for the army’s ‘standard motorcycle’ ended up being the Danish-manufactured Nimbus.

In the late ‘thirties the Nimbus was, yet again, up for comparison with other brands of motorcycles, this time it was the German brands, BMW and Zündapp, the technology of which had come a long way in a very short period of time. BMW and Zündapp were constructed to the most modern concepts, whereas the British and American brands were unchanged. BMW and Zündapp had now as well as Nimbus, gone for the outside frames and shaft drive. The BMWs were, from 1935 onwards, fitted with oil-dampened telescopic forks, whereas Zündapp still had the pressed steel trapeze forks. The engineers at Zündapp also stuck with a gearbox that had internal chains instead of the more controversial gearbox with pinions. Even though the German brands were very good, it was decided to retain the Nimbus, as it had proven to be a very robust machine in the previous 5 years. The threat of war from over the border may also have had some influence.

In 1939-40 the Danish army had a total of 487 motorcycles of various brands for its disposal. In that year all the motorcycles travelled together a mere 2,287,526 km; an average of 4,697 km per motorcycle. In order to keep a better record on costs, a costing calculation was made, based on amortisation and operating expenses such as petrol, oil, tyres, repairs and maintenance for the different brands of motorcycles. In the financial year of 1939-40 the army’s average cost per kilometre for a motorcycle was 20 cents. If the costs were set up to compare the different brands of bikes, the Nimbus had the lowest cost of only 8.04 cents/km, Harley-Davidson 9.80 cents/km, Norton 15.00 cents/km, BSA 17.50 cents/km, Ariel 21.60 cents/km and the most expensive, the Douglas at 24.12 cents/km. The figures speak for themselves. There was no doubt in keeping the Nimbus made good sense.

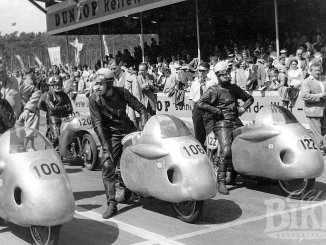

At 4.15 am on Tuesday morning, 9th of April 1945, German troops started what was called ‘’; the combined attack on Denmark and Norway. The purpose was for the Germans to secure one of Denmark’s air force bases in North Jutland. It also gave the Germans the ability to access the North Sea very easily. On the Danish side of the German/Danish border fighting began early that morning and a number of Nimbus with 20mm machineguns mounted in the sidecar came into action and made quite substantial damage to the German troops. However the Danish Government decided to surrender as their army had no chance against a 40,000-strong German army, plus Luftwaffe and Navy. The Danes lost 16 soldiers and 23 were wounded that morning, while the Germans casualties were much higher.

With the war on the production of Nimbus came to a bit of a halt. Fisker & Nielsen with P.A. Fisker in the Director’s chair had absolutely no intention to make anything to benefit the Germans, as they were very interested in the motorcycle production and the size of it. F & N did, in fact, very deliberately, create confusion in its books of the Nimbus production, in order to keep the Germans away. In the years 1940-45 only a very limited number of Nimbus were manufactured, and they were only for civilian use. As petrol became rationed and only issued to doctors, ambulances and fire brigades, etc., it put a brake on selling Nimbus motorcycles. It also became harder and harder for F & N to get raw materials, and things such as tyres became almost impossible to get.

After the German capitulation in Denmark on the 4th of May 1945, where Field Marshal, Bernard Montgomery signed the surrender with the German armed forces in North Germany, Holland and Denmark, it was announced via BBC Radio, London, that same evening. Denmark could cheer again and so could F & N, as the Nimbus manufacturing could recommence. It took some time before F & N was back on its feet and it was not until the 19th of April 1948 that the Danish army received its first delivery of 200 Nimbus following the war. When Denmark became a member of NATO in 1949 and also because of the cold war, the army placed some big orders with F & N. It was 100, 200 and sometimes 300 Nimbus at the time, as well as a large number of sidecars.

The big orders from the army did, in some ways, create problems for the civilian market. In the ‘fifties, Nimbus dealers country-wide were asking for more deliveries than F & N could supply, and all production to the civilian market was stopped for months when the orders for the army had to be completed. Unfortunately, the good times for F & N’s Nimbus production had eased off by the end of the ‘fifties and in 1957 F & N announced that the production would cease by the end of 1959. The last Nimbus motorcycles were sold to the army in March 1960. From 1934 until 1960, the Danish army had bought a total of 2,329 Nimbus motorcycles.

The total number produced in the same period was 12,715 which meant that the Danish army had bought approximately 20% of the entire production. Due to the announcement of cessation of production, the army had set up a contract with F & N to supply spare parts for the next 15 years. In the first couple years after the production had ended, F & N also overhauled a large number of Nimbus motors. That arrangement then went to a private engine machine-shop in Jutland, which overhauled up to 150 motors per year for the army. In the end, not much money or effort was spent to keep the bikes going. If there were major problems with, for example, the motor, gearbox or rear bevel gear, another Nimbus was used for spares. Thus, many of the ex- army Nimbus have no longer matching engine and frame numbers.

In the late ‘sixties and early ‘seventies, the Danish army started to decommission its fleet of Nimbus motorcycles. It was done by auction and the Nimbus was sold in bundles of 10 machines at the time. The bidding was very low and often only reached the scrap metal price. It was mostly Nimbus dealers who bought them and then restored and painted them in civilian colours. The left-over spares from the army were also sold by auction, often in large boxes on pallets. The bidding was on a whole pallet at the time and yet again it went for scrap metal prices. The replacement for the good, old, trusted army Nimbus was the British BSA B40. The joy with them was rather short-lived as they spent more time in the workshop than on the road, so it happened often that the few Nimbus which were still in depots around the country’s army barracks were dusted off and yet again pressed into service. That meant that in the late ‘seventies, Nimbus could still be seen being used on army exercises. I remember from my time in the Danish army, 1977-80, that the BSAs we had spent more time in the back of a truck than on the road. The BSAs were replaced in the early eighties with two-stroke Yamahas, but then in 1989, the army came to its sense and bought BMWs!