The world’s first and second motorcycle 24 hour races produced heroic performances, amazing endurance, and tragedy.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Dennis Quinlan, Graeme Osborne, Todd Hamilton, OBA archives.

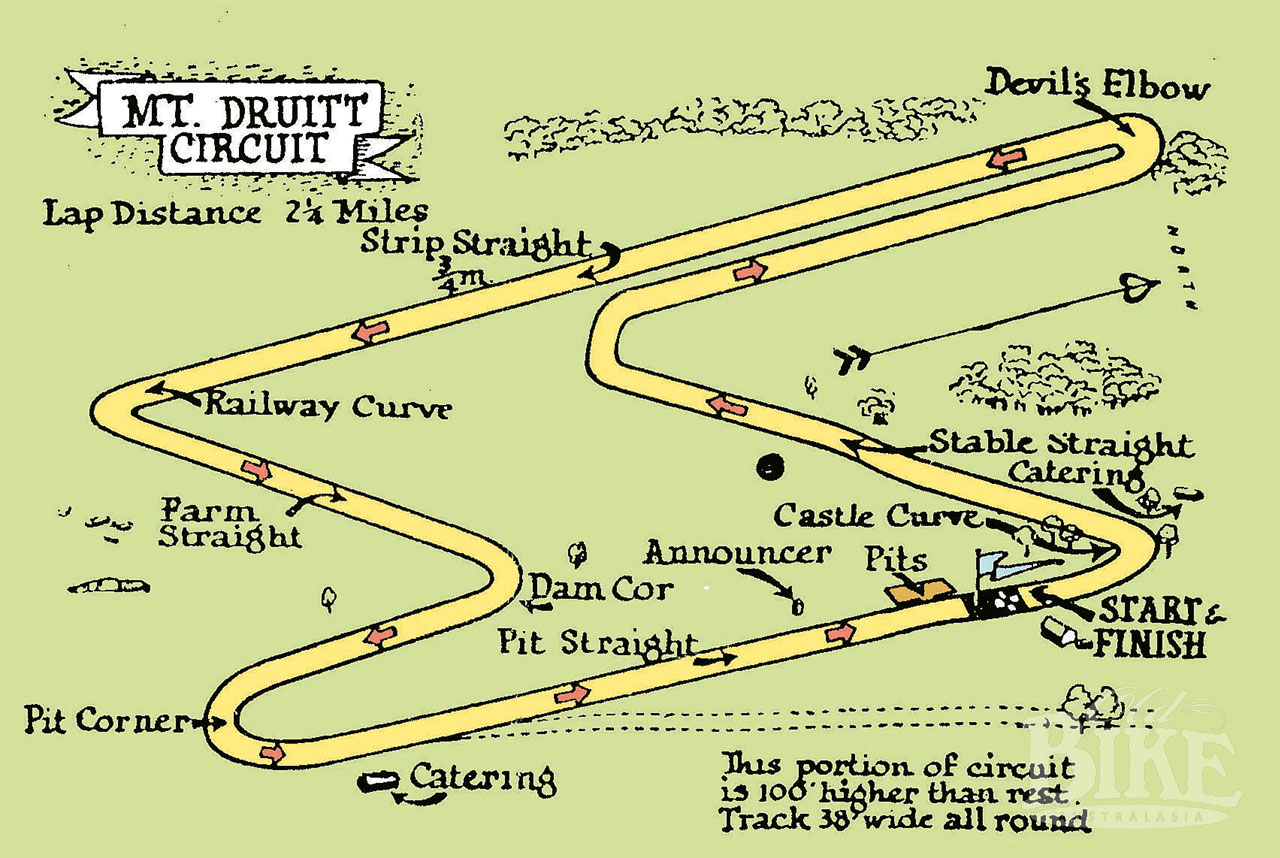

Rugged and devoid of facilities it may have been, but the Mount Druitt circuit in western Sydney was never short on promotional acumen. The former wartime airstrip had been converted from a straight up and down squirt with U-turns around oil drums at each end, into a proper and popular 3.6 km circuit that utilized the strip plus a loop road running to the top of the hill (where Whalan Public School now stands) and back down the other side.

From the opening motorcycle meeting on November 16, 1952, the track became the Mecca for road racers whose only other venue in the state was the once-a-year Mount Panorma meeting at Easter. The lease holder was the flamboyant Belfred Jones, a lively Welshman who ran a company called Speed Promotions which had its office in the grand but dilapidated mansion, Centenary House or simply ‘The Castle’ that stood on the crown of the hill. The circuit hosted a packed calendar of car and motorcycle races, but Jones was always looking for something different, and borrowing an idea from Le Mans, France, promoted the first 24 hour race for production cars to be held in Australia, beginning at 2 pm on January 31st and concluding on February 1st, 1954. Complete with the obligatory ‘Le Mans’ start, the race attracted 22 entries and was won by the Queensland team of Bill Pitt, Chas Swinbourne and Mrs Geordie Anderson in her Jaguar XK140 hardtop. The race was not without its problems, among them an almost total lack of crowd control and the gradual disintegration of the track surface, and was not repeated, but Jones refused to give up on the idea and instead, hawked the proposal around the motorcycle trade for a round-the-clock race for standard production bikes.

Motorcycle sales at this point were in free-fall, dropping by almost 50% in the 12 months to June 30, 1953, and the industry was willing to try anything to arrest the decline. But by the time the date for the proposed event came around on the 1954 October Long Weekend (3rd and 4th) things were even worse and much of the promised trade support failed to materialise. Determined to go ahead, Speed Promotions put up a total of £1,000 prize money.

After the destruction caused by the cars, the circuit was patched up, but The Auto Cycle Union of NSW was wary and refused to grant a permit until a large number of safety issued were addressed. The idea of racing in the pitch black (the circuit had no permanent illumination) on machines with rudimentary lighting was daunting enough, but there were other problems as well. Piles of rusting wartime junk had to be carted out of the long grass surrounding the track, and some attempt at containing the livestock was also made.

Light my fire

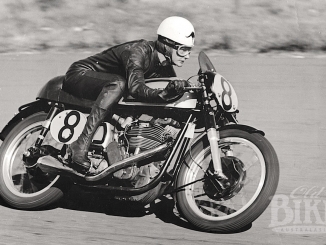

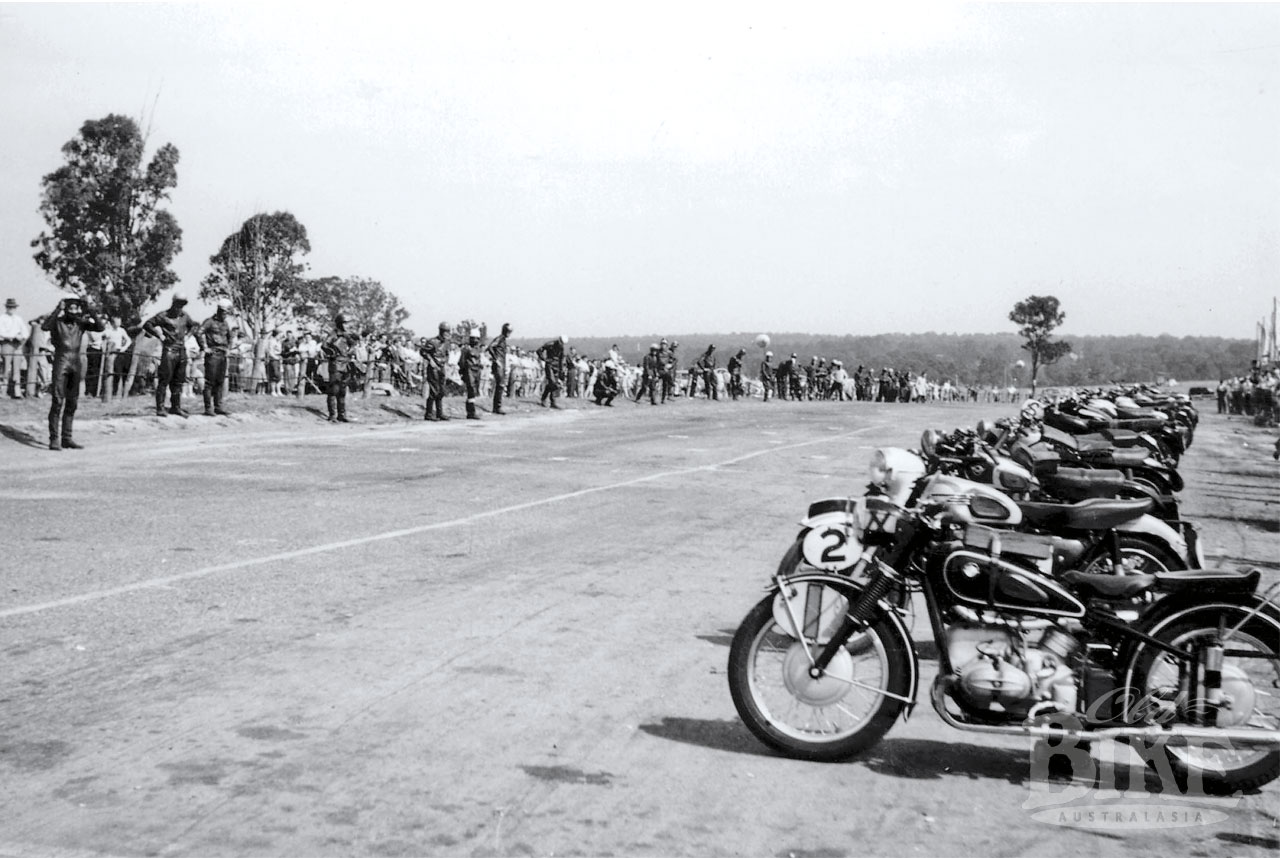

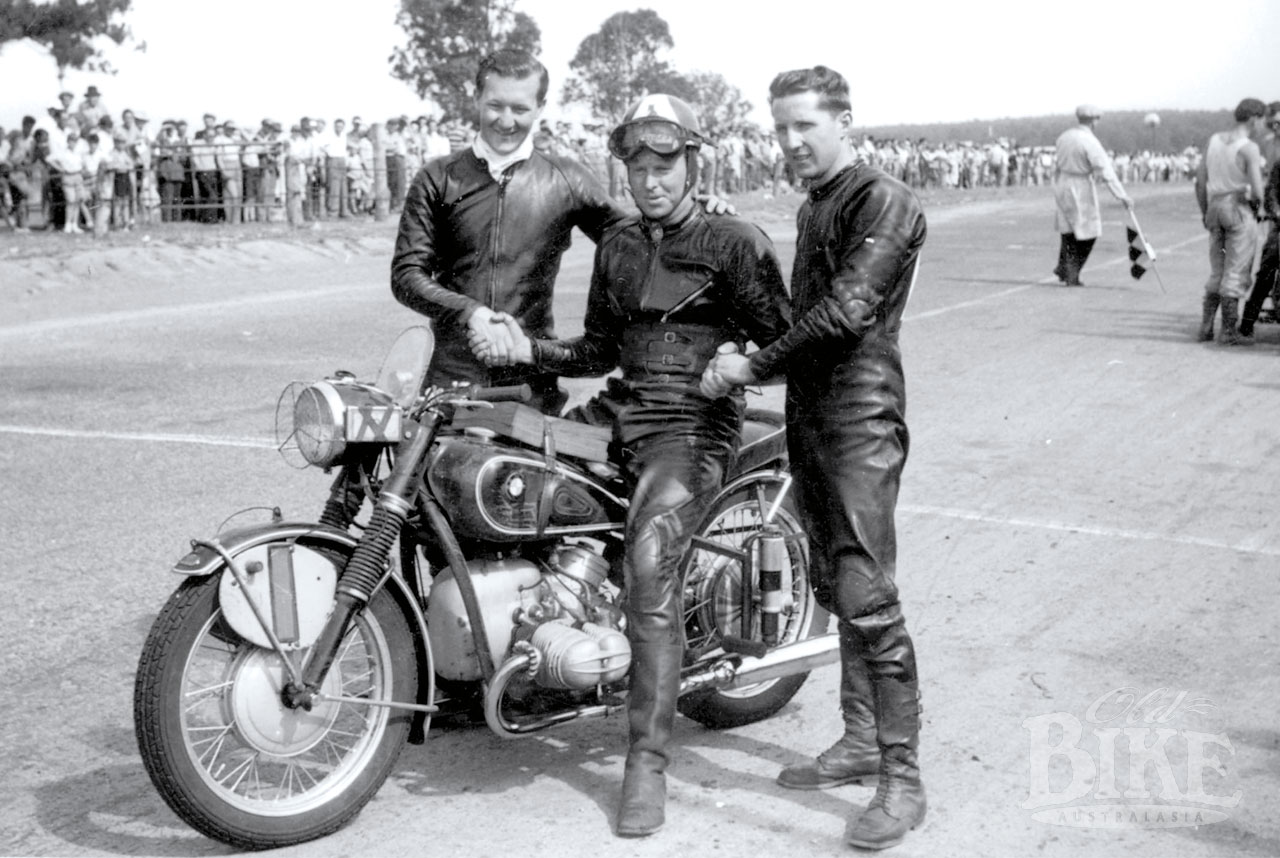

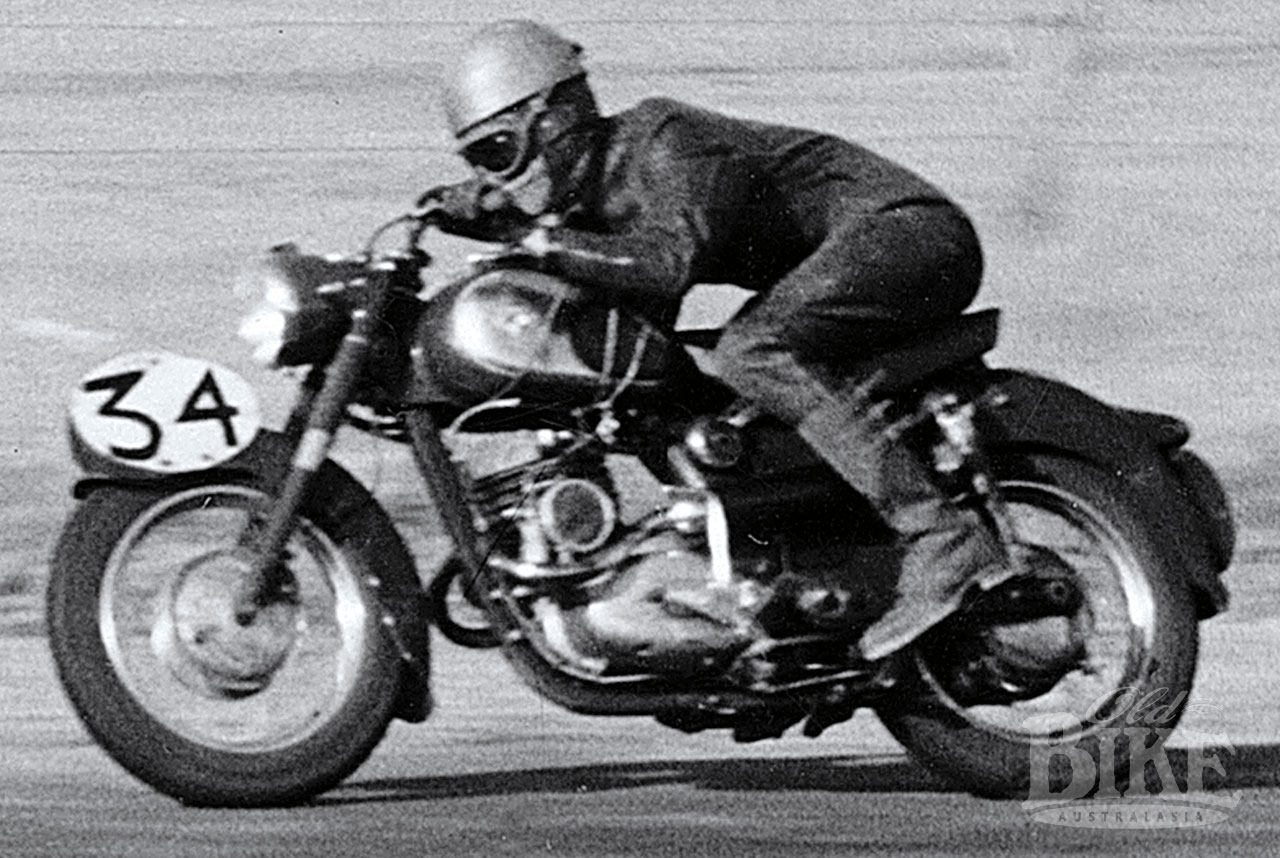

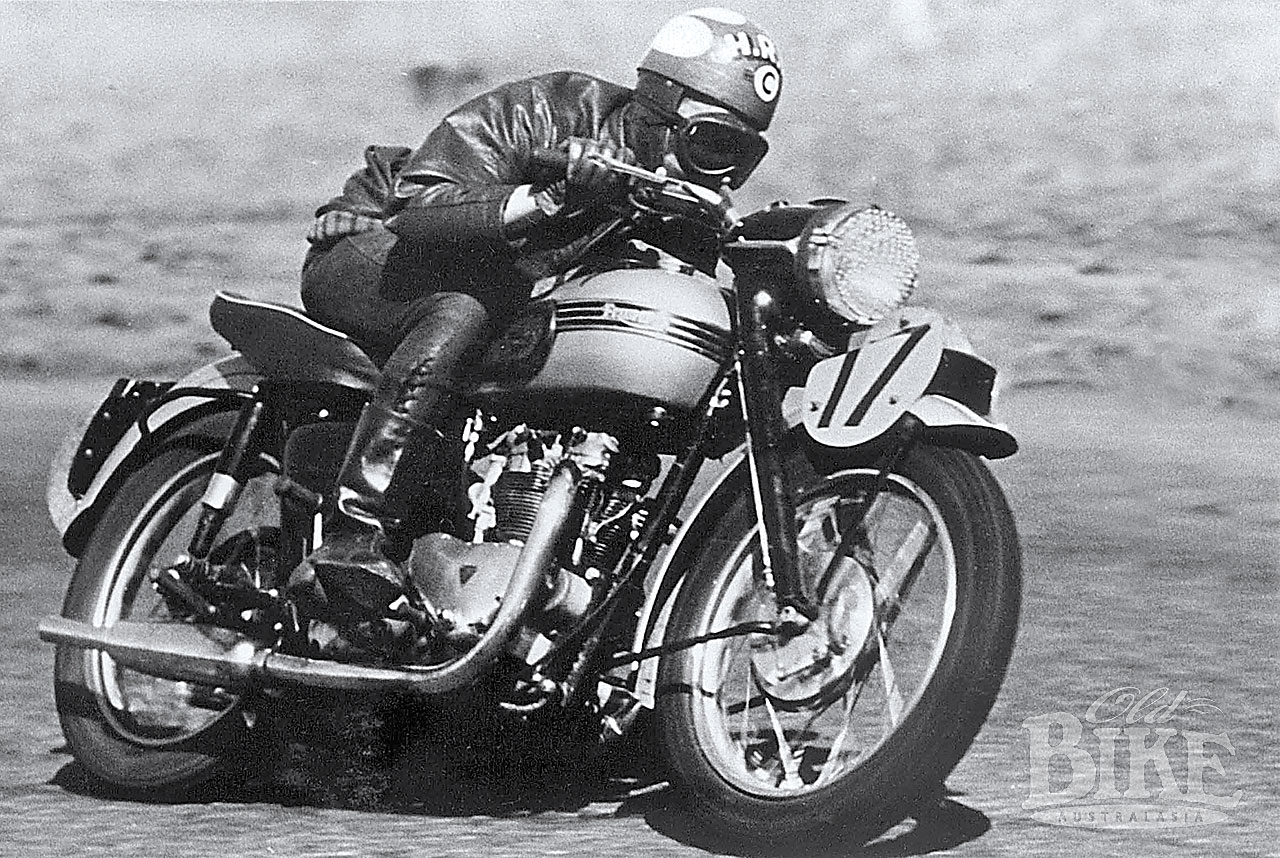

Eventually a permit to stage the race was issued, but when entries closed there were only 32 nominations and the proposed 125 cc, 250 cc and Sidecar class entries were pooled into what was called the Combined Class. The Junior class was for motorcycles from 256 cc to 355 cc, with the bulk of the entries in the combined Unlimited and Senior class. Pre-race favourite was the 500cc ‘Featherbed’ Norton International ridden by Harry Hinton and his sons Harry Junior and Eric, but a strong challenge was expected from the new BMW R68 entered by Jack Forrest. Forrest was naturally the lead rider, but he needed two others to form the team, which had the support of NSW BMW distributor Tom Byrne.

“I was employed as a salesman at Tom Byrne’s shop in Wentworth Avenue at the time,” recalled Don Flynn in 2001, “and was having some modest success with the 350 Norton I had bought from Jack Ahearn, and was asked by Tom if I would be interested in joining Jack Forrest’s team for the 24 hour race. Forrest was a successful used car dealer with a yard at Parramatta Road Auburn, and was also a star in the motorcycling world and I guess we were all a bit in awe of him. After he checked me out I was offered the ride, and when Jack asked me if I could suggest a third I put forward my pal and fellow member of Parramatta Motorcycle Club, Len Roberts. Although Tom (Byrne) was a sponsor of the team he did not supply the bike. This was Forrest’s machine which he had bought when the first shipment of BMWs arrived. They had a big reputation – thoroughly deserved as it transpired – for excellence of workmanship and reliability; an area where British machines were sadly lacking at the time.

Don Bain, a star rider of pre war days was Byrne’s workshop boss and was appointed as team manager. Bainy’s attention to detail and meticulous planning were to be a big part of the team’s success. Practice for the event was, I think, held on the Wednesday and Thursday prior to the race and when the big day arrived we had honed our refuelling and rider changes to a nicety.”

From the Le Mans start at 2pm, Forrest’s BMW shot to the lead, with the Hintons in close pursuit. At 4pm, Flynn took over the BMW for his two hour stint, maintaining the handy lead. As darkness fell the area took on an eerie look with the headlights flashing around the circuit, which had only a few hurricane lamps for illumination. The only electric lighting consisted of a few lights scattered around the pit area and in front of the lap scoring stand. Inside the pits, a small village of tents housed sleeping competitors and a refreshment stall.

The first real excitement came at 11.45 pm when a cow strayed onto the course at the sweeping downhill bend that led onto the airstrip, just as the 500 AJS ridden by Tommy Farr arrived at full speed. Farr struck the animal and was thrown off, the tumbling AJS being collected by Barry Halliday and Errol Thurston. With the track virtually blocked, the race was halted for 20 minutes to allow the wrecked machines and the cow’s carcass to be removed. Farr was uninjured but Halliday and Thurston both went to Parramatta Hospital, the former with both wrists broken and the latter with a dislocated jaw. Incredibly, the race was briefly halted one hour later to remove another cow from the course, luckily before anyone could hit it.

The Hinton team’s Norton had its generator fail early in the piece, forcing the team to change batteries at each fuel stop. At 1.15 am, the Norton pitted for refuelling, having covered 281 laps, but a spark from the battery terminals ignited leaking petrol and in a trice the lot was engulfed in flames; the tank exploding spectacularly. With no fire extinguishers on hand, the Norton completely burnt itself out, briefly illuminating the pit area!

“I can recall that I was riding at the time”, said Flynn, “and saw the flames in the Hinton pits area leaping skyward as they consumed our only real challenger. After that we were always comfortably well in front and it became an armchair ride with the BMW performing superbly”.

At dawn, the BMW R68 team of Jack Forrest, Don Flynn and Len Roberts was a clear leader, but the Triumph Thunderbird entered by Arnold Glass’ Capitol Motorcycles and ridden by Keith Bryen, Barry Hodgkinson and Bill Tuckwell was clawing back ground, with the G9 Matchless ridden by Keith Conley, Keith Stewart and Sid Webb not far behind. When the chequered flag went out at 2 pm, the BMW had covered 648 laps, or 2,330 kilometres, at an average speed of just over 60 mph, with 19 laps in hand over the Triumph. Winners of the 500 Class were established road racers Conley, Stewart and Webb on the Matchless G9 twin that Stewart had ridden to victory in the 2,500-mile Redex Trial just weeks previously. BMW also took out the Combined class (with riders Don Bain, Jack Humphries and Wal Hawtry aboard a 250cc single cylinder R25) on 547 laps, while Bruce Rands’ Norton outfit was the sidecar winner on 461 laps. The Junior class went to the AJS ridden by the McLeay brothers and Max Alexander on 530 laps. For the Outright and Unlimited class victories, the Forrest team collected £220, or about the price of the motorcycle. 23 of the original 32 starters made it to the finish.

“The BMW factory were ecstatic and invited the team members to visit the works in Munich as their guests,” said Don Flynn. “Lennie (Roberts) and I were poor working boys in hock to the eyeballs to keep our Manx Nortons going and would have been flat out affording the fare from Parramatta to Sydney let alone to Germany. Forrest however had no such problem and went off to be met and feted at BMW and was provided with the latest Rennsport to do the Continental circuit. Jack brought it back to Australia – a wonderful machine and much admired here, although he had more success I think with a 250cc NSU which he also imported from Germany.”

Despite the dramas, and the disappointing turnout of spectators, the event had impressed the struggling motorcycle trade, and BMW in particular made much mileage of the win – their first in International racing since the war. Although the 24 Hour scarcely covered costs, the promoters immediately laid plans for a bigger and better event, with the date set for the weekend of October 29/30, 1955.

Horse on the course

The second running catered for four capacity classes; Up to 250 cc, 350 cc, 500 cc and Unlimited, while the sidecar class (which had attracted only three starters in 1954) was dropped. To acclimatise riders to racing in the dark, a special practice session was arranged for the Wednesday evening prior to race weekend. While lighting had been improved somewhat, the security of the track precinct itself had not. Early in the night, a horse strayed onto the track just as Len Roberts was reeling off some laps on the new Don Bain-entered 600 BMW. Swerving to avoid the beast, Roberts was thrown off at top speed and died from multiple injuries before he could be transported to hospital. As a mark of respect, Bain’s BMW and 250 Adler teams were withdrawn from the event, leaving 38 teams to face the starter.

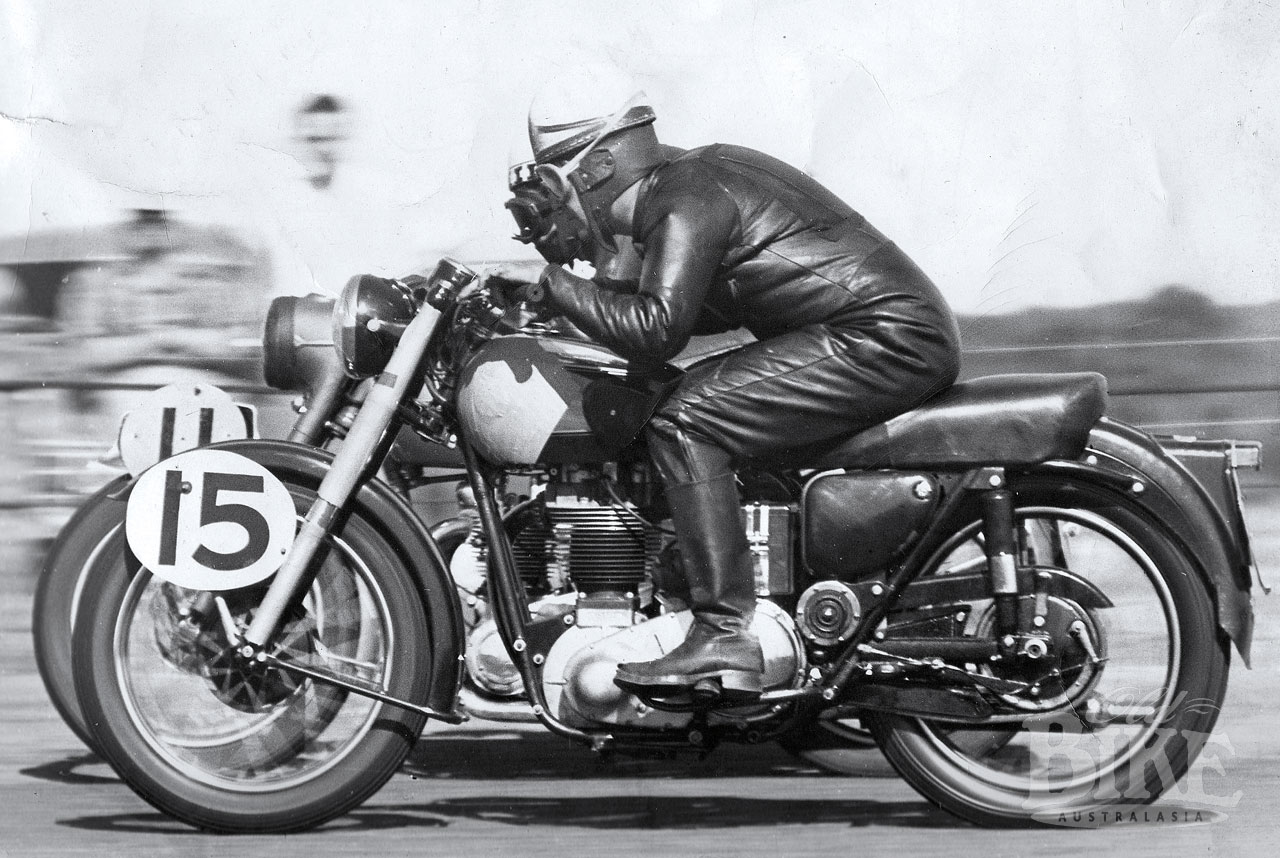

For the first few hours, the outright lead was disputed by the 500cc Triumph of Joe Bratby, Jack Godfrey’s 500 Matchless Super Clubman twin, and the 500 Tiger 100 Triumph from the Canberra team of brothers Bob and Barry Sluce, and Bryan Woodyatt. The Hinton Norton challenge had evaporated when Eric crashed at the six hour mark and received a fractured arm. In the smaller classes, Norm Osborne’s NSU led the way, while future world champion Tom Phillis, partnered by Roy East, was putting in a remarkable ride aboard the split-single 250cc Puch. The Bratby/Ron Williams/Keith Jones Tiger 100 continued to draw away from the field as the half-way point neared, holding an incredible 17 laps advantage over the Conley G9 Matchless team.

Underdogs triumph

At the 14 hour mark, terminal engine troubles halted the hard-ridden Bratby Triumph, which at that point had a lead of seven laps. This left the two Matchless teams ahead, but they were being pressed hard by the Sluce/Woodyatt Triumph. Bryan Woodyatt recalls what happened next.

“I was chasing Barry Hodgkinson’s Tiger 110 on the lower part of the circuit, and as we came onto the airfield section we both came up to lap another Triumph. Barry went one side, scattering the rubber trackside markers all over the place as he cut inside, and I went the other. Just as I was about level with this other Triumph, it shed the left hand muffler, which went straight under my front wheel, bursting the tyre. I was doing about 95 mph at the time and was thrown down the road, breaking my wrist. As I picked myself up a trackside marshal on an ex-army BSA came racing up, so I jumped on the pillion and got a lift back to the pits. While I was patched up in the ambulance Bob and Barry went to retrieve the bike. A friend of ours had loaned us an identical Tiger 100 to use for parts should we need them, so they pulled off the front wheel, petrol tank and a few other bits and headed off down the bottom of the circuit to rebuild the bike.”

While the Sluce machine was being retrieved, an even worse accident occurred. Don Blackburn (who was comfortably leading the Junior class on his Velocette) crashed at high speed on the downhill section and was struck by several other bikes, receiving fatal injuries. Wrecked machinery littered the track and the race was stopped. After a meeting between officials and riders, it was agreed to allow the event to proceed. To further add to the confusion, the lighting in the pit area, what there was of it, failed for almost four hours, and in the darkness a pressure lamp exploded and set fire to the building containing the fuel stores. The one-hour delay in racing however, allowed the Sluce team precious time to rebuild the Tiger 100, and when the event was restarted they were ready for battle again. Woodyatt, with his broken wrist and dislocated thumb heavily strapped, was pressed into duty again and went out for a two-hour stint! Bob Sluce, who was not a recognised road racer, then took over for a marathon stint, carving chunks out of the leaders’ advantage to take over the front running in the 19th hour.

They held the position to the finish, beating home the distributor-entered Godfrey/Astley/Harmon Matchless by just one lap. The Matchless squad had their strong chance of victory ruined when the bike fell over in the pits while it was being refuelled at the 20-hour mark, smashing the headlight (fortunately the race now being in Sunday’s daylight) and trapping rider Astley’s hand, which forced him to retire from any further riding. The winning total was 599 laps, 49 fewer than the previous year, although nearly one hour’s racing had been lost. The winning Triumph, owned by Bob Sluce, had just 700 road miles on the clock when the race started. The team had no trade support, unlike the fancied 650 Tiger 110 owned by importers Hazell & Moore and ridden by crack racers Keith Bryen and Barry Hodgkinson, which finished outright third on 597 laps. The Junior class was taken out by the 350cc BSA ridden by Gordon Hunt, Vince Tierney and Bob Short on 571 laps. NSUs finished 1-2 in the Lightweight class, with Kel Carruthers, Max Shearer and L, Green clocking up 567 laps, 39 more than the Victorian squad of Norm Osborne, Doug Russell and Ned Caddy. A 197cc Francis-Barnett ridden by Blair Harley, Todd Hamilton and Bernie Sinclair was the Ultra Lightweight winner on 468 laps.

In the aftermath to the event, tales of brilliance, heroism and incredible stamina emerged. The pits were a hive of industry, with wheel changes achieved in less than two minutes, gearboxes rebuilt in 40 minutes, and spectator machines cannibalised to supply spare parts. Although the four-stroke NSUs took first and second in the 250 class, the performance of the 250 Puch, which had had its entire electrical system wiped out in the crash in which Blackburn lost his life, was truly remarkable. The bike lost almost six hours while the electrics were rebuilt, and crashed again when Roy East was brought down, yet still finished fourth in its class.

Dramatic the event may have been, but for the promoters it was a financial disaster. There had been expectations of a good crowd to watch the Sunday’s action unfold, but after the tragic midnight melee, radio stations and Sunday newspapers announced that the event had been cancelled, leaving spectator areas bare as the race drew to it conclusion.

And so the “World’s Longest Road Race” slipped into history. However the concept of long-distance racing for standard production machines retained strong support among the Australian sporting fraternity. 14 years later endurance racing finally returned in the form of the Castrol Six Hour Race at Amaroo Park. “The Six Hour” went on to become the blue ribbon title on the Australian calendar, but it owed much to the pioneering efforts of the brave riders who swept around an unlit cow paddock all those years previously.

1954 Results

Outright winner: BMW R68 600cc (Jack Forrest, Don Flynn, Len Roberts) 648 laps (approx. 2332 km 1458 miles)

Unlimited/Senior Class:

1. BMW R68 600cc (Jack Forrest, Don Flynn, Len Roberts) 648 laps

2. Triumph 650cc (Keith Bryen, Barry Hodgkinson, Bill Tuckwell) 629 laps

3. Matchless G9 498cc (Keith Stewart, Keith Conley, Sid Webb) 627 laps

Junior Class:

1. AJS 350cc (J. McLeay, F. Mcleay, Max Alexander) 530 laps

2. AJS 350cc (D. Newling, C. Dingham, F. Moran) 510 laps

3. Velocette 350cc (Ray Smith, Basil Hazelhurst, B. Beere) 504 laps

Combined Class:

1. BMW R25 250cc (Don Bain, Wal Hawtrey, Jack Humphries) 547 laps

2. Puch 250cc (B. Watson, F. Dolson, E. Berry) 407 laps

Sidecar:

1. Norton 500cc (Bruce Rands, R. Rottenbury, Alf Higgins) 461 laps

2. BSA 500cc (John Kestrel, Eric Moore, Hilton Murray) 44o laps

3. Triumph 650 (John Moss, Dick Mason, Jim Burgess) 438 laps

1955 Results

Outright winner: Triumph 500cc (Barry Sluce, Bruce Woodyatt, Don Sluce) 599 laps (approx. 2157 km 1348 miles).

Unlimited Class:

1. Triumph 649cc (Barry Hodgkinson, Keith Bryen, Bill Tuckwell) 591 laps.

2. Triumph 650cc (K. McCallum, W. O’Connor, M. McKinnon) 527 laps

3. Triumph 650cc (Frank Percy, Brian Perrot, Ron Toombs) 462 laps

Senior Class:

1. Triumph 500cc (Barry Sluce, Bruce Woodyatt, Don Sluce) 599 laps

2. Matchless 498cc (Jack Godfrey, John Astley, Gordon Harmon) 598 laps

3. Matchless 498cc (Keith Conley, Noel Hoare, Peter Hurley) 586 laps

Junior Class:

1. BSA Gold Star 350cc (Gordon Hunt, Vince Tierney, Bernie Short) 571 laps

2. Royal Enfield 348cc (K. Goner, K. Tride, K. Sinclair) 497 laps

3. BSA 350cc (Don Flint, Vic Nicolson, I. Richards) 473 laps

Lightweight Class:

1. >NSU 247cc (L. Green, M. Shearer, Kel Carruthers) 567 laps

2. NSU 247cc (Norm Osborne, Doug Russell, G. Caddy) 528 laps

3. Francis-Barnett 197cc (Todd Hamilton, Blair Harley, Bernie Sinclair) 474 laps.

Ultra Lightweight Class (to 200cc)

1. Francis-Barnett 197cc (Todd Hamilton, Blair Harley, Bernie Sinclair) 468 laps.

2. CZ 150cc (K. Kirkness, J. Gammon, G. Adams) 424 laps

3. CZ 150cc (T. Cave, R. Elsley, B. King) 416 laps.