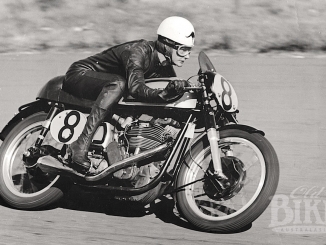

Like many aspiring racers, the war robbed Laurie Boulter of perhaps his best years. But despite being on the wrong side of thirty, the South Australian resumed his career after the war and had a solid claim as Australia’s best road racer after Harry Hinton.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Byron Gunther, Ray Knight, Graham Boulter.

He had never travelled further than Bathurst in New South Wales, a major drive from his home town of Adelaide, when he decided to contest the Isle of Man TT in 1953. Travelling alone as a private entrant he finished a remarkable 11th in the Senior TT, and returned the following year to improve on this performance. But even before official practice started for the 1954 TT Laurie was dead, and almost half a century passed before the shocking truth behind his death was revealed.

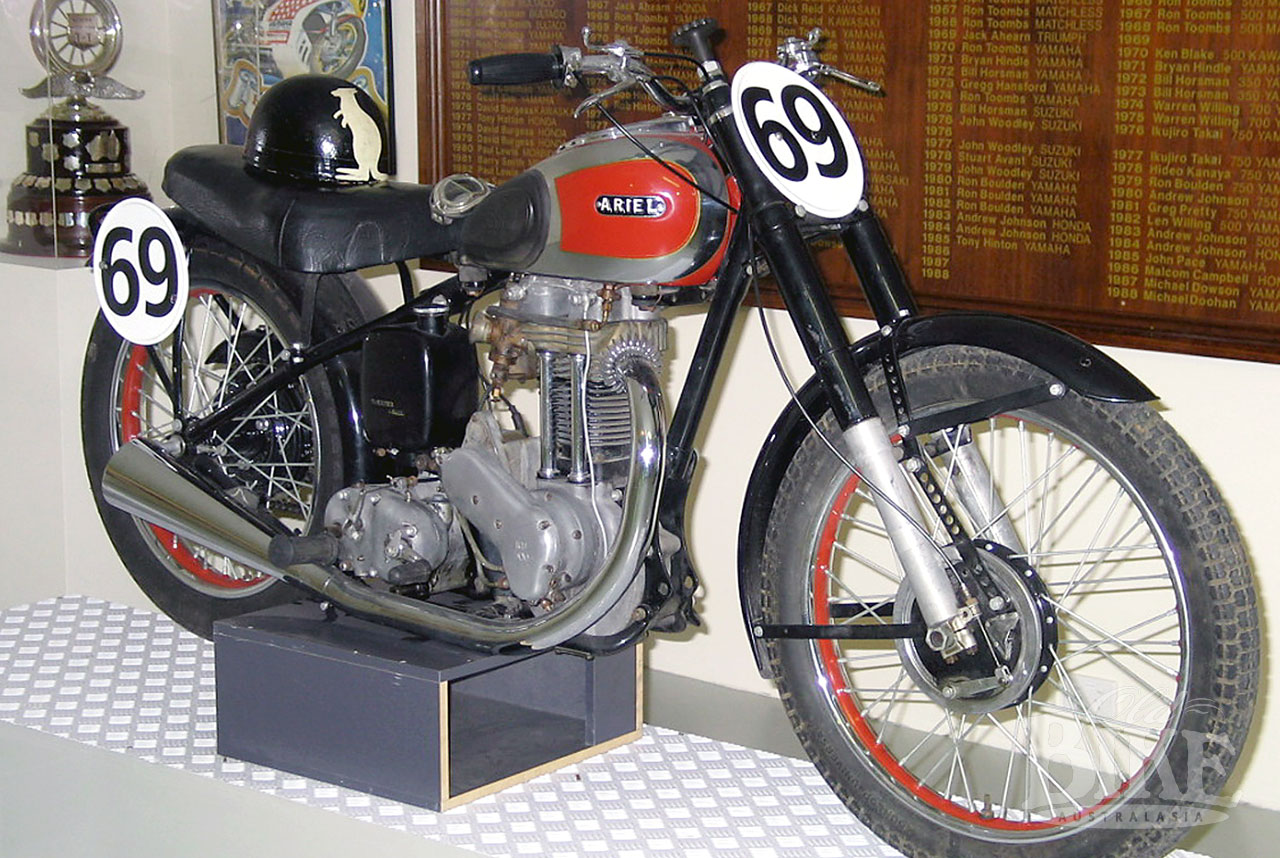

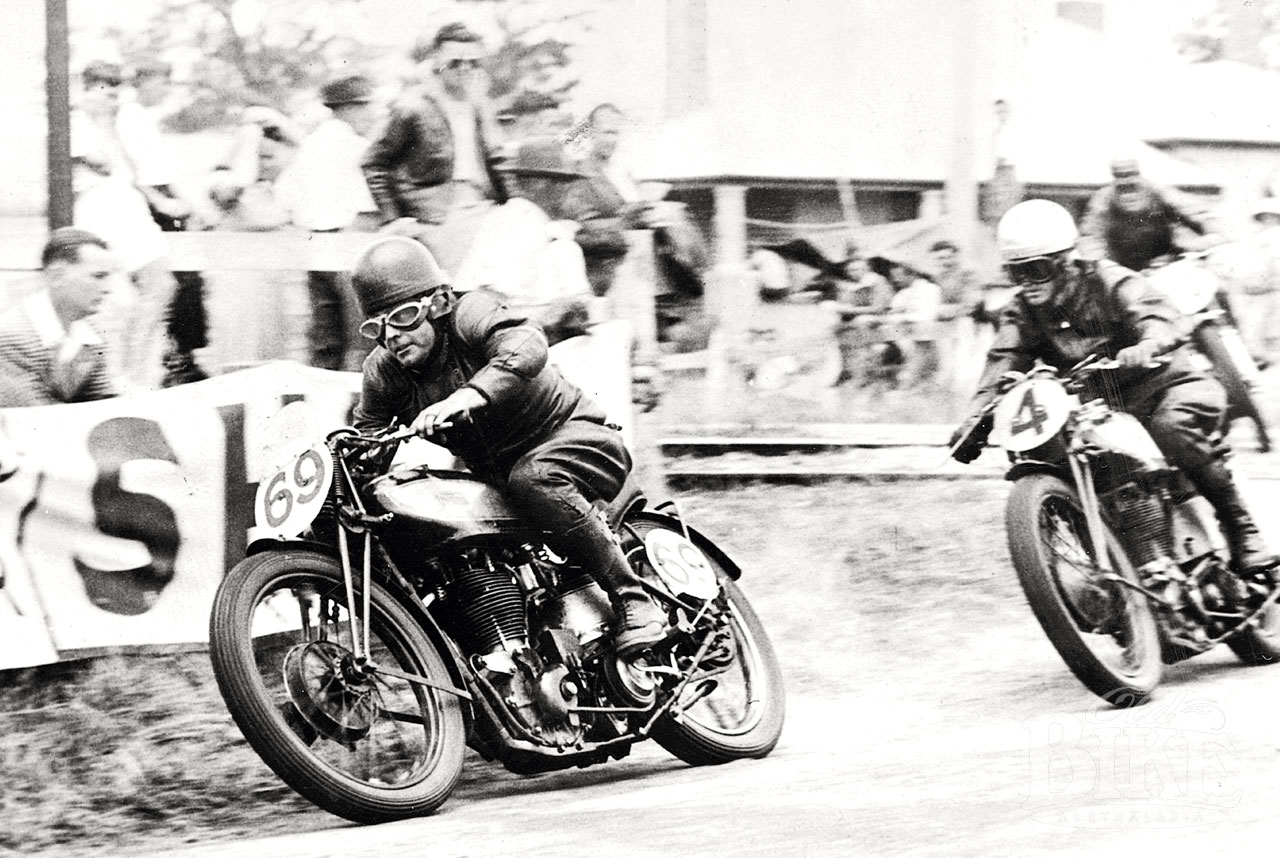

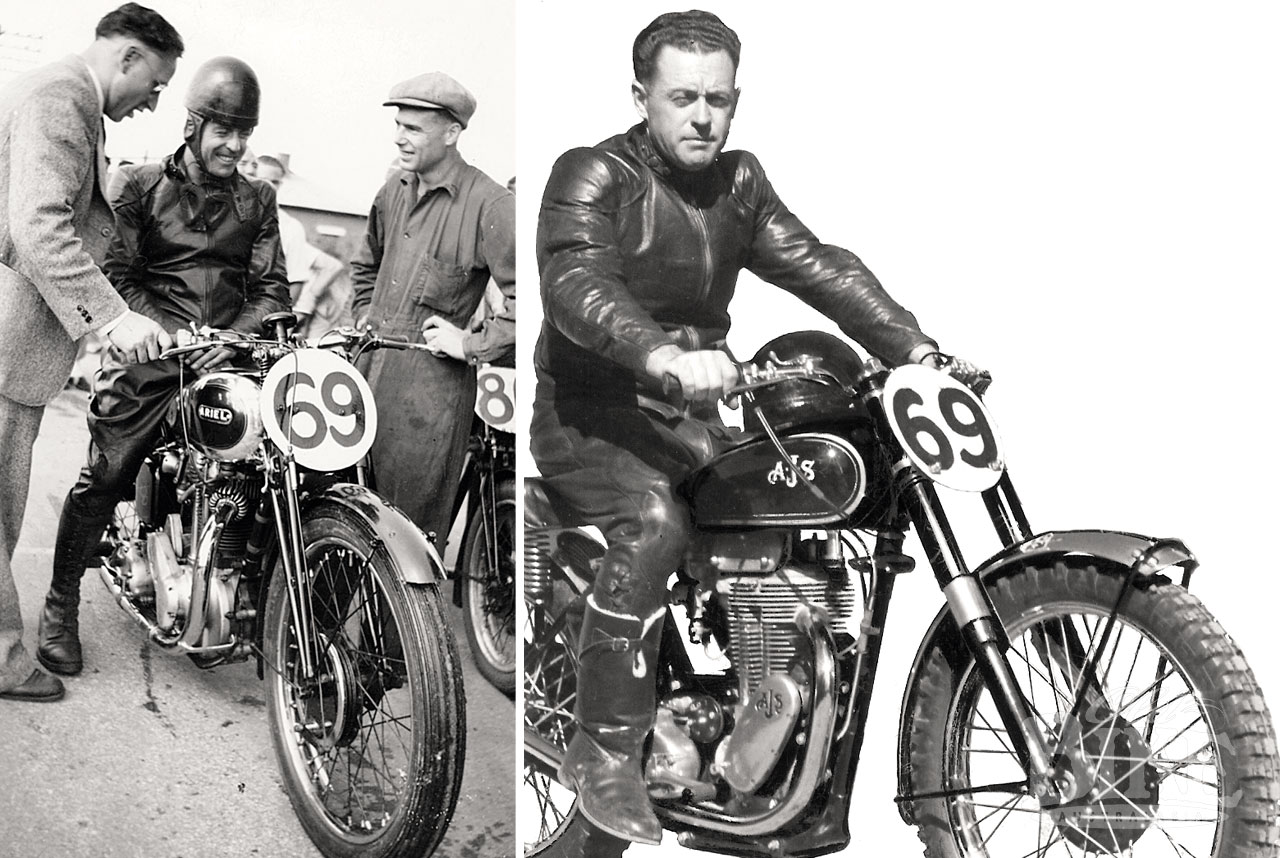

Laurie Boulter’s motorcycling career started by accident – not his, but his father John’s. Boulter Senior, a horse trainer in Adelaide, bought a motorcycle for £2/10/- to ride to work, but found almost immediately that the machine did not respond to commands like a horse did. After extracting himself from a paling fence, he gave the bike to young Laurie. The year was 1935, and it took the then 23-year-old little time to become a keen and accomplished rider. In Adelaide, scrambling and sand racing on the nearby Sellick’s Beach were the way to go, and Laurie assembled a hybrid device powered by a Rudge engine on which he competed with considerable success. Just when he was making his name as a true all-rounder (he rode in scrambles, hillclimbs, road racing, Miniature TT dirt tracks and at Camden Motordrome Speedway) along came the war. By 1946 Laurie had opened his own motorcycle business in the Adelaide suburb of Torrensville and had switched to road racing with a 500 Ariel and his 500 Rudge. He quickly established himself as South Australia’s leading rider, and soon the racing tackle was upgraded with a 350 KTT Velocette and a 596cc OHC Norton.

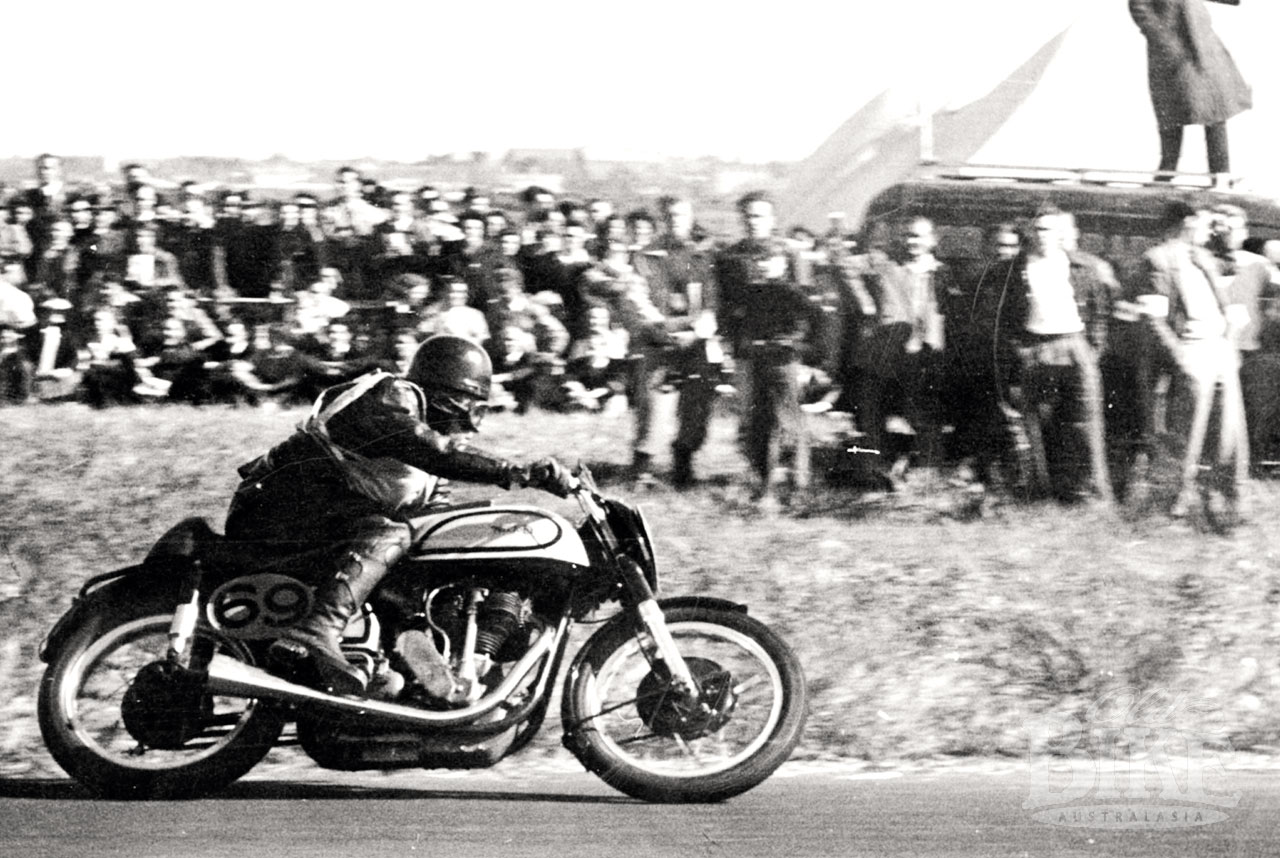

In his home state Laurie was well nigh unbeatable, but he also ventured to Victoria when time permitted, collecting wins at Fishermens’s Bend and Ballarat against the cream of the country’s tar men. His big break came when he took delivery of a new 500 ‘Featherbed’ Manx Norton in January 1952, and at Bathurst a couple of months later, finished a brilliant second to Harry Hinton in the Australian Senior Grand Prix.

To sail or not?

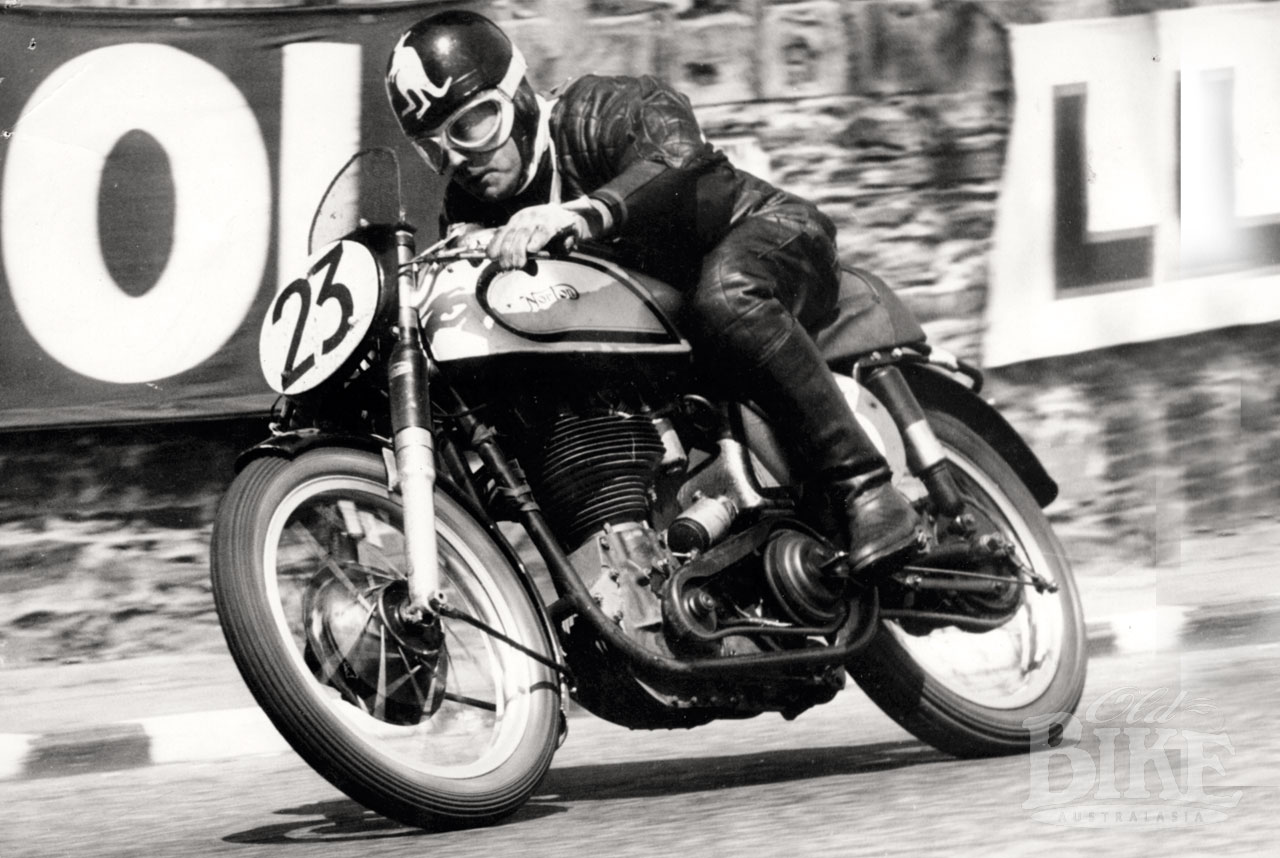

Naturally Laurie had dreamed of racing overseas, but devotion to his business and young family had always ruled out the expensive and time consuming pilgrimage to Europe. But with the success of the new Norton, and a little prompting from Ken Kavanagh, he decided to take the plunge in 1953. Taking his 500 Norton with him, Laurie purchased a 350 in England and headed for the Isle of Man. He rode as a self-funded private entrant, outside the official Australian team, and began well with 26th place at 81.10 mph in the 350cc Junior TT. But better was to come. In the Senior TT, Laurie powered to a brilliant 11th place, at 85.52 mph – one the best-ever performances by a TT newcomer. Six months after he left, he was back in his shop in Adelaide, and professed to have no further plans, despite his sensational performance, to race overseas. But two factors changed his decision. The first was a great win in the Victorian Unlimited GP at Ballarat on New Year’s Day, 1954, and the second was his successful nomination, along with Maurie Quincey and Jack Ahearn, to officially represent the Commonwealth of Australia at the 1954 Isle of Man TT. The nomination brought with it a modest financial bonus, and the friends he had made at Norton Motors the previous year ensured that he would be able to obtain the latest production equipment. It was too good a chance to pass up.

Back on the Island

It was Thursday afternoon, the day before the start of official TT practicing, when Ken Kavanagh stepped off the boat at Douglas. After defecting from the Norton works team at the end of the 1953 season, Kavanagh was now a member of the illustrious Moto Guzzi squad. After checking into the Majestic Hotel at Onchan, Ken wasted no time in hiring a car and setting off around the course on a re-familiarisation tour. His first stop was Handley’s Corner, which had been widened considerably since the 1953 TT and was now a good gear higher than previously. Ken parked his Austin A40 at the entrance to a farm about 200 yards after the left-right ess-bend, and walked back to study the racing line and determine a new “peel off” point. As he strolled along, deep in thought, a Riley saloon passed, the driver giving a wave as he spotted Kavanagh, before disappearing around the bend. The vehicle was driven by a Doctor Letchworth – a retired physician who enjoyed an annual role as an official ACU doctor at the TT. Almost simultaneously, Ken picked up the sound of a motorcycle arriving from the direction of the Eleventh Milestone.

“I knew it was a racing machine…I guessed right; a 500 Manx with a baffle fitted over the end of the megga. When it was abreast of me I looked and there was Laurie Boulter, one of my oldest rivals. He was going about forty miles per hour, and like me, was checking the circuit. He had a peaked cap on backwards, a pair of goggles, and was waving at he with his right arm…yelling the usual friendly insults at me…”Hi, ya idiot bastard, still walking?” I knew that once through Handley’s he would have stopped, walked back and we would have chatted about all sorts of things for half an hour…but it never worked out that way.”

“He (Laurie) was well in against the left bank and only had his left hand on the bars. I was on the right side footpath and could see through the bend. There was the Riley coming back through the bend in reverse! Laurie was waving…I was literally screaming at him to look ahead…he was still laughing at me as he bent it into the left hander with only his left hand still on the bars and right hand high in the air. He saw the Riley when it was only maybe ten yards ahead, but had only time to pick up the Manx and clap on the rear brake. The rear wheel broke away to the left and the Manx slapped sideways into the boot of the Riley. Laurie flew over the top of the car and slapped with a terrible force with the flat of his back against the high stone wall that had been built on the right side of the road… maybe ten feet in the air. He fell like a sack of potatoes and never moved again.”

Doctor Letchworth and his wife were quickly out of the car as Kavanagh, horrified, walked slowly to where Boulter lay. The doctor announced that Laurie was still breathing, and some cushions and a plaid rug were removed from the Riley to form a makeshift bed. Doubling up to the farmhouse where he had parked his car, Kavanagh called the police and an ambulance, but it was all too late to help Laurie Boulter, who died minutes later.

Back in Douglas, Kavanagh went to the boarding house at which Boulter had been sharing a room with Victorian rider Gordon Laing. “I was in a daze. It just didn’t seem real what had happened in the past two hours. Gordon Laing, Ray Amm, myself and Laurie had become very close friends in 1953 at (the Norton factory) Birmingham. Of the non-works riders, Gordon and Laurie were the only people who had free access to the Norton Racing Department.” After unfolding the sorry tale to Gordon, he went next to the police station. In these intervening few moments before he entered the station, Kavanagh decided to “lie a little in my statement”.

“Laurie was dead…nothing more could hurt him…and the thought of poor old Doc whatever-his-name-was getting nailed for manslaughter was too much for me. I only ever told the truth to Gordon Laing…I hope that Mrs Boulter will forgive me.”

In a sworn statement at Peel Court on June 2nd, 1954, Kavanagh testified that Doctor Letchworth had ‘stopped’ his car, which had then been struck by Boulter, whose attention had been diverted upon seeing him (Kavanagh) walking along the footpath. At the inquest, the police called an “expert” – a member of the Manx Transport Board. They showed him the rear swinging arm and rear wheel from the Manx, which had broken away from the frame in the crash. In his “expert” opinion the Norton had not been assembled correctly, so perhaps had helped cause the accident. The judge was most impressed when the ‘expert’ pointed out that the wheel nuts had not damaged the paint on the swinging arm, and explained that this meant the nuts had never been properly tightened.

A verdict of misadventure was returned. In Kavanagh’s opinion, “As the doctor, Laurie and myself were all foreigners over from England, with no IOM residents involved, the police and judge asked as few questions as possible… they were just happy to get us out of the place.”

Gordon Laing agreed to write to the Boulter family, but within a month, he too was dead. Gordon had been drafted into the Norton team for the Ulster Grand Prix, and retained for the following week’s Belgian GP. On the second lap of the 350 race, Laing left the road at top speed and was killed instantly.

The following year, 1955, Kavanagh was back in the Island (where he scored the first-ever win by an Australian, in the Junior TT), and was approached by a solicitor who requested that Ken again describe the circumstances of the accident. The solicitor claimed to have independent witnesses who had seen the incident and had stated that the Riley car was reversing through the bend in the middle of the road. Kavanagh refused to make a direct statement, saying only that his sworn testament was on record with the IOM authorities. Nothing more came of it.

Years later, Kavanagh disclosed to Boulter’s family that the ‘expert’ opinion offered in court was ‘bloody silly’. He also revealed that in the time taken for him to sprint to the farmhouse to summon help, the Riley had been moved from the point of impact, ostensibly to allow a bus to pass.

Nothing would have saved Laurie Boulter’s life. It was one of those tragic cases of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. But the handling of the aftermath to the accident certainly left Ken Kavanagh with a load on his conscience for almost half a century.

Compiled with the cooperation and permission of the Boulter family.