Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

As a relative newcomer to volume motorcycle production, Kawasaki wasted little time in establishing itself as perhaps the most innovative member of what was then the Japanese invasion of the lucrative US market in the ‘sixties. Although it had entered the field via the expedient of purchasing the long-established Meguro firm, and indeed simply re-badged some of Meguro’s existing four strokes, Kawasaki then turned its attention to a range of well engineered two strokes, most featuring the then revolutionary rotary disc valve induction.

The range of Kawasaki ultra lightweights performed well enough to make the establishment sit up and take notice, but what really set tongues wagging was the sensational 250cc A1 “Samurai’ of 1966. The 250 just pipped the Bridgestone 350 GTR to become the first Japanese production twin to be fitted with twin rotary disc valves, and to press home its case, Kawasaki also produced the A1R production racer. The A1R was meant to be a serious challenger to the Yamaha TD1B, which it was, but when Yamaha produced the TD1C it was a quantum leap and the A1R was left far behind. However the road going A1 sold well, particularly in the US, and following Bridgestone’s lead, Kawasaki decided to make another bold move and enter the over 250cc segment which was still dominated by non-Japanese brands.

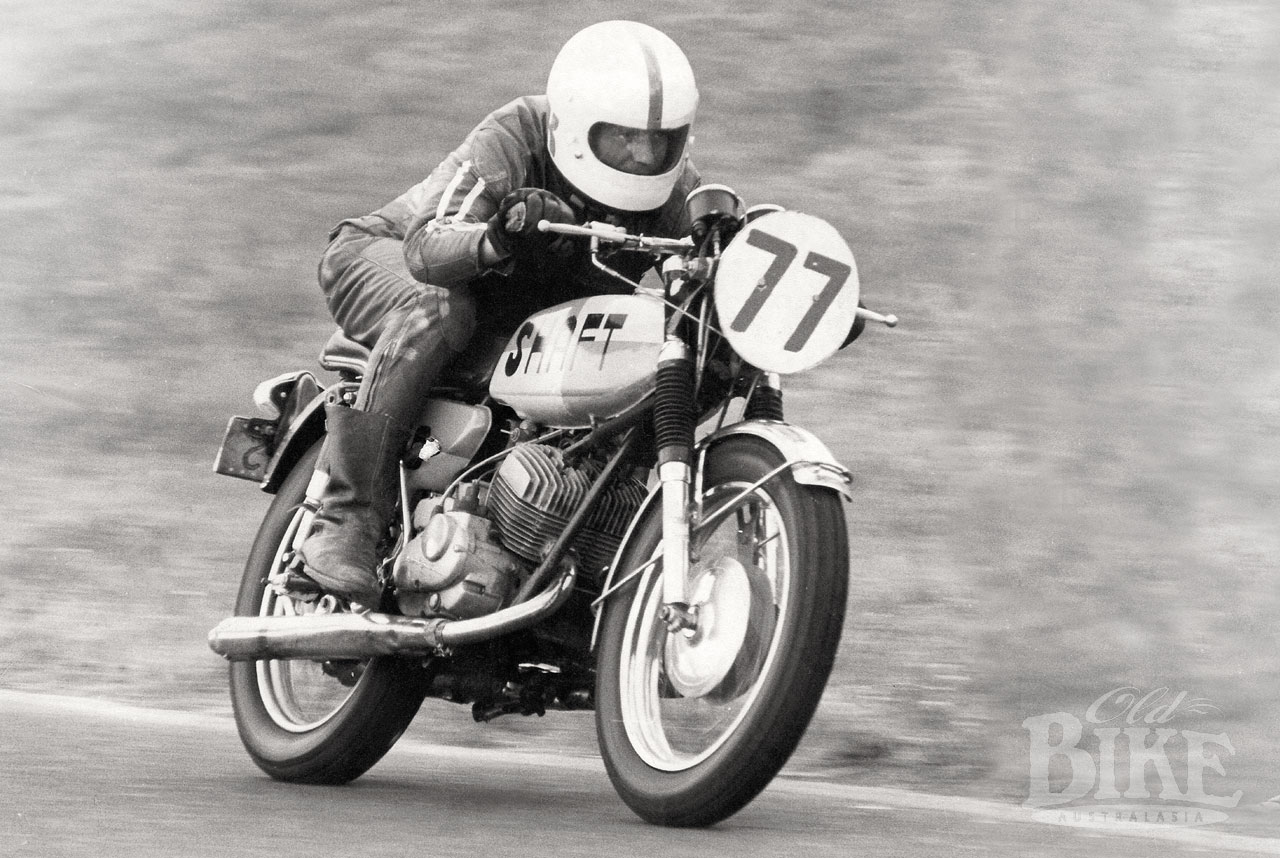

That machine was designated the A7, also known as the Avenger, a title deemed necessary to capture the imagination of the American buying public. And once again, Kawasaki produced a road racing version, albeit in very limited numbers; the A7R. A handful of these came to Australia, the most successful being those tuned by Ron Angel and ridden by Victorian Dick Reid, who won the 1968 Australian 350cc Grand Prix at Bathurst.

The Avenger was to all intents and purposes, a bigger-bore version of the Samurai, however it was a case of ‘back to the future’ for the Big K. The samurai design actually started life (at least on the drawing board) as a 350, before the marketing department strongly urged the engineers to first conquer the quarter-litre category. So the 250 emerged in ‘long stroke’ 53mm bore and 56mm stroke dimensions, and was well received, and once it had established a foothold, it was a relatively simple task to produce the 350, which was actually a 338. This was achieved by increasing the bore size to 62mm, a nicely over-square engine with an appetite for revs. As well as more outright power, there was a corresponding increase in torque, and to cope with the extra mid-range grunt, Kawasaki fitted the A7 with a beefed up clutch.

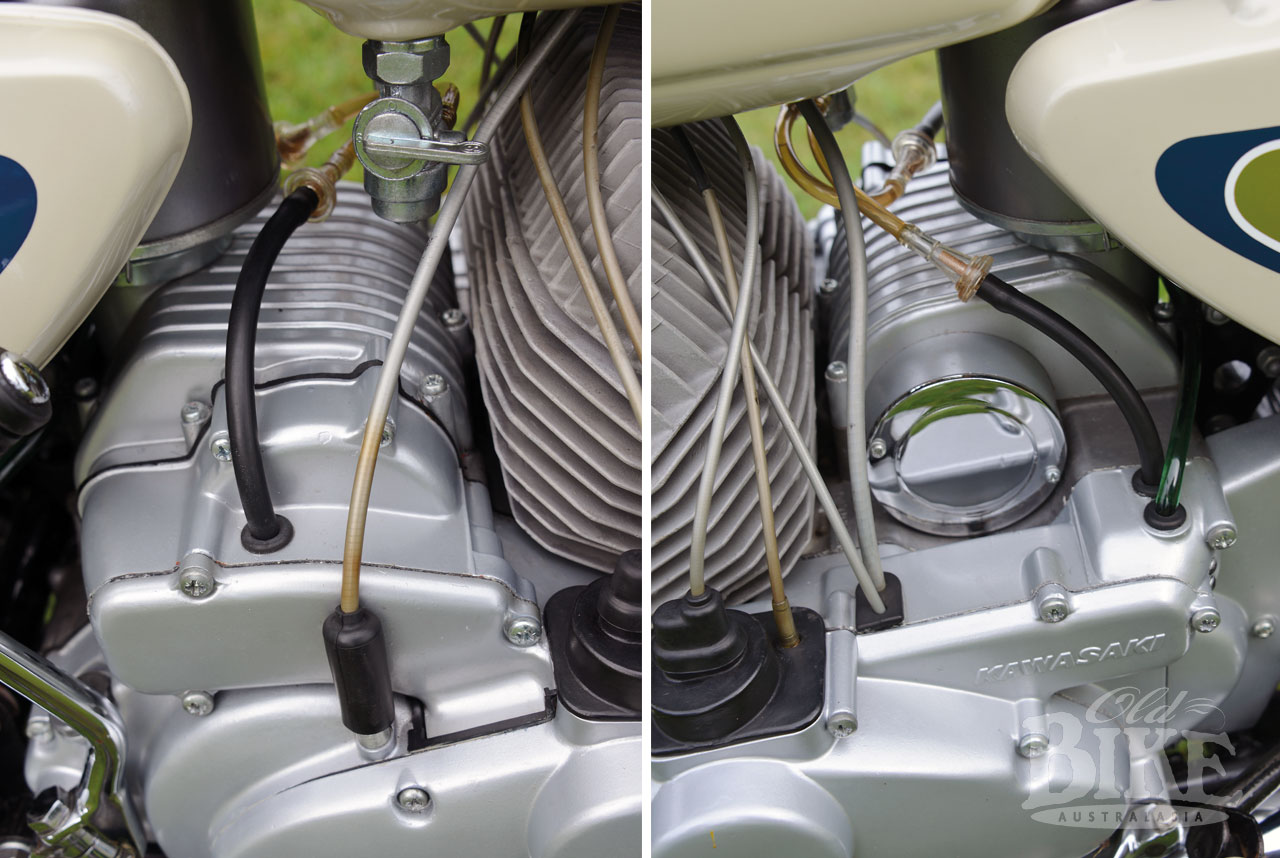

Poking out at either end of the crankshaft was a Mikuni VM 26mm carburettor, each concealed in a neat cast-alloy case that led back to a large capacity paper air filter which sat across the top of the crankcases – where the carburettors on a normal piston-port engine would be. Inside these cases sat more original thinking, for the electrics also lived in here, with a constant flow of cooling air running over the alternator. The usual ‘roar’ from a multi-cylinder two stroke was nicely muted on the A7. A gear-driven generator, running at half engine speed, produced the current for the twin sets of points which were mounted on a plate on the end of the generator, running at 23º advance. This was deemed to be a superior arrangement to the method of mounting the points on the end of the crankshaft where flexing and fluctuations in timing can occur. The drawback of the design is the inherent width of the complete engine, which is more a problem on a racer than on a road machine. Later disc valve designs, such as can Am, moved the carburettors from the end of the crankshaft to behind the engine, with a tract back down to the disc valve to feed in the mixture. It was this excessive width that forced Kawasaki to abandon their disc valve design when producing the H1 and the subsequent range of triples, as the task of feeding the centre cylinder via a disc valve while containing the width would have proved insurmountable.

In one respect – that of lubrication – the 350 engine differed from the 250. On the 250, oil was mixed with straight petrol by injecting it into the inlet port, where the action of the crankshaft effectively mixed the oil and fuel and distributed it to the bottom end bearings and the walls of the cylinders. On the 350, the same mixture process was supplemented with direct oil injection to the outer crankshaft main bearings (the two inner bearings retained oil mist lubrication) and the big ends of the connecting rods. This system had been pioneered on the racing A1R, and was given the marketing title of Kawasaki Injectolube.

Early road tests of the A7 invariably compared it with the 250, and while the performance of the 350 was universally applauded, ‘Vibration” was a word that cropped up often. For this reason, the handlebars are rubber mounted, although the engine is not. Excessive fuel consumption was another gripe, although it was noted that the Avenger seemed happy on the standard grade of petrol available at the time. Perhaps it was the stronger springs fitted in an effort to tame the torque, but the clutch also quickly gained a reputation for dragging, making finding neutral when stopped a tricky proposition. The five-speed gearbox had neutral at the bottom of the range, rather than between first and second.

In terms of comfort, the A7 gained full marks, with its large, plush seat and high, wide handlebars. Brakes – 180mm front and rear – were also highly praised, although the suspension was on the stiff side, perhaps a throwback from the racing models. That torquey engine also drew much admiration. Although the main power band extended from 6,000 rpm to 9,200, the engine would pull cleanly from as low as 2,000 rpm. Although maximum power was listed at 7,500 rpm, the engine could be buzzed well past this, resulting in some testers achieving as high as 107 mph (173 km/h) at 9,200 rpm, but a happy highway rate of 75 mph meant the engine was just loafing along in the lower end of its rev range. Acceleration was where the A7 really drew rave reviews, turning 14.4 seconds for the standing quarter mile with a terminal speed of 94 mph – the domain of 500s and even bigger stuff.

A year after the release of the A7 came the A7SS – a Street Scrambler in the style much favoured by the American market. It was no coincidence that the Honda CL77 (street scrambler) was at the time the biggest selling motorcycle in USA, and it was priced almost $200 less than the US$845 A7SS. In reality, there were few changes on the SS apart from the high level exhaust system which ran on the left side and was fitted with a perforated heat shield.

In 1969 the battery/coil/points ignition system gave way to a Capacitor Discharge (CDI) system which included a system that increased voltage to reduce unburned fuel. Kawasaki worked quickly to implement the CDI system and refine it, knowing that stringent US regulations concerning exhaust emissions were just around the corner. Those regulations ultimately killed off not only the small Kawasaki twins, but road-going two strokes in general.

Show and go

David Howe’s 1971 A7 is a rare example, being the final incarnation of the twin before it surrendered to the avalanche of larger models that swept the market in the ‘seventies decade. In fact, the 350cc market, at least in USA, was a shadow of its former self – in six years of production, the Honda CB/CL/SL 350 accounted for 626,000 sales in the US alone.

The pearly-white colour scheme on David’s A7 gives it a highly distinctive appearance, and there are other subtle differences from the earlier models. “For some reason Kawasaki changed the fuel tank just for the 1971 models,” David says. “The previous year the A7 was available in red, blue and yellow, and the tank had a recess on the top, the same as the H1 triple. On the 1971 model it is flat. This must be the only bike made with two steering dampers – it has the normal friction damper in the steering head, plus the telescopic damper on the right side; I can’t see that it needs two. They also fitted 28mm carbs, with slightly bigger transfer ports, and this must account for why it is so thirsty. I have to make sure there’s plenty of fuel stops on the route whenever I ride it, especially if we’re two-up.

“They also changed the front mudguard for 1971, with the struts kicked up, whereas the earlier ones were straight. At this time, all the US models had CDI, whereas the British bikes had points. We (in Australia) seemed to get whatever was left, so we had a mixture of CDI and points models – this one has points. The earlier models had chrome mudguards with rear quite deeply valanced, but the guards on mine are stainless.”

At the recent Vintage Japanese Rally in Canberra, David and wife Colleen were presented with the President’s Choice Award for the A7, but this motorcycle is no mere show pony. It’s a regular ride in many rallies, including the week-long Bathurst Easter Tour, plus of course the mid-year Macquarie Towns Rally; David being former president of this very active club. Perhaps the little twin may see less action in the immediate future, because David is putting the finishing touches to a Suzuki GT750M, and there’s a nearly-finished Bridgestone 350GTO waiting in the wings as well.

Croz capers: Kiwi TT-winner Graeme Crosby has fond memories of his Kawasaki A7 Avenger (and a 44-gallon drum)

“It was my first real production racer. I bought it from my mentor Eric Bone at a bargain price of NZ$650 in 1972. It was a quick and nice handling road bike with good ground clearance and a special engine noise that only disc-valved engines made. Although older and perhaps not as refined as the more modern RD350s, I didn’t have to worry about the carburetor slides jamming wide open or being thrown off because the foot pegs touched and dug in.

In one of my first races on the A7 I rode to a brilliant 2nd place behind Dale Wylie and was followed home by a 44 gallon drum in 3rd place! The drum followed me over the line as a result of me running off the track. When I got back on the track I got tangled up with the 44 gallon drum and the rope that was supposed to hold the crowd back.”

Specifications: 1967 Kawasaki A7 Avenger

Engine: Twin cylinder, rotary disc valve two stroke.

Bore x stroke: 62mm x 56mm

Power: 40.5bhp @ 7,500rpm

Carburation: 2 x 26mm Mikuni VM

Ignition: Battery and coil

Gearbox: 5 speed, wet clutch.

Primary drive: Helical gear

Final drive: Chain with cush drive in rear hub.

Lighting: 12 volt 6AH.

Suspension: Telescopic front forks, swinging arm rear.

Tyres: Front: 3.25 x 18 Rear: 3.50 x 18

Wheelbase: 1295mm

Seat height: 807mm

Weight (wet): 148kg