Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Dennis Quinlan and Jim Scaysbrook

Magazine owner, prolific motorcycle and automotive book publisher, entrepreneur, ex-racer, ex-motorcycle dealer; Floyd Clymer was never afraid of a challenge. He even wrote a book instructing the reader in the art of cutting one’s own hair.

Born in Indianapolis in 1895, Clymer showed such a flair for business that his father set him up in a former dentists office where he became known as “the Kid Agent”, selling cars from the age of 11. By 13 he had secured a Ford dealership. By age 16 he was racing motorcycles and made history in 1916 by winning the first-ever Pike’s Peak Hill Climb riding an Excelsior. The celebrity status that accompanied that victory led him to become a member of the illustrious Harley-Davidson factory team, adding that brand to his chain of motorcycle dealerships which already sold Excelsior, Indian and Henderson.

Even a stint in prison failed to halt the growth of his empire. Controversially charged with fraud, Clymer spent 12 months in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was such a model prisoner that he was even permitted leave from prison to compete in local motorcycle races.

By 1930 he had moved his headquarters to Hollywood, taking over Al Crocker’s Indian Distributorship for the West Coast. Not content with a burgeoning business empire, he promoted numerous AMA national championship races and set numerous city-to-city motorcycle records.

During World War II, with motorcycle sales in the doldrums, he branched into publishing. His first venture: Floyd Clymer’s Historical Motor Scrapbook, was such an outstanding success it spring-boarded him into a constant stream of publications, including a long-running yearbook on the Indianapolis 500 which was first printed in 1946. In 1951 he purchased the fledgling Cycle magazine from Petersen Publishing, which he owned until 1966.

So when he began using the Indian name in 1963 (some sources say without actually purchasing it from the holders of the trademark), he knew he had a big job ahead of him. Indian, the brand, had been kicked from pillar to post since the last of the ‘real’ bikes slipped out of a by-then unenthusiastic market in 1953. Clymer knew that a return to a bespoke big v-twin was impractical, uneconomical, unachievable, and in the face of a market increasingly besotted with Japanese gadgetry, commercially unwise. What he envisaged was a range of motorcycles that would appeal to conventional tastes, built using existing components and embodying what he considered to be the most desirable aspects of all worlds, at least in motorcycling terms. In this respect Clymer was completely at odds with current fashion. In a motorcycling world craving rocket ship two strokes and Japanese multis, he went the retro route, possibly because he was the only one doing so, before retro became cool. Clymer’s CV already included the Munch Mammoth, so the enormity of the project weighed little upon him. What most found it hard to understand was why an extremely wealthy man in his twilight years would even bother. And the choice of a Velocette engine, when many others were to be had? Put it down to mild eccentricity.

Clymer looked not to Japan for inspiration, but to Italy, and began an association with the respected engineer Leo Tartarini, the owner of the Italjet concern. Tartarini was a tyro when it came to churning out new models, and was well tapped in to the vast Italian network of component suppliers. The plan was for an eventual Indian range stretching from mini bikes to big stuff, beginning with a 50cc Minarelli-engined mini bike that was to be called the Indian Papoose. On a more serious note, Clymer and Tartarini planned to produce a 500 single and a 750 twin, sourcing powerplants from Velocette and Royal Enfield respectively.

In the case of the 500, known as the Indian Velo, two factors combined to scuttle the project. One was the collapse of Velocette in 1970, and the other was Clymer’s sudden death from a heart attack in January of the same year. In the case of Velocette, the malaise went back well before Clymer appeared on the scene. Increasingly unable to pay the bills of component suppliers, Velocette slowly choked to death, ironically with a healthy order book. Some suppliers, such as Lucas, which was owed a considerable amount, were prepared to tough it out and extended their credit terms. Others, such as Amal, which had just 100 pounds owing, were not. All this impacted badly upon Clymer, and hence the Indian Velo project.

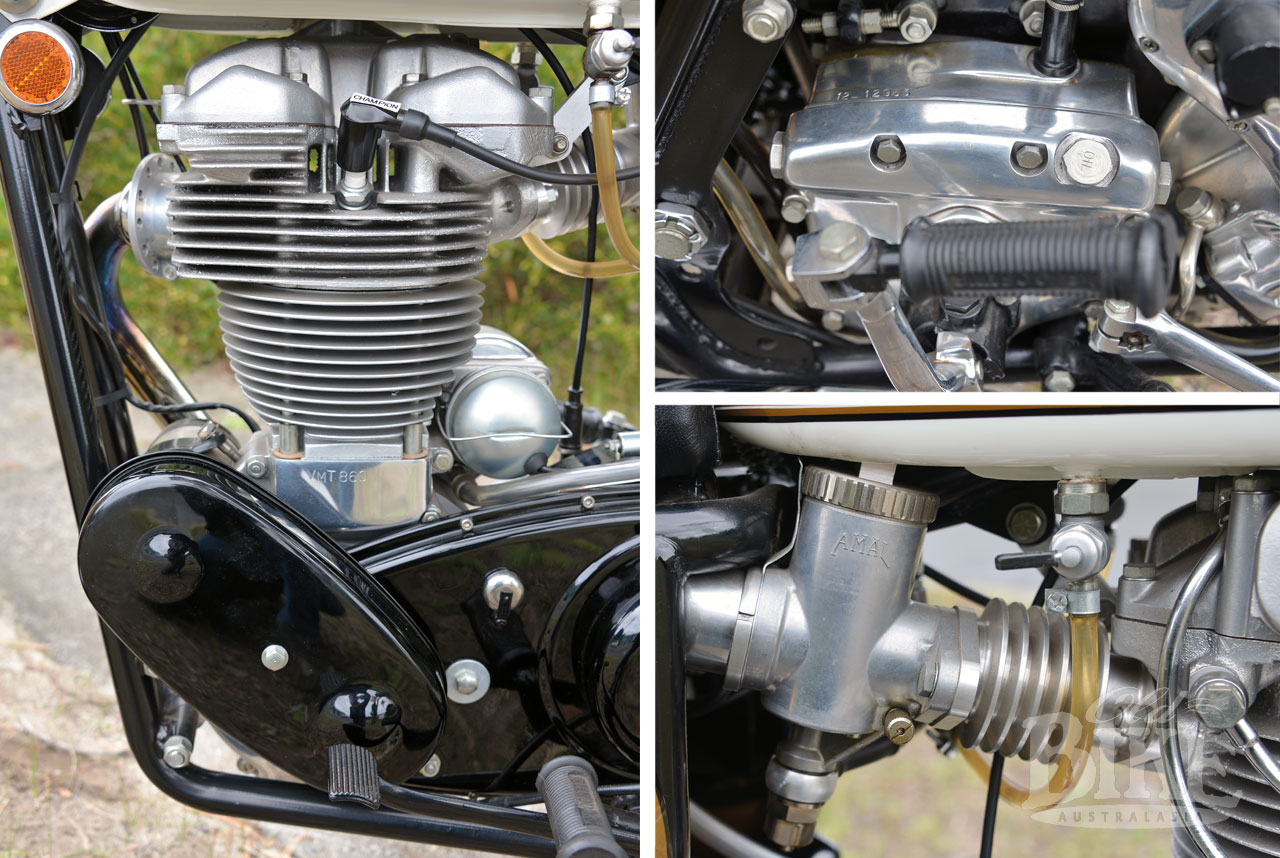

Records are sketchy, but Clymer had managed to purchase around 150 complete engine/gearbox assemblies from Velocette, the majority of which were in standard MSS/Venom specification. Less than 50 were Thruxton units, with the special cylinder heads which used modified inlet ports, reduced valve angle and a flatter combustion chamber, as well as a close-ratio gearbox with 10.0:1 first gear. One of the first traditional components to disappear was the magneto, and most of the final run of Velo engines used coil and battery – identified with the C after the engine number. Such is the case with all the Indian Velos. A 30mm Amal Concentric carburetor was used on the Venom units, but some of the Indian/Velo/Thruxtons retained the enormous 1 3/8” Amal GP. With magnetos in critically short supply, coil ignition was standard on the Indian Velo. Very few other Velocette components were used in the Indian velos, but one was the standard steel oil tank, which was hidden from view behind the right side cover. The Velocette pressed steel primary chain case and rear sprocket cover were also retained.

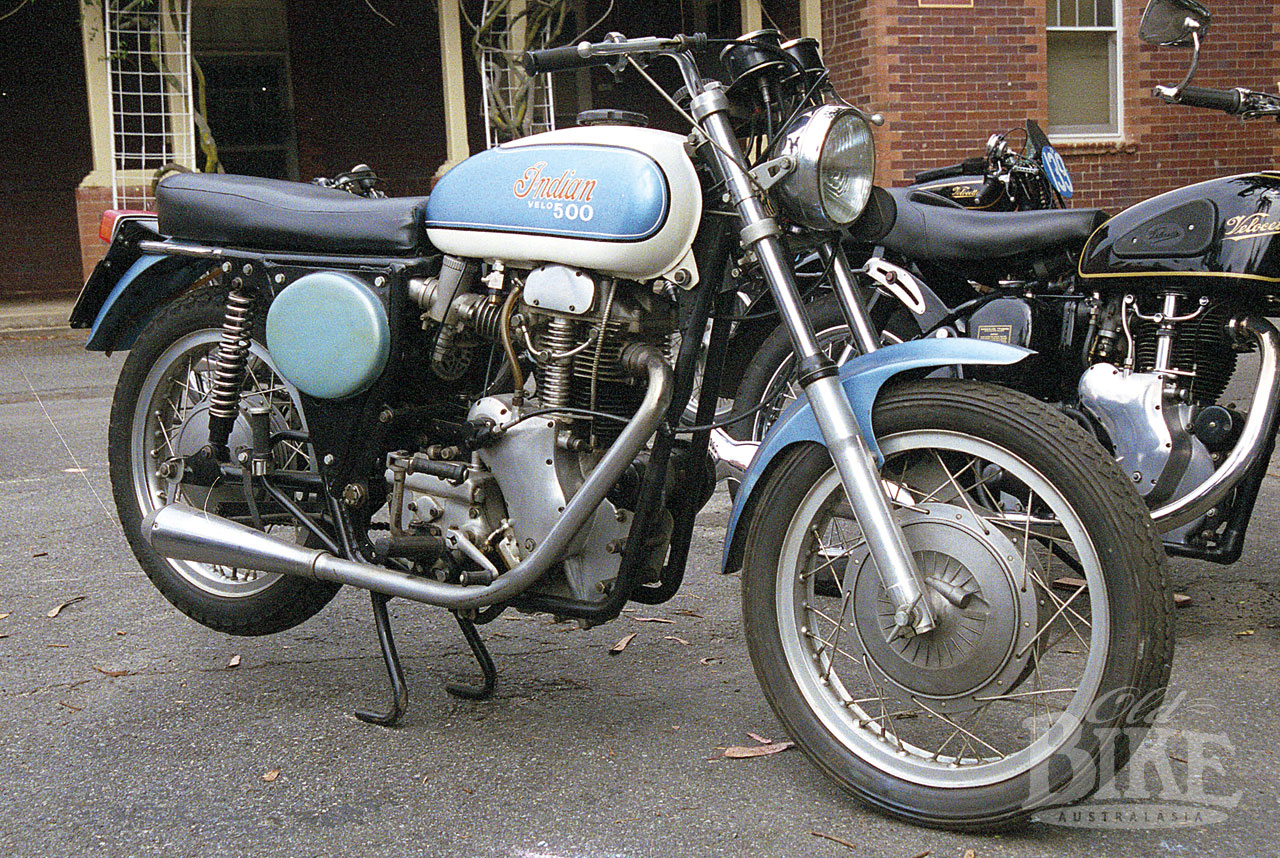

Commencing in 1969, the power units (originally just the Venom engines but later, as things began to dry up, Thruxtons) were shipped to Italjet’s factory in Bologna, there to be mated to Tartarini’s chassis. The frame was a rather handsome affair, very much in the Featherbed mould, with a full steel tube double cradle and conventional swinging arm. The frame even had a look of Velo about it, with squared off front loops rather than the more rounded Norton style) but was a whopping 20 lb (9 kg) lighter than the old Velo unit with its heritage-listed lugs and brackets. The entire bike scaled in at 45 lb (20.5 kg) under the standard Venom. The first few bikes to be completed even used Tartarini’s own front forks, but these were soon replaced with Marzocchi front and rear suspension, state-of-the-art at the time. The original specification called for a Campagnolo twin disc front brake, which looked for all the world like a drum, but the vast majority of the production run used a big, and heavy, Grimeca twin-leading-shoe front brake, with a single shoe Grimeca on the rear. The rear brake was a curious system with the lever pushing the cable inner rather than the normal practice of pulling the outer. Borrani alloy rims were standard fitment.

Fibreglass abounds; on the front mudguard, side covers, seat base and rear guard, while the fuel tank is steel. Hidden under the left side cover is the battery, with a standard Velo oil tank under the right, leaving no room for a tool kit. Instruments were the ubiquitous Smiths speedo and tacho, found on the Velo Thruxton/Sportsman and many other Brit bikes of the era. Instead of an ammeter, a warning light in the headlight foretold of electrical woes. One departure from standard, traditional Velo practice was the muffler. In place of the usual fishtail was a serious looking reverse-cone megaphone, with precious little inside except air.

Road tests of the day praised the overall handling, panned the Tartarini forks as far too stiff, loved the throaty bark from the megaphone, and universally slated the price. When a brand new four-cylinder Honda CB750 could be had for US$1495, the Indian Velo chimed in at US$1450 for the Venom-engined job, and an extra $100 for the Thruxton. No amount of nostalgic vapour was going to bridge that abyss, and the big single found longtime residence on dealers’ floors. The final batch of around 50 could not even be placed in USA amid fears of spares for the now-defunct Velocette marque, and was sold as a batch early in 1971 to London dealer Geoff Dodkin, who sold them for £525 with a Venom engine or £550 with a Thruxton.

Thus the Indian Velo project joined Velocette itself in the graveyard of gone marques. Gone they may both be but Velocette is certainly not forgotten, while the Indian Velo is such a rare beast that it stops people in their tracks, nearly 50 years on.

Down under examples

Given the production run of around 150 complete bikes, a surprisingly large number exist in Australia, all privately imported. There appears to be no standard colour scheme. Gold/white is not uncommon, but there are also blue, bronze, and even one in very Velo-esque black with gold pin stripes. The featured model here is one of the rarest, being fitted with the Thruxton engine and close-ratio gearbox. It is owned by Jon Munn at Classic Style in Seaford, Melbourne, and has been the subject of a complete and very professional restoration. Jon even scoured the world to find original examples of the slotted screw that hold the side covers – refusing to give up until he had found a set. The Thruxton engine, with its revised inlet port and big 1 3/8” Amal GP carburettor, only fits into the frame by way of a factory tweak that cranks out the centre frame tube slightly to allow the bell mouth to pass through it.

Alan Harper’s Indian Velo is especially significant in that it is the second one produced – engine number (6486?). It differs from Jon Munn’s later model in several respects, not just that the engine is the standard specification Venom rather than the racier Thruxton, and is fitted with an Amal Concentric carburettor instead of the GP. The engine actually sits vertically in the frame (as on ‘factory’ Velocettes) instead of being canted forward a few degrees on the majority of the Indian run. The exhaust pipe is squared off rather than swept back and is higher at the rear, and the petrol tank, which on the Thruxton version is visually similar to that used on the Velocette Scramblers, is a rather angular type. Both tanks barely clear the rocker box! Alan’s bike also has the standard style straight leg Velocette centre stand, while most others have a curved ‘roll-on’ type. This one is fitted with a magneto instead of the usual coil.

Specifications: 1970 Indian Velocette Thruxton

Engine: Velocette 500cc ohv single

Power: 41hp at 6,200 rpm

Bore x stroke: 86mm x 86mm

Gearbox: Velocette 4 speed.

Carb: Amal GO 1 3/8”

Ignition: Coil and battery

Frame: Italjet tubular steel double cradle.

Suspension: Front Marzocchi telescopic Rear: Marzocchi units with 3-way spring pre load.

Wheels/tyres: Front: Grimeca sls brake, Borrani rim 3.50 x 18 Rear: Grimeca sls brake, Borrani rim 4.00 x 18