Derek Pickard looks back at how Honda produced the ace card which changed the motorcycle world and why its end was so downbeat for one of the greatest-ever milestones on two wheels.

The biggest single move in Honda’s life began in late 1967 with the shock announcement to pull out of Grand Prix motorcycle and car competition. The decision saw truly innovative and competitive machinery disappear and allow the European bike GP circus to become boring again.

Honda’s move was not about saving money but taking a quantum leap in building its business. Many of the company’s most talented engineers were tied up in the massive race programs and their abilities were needed back in Japan where the company was planning the biggest single knockout punch in the history of motorcycling.

So it was all hands to the pump in late 1967 in a hurried program to produce what became their biggest ace card. Within an amazing 12 months the prototype CB750 made its debut at the Tokyo motorcycle show and the photos went around the world.

But this was no “show special” as Honda had not only come up with an incredible design but it was also putting the final touches to an all-new production line. In little more than another year, motorcyclists from US to Europe to Brazil and Australia were riding the CB750.

The market reaction was massive. Everyone was knocked over. Early factory estimates on demand were wildly inadequate. This forced the same R&D team to quickly reconfigure production ability to get many more bikes out of the doors and onto ships. The design became the basis of many other successful models and Honda made a fortune.

What the press said

Initial reaction to the Tokyo motorcycle show pictures was the predictable wow and fabulous, as Japan’s top bike maker quickly showed what it had been doing behind the scenes during 1968. When the first test bikes arrived in the major markets within a year, the amazement continued.

This bike had the lot: 750cc big capacity, 4 cylinders, overhead cam, 5 gears, electric starter and front disc brake. Nothing came close. On the road it totally delivered with smooth power, excellent performance and superb durability. Only the most one-eyed Commando, Trident and Harley fans failed to see the superiority of the new bike.

Magazine testers respected Honda’s ability to produce successful multi-cylinder racing bikes and here was an equally innovative road machine. They all loved it. Honda did very little advertising as the test reports overflowed with praise.

Here was a bike that could reach nearly 120mph with scorching acceleration yet needed minimal servicing. It didn’t vibrate, didn’t leak oil, had electrics which kept working and always started on the button. At everything which could be measured, the all-new big Honda was totally superior.

I first put a leg over one in late 1969 while working for a London magazine and experienced everything which could be hoped for from Honda. Although I was critical of the size and weight those problems were completely countered by the easy starting, incredible smoothness and wonderful spread of real power. Better still, after months of thrashing the four carbs didn’t drop out of tune which meant the sweet running continued. Everyone who did a job like mine around the world was knocked over. This was definitely the next stage in two-wheel excellence and testers advised any enthusiast who could raise the money to buy one.

Unusual design

There was nothing sensationally revolutionary about the CB750, except that every advanced feature was used in the one motorcycle. The only surprises in the design were the use of layouts thought un-Japanese: a slightly long stroke motor, a primary chain to the clutch and a dry sump lubrication. These three factors were certainly strange to modern Hondas and no one expected to see them emerge on a new large model. In reality, they all worked okay as the small bores ensured a minimal overall engine width and the individual cylinders of little more than 184cc allowed high revs, the primary chain lasted long enough and the pipes to the oil tank neither leaked nor broke.

Smartest of all makers

When the CB750 hit full hi-volume production in 1970, Honda management yet again showed the ability to get it right. They not only left a big R&D team to come up with other configurations of the same four cylinder design but put the majority of their engineers onto another innovative project. For some years, the company had been producing mainly quirky little engined cars which while satisfying domestic demand, were not suitable for many export markets. Honda needed a 4 wheeled ace card and so the huge team were tasked with the job of developing what became known as the Civic. Although more humble in performance among the car industry than the CB750 was to bikes, it was an excellent product, was made in huge numbers, proved an instant success and set the company on its path to do great things in the auto industry.

Pulling out of Grand Prix racing in 1967 and embarking on a five year R&D big bike and mass-appeal car program was the smartest thing Honda ever did. What to many was previously an interesting little Japanese company was soon to become a truly global operator. Although Mr Soichiro Honda loved racing, he was obviously a very smart businessman. No other petrol headed enthusiast has presided over the growth of such a massive auto empire which now boats many car and motorcycle factories all over the world.

Early production and K numbers

Honda had no way of predicting how many CB750s would sell. They knew their new bike had to be a success because the opposition was so dated. Accordingly, the first model was produced on a small production line capable of being expanded.

In terms of numbers, the first production forecasts were for a tentative roll-out of a rather humble few thousand annually. But within a month of announcing availability to their world-wide distributor network that initial number was seen to be totally inadequate and so the R&D team quickly put its Plan B into effect with more sophisticated production techniques. By the end of 1969 the line was achieving an incredible 3000 monthly. This was the reason why the first models varied the casting technology for the crankcases so much.

The R&D team were also working on upgrading the design and the few niggles with the first model were righted as early as 1970 and that upgrade was known as the K1 version. (There was no K0 model and for some people to claim so is a nonsense as K stands for the Japanese word kairyo which means improved-update.)

Within another year, monthly production numbers were reaching a staggering 5000 and with the Japanese currency languishing so low on the then exchange rates, vast amounts of foreign cash flooded into the company. The 1970s saw Honda – like many Japanese manufacturers – become exceedingly wealthy.

First Australian arrivals

Despite the fact that Australia is a very small market, we received early production units. The first came here in late 1969 at a time when the motorcycle business wasn’t controlled by international factory channels but only small, usually family-based statewide distributors. (As a point of interest, the very first to land was in November and went to Lindsay Urqhuart for use in a sidecar racer.)

As soon as CB750s began to appear, they were an instant status symbol. No one could miss the four cylinders and four separate exhausts. Everyone who rode a CB750 knew they had something very special. No amount of café conversions on an old British twin could make up for the reality of four cylinders matched with top quality and durability. The future had arrived in Australian.

Racing success came fast

Winning the big race at Daytona in early 1970 went a huge way towards putting the CB750 on the map. The all-new bike had beaten the bigger line-up from BSA-Triumph and Norton to prove its performance at one of the world’s most influential events. Every race enthusiast everywhere in the world wanted a Honda four, no matter what the price.

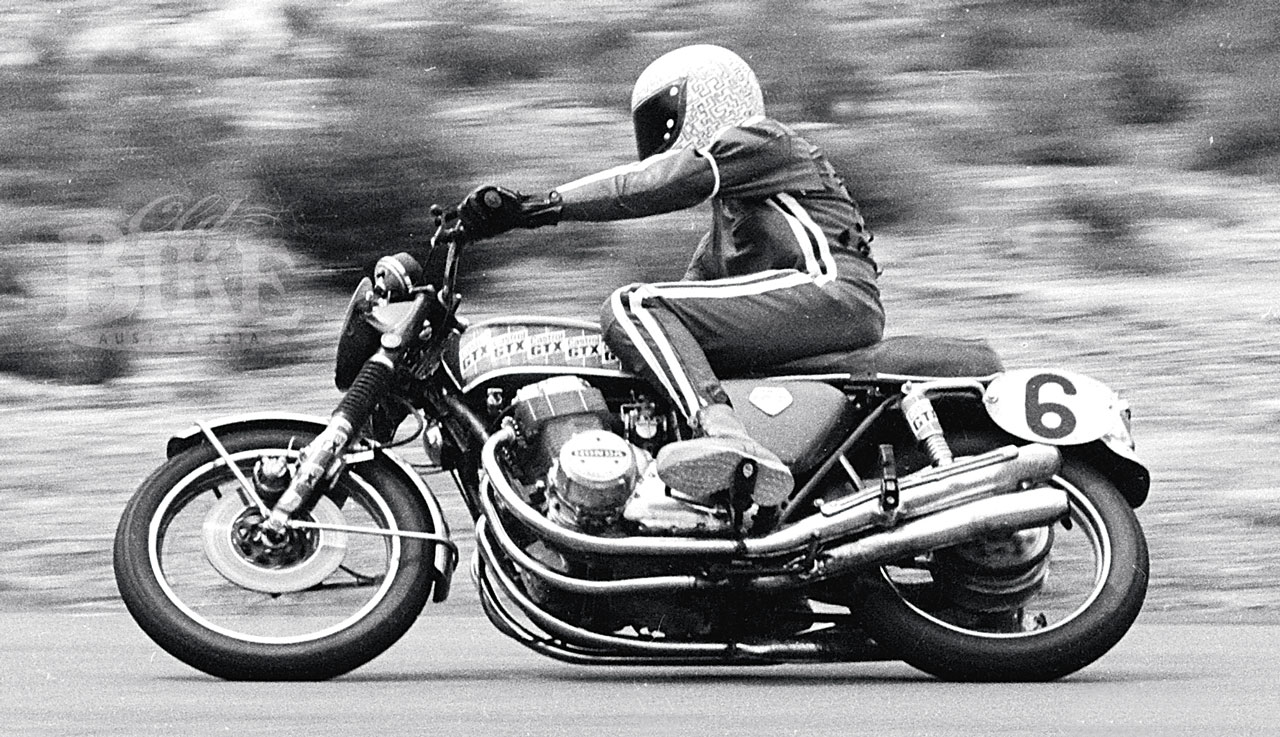

Here in Australia, the second Castrol 6 Hour race was won by a CB750 as by then the bikes began to appear throughout the country.

For the then-important Isle of Man production race, the arrival of the CB750 in the UK came too late in 1969 to make that year’s June event, but they were there in volume for 1970. That was the year I had my first sighting of such a racer as one was being prepared by George Fogarty (Carl’s dad) who also put in much testing as part of his bike’s development. He loved the power which could be reliably extracted but knew the problems lay in the frame and suspension. That year, those relatively heavy touring type bikes were no match for the dominant UK machines in their own back yard as factory

Tridents and Commandos were fully sorted with top riders and they dominated the Island. But with the input of many specialists, work on the fours went ahead very quickly and the fast Hondas went faster.

By 1971, the CB750 was not only THE bike to have on any track but they were available at every local dealer. They soon sported local 4 into 1 exhausts, stiffer front ends, better rear shocks and more engine power. Honda fours just kept getting faster.

That certain sound

In stock trim, the over-muffled 4 into 4 exhaust layout was nowhere near as sporty as the bike’s performance. Then came the 4 into 1 performance exhausts which set a new sound benchmark. The unique boom of the big Honda became as distinctive as the four’s appearance. Gone was the traditional exhaust beat divided up into either a single, twin or triple and in its place was the very different exhaust note of a high revving four.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch

The reaction of the British industry to the arrival of CB750 was typical of their too little and too late. Restricted by bad owners, bad management and bad unions, BSA Triumph and Norton engineers knew what to do but had no budget to put their wish-list designs into production. They were limited to relatively small modifications on old designs.

In 1971 BSA Triumph released their “new” triples which boasted upgraded frames, better forks and alloy drum brakes. And Norton’s action of adding even more cubes to their lumpy big twin with a disc brake was also completely inadequate. Both makers were soon to fail.

Anglo bike riders took a real beating. In one stroke the Japs had dealt a massive ace card which boasted size, performance and durability with complete ease of use. No longer could the lovers of the old twins claim any superiority. The sight of a dedicated Dunstall Norton 810 owner struggling to start his big twin alongside his push-button Honda 750 riding mate, illustrated the problems of the old against the benefits of the new. It was all over.

Building on success

Despite the fact that everyone was wanting and buying a CB750, the factory reacted to the criticisms of the one huge size being inadequate for the market potential. By 1972, Honda has finalised their sweet 500 four which was closely followed by the 350 four. In another couple of years the cute 400 became very popular. And they were followed by 550 and 650 versions. The one layout had become the platform for seven different sized models; that’s smart engineering, great marketing and big profits.

In a few years, Honda fours were everywhere. They were competitively priced, performed well, proved durable and did everything owners wanted.

Accessory makers had a ball. No sooner than 4 into 1 exhausts and loud mufflers came onto the market than just about everything else followed. The line-up included flatter handlebars, cuter seats, stiffer suspensions, oil gauges, etc. Race parts specialists also got into the act with big bore kits, wilder cams, bigger carbs, race-look fairings and the like. Rickman even made a complete chassis swap as the ultimate Honda four bolt-on upgrade.

Clocking the distance

Despite the belief by the Brit bike lovers that rice burning Jap crap wouldn’t last, these Honda fours proved incredibly reliable. Apart from the important job of properly balancing the four Keihin carbs, looking after a CB750 was straight-forward. The work was no more than changing filters and oils as well as valve clearances and cam chain adjustment.

It soon became clear that the big fours would clock big distances without any trouble as this was a faster for longer bike. The Honda four not only set new standards in design but completely re-wrote the book on durability. Here was a Jap bike which could be as trouble-free as a BMW.

Weaknesses were few. Obviously the rear chain had a hard job to do with so much torque and weight, but riders accepted frequent replacements.

Inside the engine, the primary and timing chains lasted longer than many predicted. But a thrashing rider who neglected servicing found the cam chain and its adjuster to wear and replacement was very expensive. And too often that job led to bad workmanship where Silastic was used as the sealant that allowed little bits to block the small oil jets to the cam and an even more expensive job followed soon after.

An unfortunate failure incurred by some owners was a leaking head gasket. This was the result of the long top end thru-bolts allowing some movement in the way the head sat on the barrels and the barrels on the case. A full top end tear-down was the only cure and if that job had Silastic used or the camshaft oil jets not properly maintained, then it all had to come apart again for an even more expensive repair job.

Putting everything into perspective of what gave trouble and when, if a CB750 was ridden for years with good servicing, the following wore in this order: Balancing the carbs was vital for a sweet running motor and only an expensive 4 vacuum gauge set-up kept everything right; Back sprockets and chain; Exhausts rusted and needed replacement; A 4 into 1 was cheaper; Rear tyres never lasted very long if the power was used; Rear shocks faded but Konis were popular throughout the 1970s; Cam chain began to make itself heard and many were ignored; Front forks began to leak oil but new seals were relatively cheap; Primary chain inevitably became a little rattly but was usually ignored; When the top end of the motor wore with big miles or lack of camchain/valve clearance adjustment, it demanded valve work, new cam chain and adjuster and head gasket.

Then came the opposition

After having the big performance bike market to itself for a few years, along came the Kawasaki 900. This new kid on the block was bigger, strong, better, faster. Surprisingly Honda did little to counter the rocket Kwacker and so handed the top end of the market over to the all-conquering new Zed bike.

A few years later, when Kawasaki enlarged its 900 to a 1000, so Suzuki came along with an excellent 750 followed by 850 and 1000 versions. And as all this was happening, the CB750 began to look old, dated and slow.

Stayed too long

If the CB750 arrived with a bang it certainly ended with a whimper. Or to put it more accurately, the model was held for far too long. By the time the replacement CB750 and sister 900 with 16 valve DOHC engine arrived in late 1978, the old single cam long stroke had been around for nearly a decade. Admittedly other big Hondas had come along in the meantime (like the innovative Gold Wing and the incredible CBX1000) but the Japanese giant had allowed rivals Kawasaki and Suzuki to take huge sales due to their releasing better sport fours earlier.

The last versions of the famous Honda 750 – called F1 and F2 – were no more than minor factory upgrades with a few add-ons, none of which were major improvements. There is no doubt the last models in the late 1970s were good bikes but the pace of change had quickened, the competition was keener and so the prettied-up old CB750s deserved their dwindling sales. That is not to say the factory 4 into 1 exhaust, rear disc brake and better styling were not good, it is just they were not good enough. Bigger and better fours were available for much the same price.

I remember sitting in the London office of a bike mag I was working for during 1977 and taking a call from the local Honda HQ. They were grumbling at our unwillingness to run a major test feature on the then latest 750 and I was justifying our actions on the basis of the bike had nothing much new about it. I insisted a 4 into 1 exhaust, rear disc, seat styling and matt black engine paint had become terribly ho-hum compared to what the opposition was doing. The Honda man eventually slammed the phone down on me, presumably because sales of the CB750 were sliding fast and no one was willing to help. That’s called competition.

For a bike which had earned so much praise, pioneered so much new ground, set so many high standards, won so many admirers and earned Honda so much money, the limp last years of the CB750 in 1977 and 1978 were a pity. Honda was a couple of years too late in releasing its replacement which saw the old CB750 finish its production life unable to compete against the emerging range of other high performing fours. The bike which had introduced such a high standard to the motorcycling world went out as a bit of a joke. Shame.

Buying a CB750 today

Many of the original bikes are nearly 40 years old so buyers should expect just about anything. Most 750 fours were bought new by relatively young enthusiasts keen to exploit the performance. Many had upgrades with a 4 into 1 exhaust being very popular. Most original 4 into 4 exhausts hung in garages until thrown out. Very few bikes kept their original exhausts. Accordingly, relatively few surviving bikes are original.

Total wrecks sell for just a few hundred dollars and concours rebuilds go for as high as $15,000 or even more. If you don’t mind a 4 into 1 exhaust and non-original paint, good bikes can be had for as little as $3000 with decent appearance costing over $5000.

Most top original Honda fours come from the USA where they were left in garages with relatively little mileage on the clocks. These have been arriving in big numbers through the various specialist importers for a few years. And apart from having speedos which read in miles, they prove good.

The alternative is to renovate, and like all such work, this can be incredibly expensive. The trick is realising the best way to build an excellent bike is to start with a very good one. Prospective buyers should wait for at least a complete one with as little wear as possible to come onto the market.

While there are a few local Honda four specialists with a reasonable stock of parts, it is the USA which has the most parts and the many suppliers in that country boast of being able to supply just about anything. The CB750 listings on ebay.com are always trawled by local enthusiasts wanting everything from exhausts to gaskets, to odd small fittings. And don’t forget to include searching the UK and German listings as many machines were sold there and those countries also have their specialists.

Fixing an old one

Let’s keep this in perspective, most of these bikes are over 35 years old so we have to be realistic. The previous list of: back sprockets and chain, tyres and shocks can be joined by fork seals and maybe chrome, swingarm bushes, steering head bearings, battery, disc and pads as well as a pretty serious engine rebuild. The latter will probably involve the bottom and top ends with primary chain and clutch basket replacements. That is at least a few thousand dollars which means a tidy looking $3000 bike is really $6000 plus some months work. Add the cost of a basic paint job and a replica 4 into 4 exhaust and you’re quickly talking a $10,000 spend. So if you’ve got a few months and $13,000 to spare, those are the numbers. Many enthusiasts spend well over $15,000 and up to a year but few admit it. Next time you see a cute low mileage one from the U.S. priced at $10,000 in at an importer’s warehouse, it is a bargain.

CB750: Future top Japanese classic?

For those looking for a big investment, this is probably not the model to go for because of the large volume of bikes still available and the fact that the twin shock CBX1000 has got a stranglehold on the top title. But because of what the CB750 did for so many, the model will always command top respect. It will always be referred to as the machine which introduced a huge step-up for mass motorcycling. No other performance model ever made such an impact.