Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

Straddle a Honda CB750 today and it seems like a nice compact package, certainly not overly large by current standards. Yet when it was released in 1969, the media applied descriptions like ‘huge’, ‘bulky’, ‘massive’ and ‘formidable’. And compared to the comparable tackle of the day – British twins, BMWs and the like, the CB750 probably was a bit on the porky side – wider at least than we were used to. It made no difference to sales, as the CB750 went out dealers’ doors by the truckload, but Honda listened to the few detractors and came up with an almost immediate solution – the CB500….

The Big H already had a 500-class contender in the DOHC CB450 twin, which was more than capable of staying with its Caucasian rivals, but the world wanted four cylinders, nothing less. Rather than produce a scaled-down, and thus overweight CB750, Honda started with a clean sheet of paper. Of course, the refinements that had made the CB750 such a hit were all there: a 100% reliable electric starter, disc front brake, powerful lights, big turn signals and superb finish, but one important thing was missing – weight. At 194 kg, the CB500 was over 50 kg lighter than the 750, and it felt it.

Outwardly straightforward, the CB500 engine was all-new and inside it contained some innovative features. With vertically mounted cylinders rather than the forward-included cylinders of big brother, the 500 had a more pedestrian look about it. Four 22mm Keihin carburettors controlled by a single cross shaft removed some of the bugbears of the CB750 multi-cable set up, although a common complaint was that the return spring was overly strong and made prolonged full throttle riding a chore. Nevertheless, the system made carburettor synchronisation decidedly easier.

Honda had set out to make the 500 a quieter engine than the 750, and one change was to replace the 750s front cam chain roller with a rubber slipper cradle. A relatively high 9:1 compression ratio was achieved with shallow combustion chambers in the two-valve head and fairly flat-topped pistons, resulting in a cleaner burn and lower exhaust emission levels – an issue that was beginning to raise its head in the US market. Downstairs, the five-main bearing crankshaft assembly mirrored that of the 750, with the two outer throws at 180-degrees to the two inner. An alternator hung from the left end of the crankshaft, with twin contact breaker point on the right. To connect the crankshaft to the five-speed transmission, a Morse chain driven by tiny sprockets with rectangular teeth set in rows of six and five provided an almost silent assembly with high load carrying characteristics. Inside the sprocket on the gearbox end, rubber shock absorbers further smoothed out the engine’s firing loads. A major variation from the 750 was the employment of a wet sump instead of a separate oil tank, which was claimed to keep the oil cooler and eliminated the external oil lines of its big brother. At a quoted 50 bhp at 9,000 rpm, the CB500 was, on paper at least, no rocket ship, but it was a willing revver and when stokes, covered the ground quite quickly.

With all the attention to detail in the transmission, the CB500’s gearbox is not exactly the smoothest to come out of Japan. Down changes, particularly when pressing on a bit, were stiff and clunky, with a very solid pedal action. The clutch too, would slip when pushed hard.

The oversquare (56.0 x 50.6) dimensions kept the overall engine height low compared to the 61 x 63 750, meaning that the cylinder head could be removed with the engine still in the frame. This proved rather handy, because as CB500s racked up a few miles they tended to weep oil from between the head and cylinder block. The cure, facing both surfaces, was relatively straightforward, and sometimes had to be performed under warranty, so not having the remove the entire engine/transmission unit was a blessing. Another thing that showed up after a bit of use was the tendency for the mufflers to rust out around the rather ornate fluted ends and where the small balance pipe linked the two ‘trumpets’. It created a flourishing turnover in after-market, usually four-into-one, exhaust systems, which in turn has made original pipes in good condition rare and expensive for restorations.

When new, the front disc brake, which at 260mm was 20mm smaller than the 750, worked very well, but as time went on its efficiency seemed to dissipate due to the combination of the stainless steel rotor and the pad compound. The rear drum, sourced from the CB450, was an excellent fade-free unit, which was just as well, as it was called upon to do quite a bit of work.

Just like on the CB750, the CB500 handlebars were generally considered to be too high, and dealers did a roaring trade in swapping these for the genuine Honda ‘touring bars’ which looked like the traditional British one-inch rise style. This modification also required fitting a shorter clutch and throttle cable, and preferably a shorter top hydraulic hose to the master cylinder. It did however, transform the riding position and hence, comfort of the CB500 as a tourer as the rider no longer had to sit upright and exposed to the wind. The wide, flat seat was well padded and comfortable for rider and passenger alike.

The chassis package is something Honda definitely got right on the CB500, which could be flicked around effortlessly, thanks partially to the 55.3 inch wheelbase – 2 inches shorter than the 750. The all-new front fork had well chosen spring and damping characteristics and the rear shocks coped well, at least when new. Once again, a few miles on the clock seemed to prematurely age the rear end. Winding the springs up to the maximum preload worked for a while, but a set of Koni shocks was the real answer. The biggest difficult was in carrying a pillion passenger, when the rear shocks would bottom repeatedly. The sweet handling was undoubtedly mainly due to the frame geometry and stiffness, although the swinging arm, fabricated from two pressings and welded together, was no lightweight item.

For those who had graduated from British tackle, the standard of refinement on the CB500 was sublime. Each of the big instruments emitted a soft glow at night, while a panel of four different coloured lights indicated turn signals, oil pressure, neutral and high-beam.

From tourer to track

Honda tantalised the world with a sneak preview of the new CB500 at the San Diego Motorcycle Show in April 1971. In Australia, the first CB500s arrived around September, just in time for the second running of the Castrol Six Hour Race at Amaroo Park.

Although not touted as a sports machine in the 500cc class that contained rapid two strokes from Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki, the Honda had a big advantage in fuel consumption – around 50 mpg even when pushed hard.

In 1971, I was a Honda dealer in Gladesville (near Ryde in Sydney’s inner west), and attended the local launch of the CB500 at Bennett Honda’s ramshackle headquarters at Mascot. There I ended up in conver-sation with fellow dealer Paul Giles, who had a Honda shop at Richmond. Paul was a rather loquacious and outspoken person, but a fervent enthusiast and died-in-the-wool Honda man and baited me with a suggestion to enter a CB500 in the up-coming Castrol Six Hour Race, with comments like “You’re just an old scrambles rider Scaysy, you wouldn’t know how to ride a road bike fast!” Gilesy (everyone called Paul ‘Gilesy’, a moniker that has passed to his son Shawn) spoke at such a volume that everyone in the vast tin shed that was the NSW Honda HQ in those days could hear every word. Presently George Pyne, the NSW Sales Manager and a great friend of mine, sauntered over and said, “OK Gilsey, I’ll do you and Scaysy a deal on a 500 if you’ll both ride it in the Six Hour,” and he did.

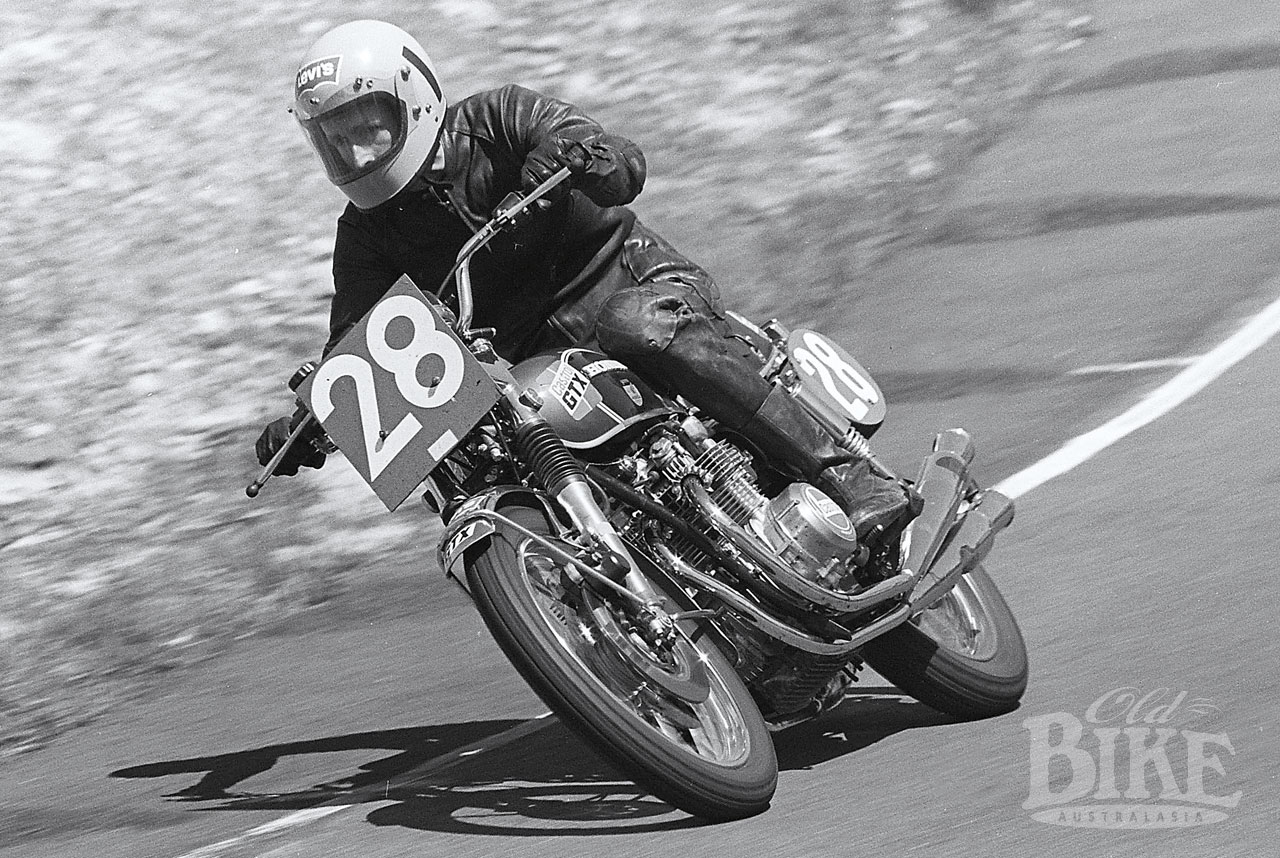

So a few weeks later we fronted at Amaroo Park with a brand new jade green CB500, which Paul had run in at his usual rapid lick between his shop in Richmond and his home at Bilpin in the Blue Mountains. We weren’t the only ones to enter a CB500: Ross King and Ian McLeod had one, as did Bill Burnett and Ian Cameron, with a fourth for John Bellamy and Robert Symons. The CB500s weren’t quite as quick as the two strokes, but once wound up there wasn’t much in it over a lap of Amaroo, and the Honda certainly had a big advantage in fuel consumption and hence, fewer pit stops.

In the race, our team ended up disputing the lead in the 500 Class with the Burnett/Cameron CB500 and as the event reached its final half hour, we had managed to pull an advantage of about a quarter of a lap. Then, just as we were preparing to uncork the champagne (or probably, a tinnie), Paul came into the pits complaining of a strange noise from the front end of the bike. A quick inspection revealed nothing more than the little wire loop on one of the mudguard stays (to guide the speedo cable) had come adrift, so I jumped on the bike and back onto the circuit as the rival Honda sped up the hill – ahead of us! And that’s the way it finished, a victory thrown away for us, but a 1-2 result for the new CB500 nonetheless. Paul and I didn’t see eye to eye on this outcome.

One year later, possibly still smarting from the result, I decided to enter the Six Hour again, using a rebuilt CB500 that had been in our workshops after a smash and subsequently repaired. This time my partner was Brian Martin, one of the bunch of Kiwis that had escaped from Wellington a few years previously – a talented group that included Ross King and Craig Brown. Paul Giles entered his own CB500 with Garry Davis as co-rider. One problem that had shown up in 1971 was the tendency for the clutch to slip, and such was the Six Hour scrutineers’ devotion to duty that little tricks like packing the springs out to increase pressure on the plates were bound to be discovered. Our remedy was to have new stronger springs wound, which were identical down to carefully applied yellow paint as on the originals. Totally illegal of course, but part of the Six Hour challenge was creative rule-bending!

The clutch mod worked well, but it made no difference to our fortunes in the race. When the engine was reassembled, a wire from the alternator got jammed between the cover and the crankcase, meaning that the battery progressively went flat towards the end of practice. Naturally a change of battery only produced the same result in the race, and it was only after the 500 spluttered into the pits that the real problem was found. This took some time to rectify, putting us totally out of the picture in the race, but we decided to head back into the fray, just for fun. Probably trying too hard, I got myself involved in a three-bike accident at (ironically) Honda Corner, and that was enough for me. But Brian, fit and energetic chap that he was, sprinted over to the wreck, pushed it back to the pits, kicked it basically straight and briefly rejoined the race on a bike that was a few inches out of track, before he too gave it away. Almost simultaneously to my get-off, Paul Giles dropped his 500 entering the main straight, trapping his hand under the handlebars and losing part of a finger. How fortunes change in just twelve months…. fuel advantage or not, the CB500s were totally outclassed in 1972 by the H1 Kawasakis, which finished 1-2 in the 500 class.

One for the birds?

Story: Sue Scaysbrook

I was quite happy with my little CB175, until an altercation with a truck on Manly Corso altered its shape a bit.

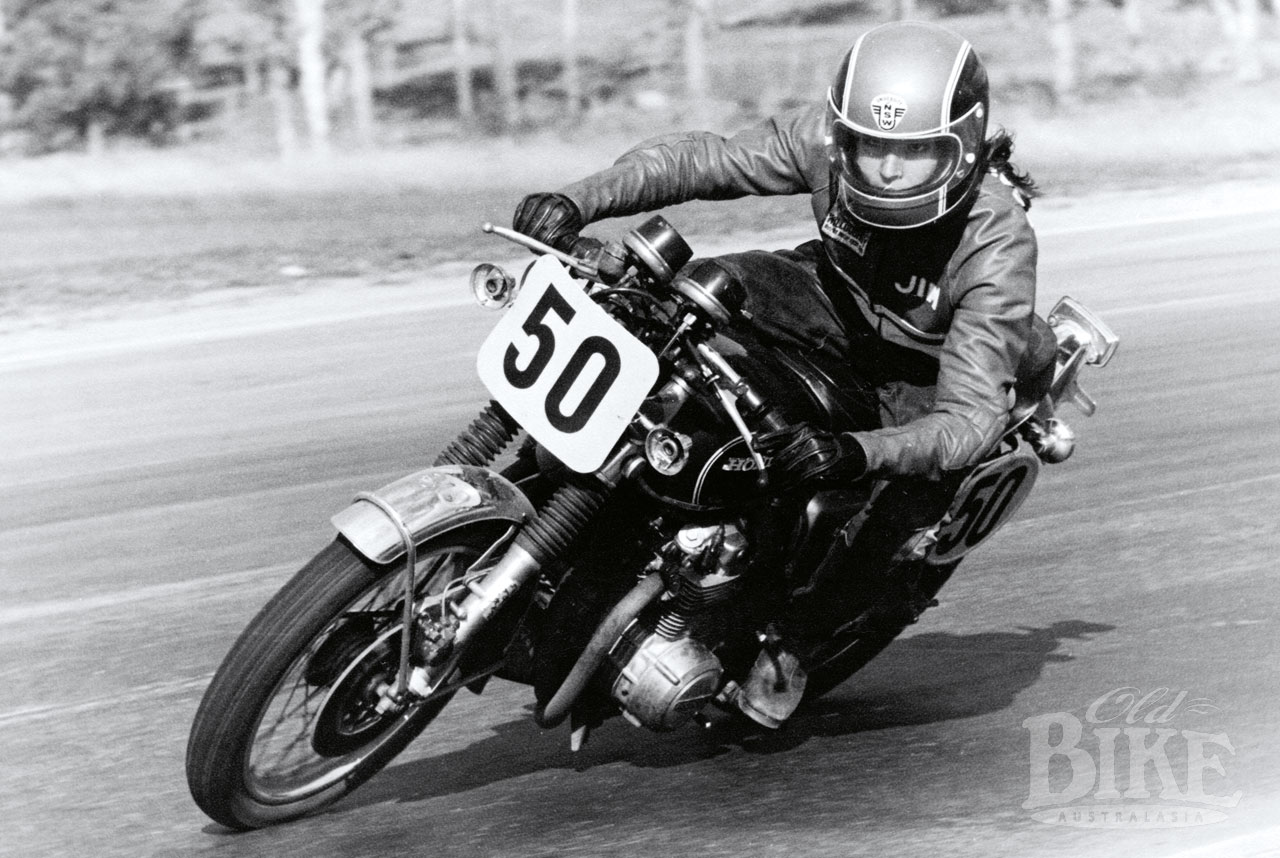

A friend straightened the forks, but it never felt the same again, so I went back to the shop I’d bought it from, Hondaland at Chatswood, and traded it on a new, green Honda CB500-4. That was in 1972, and working two jobs it meant that I would own it by 1975. The salesman at Hondaland, who was very popular with us girls, was Brian Martin, but soon after I bought the bike he moved across to Gladesville to work for Jim Scaysbrook at his Honda dealership, so when the 500 needed servicing, I took it there. I asked for Brian but Jim said he was busy and that he would look after me. You can see by my surname that he did. Anyway, this is supposed to be about the bike. I loved it, with so much power after the 175, and when the exhaust pipes rusted out, I had a four-into-one system fitted which seemed to give it even more power. It certainly made a lot more noise. At the same time I also had a set of flat handle-bars fitted and I even took it to Oran Park and raced it in a University Club day – wearing Jim’s leathers!

The 500 went to Bathurst at Easter a few times and lots of other medium distance rides, as well as being my only means of transport for work. It was a brilliant bike and never let me down, but eventu-ally I decided it had to go and traded it on a 125 Honda 2 stroke trail bike (MT125). Wrong! That was such a disappointment that I got rid of it and lost interest in riding bikes for a while, although by that time I was Mrs Scaysbrook and there were plenty of pillion rides on bikes from the shop.

When we made the move out of Sydney about seven years ago, we discovered all these fabulous coun-try roads literally at our front door. Jim still had his old Velocette which was eligible for Historic registration, and he saw a CB500 advertised for sale – a green one just like mine – so we bought it. Now it is Historic registered too and every Easter I jump on it and join in the Vintage Motorcycle Club’s Easter Tour, which is based at Bathurst and uses lots of the great roads near to us. I keep telling Jim that this one is not as quick as my old 500-4, and we should put four-into-one pipes and dropped bars on it, but he insists it has to be standard. It probably goes as fast as I need to, and to me it is still a gorgeous looking bike.