The Isle of Man mountain course is unique in its sheer abundance of natural hazards, which are rarely tolerant of errors of judgement or mistakes. Those who have taken on the Mountain respect it, for very few have ever managed to get every bend, every corner perfectly right every time. In 1951 it almost took the life of one of Australia’s greatest racing men. The resulting accident was so bad few thought he would ever race again – yet Harry Hinton fought back and in the following years achieved what are arguably his greatest victories. “A bit of a determined bugger”, was how Harry was so succinctly described by his close friend Eric McPherson – a remark that so accurately sums up the character of ‘Hinto’. And a massive understatement.

Story: Peter Rhys-Davies • Photos: OBA archives

Born in Birmingham in 1910 (Harry’s family emigrated to Australia in 1919), by 1951 at the ripe age of 41, Harry Hinton’s enormous talents as both a brilliant rider and mechanic/tuner had earned him a well deserved place in the prestigious Norton ‘Works’ team. Then headed by the incomparable Geoff Duke, Harry was the fourth member of the team, offered a ride on a 350 Manx – and was also promised a ride in the Senior was well. Earlier in the year in the N.S.W. TT, held at Bathurst, Harry, riding a Norton, won the Senior by almost half a minute, as well as setting a new lap record at 3 minutes, 3 seconds. To cap off a fine day Harry also comfortably won the ‘All Powers TT’, over 80 miles from Lloyd Hirst on his 1,000 cc Vincent, taking a further second off his lap record. With these victories under his belt Harry set off for the European season.

This was to be Harry’s third year in the Isle of Man, when on both previous occasions he had ridden private Nortons, owned by Hazel & Moore, the Norton dealers in Sydney, and had been an official Australian Isle of Man TT Representative. In 1949, at his first attempt at the famous course Harry achieved a very creditable 15th placing in the Junior. In the Senior Harry did even better: 9th at 81.78 mph, behind the winner Harold Daniell, who averaged 86.93mph. Well pleased with his first attempt, Harry returned in 1950, achieving two 10th places in the Junior and Senior. The new ‘Featherbed” frame Nortons swept through the Grand Prix races that year, but Harry’s great efforts on the old “Garden Gate” Norton had not gone unnoticed.

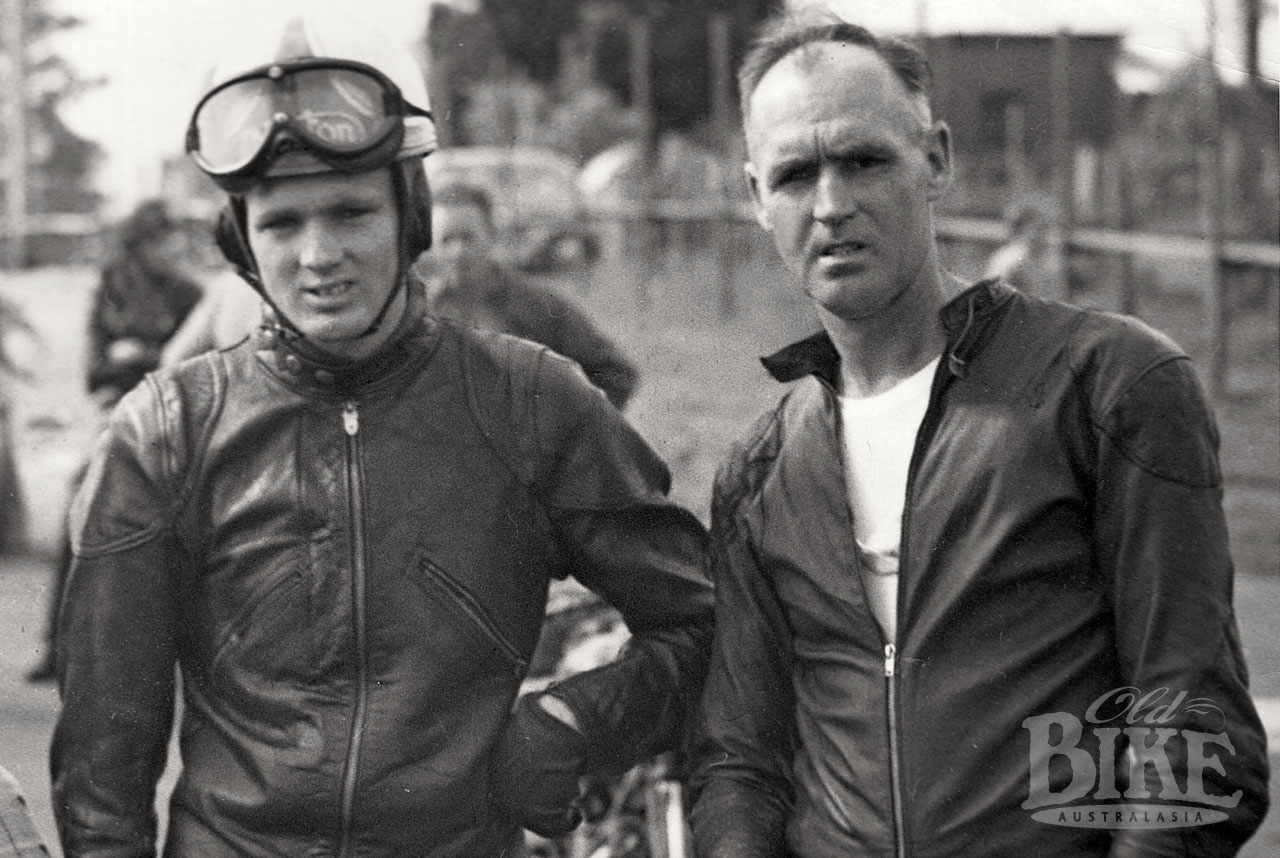

From among the dozens of aspiring riders striving for a place in the Norton works team, Harry Hinton was chosen for 1951. This was after a couple of brilliant rides during the previous season on loaned ‘works’ machines, at the Belgian and Dutch races of the World Championship series. During practice for the 1951 Isle of Man Tourist Trophy races Hinton was placed consistently in the fastest three in the Junior class, on several days setting the fastest lap, and astonishingly had (unofficially) broken the 250cc lap record by 63 seconds riding Maurice Cann’s Moto Guzzi. Harry must have been quietly confident as they lined up for the Junior TT. Michael Kirk, of “The Motor Cycle” takes up the story. ‘This year there is actually a number four works Norton. By perhaps unprecedented compliment it is allotted to a Dominion rider, Harry Hinton, the Australian. He was good when we first saw him. He has got better at each outing. This year, astride a pukka factory bus, he is dazzling’.

On the opening lap Harry was just 33 seconds behind Geoff Duke, and 3 seconds in front of fellow Norton team mate Johnny Lockett. At the completion of lap two Harry Hinton was exactly one minute behind Geoff Duke, and had increased his lead over Johnny Lockett to 19 seconds. Then tragedy.

‘Lap three opens with a semi-tragedy. Hinton, the brilliant Australian, spills along Laurel Bank while lying second to Duke. It is no exaggeration to say the crowd would have seen almost any other rider out of the race.’ Harry’s son Eric is positive the cause of the terrible accident was a rear suspension unit on the Junior Norton suddenly seizing. Much of Harry Hinton’s left side was badly damaged as he raked along the road, splintering his kneecap, with his hand and arm suffering multiple fractures. In truth, he was lucky to be alive. Laurel Bank is a nasty right hander some ten miles out from the start, and luckily there was an ambulance close by. Many weeks were spent in Noble’s Hospital, with no-one seriously considering Harry would ever be able to race again. He had lost the use of almost all movement in his left hand, and his left leg could barely be bent at all. One of the many friends who visited Harry in hospital was Tony McAlpine, another of the Australian Reps that year. He went back home at the end of the racing year firmly convinced Harry Hinton’s racing days were well and truly over. But Harry had other ideas. Being a ‘very determined bugger’ he was back on the race track the following year – but he never raced overseas again.

It had been a long hard struggle to that ‘works’ ride in 1951, beginning way, way back in January 1926. Harry was then a member of the Western Suburbs MCC, and competed in several road trials, two being of six days duration. Another popular activity was beach racing. At low tide there were many long stretches of beach which, with care, could be used for all kinds of racing. It was usually pretty basic – just a dash up to and around a pole and back, but for a young boy it was fantastic. Harry was working as a delivery boy for Harringtons, the film distributors, driving a sidecar outfit, and when the firm of Moffat Virtue bought a brand new 1930 Indian Scout outfit, they offered a job of delivery boy to Harry – a position he eagerly accepted. In 1931 he was driving the Indian Scout outfit at the corner of the Registrar General’s office in Sydney, when a car came out from a side road, smashing into the sidecar, hurtling the machine across the road out of control. It hit a wall and Harry was thrown off, but his face caught the end of the handlebar, and one eye was almost torn out of its socket. At the hospital that eye had to be removed to save the sight of the other one – and through all of Harry’s great racing career he had the sight of only one eye! Harry claimed that a few years later, suddenly and without any warning, stereoscopic vision returned to his one eye. Whether it did or not, it is without question that Harry’s racing judgement, braking and cornering, was unparalleled, and on the usual dusty, gravelled roads then used for racing, this was an extraordinary achievement.

After Harry left hospital he was offered a position with P. & R. Williams, the AJS and Velocette agents, a side benefit of which was a ride on an OHC 498cc AJS at the inaugural Easter race meeting at the Vale Circuit at Bathurst, but soon took up an offer to work for Hazel & Moore in the workshop, re-conditioning used motor cycles. For each machine completed Harry received Two Pounds and Ten shillings. Through Hazel & Moore Harry bought a used 490cc overhead camshaft International Norton, stripped it of lights and anything else unnecessary – and went racing. In 1933 he went to Phillip Island in Victoria for the Australian Grand Prix. His Norton seized when he was holding second place in the Senior, but a little later in the day he borrowed a 350 Norton and won the Junior Grand Prix.

Bennett & Wood had been and were to be for many years the BSA agents in Sydney. In 1933 BSA brought out a new OHV sporting model, in 250cc, 350cc and 500cc capacities – the Blue Stars. To help publicise these new sporting singles Bennett & Wood approached Harry, so at the age of 22, he left Hazel & Moore to become the BSA Number One ‘Trade’ rider, working as a mechanic in the Bennett & Wood workshop. Probably more than anyone, Harry did so much to help publicise the BSA range of motorcycles, but results were rather slow in coming. The best Harry could accomplish at the 1934 Australian TT races on the Vale Circuit at Bathurst was a 3rd place in the Junior, behind Don Bain and Art Senior. At Bathurst in 1936 the best Harry could accomplish was 3rd in the Senior behind the acknowledged experts Leo Tobin and Don Bain, both on OHC Nortons. Only someone with Harry Hinton’s grim and determined perseverance, and undoubted skill, could have accomplished as much as was done with that pushrod BSA.

It was customary then to run both the Lightweight and Junior races together, as rarely were there enough 250s to make a full race field of their own. In 1937 Harry chose to ride his 250cc BSA, with that race being run over ten laps of the Vale circuit, while the Junior went on for another four laps. From six starters in the Lightweight, only two finished, with Harry achieving his first ever win at Bathurst. Although Harry is best remembered now as a road racer, in his younger days he turned his hand to almost anything that equated speed with two wheels. In March 1936 the Showground Speedway organised to have a number of top road racing men demonstrate their capabilities, by putting on three ten lap heats. These were for stripped road racing machines, and Harry won the Empire Cup on his 490cc BSA after winning all three races. At the Penrith Speedway he took out a second place in the sidecar event, again on his BSA.

By 1938 the new circuit at Mt. Panorama was ready, although not surfaced. Harry managed a second place in the Lightweight behind the very fast Velocette of Tom Jemison, but retired in the Senior. Though, using the same machine with a sidecar attached, he did win the Three Wheeler race as some compensation. With the threat of war in Europe looming the last races held at Mt. Panorama before they stopped for the duration were held at Easter 1940, and Harry this time won the Lightweight race.

Once war was declared most forms of motor sport were curtailed, but in 1941 Harry Hinton and Eric McPherson helped to form the Motor Cycle Racing Club of NSW. The club ticked over for the next few years, being resurrected fully in 1946 as racing got back into its stride. Over the next couple of years the ACCA began to set up the re-introduction of Australian Representatives for the Isle of Man TT races. A levy was placed on the gate entry to all motor cycle competitions held throughout Australia, with this money going to what was known as the ‘Isle of Man Fund’. The top Australian riders naturally wanted to race there, but it was an expensive business, so the proceeds of the ACCA fund each year were split equally between the two or three nominated riders. As well, the ACU of England also provided 100 Pounds Start Money to each Australian Rep. rider – which helped to make the whole trip just about financially possible.

It was not until 1948 that the ACCA had sufficient monies in the Isle of Man fund to consider sending any riders overseas. All of the states were asked to nominate their top one or two riders, and from the five or six names put forward, three were chosen. The number one choice was Frank Mussett, the Victorian champion who had competed in the Isle of Man just before the war. Second on the list was Harry Hinton, who was by then riding Nortons with the sponsorship of Hazel & Moore. The third member of the team was Eric McPherson, Harry’s pre war BSA teammate. But from the three riders, only one went over to the Isle of Man that year. Mussett had to decline as he was deeply involved in building up his business. Harry was very keen to go, but Hazel & Moore were unable to persuade the Norton factory to set aside a pair of their production Manxes for an unknown Australian rider. That left just Eric McPherson.

Thanks to the efforts of Dick Hardyman, ACU Secretary Wally Capper, and P. & R. Williams, (the AJS and Velocette agents), McPherson was able to arrange for a 350 7R AJS and a 350 KTT Velocette to be made available to him. Unfortunately a crash in practice – it is thought that oil on the course brought him down – caused Eric to miss both the Senior and Junior rides that year. By 1949 the production of Manx Nortons had much improved, with the result that Hazel & Moore were able to arrange for a pair for Harry for the Isle of Man TT. Once again he had been chosen to represent his country, and this time he was able to take up the appointment. Based on his experience the previous year Eric McPherson went over as well, as the second rep. For 1949 George Morrison, from Ballarat also went over, but he went as a private, freelance rider. Before he set off Harry once again did well at the Australian GP at Mt. Panorama, winning both the Lightweight race, (on a Velocette), and the Junior, on a Manx Norton.

Both Harry and Eric did exceptionally well for newcomers in the Isle of Man TT races. Harry gained a ninth spot in the Senior, and a 15th in the Junior, with Eric managing a 14th and an 11th spot respectively. George also did very well indeed for a non-sponsored rider, getting a 31st and a 27th. Afterwards Harry and George travelled around Europe, entering several Grand Prix races and many minor ones, all as part of the ‘Continental Circus’, gaining a number of minor places in the process. Both learnt a considerable amount over those few months, but it was all worthwhile. All three Australians were offered rides on ‘works’ machines that year. For the Ulster GP over the Clady circuit, Harry was given a 350 Norton, George a spare 500, and Eric a 350 7R AJS. All three classes raced together. The 500s were first away, then sixty seconds later the 350s were sent off, with the 250s getting away another minute later. Eric on the 7R did exceptionally well to finish 4th .in the Junior; but Harry could only manage a 7th. Eric’s 7R had an oversized tank fitted, so he could ride the entire race without refuelling, but Harry’s machine was fitted with only a standard tank, but he had been consistently holding third spot until he had to call into the pits to re-fuel.

Bringing his Nortons back home, Harry entered the Australian TT, held that year at Noorioopta in South Australia, and won a great double in the Senior/Junior races, held on Boxing Day, and a few days later, on the 2nd January 1950, Harry won the Junior Victorian GP, and took out second place in the Senior, behind Tony McAlpine. Once more Harry was allocated a pair of new Manx Nortons for the 1950 European season, but was determined to make one last effort to win a Senior race at Bathurst prior to his departure for Europe. Riding his by-now ancient girder forked 250cc BSA Harry had to give best to Les Diener on his camshaft Velocette, to eventually take a second place in the Lightweight GP. When well in the lead in the Junior race, Harry had to pull into the pits to top up his oil tank and could only manage fifth spot. But in the Senior race Harry finally pulled it off. Starting from near the back of the field – positions on the start line were then drawn by ballot – Harry carved his way through the field, chasing down Laurie Hayes, who was riding one of Harry’s Nortons, and finally pulled away to win by around half a lap. The Senior race that year was started by the Managing Director of Nortons, C. Gilbert Smith, visiting Australia and New Zealand, and who must have been well satisfied to see one of his machines win. Immediately after the race Harry set sail to England for the TT races. This was the conventional way almost all Australians then went to England; even the Australian cricket team for the Ashes always went by boat, talking around six weeks for the voyage.

The three riders chosen to represent Australia that year were naturally Harry and Eric McPherson, and George Morrison was added to the duo as the third rep. In his first race in Europe, at the North West 200, held at Leinster, in May, Harry achieved a magnificent third place in the Senior race, behind Artie Bell and Johnnie Lockett, both full ‘works’ riders for the Norton company. George Morrison, showing his true value, was fourth. The Belgian Grand Prix followed, in early June, where Harry averaged 98.85 mph to finish in sixth place, behind the winner Umberto Massetti, on the brilliant new Gilera four cylinder. Then it was over to the Isle of Man for the TT races. The sensational newcomer, Geoff Duke, headed the works Norton team, together with Artie Bell, and Harry and George Morrison as the works second string. Eric McPherson joined the AJS works team, with Les Graham and Ted Frend. Nortons pulled off a ‘double’, winning both the Junior and Senior races, with Harry establishing himself as a world class rider with a pair of tenth places. Eric McPherson retired with clutch trouble in the Junior race, but covered himself with glory in the Senior. Riding a specially over-bored 7R, with a capacity of 358ccs, he managed a 14th place among the 500s. A truly great effort.

With these sort of results the three Australians secured their positions as full works riders, with all three going on to compete in most of the Grands Prix in Europe, though the works Nortons had a dreadful year most of the time. The Avon tyres they were using that year were not up to the task, with these problems most prevalent in the Senior races, where a combination of the improved quality petrol, the new ‘Featherbed’ frames, and vastly better engines all helped to outstrip the tyre technology of the time.

In the Junior race at the Dutch G.P. Harry brought his machine home to a creditable 6th position, and in the Senior scored his first podium place with a 3rd. All of the AJS and Norton works machines were put out in the Senior race when chunks of tyre tread began flying off. Harry out-braked Gilera works rider Carlo Bandolira on the last corner before the finishing straight, with two laps to go, and was able to pull away to secure a fine third place. That result, and 7th position in the Junior Swiss G.P, brought Harry once again a full works ride in the Ulster races in Ireland. Harry was back on a 350cc Norton, and found himself in a titanic struggle with Eric McPherson’s AJS 7R. Way out in front went works Velocette riders Bob Foster and Reg Armstrong, who between them skittled the lap record many times, but behind them were the two Australians fighting tooth and nail for that third spot. “McPherson and Hinton are so level in the struggle for third place that the timekeeper will not separate them. Then on the seventh lap a sheared clutch stud leaves McPherson with a locked transmission, and he slowly loses ground to Hinton – who, out to prove what he can do with a works model, is putting up a magnificent show.” is how the reporter for ‘The Motor Cycle’ saw the battle.

To round off an outstanding season Harry was also offered a works Norton for the final round of the year, the Italian Grand Prix. There Harry rode what is almost certainly his finest race ever. In company with World Champions Geoff Duke and Les Graham, Harry fought a race-long duel for the lead. For the entire race the three great riders were never more than a couple of yards apart, with the lead changing several times a lap. Each would hold it for a short while until the rider just behind in the slipstream would pull out and slip past – then it would happen again and again. Harry put up both the fastest and record laps for the race, and by the 20th lap was in the lead, and holding it. He was still there on the last lap, a bare yard in front of Duke, and another yard to Graham. But the skill and expertise of the World Champion showed through, and Duke pulled out of Harry’s slipstream fractionally before the last corner, to hold a one second advantage over the line. Les Graham, too, pulled the same trick, cracking over the line no more than a wheel width in front of Harry. As Harry ruefully admitted, “The buggers were just a bit too crafty for me that time.” It had been a terrific scrap, sealing beyond all doubt Harry Hinton’s future as a permanent works rider with the Norton company: great prospects were clearly seen for him.

Harry returned home with a brace of works Nortons, and immediately set about cleaning up the local scene. A first in the January Victorian GP, at Ballarat, was quickly followed by a ‘double’ at the Brisbane combined car and motor cycle carnival, held in March, where Harry won both the Junior and Senior races. Then the 1951 NSW Jubilee TT races at Mt. Panorama beckoned. After setting a new unofficial lap record in practice, at 3 minutes, 3 seconds, no less than three seconds under his own lap record, Harry was all set for the big weekend. Still riding his ancient 250cc BSA, Harry had to give best to a flying Sid Willis on the Velocette, but was able to hold onto his second place. On pole position for the Junior, Harry unusually got away to a rather poor start, holding a fifth spot on the opening lap, while Sid Willis flew into the lead. Then, a bizarre accident occurred. Following closely behind Bill Morris, on his AJS, Harry suddenly found a length of cable from a trackside loudspeaker whipped up from Morris’ bike, cutting his clutch cable, and giving him a severe cut across his chest. He battled on, eventually finishing in third position. But then in the Senior Harry took the lead on the third lap, and then went on to win with some five seconds over Jack Forrest, setting a new official, lap record in the process, equalling his practice time of 3 minutes, three seconds.

The final race of the day was the NSW Open TT, where the unlimited capacity rules allowed the big 1000cc Vincents to compete. Lloyd Hirst was the big danger, but when Lloyd went in to refuel Harry swept past into the lead, and was never headed. Harry also smashed the absolute lap record, in a time of 3 minutes, 1 second! So it was in a great frame of mind that Harry prepared for the Isle of Man TT races that year, this time having Tony McAlpine and Ken Kavanagh as fellow Reps.

That subsequent crash took him the whole year to recover from his injuries. Harry spent almost two months in Noble’s hospital before being allowed to leave. With their constant daily care and rehabilitation, Harry slowly began to get feeling back into his hand and arm, and when he was discharged he carried a little hard rubber ball, with which he exercised his left hand, slowly getting strength back into it. By this stage Harry was 41 years old – but he felt still quite capable of winning. There was no thought of giving up.

He kept in regular contact with the Norton factory, who were staunchly supportive. In recognition of his efforts, in 1952 they sent over to him the Junior works Norton ridden by Ken Kavanagh in the Isle of Man TT, making Harry even more determined to race at least once more at his favourite circuit – Mt. Panorama. At the medical he brusquely told the doctor he was fit and capable, and “the bugger should just sign the certificate and be done with it”. He did!

As the field lined up for the start of the NSW Junior TT a terrific rain storm swept over the course, making the wet roads treacherous for racing, and the pace eased slightly. But Harry, despite the appalling weather, began to find his pace, and slowly caught up with Allan Boyle’s Velocette, outbraking him to take second place with just three laps to go. He then had Jack Forrest in his sights. On the last lap down Conrod Harry was in Forrest’s slipstream, and pulled out just before the last corner, Murrays, to squeeze inside Forrest, and win by half a machine’s length. It had been an amazing display, proving to everyone the ‘Old Master’ was back – with a vengeance.

In a move which was seen by some as not in the best interests of motor cycle sport, the organizers changed the rules for the Senior race, making it open to machines of Unlimited capacity – which allowed the big Vincents in. Sure enough, Jack Forrest on his big black vee twin easily went past Harry on the first lap to take the lead. After Forrest crashed his big Vincent at Quarry Bend early in the Open/Senior race, Harry took the lead, a place he never relinquished. By 1953 Harry had a pair of genuine ex-works machines to race, and showed he had lost none of his ability and sheer determination, despite being the healthy age of 43 – when most riders had long retired. That year, the experienced New Zealander Rod Coleman was invited over for Bathurst. He was one of the works AJS riders, and was expected to give Harry a real run for his money, having finished a fine 4th in the 1952 Isle of Man Senior TT. For the Lightweight race Harry had meticulously prepared a sleeved down 350 Manx Norton, on which he won handsomely. In the Senior Harry soon found he had a real fight on his hands. Maurice Quincey, half Harry’s age, shot into the lead, followed by Rod Coleman, with Quincey setting a new lap record of 2 minutes, 58 seconds. But Harry was not done yet. Reeling off two laps at 2 minutes, 57 seconds, a new record, Harry firstly got past Coleman, then slowly narrowed the distance between himself and Quincey. On the penultimate lap Harry excelled himself, lapping in 2 minutes, 53.5 seconds, to sit right on Quincey’s rear wheel as the pair shot down Conrod. Once again Harry out-braked his younger opponent on that last corner, went inside, and took the flag. Was there nothing the veteran Norton rider could not achieve? Well, the Junior race was to follow.

At the start Coleman, from way back in the grid, shot into the lead, opening up a large gap. Quincey and Bob Brown were fighting for second place – but once more the veteran was flying. Halfway through the race he equalled the old Senior lap record to take second, and then slowly but surely wore down Coleman. On the last lap Harry set an unbelievable new Junior record lap in 2 minutes, 58 seconds to majestically sweep past Coleman to take the lead, and went on to win. Harry, rather modestly, simply said he had everything going for him that day. But he admitted that toward the end of a race he barely had the strength to fully pull in the clutch lever when changing gear. He found, though, that by just partly pulling in the clutch lever, he could make gear changes fractionally faster, not even having to ease the throttle! Once Harry discovered this, he went on to use this technique for the whole of the race – and taught the method to his sons. It required finesse and timing – but Harry had that in spades.

That left the one big race, the Unlimited TT, run on Easter Monday. Apart from the 500s entered there were also eight 350s, plus a handful or so of the big Vincents. The big question was: could Harry make it four out of four? Early in the race Harry took over the lead and was never headed, lapping easily around the 2 minutes, 57 seconds mark, well ahead of Rod Coleman. For any rider to have recovered from a serious crash only a couple of years before, and to have only one eye, to simply race again would have been a significant achievement: but Harry took things to a level no-one could have expected.

In practice at Mt. Panorama in 1954, on his Senior Norton, a bolt came loose as Harry was racing over the top of the circuit, locking the back brake and causing him to crash heavily. At hospital, the doctors discovered Harry had broken three ribs and his collarbone. The accident put him out of racing for the whole year. This time, surely, Harry would call it quits. But Harry was not ready, just yet, to hang up his boots. He entered for the 1955 NSW TT at Mt. Panorama, announcing that he would be retiring afterwards. But if anyone thought Harry would be content to just race around on his swansong they were to be savagely proven wrong. In a glittering finale Harry, showing he had lost none of his fighting spirit and utter determination, beat his old adversary Rod Coleman in both the Senior and Junior TTs, to win a magnificent final ‘double’.

At the presentation it is doubtful if any of the thousands who had crowded in to see the races went home early. The area in front of the grandstand was packed to bursting point, and when Harry stepped up to receive his awards, the applause simply went on and on. It was a very historic moment. The end of a magnificent era, one that would always be remembered for those lucky enough to have been there.

Australian motorcycle racing and the name of Harry Hinton will always be linked indelibly. Harry went on to advise, help and be mechanic to his sons for several years, always retaining his close interest in motor cycle sport. Harry passed away in 1978, aged 67 years . . . and we lost a remarkable man.

Author’s note

I would like to thank most sincerely the members of the Hinton family who spent many hours patiently talking and reminiscing into a tape recorder, over many weeks, which provided the core material for this article. As always, any mistakes or errors of fact are mine alone. The original tapes are now stored in the National Library, Canberra.