George Begg has never been shackled by tradition. A self-made successful businessman in his native New Zealand, he has used his affluence to indulge in the things he loves; motorcycles, racing cars, travelling and writing, and in a 40-year philanthropic career that has seen him at the helm of fund raising ventures that have continuously benefited the less fortunate.

Although he is one of his country’s most successful racing car constructors, George is at pains to point out that motorcycles are his first love. “I just love the people (associated with bikes). There was no one-upmanship and there were no superstars who wiped their boots on everyone else. Friendship abounded. They were marvellous guys.” He’s well qualified to make such a statement. Since his motorcycling days began in 19498, George has met literally thousands of fellow motorcyclists, from the down-and-out clubmen to world champions – and to the true extroverts like Burt (World’s Fastest Indian) Munro. Munro’s devilish cunning, his ability to charm and beguile his way around the world and into the hearts and hip-pockets of scores of people, inspired George to write the book, Burt Munro. Indian Legend of Speed, which paints a rather more warts-and-all picture of the old rascal than did the film starring Sir Anthony Hopkins.

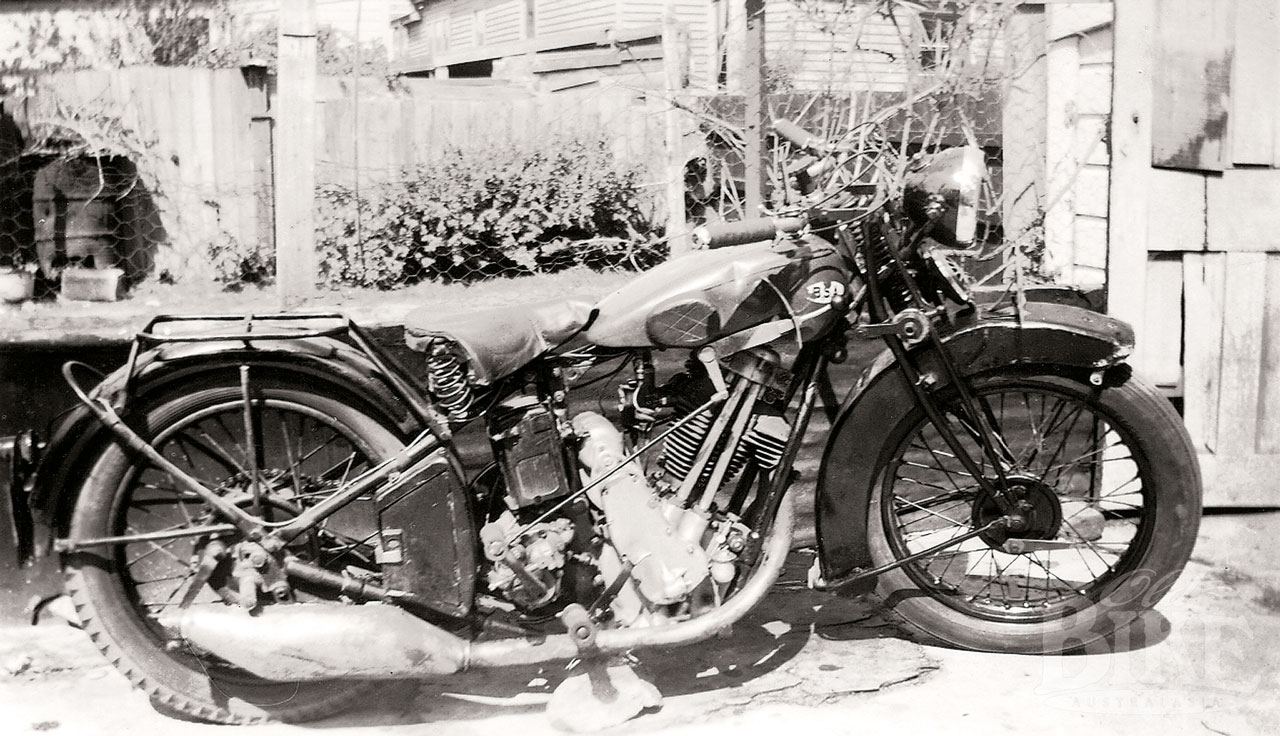

Raised on the family farm in the Southland region of New Zealand’s south island, young Begg was trained as a fitter and turner in Dunedin, and bought his first motorcycle, a 1929 BSA Sloper, from his elder brother George in 1948. “In reality it was a pig of a machine with few redeeming features, but to an 18-year-old, it was marvellous. On the ancient single, George covered many miles around the craggy coast of Otago Harbour and soon caught the racing bug, joined the Otago Motorcycle Club, and obtained a 1938 500cc Royal Enfield Silver Bullet. He formed a friendship with another Enfield owner, Doug Johnston, and the pair raced when and wherever they could in their region, and even travelled to Auckland at Christmas in 1951 to watch the New Zealand Grand Prix – the big time – at Mangere.

Gradually the Enfield was tuned and fiddled to the point that it was no longer usable on the street, so a 650cc BSA Gold Flash outfit was added as road transport. Later he and Doug Johnston bought a GP Triumph and an ex-Len Perry 1939 KTT Velocette between them, and began plying the tracks on the north island. Basing themselves at Taumarunui, the lads managed starts at Matarawa near Wanganui, at the Waitara circuit in Taranaki, and at the King Country GP at Taumarunui itself. The troublesome Triumph was replaced by a Manx Norton purchased from Rod Coleman, but the twosome went separate ways soon after and George purchased Johnson’s shares in the bikes and returned to Winton in Southland. Working in a local garage, he kept his hand in on the KTT at Oreti Beach for racing and record attempts. But bigger plans were hatching.

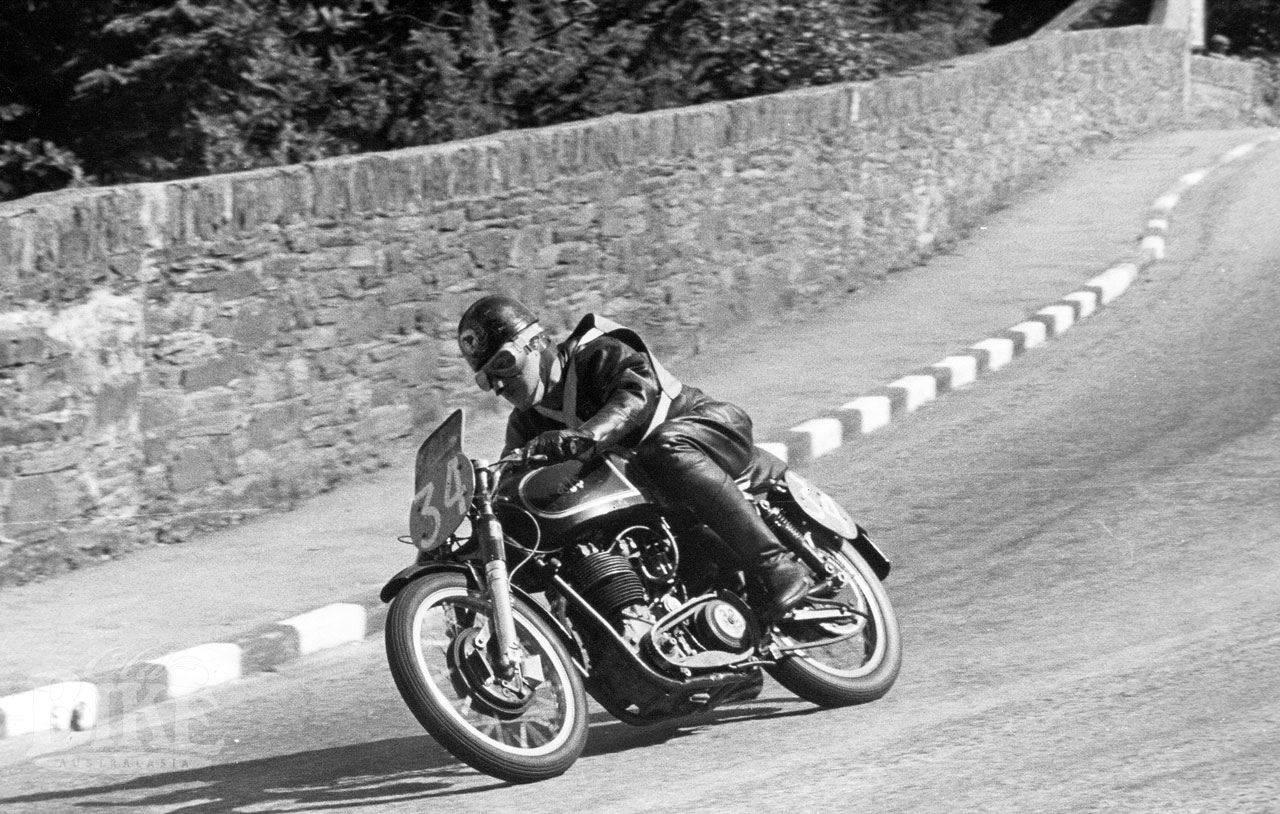

Early in 1955, George and his mate Bob Cook took jobs as engineers in Kawerau, helping to install a paper machine and earning big money. As soon as they had their fares saved, the pair boarded the Rangitiki in Auckland and sailed for England, in June with the aim of competing at the Manx Grand Prix on the Isle of Man in September. One of the first stops was to the AJS works at Plumstead Road in London where George shelled out £336 ($672) and wheeled away a brand new 350cc 7R AJS. Cook purchased a similar, second-hand model in Manchester and the pair headed for the island. Their digs in Douglas was at the Rose Villa, the spiritual home of Anzac racers, run by Roy and Gladys Gilbert. Although Cook’s 7R broke down in both the Junior and Senior Manx GPs, Begg rode steadily to 22nd in the Junior and 25th in the Senior, collecting two bronze finisher’s medallions. A few races on the English mainland followed before winter set in and the pair found jobs on the production line at English Electric in Liverpool.

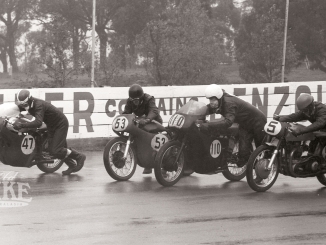

The 1956 racing season kicked off in April at Silverstone, where Bob Cook showed that he was rapidly maturing as a rider. This was followed by meetings on the Easter weekend at Brands Hatch and Oulton Park, before the pair sailed for Ireland and the North West 200. The pangs of homesickness abated somewhat with the large number of New Zealand and Australian riders present, but it was to be a sad occasion when Bill Aislabie, from Palmerston North, was killed in the 350 race.

Back in the Isle of Man for the 1956 TT races, the two Kiwis found themselves surrounded with Down Under pals at the Rose Villa. Ensconced there were Bob Brown, Allen Burt and Geoff Coombs from Sydney, plus a large number of Canadians. Burt unfortunately crashed heavily in practice and put himself into Douglas hospital for six months. Begg again finished both Junior and Senior races, while Cook came home a fine 25th in the Junior for a sliver replica. More importantly, George struck up a friendship with a local lass, Freda, who would become Mrs Begg later that year.

With their ambition of competing in the TT accomplished, George and Bob began to make plans to return home, but there was the major part of the UK season still ahead of them. In late July, they were at Aintree, near their UK base at Liverpool, for a national meeting. Just two laps into the 350cc practice session, Cook crashed into a concrete wall and never regained consciousness, passing away the same evening. After competing in the Ulster GP, for which he and Cook had already paid their entry fees, George sold his 7R and hung up his helmet. After his wedding to Freda in December, he found work in the Rolls Royce plant on the Isle of Man, and the pair sailed for New Zealand in April 1957.

George’s passion for motorcycles had been extinguished, at least temporarily, and with only $100 to his name, he rejoined the workforce for a heavy engineering firm, working on excavators on frozen, mud clogged sites through a particularly savage winter. The experience was enough to convince him there had to be a better way to earn a living, and with a little financial help from his father, he bought a welder and some other basic equipment and set up a general engineering business working from a tiny shed on the family farm at Drummond.

Business was slow to begin with, but one day a discussion with a sheep farmer changed everything. The rural Southland region at this time was in the grip of an epidemic of footrot, which meant that at least twice per year, each animal had to be captured, and tipped upside down (an exhausting, back-breaking process) to have its feet treated. Begg devised a gadget to hold and invert the sheep, built a prototype, and demonstrated it to an appreciated audience. “I couldn’t build enough. Within a year, mu business had grown so much that I was building a factory on land I had bought in Drummond. There was too much work for one man…In one year alone, we built more than 700 of the ‘handlers’.” Within six years, the invention of a footrot vaccine stopped demand for the handler dead, but George had seen the writing on the wall and diversified into other farming accessories – front end loaders, ditch cleaners, and the business boomed. Bigger factories, a bigger house, and a few of the finer things in life.

The new degree of comfort also allowed George to seek a leisure time activity, something he had never had time for until now. He began reading up on racing car design, which was going through something of a revolution in the early to mid 1960s. In the little workshop he called The Toy Show, George worked out the design and engineering of a single seat racing car powered by a 650cc BSA twin. The first Begg car was hardly finished before George was sketching the next. This one had a 1600cc Hillman Super Minx engine, mated to a DKW gearbox, proved quite successful at tracks like Wigram Airfield, Teretonga and Ruapuna. Both cars were sold and a third, a 283ci Chev V8 engined sports car, quickly took shape. It had become standard practice to test the cars on ‘Drummond Straight”, a two-kilometre section of public road outside the factory, where about 225 km/h could be reached – provided The Law stayed away.

Until 1976, Begg and small team of helpers churned out no less than 18 separate cars; everything from Formula 5000 open wheelers to twin cam F2-style cars, plus a McLaren-based sports car that became known as the McBegg.

The reason it came into existence is the result of a meeting with Bruce McLaren, who had successfully amalgamated driving and construction. The conversation at Wigram lead to the offer of a six month stint in at McLaren’s factory at Colnbrook in England, and within weeks the Begg family was packed an on its way. George was officially employed on the construction team, but in reality everyone mucked in to get the job done against crazy deadlines, building and preparing Formula One and Can Am sports cars.

When the Beggs left for home, packed in the expansive crate was a McLaren Can Am chassis circa 1965, together with bodywork from an M6. The McBegg, with its 5.9 litre engine, was quite a weapon in New Zealand, ranged against Elfin 400s and the earlier Begg Chev.

In 1973, Begg even took his Formula 5000 car, the FM5, to Britain and Europe for a season, with David Oxton as driver. Despite a massive accident at Brands Hatch, the tiny team about broke even, and George more than justified the trip by buying a quantity of machinery for the factories back home, “at a keen price.” By the time the period as a constructor and entrant was over at the end of 1976, George had not only built 18 of his own cars, but owned an ex-Formula One TS9B Surtees and a Formula Two McLaren M4B. Both were soon sold however, and once again George faced a hiatus period in his ‘leisure time’.

What now? Golf, fishing, bowls? No, it was back to motorcycling. In the time George had been away, the enjoyment and racing of historic motorcycles had snowballed world-wide. George’s re-introduction to bikes happen when he was invited to the inaugural meeting of the NZ Classic Racing Register at Pukekohe in 1979, There he met lots of old chums and an upshot was the formation of a South Island branch of the Register, with George and Maurice Wear as the driving forces.

Race meetings at the little Timaru circuit near Christchurch followed, but the club hit a major milestone when it organised a return to the historic Cust circuit – the site of the original New Zealand Grand Prix in 1936. A small faming community 70 km west of Christchurch, the 10km roughly rectangular circuit featured sunken bridges, rocks, choking dust – the usual mixture for an Antipodean Grand Prix of the day. Organising the meeting was no small affair, with a multitude of tasks involving closing and securing the public roads, to be undertaken. But it went off extremely well, with 80 riders entertaining the crowd on day that the Cust community still talk about. Despite the success of the Cust Revival, the club reckoned it could only cope with one meeting every three years. The event ran until 1999, during which time George managed to get himself highly involved in classic motorcycle racing.

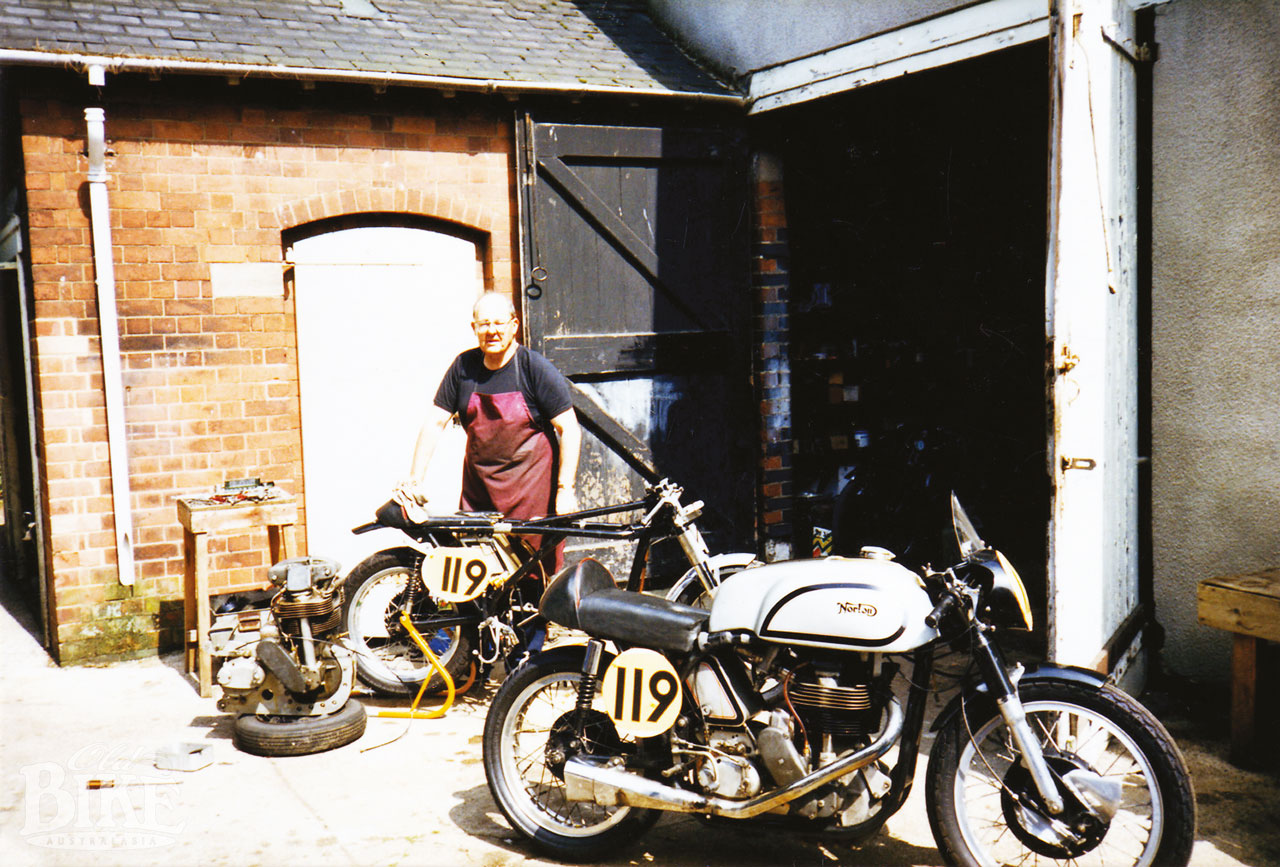

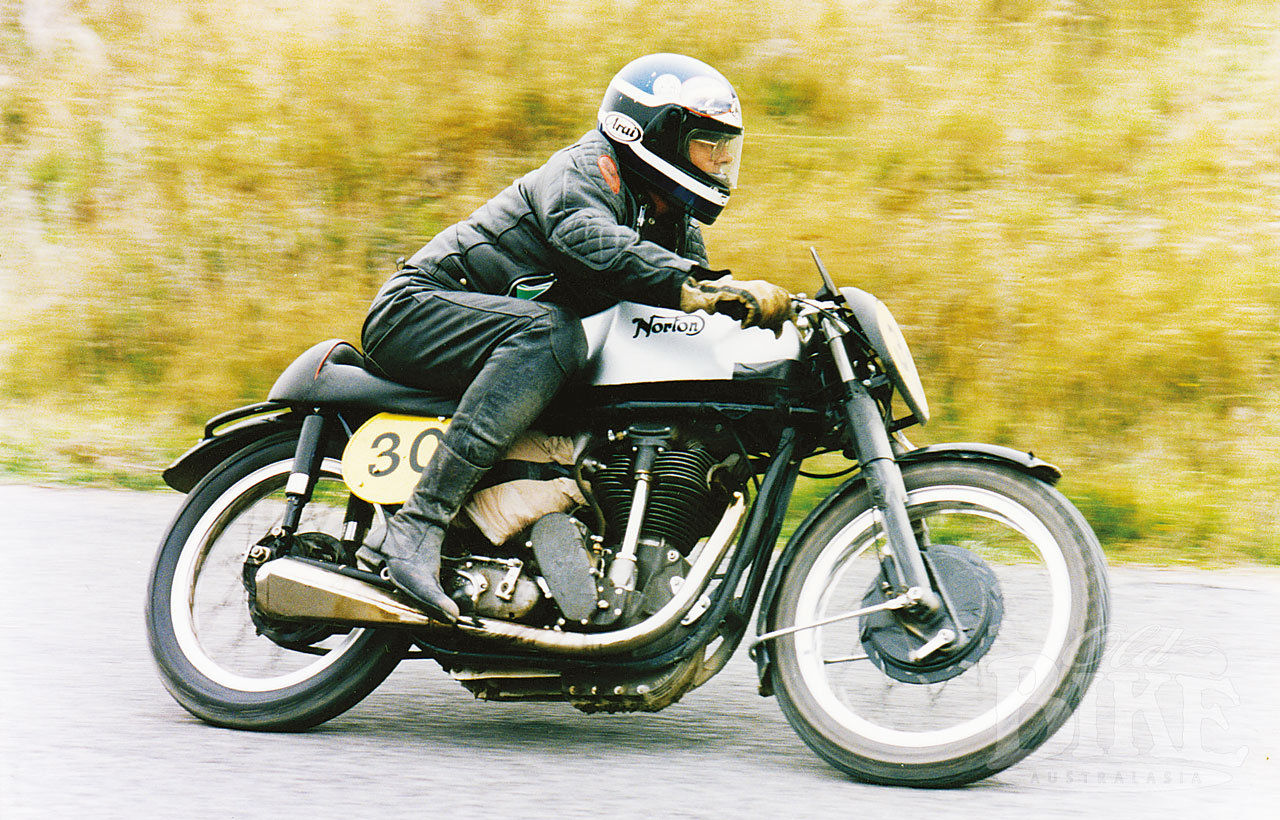

With four-times World Champion Hugh Anderson, George set off for the Isle of Man in 1985, forty years after he had first set foot there with his 7R. This time he had a 500cc long-stroke 1952 Manx Norton, and his aim was to ride in the Manx Senior Classic Race. Prior to the event a later short stroke Manx was procured, but this seized halfway through the 3-lap race. The Norton was rebuilt in time for the Old Timers Grand Prix at Salzburg in Austria, and the fuse was well and truly alight. A return bout was organised for 1987, when George and the rebuilt Manx took in the Classic Dutch TT at Assen as well as several British races.

Back home again, George contemplated a final fling for 1988, when he would be better equipped. He had long had theories about motorcycle frame design, and decided to exercise these on a new chassis for the short-stroke Manx engine. Rather than a full-cradle design, the Begg frame stops the front down tubes at mid crankcase height. The engine/gearbox unit are encased in full-circle aluminium plates, with the motor further forward than standard. One advantages was that the engine/gearbox unit could be removed in under 20 minutes. This machine, together with a standard Manx, was loaded onto a trailer, shoved into a container and shipped to UK. At the Classic Manx, 58-year old George and his Norton-engined self-creation completed the four laps without incident. “I was never in the winning class, but I didn’t disgrace myself either.”

Later the Manx engine was replaced with a Matchless G50. This George basically machined himself from castings procured in Australia. By now he had set up home at Hervey Bay, Queensland, where he quickly became involved in numerous community-based and charity projects. He rode it at the 1999 Cust Revival and still owns the unique special.

In between raising a family of four, running a successful business, organising race meetings and building racing cars and motorcycles, George has been a staunch worker for charity for decades. He helped to raise $640,000 for a Cot Death Fellowship appeal, and in his spare time has managed to write four books.

George Begg has spent a lifetime immersed in motor sport of some kind or other, and maintains a boyish excitement for any branch of the sport. In November 2006 he watched as one of his Begg FM18s perform in front of an appreciative crowd at the Tasman Series Revival at Sydney’s Eastern Creek. Although not in the best of health these days, George’s bubbling enthusiasm, can-do outlook and steel-trap mind are still an engaging combination.

From the editor: Shortly after this story was written, George Begg passed away. He had been bravely battling cancer for more than a year, and it seemed at one stage that the treatment was having a positive effect. However in April 2007, George lost the battle. I have left the story exactly as I wrote it, because George’s influence will be with us for a long tome yet. – Jim Scaysbrook

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: George Begg archives.