Few people have ridden overland from India to England. Even fewer would still own the bike they rode, 58 years after the ride, and still use it regularly. Such a man is Doug Voss, 85 years young, from Adelaide.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Rob Lewis and Voss archives

“I never throw anything out,” says Doug, and we’re richer for it. He still has the first motorcycle he ever owned, a 1926 500 cc G10 AJS that he bought for £25 as a 17- year-old, and which had served its early years on the speedway in the hands of the pioneer American star Lloyd ‘Sprouts’ Elder. Aboard the AJS, Elder spent the 1927/28 season racing at The Speedway Royale at Wayville Showgrounds. It has been recorded that Elder won the Australian Championship in 1927, but this is not verified by historian Jim Shepherd, who states that Elder finished third in the 1927 title held at Hamilton, NSW. Whatever the true story may be, the G10 AJS, big brother to the highly successful 350 cc G7, remained in South Australia and was purchased by young Doug to use as everyday transport. With no kickstarter it was a bit of a chore around town, but at least it had been fitted with a 3-speed Sturmey Archer gearbox, and did sterling service for a number of years before being confined to the shed.

Its replacement was another AJS, a 1936 500 cc Model 18, which Doug says he was initially attracted to because of its ‘gorgeous upswept exhaust pipe’. This was a slightly more practical machine that really earned its keep. “I literally wore that bike out,” says Doug. “Everything was worn out, the fork bushes, the gearbox, the engine, everything.” Once again, the AJS went to the shed to keep its elder sibling company, and this time its replacement was a utilitarian Royal Enfield Model J, a 1949 model purchased in 1951 from Laurie Boulter. “A bit boring,” is how Doug describes the Enfield, but that is possibly a little unkind for a machine that has taken him halfway around the world.

Doug had always been a keen and talented amateur photographer, and in the days when the Box Brownie was about the best most people could aspire to, he owned a nice German Kodak Duo 620 camera with a good lens. Naturally he still has it, along with a carefully catalogued collection of negatives that record the action of local race circuits like Woodford, Gawler and Nuriootpa. But by 1951 he had the wanderlust. “I read a book called Dust on my Shoes by Peter Pinney which was very interesting but ended up rather tragically, and then I heard about a couple of fellows who tried to ride a Velo from India to England, two-up. The Velo fell apart apparently, but the idea interested me, so I bought the Royal Enfield and a Hawk sidecar chassis and built a box for the chassis. I had been in the Air Force during the war, and I thought I’d try riding to London, so I got a strip map from the Royal Automobile Club in London, all set out, incredible – the entire route.”

To prepare himself for the massive trek, Doug decided on a preliminary run in Australia, which he undertook in late 1951. The trip took him from Adelaide to Port Augusta, Broken Hill, into Queensland then down the coast through Sydney and Melbourne and back to Adelaide. It was accomplished without major incident and Doug felt he was now ready to tackle something much more challenging.

“While I was preparing to leave for India, the government of Iran nationalised the BP Oil Refinery in Abadan so the British government discontinued diplomatic relations with Iran, and I was on a British passport then, so Iran was out. So I shipped the bike to Bombay, then transhipped it on a local cargo ship to Basrah and started off from there. My timing was not very good because they were having one of their worst heat waves in years when I arrived there in July– over fifty degrees, week after week.” After reaching Baghdad, Doug set out west across Iraq into Jordan and on to Damascus. “I carried a four-gallon drum of petrol and a four-gallon drum of water. I had no weapon, just a knife and fork, plus I was six foot four. I honestly think I would have had more trouble if I was armed.”

Basrah brought a dose of reality, as Doug explains. “Shortly after arriving at Basrah, while preparing the Royal Enfield in a hangar at the airport, I was approached by a Mr Marshall, the British Consular Representative in Basrah, who informed me that he had booked return passage for me and my bike to Bombay on the next coastal steamer, because in his opinion the Enfield was ‘undesertworthy’ He cited the recent example of some people in a Standard Vanguard that had failed to make the journey, and he reasoned that I would have even less chance on a motorcycle.” Thanking Mr Marshall for his advice, Doug declined the offer and prepared to set out.

The first setback occurred on the first day out of Basrah. “With a strip map, you needed a speedometer, but with the rough roads and the vibration, the speedo on the Enfield fell to pieces after about 50 miles. In the extreme heat, bouncing along broke the footrests off, so I had to get that fixed. Royal Enfields have a cush rear hub, and sand got in there, locked it solid, and the chain pulled the brake off the sprocket band near a place called Kut in Iraq. I managed to get the bike into the town and there was a shed with a big six-cylinder side-valve car engine driving belts and things, and amongst other things there was a generator for an arc welder – I’d never arc welded in my life – and a hand-cranked grind stone. It took ages to un-seize the hub because it was jammed solid, and I had a go at welding it myself. They had one size welding rod, about as thick as a pencil and I didn’t know what I was doing and the rod kept sticking and almost stalling the engine, but eventually I got it stuck on with all sorts of lumps sticking out that I had to grind off on the stone, and got it all back together and set off again. “

Approaching the village of Amara, the local children all came out to greet the tall stranger on his motorcycle, but so did a soldier, who beckoned him to stop, which he did. The soldier indicated that Doug should pull off the road, and he indicated a house surrounded by trees. “He actually stopped me because it was too hot to ride,” Doug recalls, “and the house that he pointed to was operating as a hospital for leprosy sufferers. I knocked on the door and a European man answered. I said to him, ‘Hello, my name is Voss and I am from Australia’, and he answered, ‘Hello, my name is Voss and I am from America!’ By this stage I was not feeling too well and he diagnosed that I had the early stages of dysentery, which got progressively worse and I spent a week recovering at the hospital.”

“I was told to keep off the road which was too rough, and to travel on the desert. As long as you’ve got the Tigris River on your left you can’t get lost, they said. After a while I couldn’t see the Tigris River at all, but I kept going.” Continuing to avoid the pot-holed roads and stick to the sandy desert made progress slow, and Doug recalls encountering a sand dune that was too big for the heavily-laden outfit to cross. The only solution was to unload the contents of the box and what was being carried on the bike, carry it all over the dune, then return and walk the outfit over. Wheel-spinning through the deep sand clogged the air filter (which faced downwards towards the rear wheel) and allowed the desert to be ingested into the engine. As the motor munched away on its abrasive diet, the throttle slide jammed open, so the only way to slow down from here on was to retard the spark. “I eventually got to Baghdad and pulled it all down and had to get the engine re-sleeved. I found a place that was just a hole in the wall but they had a lathe and I had a spare set of rings with me. They made a new sleeve and I used the same piston with new rings so I was mobile again. The only thing they forgot was to put an oil-way at the base of the barrel, but I got hold of a drill and did that myself.”

Setting out from Baghdad with 1000 kilometres of desert between him and Jordan, Doug only reached Fallujah before being stopped by army personnel, who warned of the perils of travelling under the blistering sun by day. They advised that the best way to traverse the Syrian Desert was to follow the Nairn buses, which operated at night. This business had been set up by the Nairn brothers (former motorcycle dealers in New Zealand before WW1) initially using Cadillac cars to carry mail. The passenger buses operated at high speed and stopped for no-one, particularly the bandits that inhabited the region. In the cool of the evening, Doug set off, glued to the back of the bus, but the Enfield simply wasn’t up to the task and the vehicle was soon just a speck in the distance. Fortunately, the army had radioed ahead to Rutbah, roughly half way, and when Doug finally hove into view his arrival was expected.

With the worst of the terrain behind him and the Enfield running satisfactorily on its new innards, Damascus was reached without further incident, although he ran foul of the Syrian authorities for overstaying his visa by one day. With that sorted out, he pushed on to Turkey, Greece and Yugoslavia. It was in the latter country, at that stage a series of constantly warring states, that Doug met up with an Austrian tourist, Rolf Ebner, who was riding a 250 cc Puch two stroke. The little Puch was considerably faster than the Enfield, but Doug did his best to hold onto his new chum as he had little idea of the route. “We came to a border crossing and Rolf got through just as they were lowering the boom, “ Doug explains. “ I didn’t want to lose track of him so I just dodged around the barrier and kept going. They didn’t like that at all and came after me and caught me and locked me up. I was interrogated by a woman of about my size for six hours as to why I had run through the checkpoint and I just stuck to my story that I didn’t want to lose track of Rolf as I had no map. I don’t think she believed me but eventually told me that I had better leave Yugoslavia, which was fine with me.”

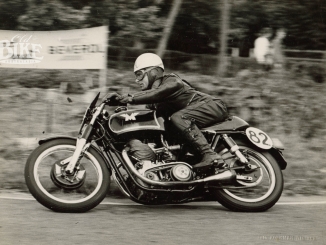

Next destination was Italy, and here it was time for a little rest and recuperation. The Italian Grands Prix, for motorcycles and cars (held at week apart) was on at Monza and Doug took his place amongst the spectators at the spectacular circuit. Several Australians, notably Sid Willis, Tony McAlpine and Gordon Laing, were competing. From Milan it was a comparatively easy ride to the channel and finally to England. “In London I got a job in a tea shop in Lyons, and not only did it pay six pounds a week, you got three meals a day, six days a week. In November I decided to go to the Earls Court Motorcycle Show, so I rode the Enfield and parked it outside. I bought a ticket and went to the Royal Enfield stand where I told them that I had come from Australia on a Royal Enfield, which was parked outside, and perhaps they might be interested in displaying the bike on their stand. They came outside and looked at the bike and said, “This model is four years old and out of production. We now have the new Bullet, thank you” and just turned and went back inside!” It says something about the attitude and marketing skills of the British motorcycle industry at the time.

“Being young and a bit stupid, I had a secondary plan to come back through Africa. I went to the French Embassy to get a visa for Algeria, but they refused to give me one. The reason was that shortly before I came in with my request a Canadian called Spike Rhiando decided to cross the Sahara on a scooter, an elaborate scooter with a two-way radio, but he didn’t make it, and it cost the French government a lot of money for the Foreign legion to try to find him, which they did in the end, so they said ‘That’s it, no more adventurers on bikes’. So I battled with the French for a while, wrote to Algiers and so on, but in the meantime I met this Australian girl and lost interest in the whole thing. We got married in London and shipped the Royal Enfield back.”

The gallant old Enfield had earned a rest, so Doug treated himself to a Vincent HRD Rapide, and for once he broke his golden rule. “As I have said, I never throw anything away, but I am afraid the Vincent eventually had to go in order to carpet the new house my wife and I had bought in Adelaide. At least we still have the same carpet, 53 years later.” And he still has the Royal Enfield, which was refurbished a few years back, but still runs the sleeve that was turned up at the hole in the wall in Baghdad. The box was removed (but not discarded) and replaced with a Goulding sidecar, and the bike is still road registered and still used. “A group of us used to go riding every week,” Doug says, “ but now we just go each month.” Until two years ago, he regularly rode a Suzuki GSX 1100, but that has now been retired to the back of the garage, along with the two AJSs, both also restored.

So next time you saddle up for a ride in your waterproofed jacket and boots, full face helmet and warm gloves, with your GPS navigation system and mobile phone, cast your mind back to a simpler era when all Doug took overland to England was a knife and fork.