Circuits come and go. Some are revered, others quickly forgotten. Catalina Park, in a dreary gully at Katoomba in the NSW Blue Mountains, is an example of the latter. A more hazardous concoction of made-for-racing roads would be difficult to imagine, and the circuit claimed the lives of three cars drivers in rapid succession in the late 1960s.

It was officially known as Walford Park, unofficially known as The Gully, and renamed Catalina Park after the derelict aeroplane that floated for a while in the artificial lake at the entrance to the track.

The idea of construction a track in what the locals referred to as The Gully was first mooted as early as 1953, when members of the Blue Mountains Sporting Car Club began discussions with the local council. The plan was to convert a controversial Aboriginal camp into a leisure park incorporating a 2.4 kilometer racing circuit, but it was not only the terrain that proved tough going.

According to ABC reporter Martin Thomas, “some of the town’s poorer citizens, many of Dharuk and Gundagarra descent, were evicted from their homes in order to make way for a racetrack. The Catalina Park racing circuit was in trouble from the start dogged by bad weather, financial insecurity and, some might say, ‘bad karma’. Forty years on, it remains a site of tension in this small community: the centrepiece of a story encompassing memory, forgetfulness, the machinations of local council and enduring dreams of the tourist dollar. “

In “A Heritage Study of the Gully Aboriginal Place, Katoomba NSW. Prepared for Blue Mountains City Council 2005,” the saga of the resumption of the land was similarly apologetic. “…the inhabitants “were accepted as individuals, but their status as outsiders remained, and when it became possible for the respectable citizens of the town (of Katoomba) to remove the camp by building the Catalina Racing Circuit in the late 1950s, the opportunity was taken and this small community was destroyed.” “More than just an aboriginal place, this location also has significance for the descendents of the non-aboriginal families who lived side-by-side with the Aboriginal people, sharing their struggle, often assisting with food and friendship when times were tough. “Despite the near total devastation that resulted from the construction of the racing circuit, meagre traces of the fringe camp and scattered stone artefacts remain”.

Much of the track remains too, and although now closed to vehicular traffic nowadays, it can still be walked, or cycled around.

Mist on the Mountain

With the closure of Mount Druitt in late 1958, The Australian Racing Drivers Club began to take a renewed interest in the Catalina Park project, which had trundled along at a snail’s pace for years. Constructed had been hampered as much by a lack of funds and personnel as the weather – a factor that was to plague the facility for its entire existence in motor sport terms. The addition of ARDC manpower saw the circuit quickly come to fruition, although the original opening date in 1960 came and went in silence. It finally opened in February 1962, the same month as the new circuit at Oran Park.

An inspection by the Auto Cycle Union produced a report of cautious praise. From a motorcycle racing perspective, Catalina Park represented everything that a circuit should not. The inside of the circuit presented sheer drops to the valley floor, while the outside extremities were lined with old railway sleepers, right to the edge of the bitumen, held in place by vertical posts that protruded above the top rail. In reality, there was very little space available, so the track’s shape was largely determined by the geography.

From the downhill starting line on what was officially known as KLG Straight, the circuit bottomed out through a gradual right hander leading to the hairpin Dunlop Corner. Then it was quite a climb, hugging the mountainside all the way, to another hairpin, Craven A. Next came the most daunting part – the plunge through a left/right king down towards the pit area and through a very quick right hander (Bosch Corner) at the base of the hill, before disappearing into Energol, or the Tunnel of Love as it was more commonly named. It was a lap of almost exactly two kilometres – the only relatively flat section being the approach to Dunlop Corner known as Neptune Straight.

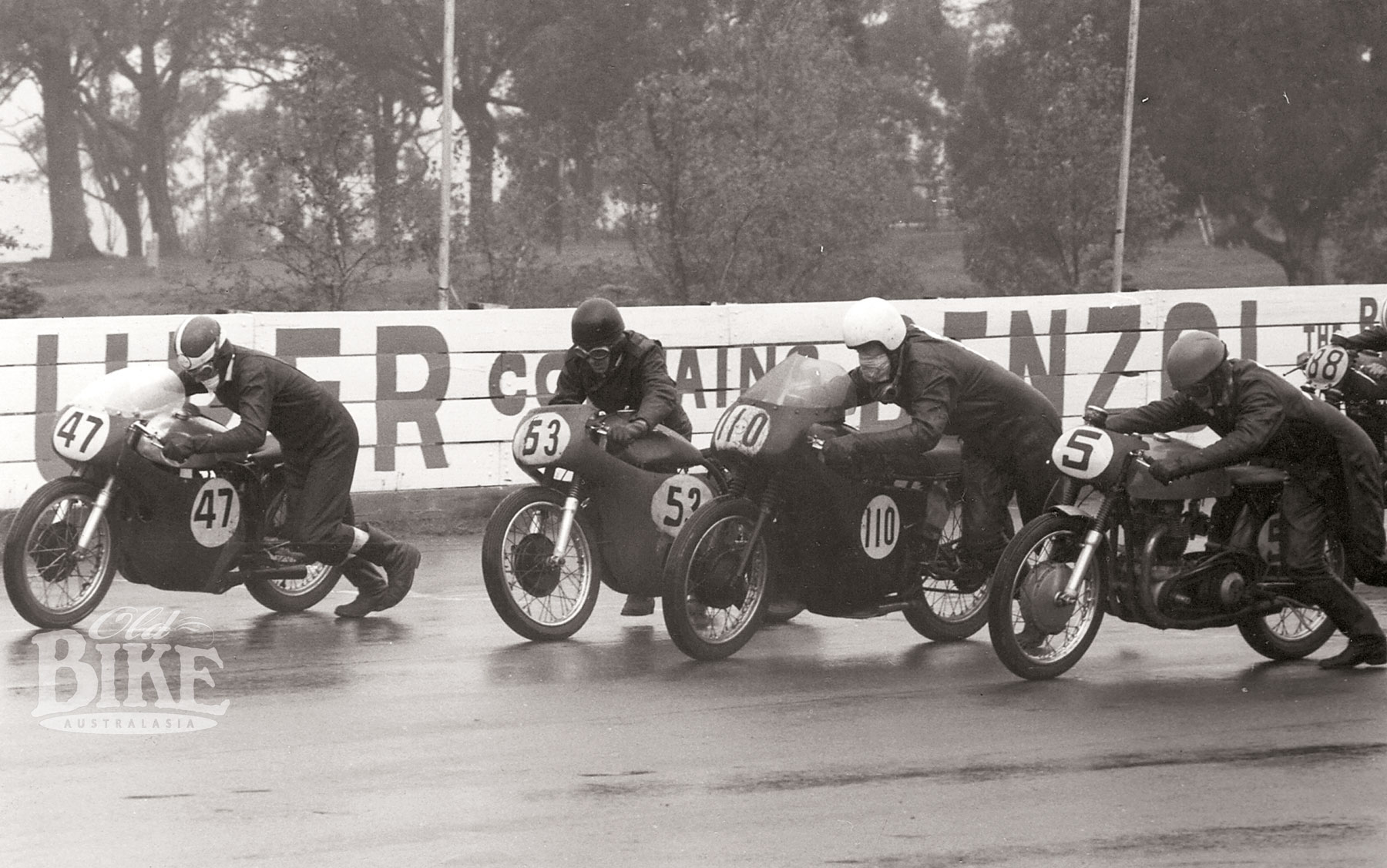

The cars had been at Catalina for three years, suffering perennial fog-bound delays at most meetings, before the bikes arrived on November 28, 1965. Practice was held in bright sunshine, but come race day, it was pea soup as usual.

A surprisingly good entry made the trip into the mountains. After years of totally dominating the local scene, Kel Carruthers was preparing to head overseas and did not enter. Another rider with his bags packed for the 1966 European season was John Dodds, but he had a quick Cotton Telstar at his disposal and reckoned it would be ideally suited to the ultra-tight Catalina layout.

Once the mist had cleared, racing got under way with a packed program that even included a 50cc class in the Ultra Lightweight event. The tiddler prize wen to Bruce Hain over Larry Simons, while John Bauskis took his CR93 Honda to the 125 victory over Tom Rae and Dodds. Pre-race favourite Len Atlee was a non starter after crashing in practice and injuring a shoulder.

Dodd’s first win for the day came in the six-lap Lightweight, when he led home the Yamahas of Doug Saillard and Terry Lauer. Few expected the rider from Fairfield to match Ron Toombs’ well-fettled 7R AJS, but that’s exactly what he did, leading home Toombs and Max Robinson to add the Junior to his tally. The main 12-lap Unlimited was a rematch, with Toombs again on his 350 and again trailing the flying Cotton home. Stan Bayliss’s Norton led home Brian Thomas on his G45 Matchless in the Junior Sidecar, but had to settle for third in the Unlimited behind the Vincents of Noel Manning and John Dunscombe.

Toombs takeover

It was September 1966 before the next motorcycle meeting at Katoomba. The Toombs stable had been boosted with Tony Henderson’s Matchless G50-engined Norton, and since Carruthers and Dodds had vacated the scene, the Sydney builder had become the man to beat wherever he appeared. As in 1965, Bauskis was the 125 winner, while Doug Saillard and Bob Pressley had a great dice in the 250 before Pressley got his Bultaco ahead to win by seven seconds. Having a form day, Pressley also headed B-Grade winner Terry Dennehy and Toombs for several laps in the Junior, with Ron gaining a narrow win over the howling Honda twin. Now aboard the Matchless, Toombs led all the way in the Unlimited, setting a new lap record of 65.8 seconds (117 km/h) to win from Garry Thomas on a Norton twin and Brian Coomber’s Triumph. Both Unlimited sidecar races went to Noel Manning, with Bob Levy spectacularly up-ending his outfit at Craven A Corner.

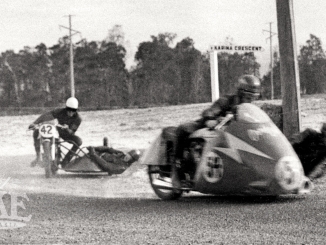

Despite the circuit’s unforgiving nature, the first two meetings had been fairly accident-free, with the fairly low average speed helping. In November 1967 the bikes were back again, and once again it was Toombs to the fore, arriving with a stable of four bikes. Len Atlee, on Clem Daniels’ CSD streeted the field in the 125cc event, setting a new lap record of 71.6 seconds in leading home Toombs on Jack Gates’ Bultaco. Now Cotton mounted, Atlee again made the pace in the 250cc event before Toombs, on Perc Howard’s new TD1-C Yamaha, swept past. Shadowed by dirt track star Ray Curtis on Norm Askew’s home brewed Suzuki twin, Toombs collected his first win of the day, slicing two seconds off Pressley’s lap record. The Junior was just like the good old days, with British singles taking all the places. Toombs’ 7R led home Elmer McCabe’s similar machine with Curtis on a Manx Norton in third. The Unlimited A Grade brought a strong field to the line, with Atlee’s 500 Norton holding sway until Jack Ahearn’s Dunstall Norton twin thundered past, followed by Bill Horsman and Toombs. Veteran Ahearn, who had 20 years racing behind him and still ten more ahead, held off Toombs to the flag, the latter demolishing his own outright record to 64.4 seconds. The race boded well for the 12-lap Feature A, but this time it was Dennehy’s 305 Honda that made the initial pace after Ahearn’s Dunstall expired on the dummy grid. The first three laps were breathtaking, with Toombs forcing his Matchless into the lead over a battling group of Atlee, Dennehy and Curtis, which came apart when Curtis crashed at the foot of the mountain. At the flag it was Toombs from Horsman and Queenslander John Warrian. Keeping the British-bike revival on track, James Marks won the Production Machine race on his Velocette Thruxton. The most spectacular incident of the day occurred in the 750 Sidecar event. Stan Bayliss was controlling the event when Alan Gittoes’ passenger fell out of the front of the chair exiting the Tunnel and was run over. The Norton pitched into the fence, tossing out the rider, and with the throttle jammed open, careered off down the straight at full bore before demolishing itself against the bank at the bottom of the hill. In the re-run Bayliss led home Barry Cowell, and made it a triple when he switched to his Vincent and defeated Manning in both Unlimited Sidecar events.

Loot for Lucas

The November date had become the traditional ‘season closer’ and for a change, the 1968 event was blessed with glorious sunshine, but in front of a paltry crowd. Geoff Lucas had made quite a name for himself on the fire-breathing Triumph special developed by Mark Walker, and on this occasion he did himself proud, twice defeating Toombs and lowering the outright lap record to 63.4 seconds. Yamaha-mounted, Toombs took his customary wins in the 250 and 350 races, while Len Atlee won the Ultra Lightweight on the CSD. Renewing their traditional rivalry, Noel Manning and Stan Bayliss fought out both sidecar events, with Manning top dog each time.

Catalina’s final fling as a motorcycle venue came at the Katoomba Grand Prix on December 7th, 1969. Since the Easter Bathurst meeting, when Toombs debuted the all-new TD2 and TR2 Yamahas, the old master had been virtually unbeatable. Now, several more examples of the new Yamahas had found their way into the hands of star riders including veteran Eric Hinton and young chargers like Laurie Turnbull. Bill Horsman was back with his quick 250 Bultaco, but despite the challengers, the day saw Toombs at his brilliant best, winning the 250cc, 350cc, Unlimited A Grade and Unlimited Feature events. In winning the Junior by a fraction of a section from Horsman with Turnbull third, Toombs established what would stand as the circuit’s all-time lap record – 62.15 seconds. In the 250, Tony Hatton, mounted on a heavily modified Yamaha DS6 with flat handlebars and no fairing, scorched off into the lead while both Toombs and Hinton made bad starts. It was only on the seventh of eight laps that Toombs nosed ahead to win. Against fairly thin opposition, Stan Bayliss won all three sidecar races. The last motorcycle race held on the circuit was the 12-lap Unlimited Grand Prix, and this time it was Turnbull who made the most of the push start. Toombs, on the Henderson Matchless, was soon onto his tail, but could not find a way through. Behind them, diminutive South Australian Ken Blake and Jack Ahearn, both on 650 Triumphs, battled with Len Atlee’s Norton and Sid Lawrence’s amazingly fast pushrod Velocette. Eventually and inevitably, Toombs wore down Turnbull, who held on for a brilliant second ahead of Blake.

And so the curtain fell on Catalina, at least as far as bikes were concerned. Sydney now had two operating road racing circuits in Oran Park and Amaroo Park, and no-one seemed too upset to see Catalina Park laid to rest. The ARDC had tired of loss-making meetings due to bad weather, and it seemed the public had also tired of making the long trek from Sydney when half the race-day could be spent waiting for the fog to lift. In Amaroo Park, the ARDC had a convenient and well-equipped base, and without them, the Blue Mountains Sporting Car Club had insufficient resources to carry on. The track languished for several years until it was partially revived for use during the short-lived made-for-television Rallycross craze – a combination of sealed and unsealed surfaces for modified saloon cars. The all-time lap record for cars is 53.6 seconds, an average of 139.6 km/h set by Leo Geoghegan in his Lotus 39 V8.

Despite the car driver fatalities and the dire predictions for motorcycle riders, there were no serious injuries during the five motorcycle meetings. Laurie Turnbull, one of the stars of the final meeting recalls that a fellow St George club member dropped his Aermacchi on the uphill run to Craven A. Unhurt, he clambered to his feet and in his haste to vacate the race track, jumped the inside fence and fell some considerable distance into the valley below, knocking himself about somewhat! Ironically, the motor sport career of former bike rider Len Deaton ended at Catalina when he crashed his new Brabham car and was badly hurt.

The bitumen roads that made up the circuit are still there, although no longer accessible by vehicle. Between races, the track used to officially become as scenic drive at a strict 60 km/h limit, but was closed after being regularly invaded by hooligans. It still makes an interesting walk, jog or cycle and in the clinical environment of today’s race tracks, is a chilling reminder of what used to be regarded as adequate circuit safety.

Story Jim Scaysbrook • Photographs: Dick Darby, Laurie Turnbull, Jim Scaysbrook