It was known as the Suicide Saucer, the Bowl of Death, or the Murder Drome, and for good reason. Many riders (including racing cyclists) lost their lives on the concrete banking before its demise, but the Melbourne Motordrome was a big attraction in a country struggling through tough times.

The engineers who designed the one-third-of-a-mile track estimated lap times might eventually reach 115 km/h, and specified the curvature of the banking to suit. Within two years of its opening, the lap record had soared to over 150 km/h. This forced riders to crank hard over on the sixty degree banking, searching for grip as they fought to hold their machines down to prevent them from sliding up above the broad red line that was painted halfway up the slope. Crossing the red line while cranked over was extremely hazardous – oil discharged from the total-loss lubrication systems made the paint as slippery as ice.

The Motordrome site was on the former Amateur Sports Ground – today the site of the Olympic Pool on the banks of the Yarra – which was directly serviced by the new Melbourne to Burwood electric trams running to the Melbourne Cricket Ground. It was first proposed as early as 1915, with ‘Motordrome Limited’ issuing a prospectus for 30,000 shares at 5 shillings (50 cents) each. In reality, the concept stumbled about for almost a decade before another group, headed by the ‘King of Sport’ John Wren, a boxing and turf promoter, gold mine owner, and political activist, who made his initial fortune with his own ‘tote’ based at Collingwood. As with just about everything associated with Wren, the Motordrome was surrounded in controversy from the start. Wren had already dabbled in motor sport, as far back as 1913, promoting “Rupert Jeffkins – the Speed King” (an Australian driver who had raced in USA), in exhibition races at Richmond Racecourse (which Wren owned).

Early rumbles

Since its inception in 1909, The Amateur Sports Ground had been poorly maintained by the various groups that used it, and in 1923, the Victorian lands Department controversially granted a Wren company, Melbourne Carnivals Pty Ltd, a five-year lease with a further five-year option, without the usual process of calling for tenders. Jacob ‘Jack’ Campbell, a manufacturer of bicycles from Prahan, was appointed as manager of the Motordrome. A major yike broke out between Melbourne City Council and the Lands Department over the lease of the ASG, and a further portion of Yarra Park which had been given over to Wren’s company for use as parking. The basis for the argument was that the public had not been consulted over the conversion of public land for commercial enterprise, but as usual, Wren had his way.

Plans for the Motordrome were drawn up by Jack Prince, an Englishman who had spent much of his life in the USA racing bicycles. Before 1910, Prince began to design and build ‘Motordromes’ inside fairgrounds, and soon had a string of tracks in America. However an appalling toll of death and injury, not just to competitors but to spectators, led to a major backlash at local government level, and most of the US ‘bowls’ were gone by the time the First World war ended. In Melbourne, Wren re-started construction of his Motordrome, which had been halted by the war and a shortage of building materials., with Prince as the principal engineer. Wren’s company claimed the total cost of construction was a staggering £40,000 ($80,000) by the time the track opened for business.

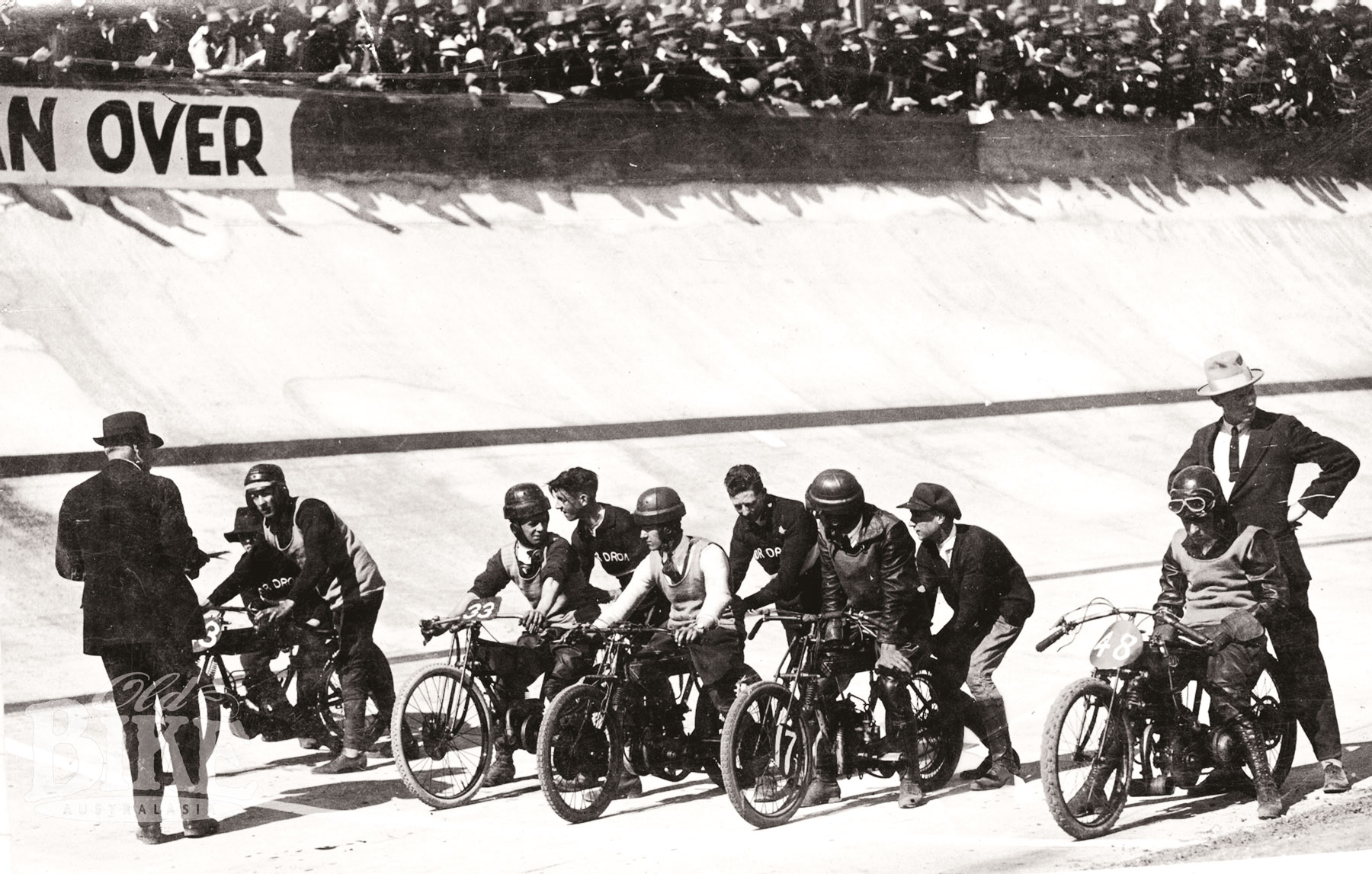

Vast amounts of concrete went into forming the bowl, which rose from grass level at 48 degrees to the Red Line, then steepened to a black line, one metre from the top. The last section was vertical, with an overhanging lip protruding 30 cm, officially known as the Safety Rim. This was Prince’s solution to prevent vehicles from launching themselves into the crowd, but it was only partially successful. The rules stated that solo motorcycles were not allowed to ride above the red line, except to overtake. A sidecar outfit could race anywhere below the black line.

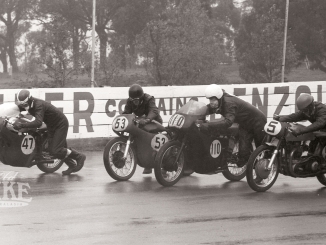

The projected opening date came and went on at least three occasions, but finally the gates opened on Saturday, November 29, 1924. As the track lighting installation had fallen behind the contract date, the first two meetings were held in daylight. This was very fortunate for us, otherwise we would not have the remarkable action photograph reproduced on these pages, as synchronised flash had yet to be invented. For that opening meeting, the promoters imported four top American board track stars with their specialised racing machines. They were Paul Anderson (8-valve Indian), Johnny Seymour (Indian), Ralph Hepburn (Harley), and Jim Davis (Harley). Much to the consternation of the local riders, the Americans insisted all competing machines should have their brakes disconnected. The locals protested but the steward, Fred Yott, upheld the Americans’ request.

On the day, the Harleys of Hepburn and Davis failed to arrive, and both rode locally-supplied RA Douglas twins. In the final of the Solo Scratch Race, Seymour and Hepburn were declared to have dead-heated (although most thought Seymour had won, the bookies were happy), and the crowd went home satisfied. Seymour badly broke a leg at a later meeting, while the local star, Charlie Disney, who had shown himself well capable of taking on the imports, had a leg amputated after a grass track accident in February, 1925.

Around 15,000 had packed into the continuous open grandstand around the top of the bowl, and although it was expressly forbidden, many hung over the top of the lip for the ultimate view. This was not the only rule broken, and the riders themselves were the worst offenders. Sensing they could get away with anything, the Red Line soon became a farce. Riding the Red Line gave no thrills either to competitors or to the public and taking advantage of the alibi of attempting to pass, riders shot above the Red Line until riding the Black Line (or riding The Lip) was the only way to win. This involved hurtling around the saucer on 50cm of perpendicular, oil-soaked concrete, directly below the overhang. In doing so, rider and machine were actually horizontal, held up by centrifugal force.

Action aplenty

The big vee-twins proved a real handful on the tight track, and from the second meeting, solos were restricted to 500cc. By the time of the third meeting the track lighting was operational and from then on it was ‘Saturday night at the Drome’. The new sport soon gripped the imagination of the public; the thrill of close-quarter, high-speed racing under lights, the noise, the smell, the glamour and the excitement far outstripped any other entertainment and attendance figures regularly soared past 20,000. To keep the crowds coming, the promoters organised a variety of attractions, including motor-paced pushbike racing. Each team consisted of a pacer on a large-capacity machine, usually a four-cylinder Henderson or a big twin Super-X. The seat was directly over the rear wheel spindle, as close as possible to the following rider. Handlebars were extended about one metre to the rear, and a free-running roller was fitted at axle height immediately behind the rear wheel. The pushbike itself was specially constructed to get the rider as far forward as possible, the front forks usually being reversed to quicken up the steering. A huge chainwheel was fitted to achieve the necessary high gearing, as motor pacing more than doubled the speed capabilities of the humble bicycle.

The art of the exercise was in the joint skills and co-ordination between the rider and the pacer – the rider needing speed and stamina, and the pacer needing almost psychic powers to judge how fast he could go and still keep the rider in tow, with his front wheel just nudging the roller. A fraction too much throttle and the rider would lose the slipstream and slow dramatically as he ran into turbulence. The chief exponents of this art were Bob Finlay (who’s brother Bert was a leading BSA agent with his sons Alec and Bert Junior), pacing Hubert Opperman. Cars also ran at the ‘Drome, but they never achieved the popularity of the bikes. This was partly because the track was too narrow for overtaking, so the car races were run on the pursuit system, two cars only, starting half a lap apart.

The first full season was drawing to a close without any serious accidents, despite the many infringements of the rules, when on March 30, 1925, a massive crash left three riders, Alec Staig, Allan Bunning and Hodge, dead and forced the track to shut two weeks early due to the uproar. To counter the periodic opposition to motor sport, the Motordrome staged all sorts of alternative attractions. According to Wren’s biographer, James Griffin**, “the search for novelty reached farcical lengths, with children driving two-wheeled carts pulled by billy-goats. Ostriches imported from South Africa were set up with cardboard cut-outs of jockeys and names of well-known horses to race around the track. The ostriches, however, refused to perform past their bedtime. Money had to be refunded.”

The Drome was so small that only four solos were permitted in any race. Most races were over three laps, or one mile, so it was all over in less than a minute. This allowed motors to be run in an extremely high state of tune, with drastic lightening of both engine and cycle parts. It was common practice to drill out the centre of the con-rod for lightness, and extremely high compression ratios were employed with exotic fuels. Performance increased to such an extent that the capacity limit for solos was dropped to 350cc, making the popular marques Douglas, Indian, Harley, Chater Lea, Rudge, Triumph and New Imperial, as well as the Big Port AJS. Hepburn was so impressed with the AJS that he bought his own B4 model, applying some of his tuning wizardry and thrashing the official AJS team, headed by Charlie Griggs. Griggs himself became a statistic in 1926 when he crashed at the top of the banking, grinding himself to a pulp on the jagged concrete lip; his machine flying over the top and seriously injuring a young girl.

Jumping Jack

One of the most remarkable riding and tuning feats was that of a dapper, flamboyant Englishman with the unlikely name of Jack Sidebottom – a sales rep for the Sydney AJS agents P&R Williams. On a sales promotion tour riding a G6 AJS, Jack turned up at the empty Motordrome one weekday and began reeling off a few unofficial laps. A caretaker yelled at him to stop, and when he refused, threw a plank of wood onto the track, which Jack struck at high speed, severely bending the AJS. Jack hung around Melbourne until the bike was repaired and the fuss over his absence from his workplace in Sydney had died down, then rode back to Sydney to fetch the well worn racing GR7 AJS on which he had achieved success at the concrete Maroubra Speedway. Aboard this dilapidated heap, the fearless Sidebottom became a real force at the Drome, and was credited with the outright all-time solo lap record of 93.75 mph. Following Sidebottom’s success, the Indian agents, Rhodes Motors, fitted a GR7 cylinder head to a single cam Indian Prince and achieved considerable success with it in the hands of Bill Chitts and Isle of Man team rider Spencer Stratton.

The promoters were always dreaming up new ways of keeping the excitement at fever pitch, such as putting on “World Championships”. The winner of more than one such title was another AJS rider, Hughie McKay, while others to achieve fame on the marque included Jimmy Stewart, Arthur Simcock, Percy Day and Clarrie Clarrigg. Similar confusion surrounded the lap records. One journal of the day credits the sidecar lap record to Con McCrae, father of Bathurst legend Sandy McCrae, at 90 mph on a Brough Superior. Another claims the ultimate three-wheel mark went to Sid Gower on an Indian Special, a 1200cc side-valve “Altoona” Indian fitted with OHV four-valve heads.

To capitalise on the craze for dirt-track ‘Speedway’ racing, which had originated in Newcastle and quickly spread around the country, a tiny dirt oval was constructed on the infield of the ‘bowl’ and ran its opening meeting in October 1928.

On February 9, 1929, the Motordrome hit the headlines again when Nat Brown lost control of his machine after blowing a tyre, which jettisoned the rider and careered up the banking to where two 16-year old spectators, George Goldsmith and William Bell, were hanging over the lip, enthralled by the action. Bell was decapitated and Goldsmith died soon after being admitted to hospital. The track was closed for the rest of the season but again reopened for the 1929/30 summer season, where novice rider Reg Maloney became the next victim. The track reverted to pushbikes only, but within a year the motorcycles crept back, with star names like Jimmy Wassall and Jim Pringle, both now established road racers, as the main attractions. On January 2, 1932, Wassall was making his usual charge through from the back mark when two other riders, Syd Bryant and Danny Maughan, crashed in front of him. With nowhere to go, Wassall ploughed into the wreckage and slammed headfirst into the dreaded lip, fracturing his skull and passing away the next day. Three weeks later Bill Wood was killed in a similar fashion. The promoters, already under fire from riders who claimed they had not been paid, announced there would be no more solo racing, but a sidecars-only program failed to lure the spectators. Sid Gower topped the billing at the final meeting, reportedly setting the all-time Sidecar lap record.

As the end of the second five-year period of Wren’s lease loomed, it became obvious that an extension would not be granted without vigorous opposition. The new Minister for Lands, Mr Dunstan, made it clear that he was not in favour of renewing the lease, but in any case, Wren’s interests had shifted to ownership of horse racing courses not only in Victoria, but New South Wales, Queensland, and Western Australia. For a while he proposed that Melbourne Football Club play their home matches at the Motordrome, but nothing came of it.

On April 8, 1933, a group of veteran riders held an unofficial meeting on the Motordrome. It was a solemn occasion – a salute to the men who had given their lives inside the confines of the concrete cauldron. Two days later, heavy charges of dynamite blasted the Motordrome out of existence. The Olympic Park dirt track speedway was later constructed on the same site, but it never achieved the fame and fortune of the Motordrome and closed shortly after the Second World War.

**John Wren. A life reconsidered. (Scribe)

Story by Paul Reed and Jim Scaysbrook • Archival material from Brian Greenfield