From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 27 – first published in 2011.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Michael Andrews, Don Cox, Jack Ahearn archives, Phil Purdue, Jim Scaysbrook

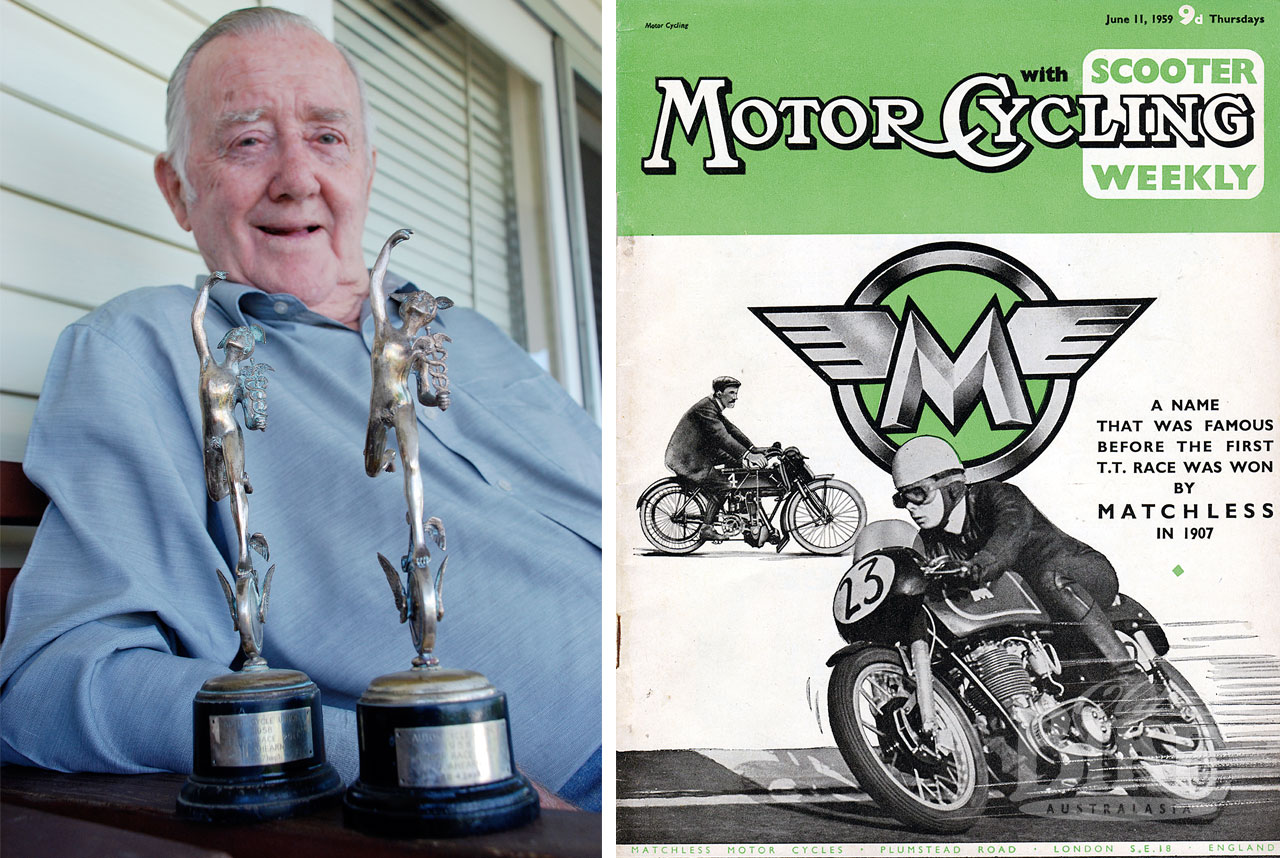

Big brother to the 350 cc AJS 7R, the Matchless G50 came into being in 1958, and Aussie Jack Ahearn was the first man to race the prototype.

The venue was the 1958 Isle of Man TT, and Jack has mixed emotions of that historic week. “It wasn’t my favourite motorbike,” Jack says with some conviction. “I think they (AMC) wanted people to know they were going to start making a 500, so it had a big red tank with Matchless on it, but it really was just a 7R bored out with a big heavy piston. With the really tall gearing for the TT it only fired about every second lamppost, and that was no good for the gearbox so that gave up. But later on, the G50 became pretty good, maybe even better than the 500 Manx.”

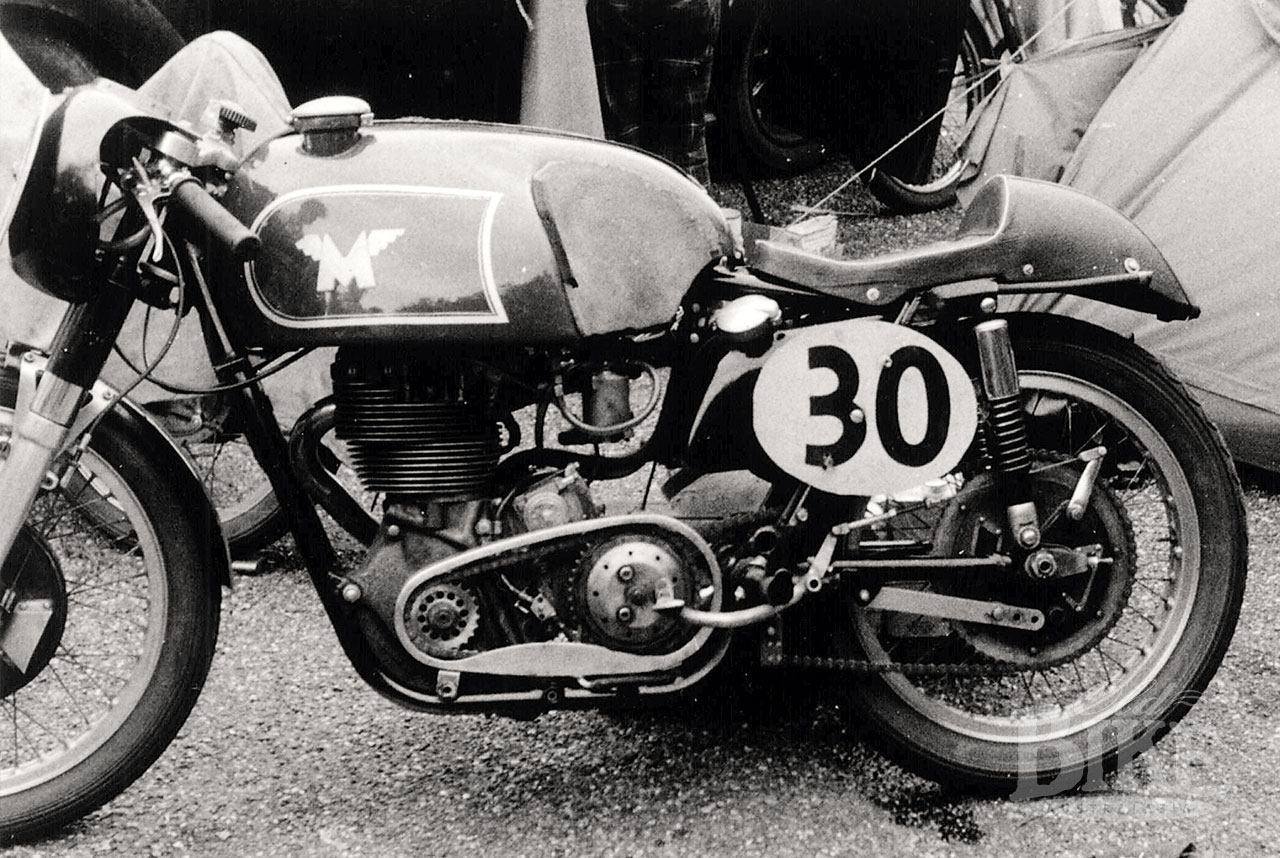

Perennial privateer Jack, always a Norton man, had a change of direction for the 1958 European season. “After winning Bathurst at Easter I thought that might be good enough to get a works ride, so I wrote to Jock West at AJS and he said ‘Yes, come over, we’ll give you something’. When I got there (to the AMC factory in London), he presented me with a 7R – last year’s experimental model that had been left lying around in the factory. I had to buy a fairing and do a lot of work on it, but it was hopeless, I could have run faster. I was about to give it up but they said ‘you can ride our new G50 at the TT along with the 7R’. I had ordered a new 500 Norton so I sold that to a New Zealander and waited at the TT for this new G50. Then, at the beginning of practice week, AMC’s head designer Jack Williams arrived with a machine with a red petrol tank emblazoned with the flying M of Matchless.” It was listed as a Matchless 496 cc and sported a big capacity fuel tank from the G45, but painted red instead of the usual black and silver. The engine of Jack’s G50 was some way from what appeared later in the year as the production G50, and was limited to 7,000 rpm.

Just what was inside that engine, or its exact capacity, is still unknown, but it used 7R valves and most likely had a capacity of around 400 cc. “It was slower than the 7R”, says Jack with perhaps a touch of exaggeration. “In the race it gradually lost the gears until there was only top gear left on the last lap. I just dragged it around and finished about last.” Not quite. Stuck in top gear or not, Jack must have been going quicker than he remembers, because he came home in 29th place at an average of 88.71 mph – good enough for a Silver Replica. His last (seventh) lap at 27 minutes 43.6 was more than two minutes slower than the previous six, dropping him out of the top 20. In fact, the gearbox problem had been most likely caused by the primary chain oiler packing up – the chain was bone dry and breaking up, and Jack coasted over the line with a silent engine. Nevertheless, the saga of the Matchless G50 had been born.

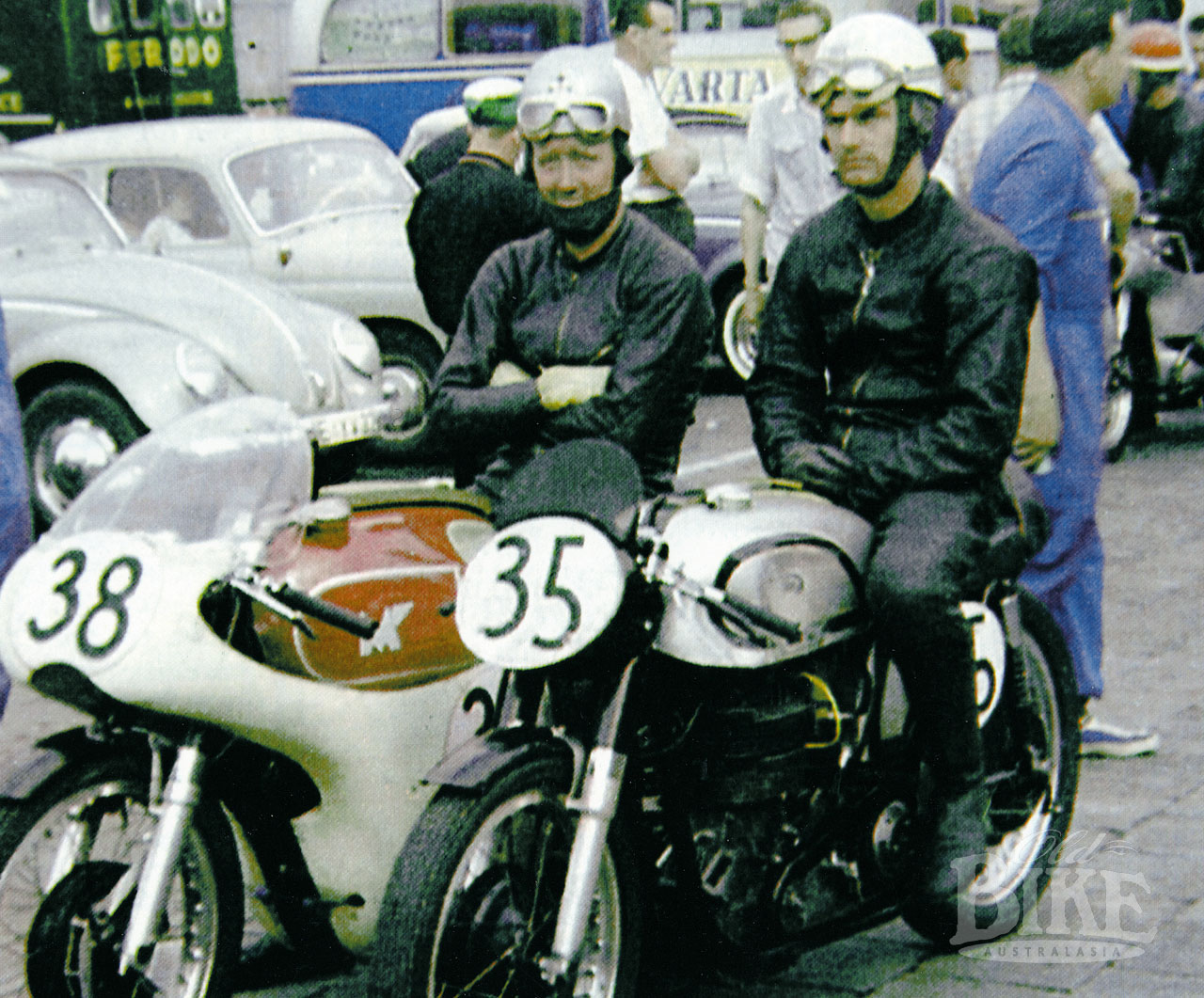

After the TT, the AMC mechanics rebuilt the gearbox and Jack took the G50 to Europe for the Dutch TT (11th), a non-finish at the German GP, 13th in Sweden and 12th in the Ulster GP – not the kind of results he had been hoping for. Somewhat downcast after his poor season, Jack abandoned his last scheduled appearance on the G50, at the Scarborough ‘International’ meeting in September 1958, and the ride was taken over by compatriot Harry Hinton Junior. And he made the most of it, besting Bob McIntyre in a thrilling duel for third place in the 500 cc Final won by George Catlin from Bob Anderson. The following week at the season-ending Mallory Park meeting, Hinton crashed his 7R in practice and broke a collarbone and the G50 ride was taken over by John Holder, who finished sixth in the main 500 cc Challenge Trophy.

“Just a bored out 7R” it may have been, but the promise was clearly there. In fact, it was not uncommon for 7Rs to be enlarged by private owners, particularly after the bore and stroke was revised in 1956. Originally, the engine’s dimensions were 74 x 81 mm – identical to a Mk 8 KTT Velocette, but this was changed in 1956 to 75.5 x 78 mm. The simple expedient of fitting the larger bore top end to the longer stroke bottom end produced 362 cc, giving the owner a Senior class mount, which, on occasion, just happened to find its way onto the grid for the 350 race as well!

The greatest drawback in obtaining a full 500 cc capacity was the limit of the bore size available using the standard 7R crankcases. The positioning of the through-bolts joining the cylinder head and barrel to the cases limited the maximum bore to around 86 mm, but by slightly repositioning the hole centres, a larger sleeve with a 90 mm bore was possible. Just why this should have taken so long is systematic of the torpor afflicting the entire British motorcycle industry and the tight-fisted AMC board in particular.

But eventually it did happen. At the Earls Court Show in November 1958, perched high on the Matchless stand was the new production Matchless G50, priced at £430/7/9 (£12 dearer than the 7R) with orders taken for the 1959 season. A couple of months prior to this, world champion John Surtees and journalist Bruce Main-Smith had tested the prototype G50 and a second version at Brands Hatch, accompanied by Jack Williams and works mechanics. The G50 ridden by Jack Ahearn in the TT still had the earlier frame, with a wider engine cradle that had shown a tendency to scrape the bottom frame rails under hard cornering, while on the second, newer machine, the frame cradle had been narrowed, the engine repositioned slightly higher in the frame, and the exhaust pipe tucked in closer. Two weeks later, Scot Bob McIntyre had a run at Silverstone, testing new Avon tyres with a view to racing a G50 in 1959.

The 1959 TT included two new events, dubbed Formula One, in both Junior and Senior categories, which excluded works bikes and should have been custom made for the G50. But the leading men stuck with their Nortons, and only one Matchless made it home in the top 15 in the Senior, that of Derek Powell in 7th place. It was a happier story in the Junior Formula One with Scot Alistair king winning on a 7R. In the wet Senior TT, Powell improved to 4th place on his G50, behind the Works MV Agusta of John Surtees and the Nortons of Alistair King and Bob Brown. Also riding G50s, Alan Shepherd and George Catlin finished 7th and 8th respectively.

Gradually the G50 found favour amongst the privateers, the ease of maintenance, oil tight motor and lower running costs compared to a Manx appealing to many, even if the Matchless was still a couple of horsepower shy of the Norton. On some of the tighter English tracks the G50 was reckoned to be a better tool than the Manx, due to the flexibility of the engine. Production for 1960, 1961 and 1962 was around 40 complete units per year, and for the 1962 production year, the G50 had received a small makeover, with the inlet valve increased in size by 1/8 inch to 2 inches, and the outer timing chest modified to allow the exhaust pipe to be tucked in closer. But in early 1963 came the bombshell from AMC that there would be no more racers; an announcement that sounded the death knell for the 7R and Manx Norton as well. At the close of play, only 180 complete G50s had been produced. It was a bitter blow for road racing the world over, which was already deeply affected by the downturn in motorcycle sales that was to continue for several more years. There were in fact, G50s of a sort made in 1963 – 25 machines called Matchless CSR (or Golden Eagle in the USA) produced for the US market with G50 engines in the road-going CSR chassis to comply with AMA requirements whereby racing machinery had to be based on street bikes.

The demise of the British production racers had the effect of giving birth to a cottage industry to keep existing machines running. In the case of the G50 and 7R, salvation came in the form of sidecar racer Colin Seeley, who had campaigned a G50-engine outfit with considerable success. After making lightweight frames to take G50 and 7R engines for a couple of years, Seeley took the plunge in 1966 and bought out the remains of the AMC Racing Department, along with the tooling and manufacturing rights for the engines and spares. The move prolonged the life of the venerable singles for several years (and gave birth to the G50-engined Seeley Condor road bike), but for the purists, and the record, the last real G50 had unceremoniously gone out the doors of the AMC factory in Plumstead Road, Woolwich, in the early weeks of 1963.

A G50 resurrection

The advent of Historic Racing in the mid 1970s meant a new lease of life for the old British bangers – bikes that had been consigned to the shed since being chased off the tracks by the new wave of Japanese two strokes. Some of the original riders were still around to give their old steeds a few airings too, but the rigours of competition soon began to show the natural atrophy that seems to occur with racing iron. For the G50, the original magnesium crankcases have a definite shelf life before becoming brittle and cracking, and aluminium replacements are not exactly thick on the ground. Certain components – conrods from Carillo, pistons from Mahle, valves sourced from other makes and so on – meant that the original engines could continue to run, if not race hard.

By the mid-1980s, Historic racing was booming and an industry had sprung up to supply parts, and eventually complete Manx Nortons and Matchless G50s. In the case of the latter, cylinder heads made by Mick Rutter in the UK were the first major component manufactured, but soon complete engines were available from several sources, including Germany. Noted collector George Beale began offering complete bikes, in original specification as well as a special lightweight version designed for the International Historic Racing Organisation, which these days runs major historic events at traditional road circuits like Chimay and Mettet in Belgium and Schleiz in Germany. If you have a well-fettled G50, there’s no shortage of events in Europe.

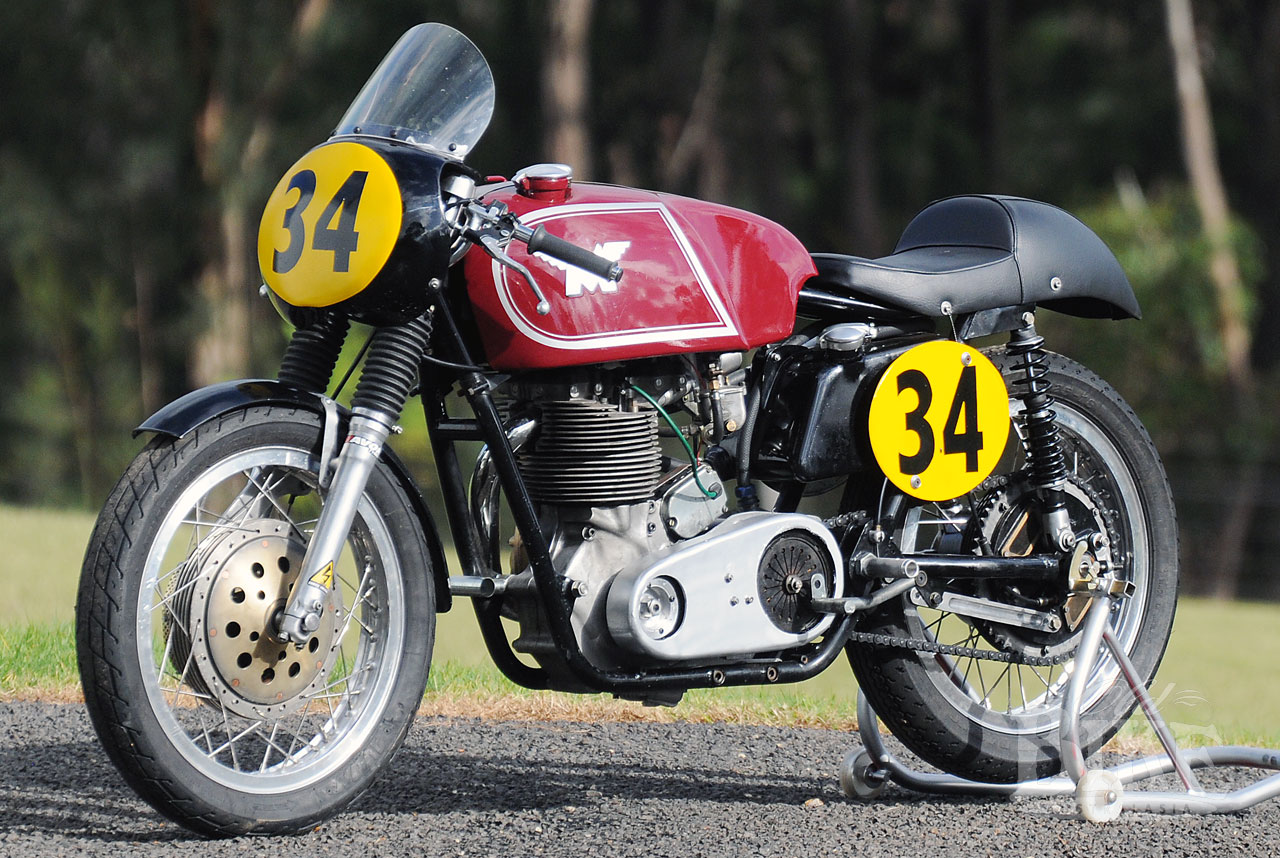

In 2010, I decied to build a replica G50, using the best parts I could find. This began with a new engine from Mick Taberer in England. Mick’s engines, while remaining faithful to the original concept, have subtle and worthwhile internal mods. The bottom end incorporates what probably should have been done in the first place. Instead of pressed-up crankshaft halves, each flywheel and its shaft is a one-piece forging in EN36, ground and hardened. The drive side main bearing is needle roller with an external seal, with a ball and roller bearing on the timing side. A forged Omega piston sits atop the forged conrod.

The next temptation presented itself during the 2010 Classic Festival at Pukekohe when I was discussing my new ‘project’ with Peter Lodge, the Auckland engineer and builder of the astoundingly-rapid pushrod ES2-based Nortons. Peter had an idea to build a G50 and had got as far as constructing a jig and making a complete frame, but as he had abandoned the idea, the frame was now surplus to requirements. Peter had not gone as far as making the swinging arm, but had it all drawn up and with a factory full of the latest CNC machinery, the various lugs and fittings were produced. The G50 swinging arm uses tapered tubing, and in the interests of originality, so did Peter, turning the tapered tube from solid before bending it into shape. The rear hub came from Molnar Precision Engineering in England, along with the fork yokes, seat and ancillary fittings. Also from England came a brand new 1 1/2” Amal GP carburettor, supplied by Burlen Fuel Systems.

A genuine petrol tank was sourced from the estate of the late Allen Burt, but the oil tank needed to be made, and who better to do so than master tin-basher Steve Roberts from Wanganui, NZ, the man who built the superb monocoque Suzuki TT F1 races campaigned in Europe by Dave Hiscock. Ross Graham found he had a set of original G50 Girling rear shock absorbers in his workshop, so these were fitted in the interests of originality.

A gearbox was no problem, since Bruce Verdon builds complete AMC racing boxes at his TT Industries base in Nelson, NZ. These are available in 4,5 or 6 speed, with either magnesium or aluminium casings. I chose a 5-speeder in aluminium, along with one of Bruce’s toothed-belt primary drive. Basically this just left the front end, which was put together by Martyn Adams at Birdwood Motorcycle Engineering in South Australia, using AMC/Matchless sliders with Spanish Betor tubes and internal damping mechanism. An Italian Oldani 230 mm magnesium twin leading shoe front brake came from Motocicli Veloci in Italy. The fibreglass nose cone was one of the last jobs produced by Brian Crane before Homebush Fibreglass closed its doors after 40-odd years and countless Norton fairings, and into this went a replica Manx/7R conical tacho built by Dennis Quinlan.

The man who put all this together was Peter Campbell, in Goulburn. Peter made the engine plates, footrests, rear brake pedal, gear lever, float bowl mount, rear axle, front brake stay and various other fittings. Rod Tingate, another master craftsman from Melbourne, made the clip-on handlebars. The aim was to make the Australian Historic Racing Championships at Phillip Island in September 2010. And we made it, just. The G50’s third run came at the Easter 2011 Broadford Bike Bonanza. With four other bikes to ride I was more than happy to hand the G50 over to 4-times World Champion Hugh Anderson, who galloped it at a fair lick and looked just like he did nearly 30 years ago when he raced his own G50 in the early IHRO events in Europe.

Subsequently, a set of Ceriani replica 35mm forks were fitted, along with a Fontana doubled-sided TLS front brake. And that’s the specification the G50 was in when it was sold to Melburnian Bob Rosenthal in 2014. Bob raced it for the next seven years, until a nasty crash at Sydney Motor Sport Park (on another G50) convinced him it was time to hang up his helmet for good. The G50 is now for sale – a ready made ticket to any aspiring Period 3 500cc Classic racer.

For sale: Matchless G50 replica 1962

Engine has done 165km since rebuild and bike has covered 4562km since I bought it. Full documentation available along with my running log book and workshop manual. Spares include original fuel tank, spare new fairing, new Krober tacho.

Contact Bob Rosenthal – Mobile +61 409 262 727 or by email: rosentbob@gmail.com