From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 67 – first published in 2017.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: Mat Clancy and FoTTofinders.

In that hot bed era of motorcycle development – the ‘thirties – the twin parameters of performance, namely power and handling, came under equal and increasing scrutiny. In the case of the latter, there was plenty of scope for innovation, given that the standard designs had changed little in several decades.

The girder front fork, in its various permutations, was still the accepted standard, and had thus far resisted innovations such as leading link, and even, back in the days of the Ner-a-Car, hub-centre steering. The coming thing was the fully telescopic fork, popularised by several manufacturers, notably BMW, and copied by many, including Norton.

But ‘teles’ came with numerous built-in restrictions and shortcomings. For a start, the thin diameter front tubes were subject to stresses of all the wrong kinds, particularly under braking, when the weight transfer placed major strain on the sliding surfaces and their ability to continue to slide happily. However by the early ‘eighties, the move was afoot to supplant the thinking that ‘teles’ were the only solution. In the racing world, the French Elf, with its radical front end, showed that it was quite competitive in the hands of British star Ron Haslam, while Bimota pressed their own radical creation, the Tesi into production, replete with its own spin on the hub-steer front end and an astronomical price tag to suit. None of these efforts, although commendable, really made inroads into the world of volume production, but meanwhile, in Germany and Japan, other concepts were being studied closely.

BMW had never been shy in coming forward with unique thinking. After all, they had produced the first hydraulically-damped telescopic fork in 1935, and had stuck with the Earles-design of swinging arm front suspension, aka leading links) for decades. In 1981, BMW adopted the Nicol Link system, developed by Brit Hugh Nicol, which was marked as the Telelever – the idea being to isolate steering from suspension, which is what had been the aim all along. It also isolated braking from suspension, thereby eliminating one of the main drawbacks of the telescopic system. The system also allowed the steering geometry to remain constant, reduced the tendency for the front end to dive under braking, and because the front wheel was no longer heading back towards the engine whenever the forks were compressed, designers were free (or freer) to experiment with weight distribution and the placement of the mass of the engine.

Interestingly, at about the same time as BMW was embracing the British Nicol concept, Yamaha was similarly engrossed in studying a system developed by an American company called RADD – Rationally Advanced Design and Development, under the engineer James Parker. In 1987, Parker modified a Yamaha FZ750 to create what he called the MC2, which incorporated his design of front end using a car-type upright to hold the front wheel and brake calipers, pivoting by means of upper and lower suspension arms, or pull-rods. It was actually the steering process, rather than the suspension side, that had puzzled engineers for ages, and Parker’s solution was via what he termed a ‘steering shaft’ – in effect a telescopic unit itself – which incorporated special bearings to allow the shaft to move with the suspension. Parker had studied the Elf bikes, and particularly why they had not achieved the success he felt was deserved. He felt the problem was ‘bump steer’, whereby during the suspension’s travel, changes in the angles of the linkages produce unwanted input to the front wheel, and hence, the steering. Parker’s “steering shaft”, which he patented at considerable expense, was the solution. The original Honda 600-engined development machine demonstrated Parker’s ideas, but failed to convince Honda to take up the scheme. Next stop was Yamaha, who showed a little more interest, and the prototype was test ridden at Willow Springs Raceway in Southern California by no less a figure than Wayne Rainey, who gave it the thumbs up. This was enough to swing Yamaha to support Parker’s project, providing an FZ750 as well as the input of their California design studio GKDI, which produced the bodywork for what became the MC2. Late in 1987, that machine appeared at the Milan Show, and a little further down the track, Yamaha entered into an agreement with Parker to access his patents for the production of an all-new sports touring machine, based around the successful FZR1000 power plant.

This was to evolve into the GTS1000, but along the way, the svelte MC2 concept added considerable bulk, and although Parker went to Japan several times to view the progress, he was not permitted to have any engineering input. He said later that he only ever saw the bike fully clothed in its extensive bodywork, and only had the opportunity to measure the front end after the GTS1000 had reached the production stage. At that point, he realised that his design had been compromised and that the upper arm of the front suspension was too short, meaning that rake and trail increased with steering angle, producing heavy steering at slow speeds.

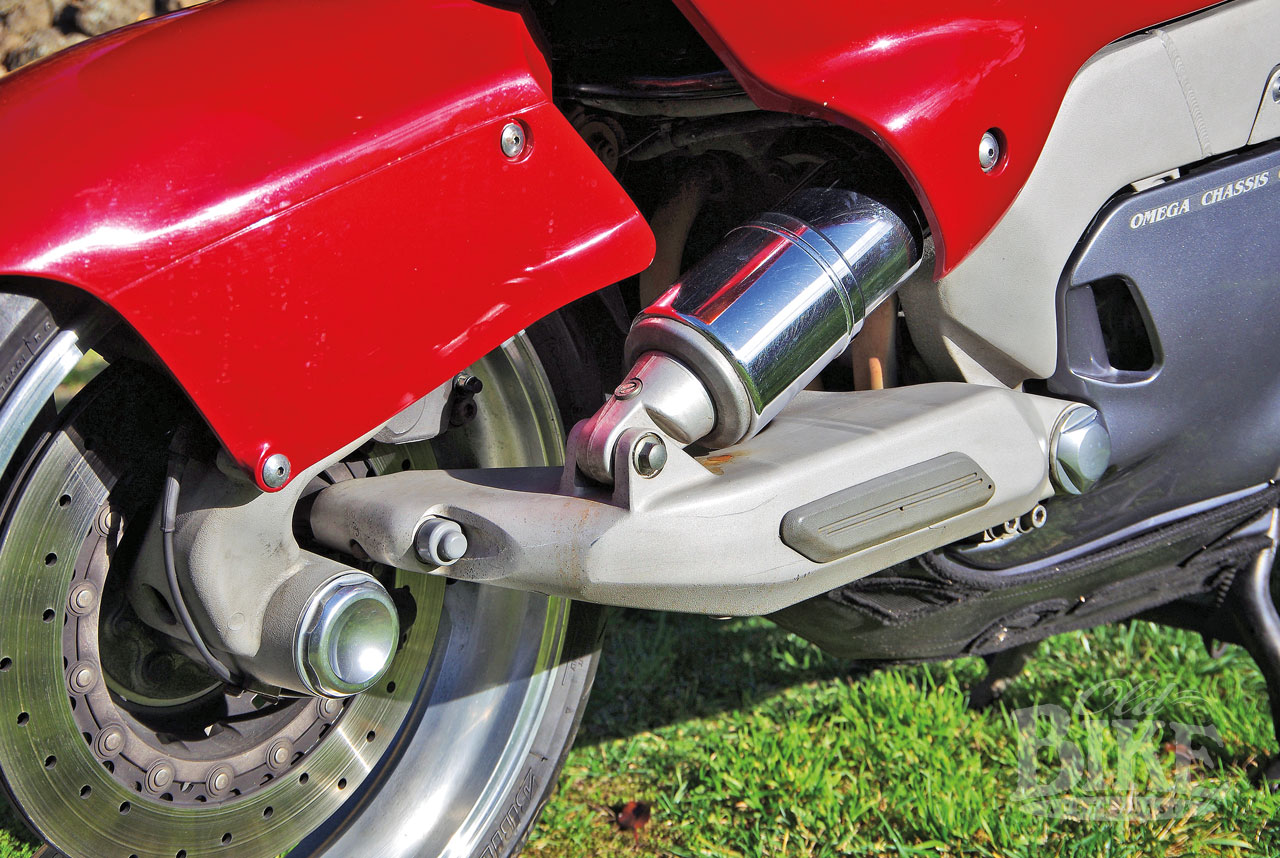

The GTS1000 duly appeared, slightly flawed front end and all, while Parker moved on, producing a new Suzuki GSX-powered model which further refined his theories. By 1993, the GTS1000 was on sale, but at $21,500 plus on-road-costs in New South wales, it was a luxury unit indeed. The GTS was marketed as incorporating the Yamaha Omega Chassis Concept – Omega chosen because the frame as such resembled the Greek letter (insert symbol). Because the loads generated from the front suspension were now transferred (via the swinging arm) back to the front of the chassis rather than up to the steering head as on a telescopic-fork bike, the frame could be totally redesigned. That frame consisted of horseshoe-shaped cast aluminium sections welded together, plus bolted up lower sections which were removable to allow the engine unit to be dropped out. Suspension at both ends was by swinging arm – the rear mounted in the conventional way through the main frame behind the gearbox and the front, single sided arm pivoting from the forward casting below the line of the crankshaft. To permit the required steering lock, the front swinging arm was curved, with a rather massive single shock absorber running from the arm back to the frame near the cylinder head.

So that’s the suspension side. As previously noted, the steering was a completely separate exercise. From the upright holding the front wheel on the left side, a steering arm with ball-joints at each end connected to a junction box, from which the telescopic arm (the ‘steering shaft’ from Parker’s original design) ran to the steering head, which was controlled, as normal, by handlebars connected to a stem. The huge 330mm front brake sported an opposed six-piston caliper, with Yamaha’s ABS, which itself had been developed on the FJ1200.

But while the radical front end was the visual signature of the GTS, it was by no means the only innovative feature of this quite daring motorcycle. Although the engine was derived from the five-valves-per-cylinder FZR1000, it was detuned (and limited to 100 horsepower worldwide) with lower compression and milder cam timing, with Yamaha’s own Electronic Fuel Injection. This used sensors for throttle position, air density, engine revolutions, coolant temperature and the oxygen content in the exhaust system, with continuous adjustment to maintain optimum mixture and fuel economy. Inside the exhaust system lurked a three-way catalytic converter, which was claimed to reduce harmful exhaust emissions by 60 percent.

In terms of fit-out, the GTS was fairly plush, with an electronic fuel gauge, clock, anti-theft ignition, a choice of two screens and a generous pillion seat. Genuine luggage was also available – at a price. One styling feature that received a less than enthusiastic reception was the fuel tank, or rather, what looked like the fuel tank. With the engine block and head cantered forward by almost 45 degrees, the fuel injection system intakes sat vertically, capped by a voluminous airbox. This relegated the fuel tank itself to a space above the gearbox, with a plastic shroud encasing the whole lot.

A short life

For a motorcycle which must have absorbed a considerable budget to develop, the GTS1000 enjoyed a very brief existence; on sale for just two years in North America, although it remained available in other markets a bit longer. The reasons for this are many and varied, but one is that Yamaha tried to market the machine as both a sports bike and a tourer. The riding position, with the rider’s weight forward, was a bit too sporty for long distance touring, but the engine, detuned from the FZR’s angry 130 hp to 100, ran out of breath well below the 10,500 red line. The milder spec was also intended to boost low and mid-range grunt, but needed around 6,000 on the clock before it really got moving. There was also criticism of the front brake, with claims that the ABS was over-sensitive, and that at low speeds the bike felt heavy and unresponsive. And then there was the price. Any or all of these factors may have been responsible for sluggish sales in the target market of USA – less than 30 units were sold in Australia – but buyer reluctance has always been influenced by fashion, and convincing riders that the long-loved telescopic front fork was dead was never achieved in the case of the GTS1000. In the eyes of Joe Public, the GTS was unusual looking, had none of the exotic design flair that graced the other quirky front end model, the Bimota Tesi, and was expensive (although at US $12,999 was less than one third of the Bimota’s price ticket in America). It was also prodigiously thirsty, British testers complaining of a fuel range of just 120 miles and consumption of around 33 mpg.

Today, the GTS1000 is a rare bird, but it always was. Spares are not exactly plentiful, but there is an Owners Club with nearly 400 members who assist with locating parts, and rightly regard the model as a cult classic.

Our thanks to Jeff McDonell for the opportunity to photograph his GTS1000. Melbourne-based Jeff bought his GTS1000 from a collector in Queensland, and says he was attracted to the model by the uniqueness of the front end. “I like bikes that are a bit different, plus the specification was very good, with EFI, ABS, a catalytic converter, alloy frame, all pretty swish for the day. The front brake is very good and it sits in the centre of the hub and is supposed to resist twisting. I have done a couple of long rides but I can’t really say I feel a lot of difference (with the front end) to conventional bikes. It is a heavy bike, but once you’re under way you don’t notice the weight.”

An unlikely TT star

As a Yamaha dealer, as well as a talented road racer, Steve Linsdell was always keen to promote the company’s product. Steve’s business, Flitwick Motorcycles, in Bedfordshire, UK, had entered Yamahas at the Isle of Man TT for several years and by 1993 he was an accomplished TT rider, as well as on other road circuits like the North West 200. In 1993 his sponsor, Steve Bond, entered him on a YZF750, but Linsdell said it wobbled so badly on the TT course that he decided to create a special bike on which to tackle the 1994 Formula 1 TT. Because the TT rules stipulated a maximum of 750cc, he slotted the YZF750 engine into the GTS1000 chassis, and despite the package being rather heavy, he finished an excellent 8th place, recording 167 mph (269 km/h) through the speed trap. A year’s development, which included fitting a slightly narrower front swinging arm and a lighter front wheel produced 6th place in the 1995 F1 TT, with a fastest lap of 117 mph (188.4 km/h). Not bad for a lightly tweaked touring bike.

Specifications: 1993 Yamaha GTS1000

Engine: Transverse four-cylinder, chain-driven DOHC with five valves per cylinder. Liquid cooling. Bucket and shim valve adjustment. Wet sump lubrication.

Bore x stroke: 75.5 x 56mm

Capacity: 1002cc

Compression ratio: 10.8:1

Power: 74 kW at 9,000 rpm

Torque: 106 Nm at 6,500 rpm

Dry weight: 251kg

Seat height: 795mm

Wheelbase: 1495mm

Fuel capacity: 20l

Brakes: Front: Single 330mm Rear: single 250mm

Wheels/tyres: Front: 130/60 ZR17 Rear: 170/60 ZR17.

Front wheel travel: 116mm

Rear wheel travel: 130mm

Price: (NSW 1993) $21,500 + ORC