Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Bill Forsyth, Russell Colvin and Perspective Images.

In Historic Racing terms, it doesn’t get any better or bigger than The Goodwood Revival. What makes Goodwood unique is that the venue itself is as historic as the vehicles competing, and is presented in its finest light.

From the glistening white picket fences and replicas of the original grandstands that graced the 3.8 km track in its heyday from 1948-1966, the planter boxes full of colourful blooms, authentic signage and flags and numerous souvenir stalls, shops, cafes and other outlets dressed in period, this is a sight to be savoured. To maintain the authentic integrity, no modern vehicles are permitted within the circuit for the entire meeting.

Add seventy thousand fans, the vast majority wearing the fashions of the ‘fifties and ‘sixties, or military uniform to signify the venue’s original purpose when it was known as R.A.F. Westhampnett, and you have an atmosphere that, despite several rival attempts, cannot be replicated anywhere in the world.

And then, there are the vehicles. Hundreds of millions of dollars (sorry, pounds) worth of the rarest racing machinery in existence, all prepped and raring to go, with open exhausts not just encouraged, but required. So exclusive is this club, an invitation to compete in a car or on a motorcycle is highly prized and adds measurable value to the vehicle should it make the grid.

In the track’s original incarnation, before it ceased holding racing in 1966 (it continued as a testing venue for some years), Goodwood conducted just one motorcycle race meeting. This was back in 1951, on April 14th to be precise, when nine races were held in front of a crowd of 35,000. Star of the day was the pin-up boy of motorcycle racing, Geoff Duke on his works Nortons, who won both 350cc and 500cc races and set what was to remain the motorcycle lap record at an average of 89.1 mph. In the 400cc – 1,000cc race, in which Duke did not start, the win went to George Brown, the Vincent test rider, racer and sprinter, aboard a factory-prepared Black Lightning. Curiously, while the circuit’s fast, sweeping corners were well liked, some riders lamented the lack of the ‘blind’ corners so prevalent in pure road racing, and there were even suggestions to erect walls on the infield verges “in the interests of rider development”. This of course, failed to happen, and motorcycles played no further role for the next 47 years.

Then, in 1998, exactly fifty years to the day after the circuit first opened, the track was awakened from its slumber for the first Goodwood Revival meeting, which only came about after a prolonged legal battle between the circuit’s owner, the Earl of March, and numerous local resident groups in this frightfully silvertail area of Great Britain. Although the program was predominantly centred around cars, a motorcycle event was included, called the Lennox Cup and run over two legs for Pre-1966 (or thereabouts) bikes. There were some famous names in the field, including former World Formula One champion and ex-motorcycle racer Damon Hill, but the winner of both legs was Mick Hemmings on the ex-Jack Findlay McIntyre Matchless. In the audience for that seminal meeting was one Barry Sheene, who wasted no time in securing himself a ride for the 1999 Lennox Cup, which he duly won.

For the next four years, the Lennox Cup became an annual ding dong between Sheene and Wayne Gardner, and when the event was ne-named the Barry Sheene Memorial in 2003, Gardner continued as the outstanding rider, winning six consecutive events. Perhaps this domination had something to do with the decision in 2008 to instigate a second formula for the motorcycles, for bikes of a type produced up to 1954. Actually the Pre-1954 formula was in two sections; Group 1 for Up to December 1953 GP racing bikes, and Group 2 for up to December 1954 converted road bikes. The idea was that the formulae rotated, with the early class run in even-numbered years and the later formula in odd-numbered years. It made little difference for the inaugural Pre-1954 races held in 2008, because Gardner won again on a BSA Gold Star which reportedly stretched the interpretation of the rules somewhat. By this stage, the rules for the Barry Sheene Memorial Trophy had changed to stipulate two-rider teams on the one motorcycle, with a Le Mans start and a rider change midway through each race.

Food for thought

The Pre-1954 formula undoubtedly allows greater variety of machinery than the latter class which is dominated by Manx Nortons and Matchless G50s. This is a fact not lost on the Horner brothers, the men behind the fabulous Irving Vincents, built in the Horner’s state-of-the-art engineering facility in Melbourne. Ken and Barry have created a string a highly successful racers closely based on the original Vincent H.R.D. that have taken out prestigious events in Australia and at Daytona, USA, ridden by Craig McMartin and Beau Beaton. The Irving Vincents have been demonstrated at the mid-year Goodwood Festival of Speed, which is held not at the Goodwood race circuit, but within the spacious grounds of the Goodwood estate, and is the social event of the year for Historic buffs.

The Horners reckoned that a well prepared Vincent twin, in the basically original specification demanded by the Goodwood Revival rules, should be very competitive against the early model long stroke Manx Nortons and BMWs that form the pointy end of the field in the pre-1954 races, and a year or so ago, set about procuring a motorcycle for that very purpose. “A Vincent won at the only Goodwood motorcycle meeting in 1951, “ says Ken Horner, “so we thought it was high time a Vincent won again.”

That motorcycle is a 1948 Series B Vincent-H.R.D. Rapide, engine number F10AB/1/954 which the Horners acquired from long-time Vincent Owners Club member Bob Williams. Bob had owned the Rapide, which was originally sold by Sven Kallin in Adelaide, since 1991, and had ridden it in numerous rallies includingthe VOC International Rally in 1995 at Lake Taupo in New Zealand. This experience encouraged Bob to ship the Rapide to UK where he attended the 1999 International VOC Rally in the Isle of Man and Scotland.

The Horner’s preparation for the assault on the Barry Sheene Memorial Trophy at Goodwood in September 2014 was conducted with typical thoroughness. The Rapide was completely stripped and the engine meticulously prepared in-house using the knowledge gained from the Irving Vincent project. Goodwood rules stipulate such things as standard bore and stroke, so there was no opportunity for creative work there, but areas such as gas flow and internal lubrication (always a weak point with the Vincent twins) came in for much attention.

“We have learned a lot from the work we have done on the V8 Supercar engines for Garry Rogers,” says Ken. “After all, they are just 2-valve pushrod engines as well, so they have a lot in common with the Vincent”. A pair of new head castings came from Godden in England, but all the machining, including the combustion chamber, valve guides and posts, was done in-house. “The standard Vincent valves are too big, so we used smaller valves (1 9/16” inlet and 1 ¾” exhaust) to better suit the size of the ports, and the fact that under the Goodwood rules we were restricted to 1 3/16” carburettors and 100 octane fuel. The Amal Monobloc carbs came from Burlen Fuel Systems in England. We used the roller cam followers and cam profiles that we have developed for the Irving Vincents, and that makes quite a difference. We have a double speed oil pump and separate oilers to each camshaft to cure the lubrication problems that are inherent in the original design. When we put the engine on the dyno it just worked straight away – 98 horsepower; more than we had hoped for. We thought, ‘Wow, that’s a change, it’s usually the other way around!’”

The chassis also had to remain substantially standard, but the rear suspension was modified with an Öhlins shock absorber unit two inches longer than the original. As well as improving the rear end, this had the effect of steepening the head angle for much improved steering. The forks use the standard Vincent Girdraulic blades and top link, with a specially made lower link. It looks standard and correct, and that’s important to the boys. “We fully understand that Goodwood is a show and we wanted to play our part to the max,” says Ken. “We even had an old-style Exide battery case made with a modern battery inside”.

Track time

The completed machine was taken to Broadford where Beau Beaton reeled off a series of very quick laps with no major problems other than a woefully inadequate front brake, for which there was no immediate remedy. Into the crate it went, and the Rapide was soon winging its way back to the UK, from whence it had come 66 years previously.

The Goodwood Revival is always a fairly frantic affair, with practice and qualifying sessions and the races themselves scheduled down to the second, and the Barry Sheene Trophy bikes receive just one session where both riders have a very small window to come to grips with the lap itself and to sort out the bike. Although Beau Beaton had the experience of the short session at Broadford, co-rider Craig McMartin had never even sat on the bike before he was thrust into the qualifying session. It certainly was a baptism by fire, but Beaton managed to put the Vincent on pole position from ex-GP rider Jeremy McWilliams’ Manx Norton, with the BMW R5SS of Troy Corser in third.

The pace of the Vincent certainly raised a few eyebrows, as Ken Horner reflects. “John Surtees, who spent his early racing years on Vincents and worked at the factory, was in our pit all weekend and took a keen interest in the bike. He saw what we had done to make the front end work better, and he said that this is the way Vincent should have done it, except they had made the patterns and weren’t prepared to change anything.”

Saturday’s opening race saw McWilliams and Beaton hard at it at the head of the field until the Ulsterman threw the Norton away at the top end of the circuit, damaging the bike enough to put it out of the meeting. With the pressure off and the front brake virtually non-existent, Beaton continued steadily and handed the Vincent over to McMartin at half distance with a sizeable advantage. Craig was soon under fire from Glen English and Barry Sheene’s nephew Scott Smart, both on Nortons, but kept his cool to take the chequered flag ahead of English.

With the McWilliams/Fitchett long stroke Manx sidelined after Saturday’s crash, the organisers (with the consent of the motorcycle entrants) allowed the pair to substitute a late model Manx, although it was not fitted with a transponder and was ineligible for any official placing. For Sunday’s Race two, McMartin took the start (riders alternate the starting order for the two races) but was slow away from the Le Mans start and forced to give chase to the quick-starting Fitchett. There was nothing in it at the rider change, leaving Beaton to once again do battle with McWilliams. In a crowd-pleasing display of high speed dicing, the pair battled mightily but in the final few yards, and with the chequered flag in sight, the Vincent expired, momentarily locking the rear wheel and coasting across the finishing line in silence. Still, the overall win was claimed by the Horner team – a victory applauded with a standing ovation from the massive crowd.

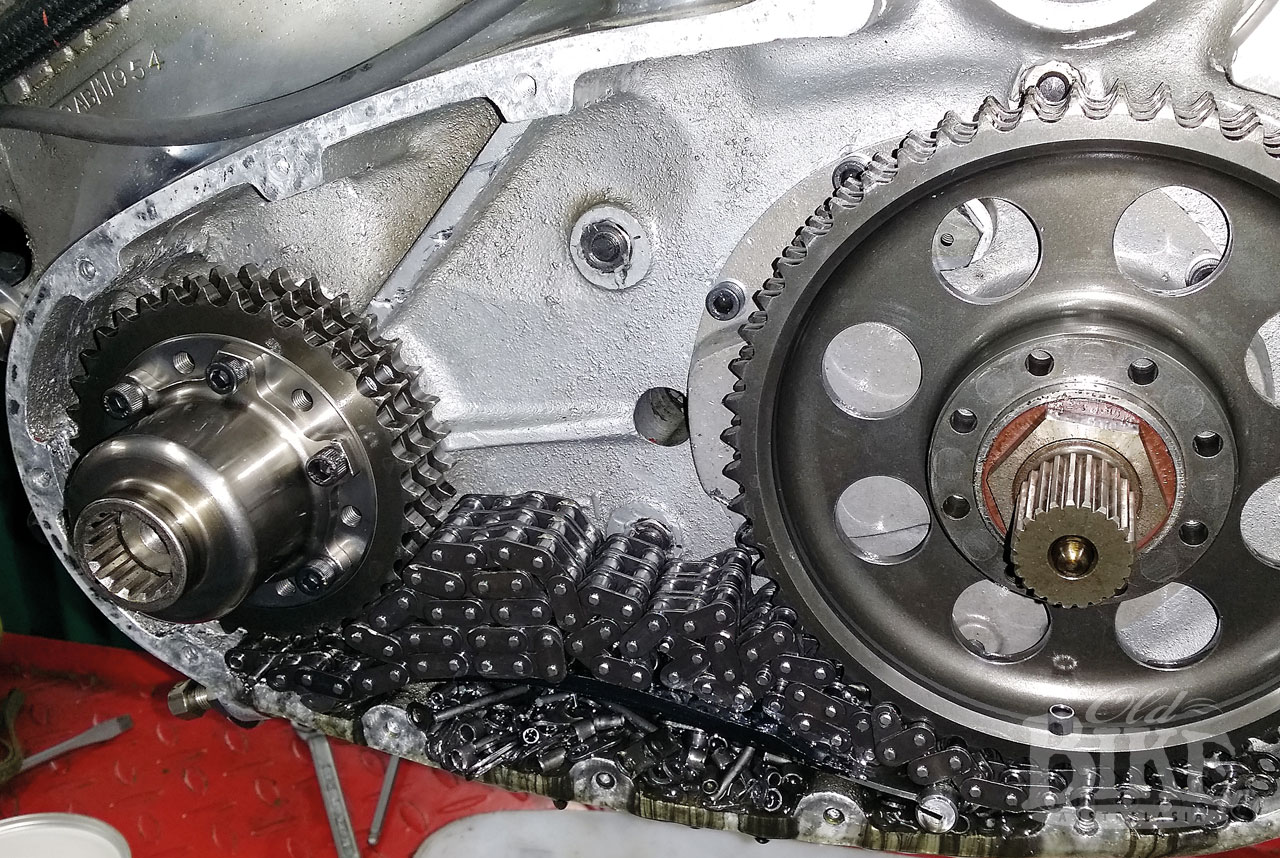

“We didn’t know what had gone wrong with the bike,” explained Ken Horner. “After we got it out of park ferme we just put it in the crate and went and had a bit of a celebration! It wasn’t until the bike arrived back in Melbourne that we had a chance to look at it, and it didn’t take long to see the problem. The primary chain had snapped. It’s a triplex chain, and although you used to be able to get racing quality triplex chain, these days that’s not the case – it is basically industrial chain and it just couldn’t cope with close to 100 horsepower.”

The team is already working on defending their trophy for the 2016 Goodwood Revival. “We definitely need better brakes – any brakes would be an improvement,” says Ken. “ We’ll check what the regulations stipulate and see what we can do in that department. Goodwood is not a heavy braking circuit like some of the shorter tracks, but it does have one corner (Woodcote) at the end of the back straight that is pretty hard on brakes. We reckon the bike is quick enough and handles well so with some brakes that should make quite a difference. We also want to swap the gear change and rear brake to the opposite sides. Both Craig and Beau are used to having the gear change on the left and it’s not a big job to swap them over. Obviously we have to find a solution to the primary chain problem too, but we believe we have that in hand. Belt drives are not permitted so it has to be a conventional chain of some sort. Our other bikes just run racing 520 chain and we’ve never had a problem. One thing’s for sure, we’ll be back for 2016, if we are invited, and with what we learned in 2014, we’ll be better prepared. ”

In the saddle (and occasionally out of it)

My chance to sample the Goodwood-winning machine came at the recent 2015 Penrite Broadford Bonanza. I have ridden plenty of Irving Vincents in the past – from the very first 1300 to the fuel-injected 1600, the Daytona winner, the current Period 5 bike, and the latest four-valve 1600 racer, but this machine is to all intents and purposes an original specification machine, albeit a beautifully prepared one. Instead of Goodwood’s flat, wide open spaces, the 2.2 km Broadford layout is tight, tricky and with a multitude of elevation changes, so it imposes an entirely different set of performance requirements.

The very first things I noticed when straddling the bike were (a) how high the seat was and (b) how hard the seat was. The reasons are inter-linked. Increasing the length of the twin rear shock absorbers by over 50mm jacks up the rear end (and correspondingly brings the rake of the front end back to 25 degrees), and permits the swinging arm to operate at a more optimum angle. But to keep the seat height as low as possible, something has to go, and that something is padding; the seat is little more than a vinyl covered plank. The footrests are also positioned high and quite rearward; a configuration that gives the old knees quite a workout.

Comfort aside, the Vincent is nevertheless meticulously crafted as a racetrack weapon, and once on the circuit the package immediately takes on its intended form and function. The suspension is taut, the ride and handling surprisingly sharp, but despite the flawless Horner engineering, this is still a 60 year-old motorcycle and nowhere is this more evident than in the braking department. The front brake – a twin sided, single leading shoe affair, is good for just one lap before it begins to complain audibly with a mournful howl when applied in earnest, which at Broadford is three times in each short lap. It is the major drawback in an otherwise superb package, but it is being specifically addressed and before the bike goes back to Goodwood for the 2016 Revival, new twin-leading shoe brake plates will be in service, along with better linings on slightly wider shoes. The primary chain issue has already been sorted out.

But despite the lack of retardation, the Vincent was a positive delight to ride, gobbling up both straights, and tracking precisely through the sweeps and swerves. In that respect at least, it is most unlike a standard specification machine. After one familiarisation session, I found, second time out, that I was able to ride a gear higher everywhere, and that lusty engine just revels in the task; the carburation spot-on. Although I scarcely looked at the rev counter, I know I was changing up well ahead of the 6,500 red line and simply enjoying the tremendous torque and the ultra-wide power band.

All too soon my stint came to an end, but I was left with nothing but admiration for the way in which the Horners have meticulously re-assessed the basic Vincent, employed subtle modifications without compromising the integrity of the machine nor the spirit of the Goodwood regulations, and turned out yet another beautifully crafted and presented motorcycle – the latest in what is now a long and illustrious line. No doubt there will be other, subtle tweaks before the Vincent goes back to Goodwood in September 2016.

What’s next? Well, there’s a very, very special 1300cc racing sidecar taking shape right now, and you shall read more of this soon…