There are more than 200 Australian motorcycle manufacturers scattered in the annals of history, stretching back to the earliest days of motorised transport, alas, now all gone. Perhaps the last was the Tilbrook, the work of a man with a remarkable mind.

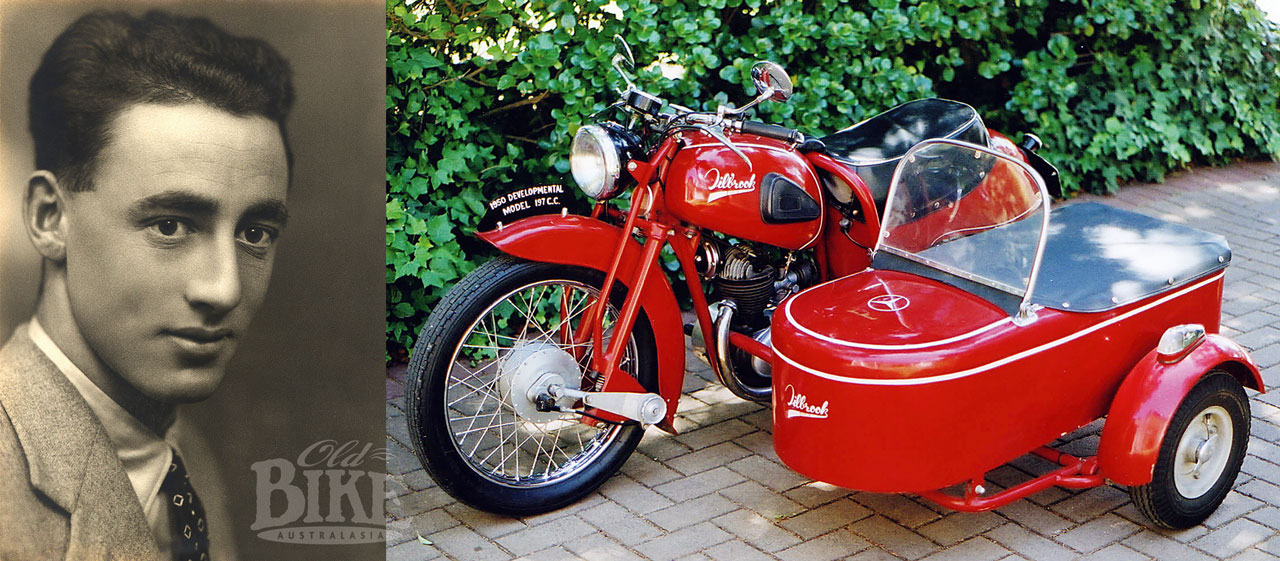

Rex Patterson Tilbrook was a man of relentless ambition. A gifted self-taught engineer, Rex’s probing mind was always searching for a better way; a more efficient means to manufacture; a breakthrough in design. Like many of his ilk, Rex could also be a prickly character when it suited him, and was the bane of many an over-zealous official whom he thought was being obstructive.

The Tilbrook clan arrived in South Australia from England in 1855. Within one generation, the name was synonymous with the emerging state, and not just in metal working trades. Henry Hammond Tilbrook (a cousin of Rex’s father) was a prominent amateur photographer, whose pioneering gelatine-silver work is now recognised as among the most significant records of the colony during the 1890s and early 1900s. One family went to Clare and branched into the print media while Rex’s grandfather eventually went to Yacca and blacksmithing, an essential trade that kept wheels turning, made picks and mining tools and was the forerunner of the heavy engineering that opened up the state. Rex’s brother began an eponymous brake and clutch service in Adelaide that was still trading into the 21st century. And young Rex of the inquiring mind, he just wanted to go motor racing.

Brooklands bound

Born in 1915, Rex was up to his elbows in engines from his early teens, and by the age of 16 had saved enough to acquire a very tired chain-driven Frazer Nash sports car that he set about restoring. He had visions of competing in the vehicle in local events, but quickly became focussed on a bigger picture. England, he reckoned, was the place for an aspiring young racing driver and engine designer to be. At the age of 18 he sold the car and booked a passage to Britain on a tramp steamer, arriving in early 1933 with high hopes of landing a job at the Fraser Nash factory at Brooklands in Surrey. With no such jobs on offer, he found employment at the neighbouring Hawker and Vickers aircraft factories which were also located within the massive Brooklands circuit – the heart of British motor sport.

The place was a hive of activity and manna for a wide-eyed young lad with motor racing in his veins. He soon befriended the owner of a Lea Francis racing car and struck a deal whereby he maintained the car in return for an occasional outing on the fearsome banked track. His fame as a mechanic and fabricator spread rapidly, to the point that he took a lease on a vacant building and opened his own workshop, making the specialised exhaust systems and silencers required by the stringent local noise regulations. Yes, noise was an issue, even way back then. His clientele included many top riders and drivers, among them the flamboyant Scottish rider, Fergus Anderson, and it was here he befriended an up and coming young rider on a Rudge, Dennis Minett, who went on to win two Brooklands Gold Stars riding Francis Beart’s Nortons.

Disaster struck in early 1938 when a broken acetylene gauge caused a fire that completely destroyed the workshop. Faced with the choice of rebuilding or bailing out, and with war clouds gathering, Rex chose the latter. With his Brooklands experience, he had plans of setting up in motorcycle manufacturing back in South Australia. Before sailing for home however, he travelled to several ‘continental circus’ race meetings with Fergus Anderson and other Brooklands associates before boarding a boat in Naples. After arriving home he was surprised to find that 22-year old Minett had followed him, arriving just in time to contest the Australian TT at Lobethal on December 26, 1938 riding the Norton that sidecar champion Bruce Rehn had won the Sidecar TT earlier in the day. Dennis had the 100-mile Senior in the bag until he was baulked by a lapped rider at the final corner, allowing George Hannaford on a Velocette to beat him to the line by a wheel. After this local motorcycle dealer Sven Kallin, the importer of German Zundapp machines, engaged Rex and Dennis to ride a 250cc model for promotional purposes to show its reliability. Unfortunately Dennis was involved in a near fatal collision with a bus while out testing and when he recovered sufficiently, returned to England and World War 2. Rex and a local rider Trevor Richardson continued with the undertaking and completed a record 10,000 trouble-free miles in ten days but it was all in vain as war broke out and trade with Germany ceased immediately. The record was never recognized by the Auto cycle Council of Australia because of some official technicality. With foresight Rex brought home six British motorcycles and an engineless Maserati racing car with the idea of selling them to fund a manufacturing business. Unfortunately the customs department confiscated the car to pay for duties so he was left with the bikes, one being a “Long Tom” Norton that was purchased by a very young Les Diener. This machine is still in South Australia having been restored by a meticulous enthusiast years ago and barely used since. Rex was able to rent a workshop at the South Coast town of Goolwa and set about manufacturing; one of his products being a very futuristic electric scooter that he began to demonstrate and attracted considerable interest but the out break of war put an end to these plans.

Hanging out the shingle

Back in Adelaide, Rex Tilbrook’s skills were utilised by the war effort in the munitions industry, but when peace returned Rex’s mind once again swung to making motorcycles. In a shed in the back yard of his home in the Adelaide suburb of Kensington Park, he produced the first in a long line of accessories – a universal pillion footrest. By 1947 business was ticking over sufficiently for him to expand to a proper workshop that he built in the same suburb, where he produced a greater range of motorcycle components as well as the first of the stunning Tilbrook sidecars. These unique creations featured a lightweight tubular chassis with torsion bar suspension carrying a stressed metal skin body mounted on tension springs. As well as the accessories and sidecars, Rex also constructed his own machinery, machine tools and workshop equipment. These included a drill press, arc welder, acetylene generator, mechanical and hydraulic presses, electro plating plant, enamel baking oven, air compressor, metal guillotine, tube roller, trip hammer, wheeling machine and numerous other ingenious pieces of equipment, the designs for which were either sketched on the back of old envelopes or on the floor with a piece of chalk.

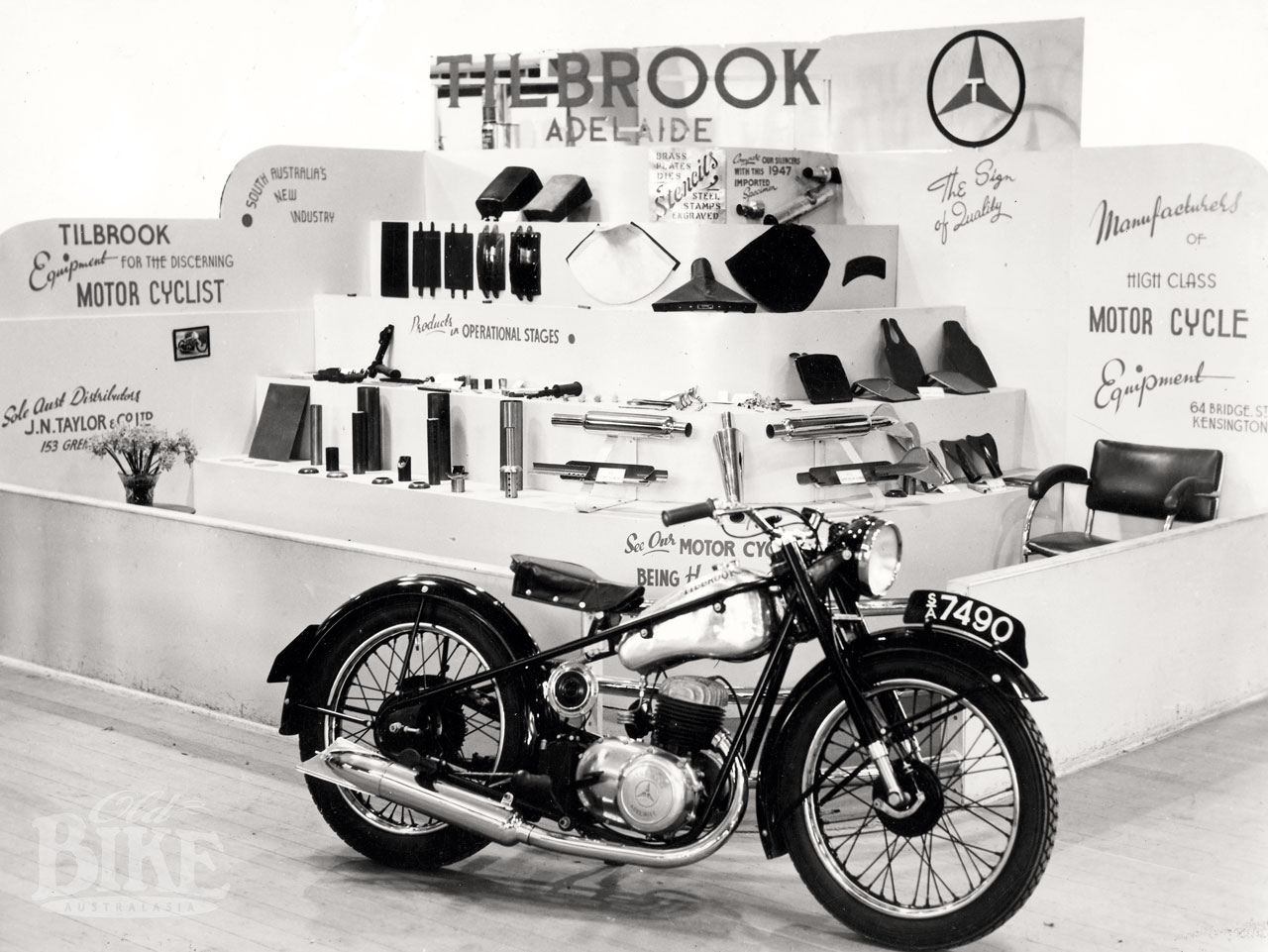

The dream of producing his own motorcycle still consumed Rex, and the 1947 Adelaide Exhibition, which ran from March 21st to May 17th, gave him the chance to do so. Rather than build a prototype in secret, Rex went public. He took a stand at the exhibition, set it up as an open workshop, and during the 54 days of the show’s duration, the first Tilbrook was constructed. The engine was based on a pre-war 250cc Zundapp, with castings made locally and machined on his stand. It featured an aluminium-alloy cylinder head with a flat-top piston, with a ten-port arrangement. The ignition coil, condenser, voltage regulator, cut-out and complete generator assembly were all housed in a neat compartment on the right hand side of the motor. The high-output 20-amp generator was designed to eliminate the major bugbear of coil-ignition systems by enabling the engine to be started with a flat battery. The crankshaft was supported by three main bearings with a white-metal big end bearing. Primary drive was by duplex chain to a three-speed gearbox with a positive-stop foot-change. Rex’s own design of pneumatic front forks which used air pressure to vary the travel, could be adjusted easily by bleeding or pumping more air into the units via caps on the tops of the fork tubes. In contrast to the usual brazed-up frames using heavy malleable lugs, the new Tilbrook’s chassis was all-welded, with the top tubes wrapped around the aluminium petrol tank in Coventry Eagle and Cotton style. Tilbrook claimed the only English parts in the entire motorcycle were the ball races and the primary and secondary chains. With the exception of these and the spark plug, the rest of the bike, including the ignition system was made in South Australia. The complete machine still exists in the hands of Rex’s family. Plans were announced for a production run beginning in 1948, with the option of rigid or sprung frames, but it soon became apparent that mass-producing the 250cc engine was a far more expensive proposition that had originally been thought. The Tilbrook factory was kept busy churning out its accessory range as well as the increasingly popular sidecars in their various styles.

In 1948, Rex convinced his old mate Fergus Anderson to undertake a trip ‘down under’ on a racing holiday. In typical fashion and at his own expense, Rex arranged everything; from organising entries at a string of race meetings, to public speaking engagements for the loquacious Scot, who brought with him a 250cc Moto Guzzi single, one of the first of the post-war 350cc 7R AJS racers, and a 500 wide-angle Guzzi V-twin. Far from being a walkover for the visitor, he was savaged by the local opposition at each appearance, although to be fair, the ‘circuits’ ranged from the public Woodside roads outside Adelaide, the narrow and bumpy roads through Victoria Park at Ballarat, and finally a gravel-strewn track of a wartime POW camp at Rowville near Melbourne. But Anderson conducted himself with aplomb, his many public addresses being received enthusiastically by the news-starved locals.

For local transport, Anderson also brought with him a gorgeous little 65cc Guzzi two-stroke, and for a spot of sight-seeing, set off in company with Rex, who rode a 1000 cc Vincent HRD loaned by an admiring enthusiast, for Melbourne – a journey of more than 500 miles over truly shocking roads. The little Guzzi never missed a beat and made a deep impression on Rex, who incorporated several of its design features into his own machines.

Before sailing for home, Anderson and Tilbrook travelled to Kingston in the South-East of South Australia to make attempts on the Australian land speed records. Rex constructed a special lightweight sidecar (to carry a passenger) that was fitted to Anderson’s machines, and also to the Vincent HRD ridden by local star Jack Prime. The result was a cluster of new records in various classes. In October 1949 Les Warton used another specially-constructed Tilbrook sidecar using a ballast instead of a passenger on his HRD to set a new mark of 122.24 mph, and with the Vincent in solo form, he averaged 139.8 mph.

Taking to the track

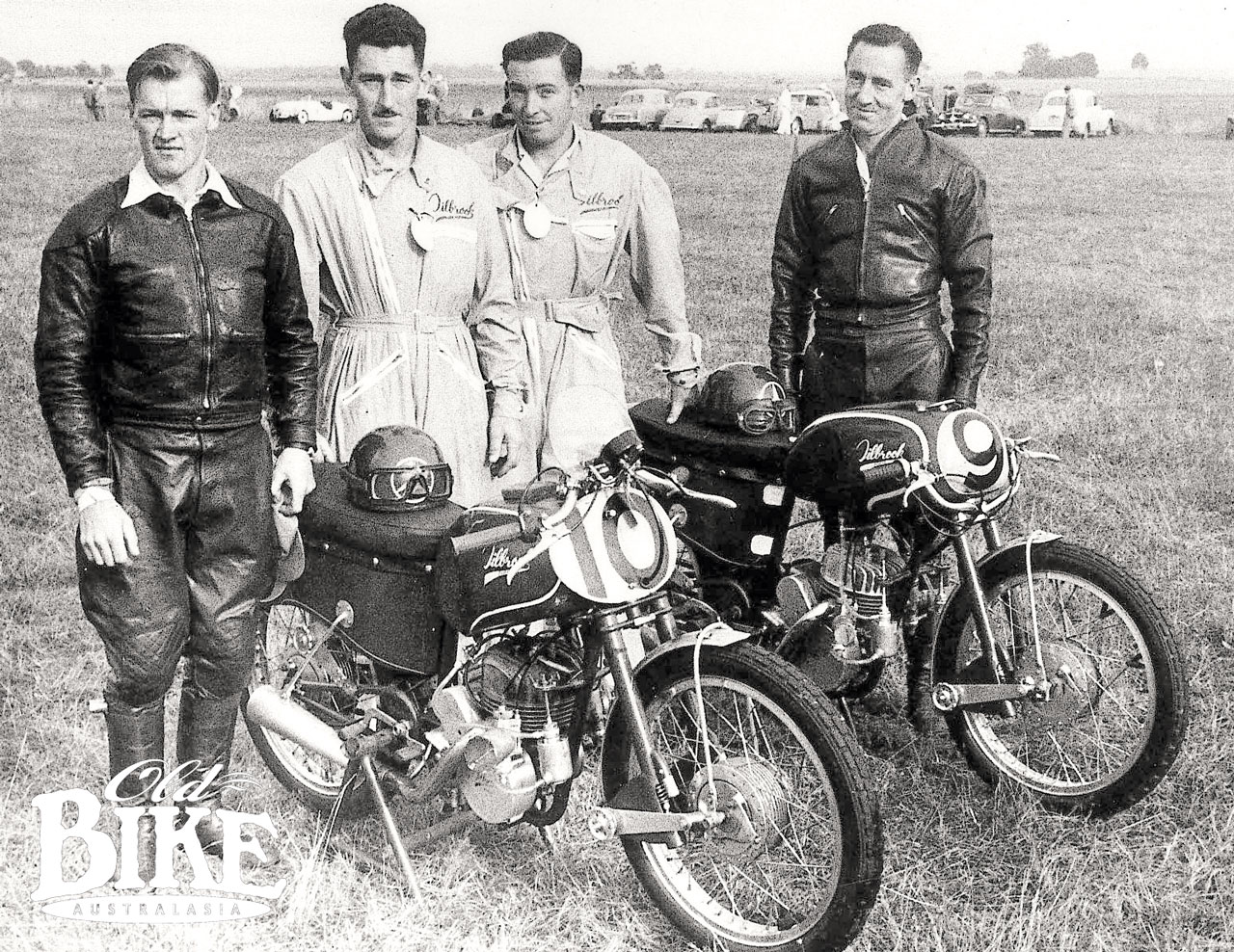

To showcase his growing range of products, Rex decided to build himself a racing 125cc machine, and three were constructed prior to 1950. Evidence of Guzzi design features could be seen in the racers, such as the radial arm front forks with friction dampers similar to that used on the ‘Gambalunga’ V-twin. The 125cc engines were originally 10D Villiers with minimum alterations, but were eventually highly modified with the barrel based on the pre-war Villiers Y-port design, with bore and stroke altered to 52 x 58mm. The methanol-fuelled power plant sported a two-staged induction system through Amal TT carburettors; the smaller one-inch unit opening fully at half throttle and the larger 1.187-inch unit taking over from there. Ignition came from a BTH magneto running at half engine speed, chain driven from the primary drive side on the left. The barrel featured two inlet, two exhaust and four transfer ports, with useful power between 5,500 and 8,400 rpm – good enough for a top speed of 90 mph. The single-loop frame sported Rex’s own design of cantilever suspension, with the spring units located beneath the 4-speed Tilbrook gearbox and damping by Andre-type friction units. The handsome alloy fuel tank doubled as a fairing/front number plate on Rex’s racer. Rex had a penchant for crouching as low as possible on the racing bikes, and devised a unique method of mounting the handlebars on the lower fork yolk. This system was not universally popular with the other riders, who preferred a more conventional set-up. The front forks had no conventional top yoke, with the tubular legs finishing at the bottom yoke. At race meetings, the immaculate red bikes were accompanied by mechanics dressed in pale blue Italian-style overalls, decorated with the Tilbrook logo.

The racers were ridden by a variety of noted competitors including multi Australian champion Maurie Quincey, who gave the marque its competition debut at Ballarat, on New Year’s Day 1949. Other regular riders included Rex himself, Tilbrook part-time employee and close friend Alan Wallis, and future multi ISDT gold medallist Tim Gibbes, who had one outing at a Ballarat meeting on 1st. January 1959 after Rex had retired. Tim recalled the occasion some years later.“ I drove across from Adelaide, and this proved to be an adventure in itself. My ‘race transporter’ was a Morris Oxford pickup, and I wasn’t far up the road when it lost a wheel. I patched this up but the wheel came off several more times until I welded it on with the brake removed. To make up time I drove as fast as possible – about 45 mph – which ran the big ends. That meant a strip down on the side of the road using the tongues of my leather shoes as big end shells! It worked and I made it just in time, but the race results weren’t all that brilliant.”

He actually finished 5th behind the other Tilbrook ridden by Alan Wallis in a fairly large field of regular 125 riders. The first 3 machines were all four stroke o.h.c. racers.

Production becomes a reality

With the racing team enjoying qualified success, Rex once again turned his attention to constructing a road motorcycle of his own design. In true style, Rex continuously leaked details of his ‘secret Australian motorcycle’ to the press to the point that a wave of enthusiastic publicity preceded the arrival of the first production model – chassis number 4 (1-2-3 were the 125 racers). For once, practicality had triumphed over passion, and Rex abandoned plans to produce his own engine. He imported a pair of German Ilo 125cc engines but future delivery could not be guaranteed so he opted for the ubiquitous 125cc 10D and 197cc 6E Villiers units. Apart from the engine and gearbox however, virtually everything else was produced in house – even the nuts and bolts and spokes.

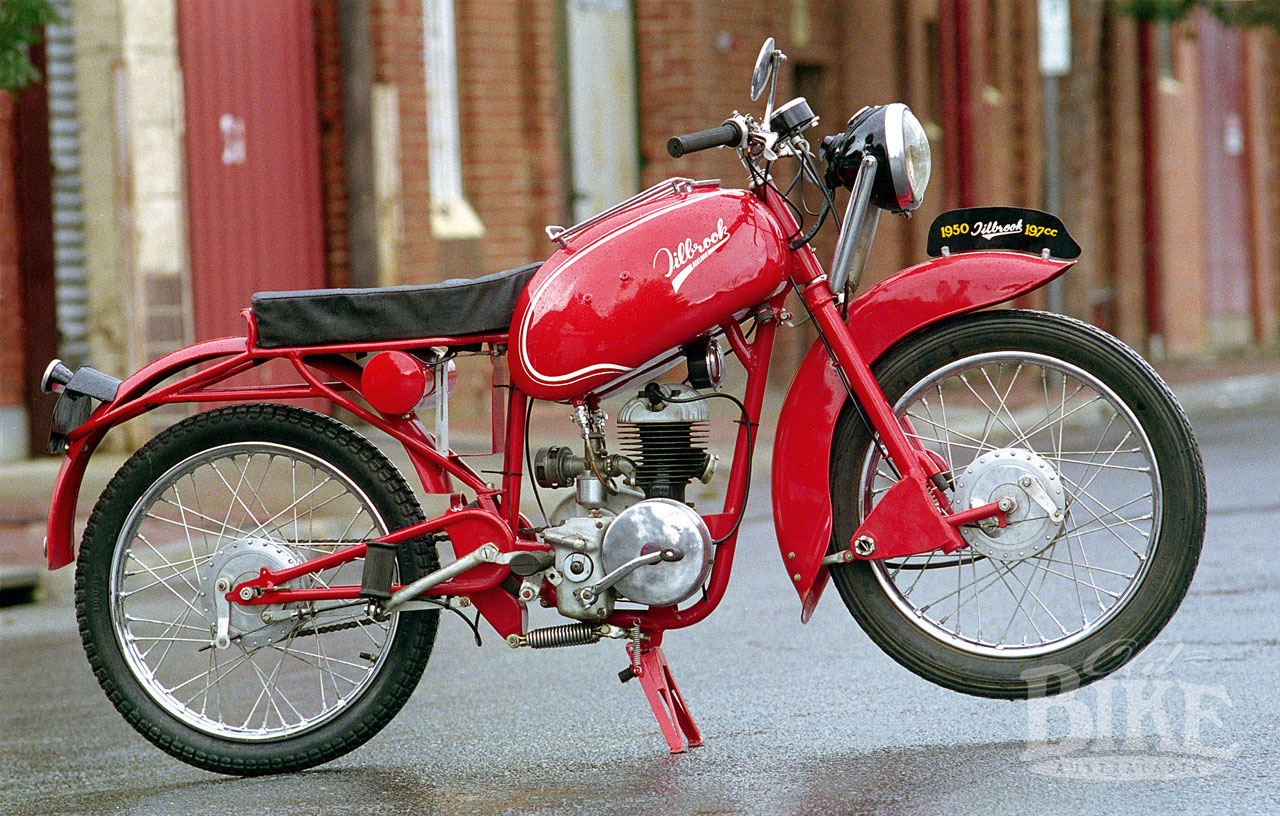

Inside the Tilbrook factory were individual sections for machining, fabric and leather trim, tube bending, plating and polishing and the paint shop which applied the lustrous deep red enamel that adorned all the solo motorcycles, with colours chosen by the customer for the sidecars. In August 1950, the first production roadster, a 197cc model, was handed over to proud owner Alan Wallis by the South Australian Minister for Roads, Sir Malcolm MacIntosh in a ceremony also attended by the Commissioner of Police and several federal parliamentarians. During the next five years, the machine covered 98,000 miles before being mothballed for 36 years. In 1991, Wallis restored the machine and still uses it regularly in vintage rallies.

The production Tilbrook featured an exceptionally large four-gallon petrol tank to allow for vast distances to be covered between fuel stops, and a large flared front mudguard to protect the rider from mud and road grime from the crude roads of the time. In contrast to the puny brakes fitted to most of the British Ultra-lightweights, the Tilbrook employed handsome and functional full-width finned aluminium hubs with shrunk-in cast iron lining and 37 mm width shoes. According to Alan Wallis, “The coefficient of friction of this combination was much greater than the normal practice of having the shoe lining working against a pressed steel drum and the greater heat generated under fierce braking was quickly and efficiently dissipated by the air cooled finned drums. Even under intense racing conditions there was never any hint of the brake fade that was so common with steel drums.

“All models had steering dampers, generally an optional extra on larger machines and virtually unavailable on smaller models, and all had chrome plated tank racks to protect the paint if the rider wished to carry a parcel or bag on the tank. It is worth remembering that motorcyclists of earlier years used their machines mostly to get to work and back, and many had to carry their work tools of trade as well as their lunch, so a kitbag on the tank was a common method of solving the problem.

“Whereas alternative lightweights had economy D-shaped speedometers, the Tilbrook was fitted with an 80 m.p.h. instrument having an odometer and trip meter mounted above the headlamp in an easy to read position. Under the press-stud fixed seat pad was a capacious compartment to house the battery, tool roll and puncture repair kit, as well as any spares the owner may have thought were necessary. The tool roll consisted of sufficient spanners to completely dismantle and reassemble the machine and included special tools made by the factory for the wheel nuts, swinging arm pivots, spark plug, exhaust pipe flange and head stem ball race lock ring. A tyre pump was provided and this fitted on spigots under the seat/mudguard assembly. Even the horn was an up market Lucas “Altette” model in contrast to the bulb air horn or cheap electric unit fitted to most British models under 250cc.

“Aluminum and bronze castings were supplied by a small foundry near the factory and footrest rubbers and seat inserts moulded by S.A. Rubber Mills (now Bridgestone) using dies made at the Tilbrook factory.”

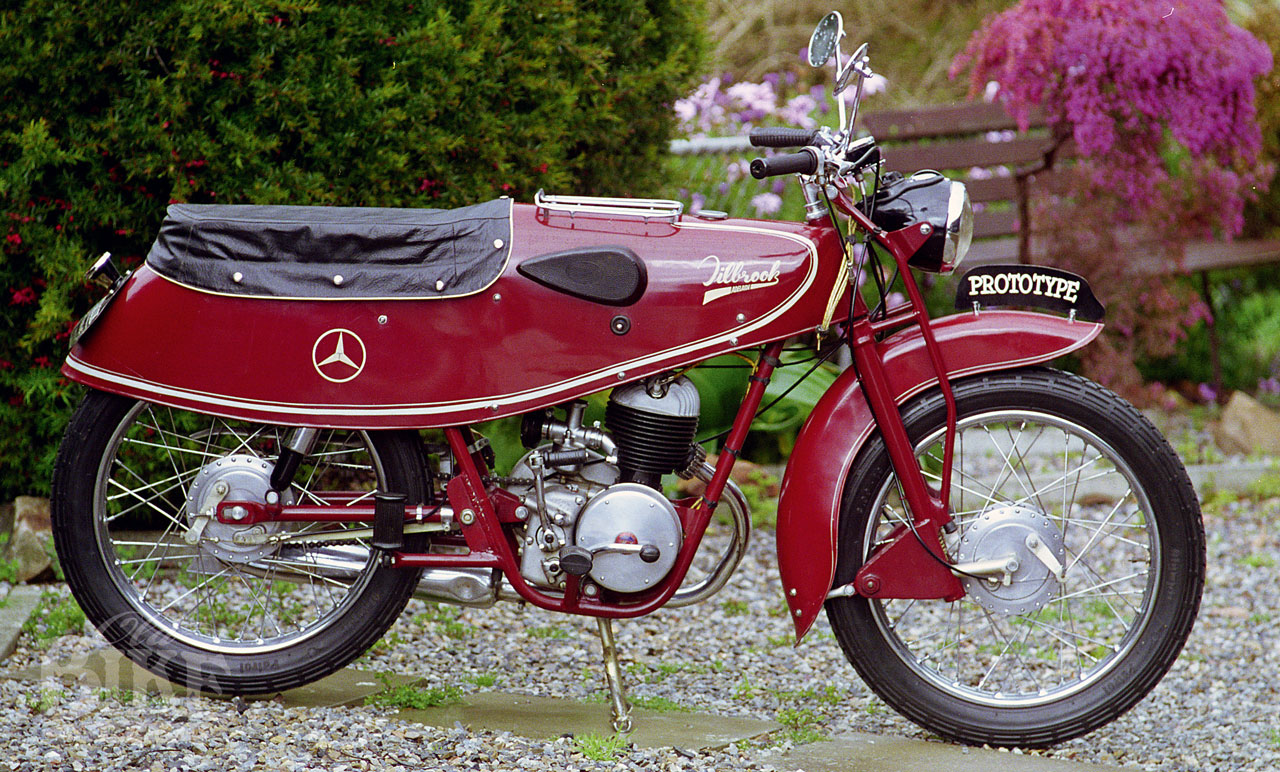

In all, around 55 complete road machines were constructed up till 1956, the final example being readied for the Royal Adelaide Show of that year. This version departed significantly from earlier models in that it featured a twin-loop frame with a conventional swinging arm rear suspension and Girling shock absorbers. The most striking feature was the all-enclosing bodywork which covered the petrol tank and carried the seat and battery/toolbox compartment. By this stage however, the motorcycle trade in Australia was in a seemingly terminal state and the new design never went into production. The prototype survived however and passed into the hands of noted restorer Ralph Datlan. It took Ralph years to persuade Rex to part with the machine, which had never been started.

This machine was fitted with a 10D motor as it was the only new motor in stock at the time although two later model egg shaped 197cc 9E units had been ordered but did not arrive in time. Ralph later fitted a 6E motor for better performance.

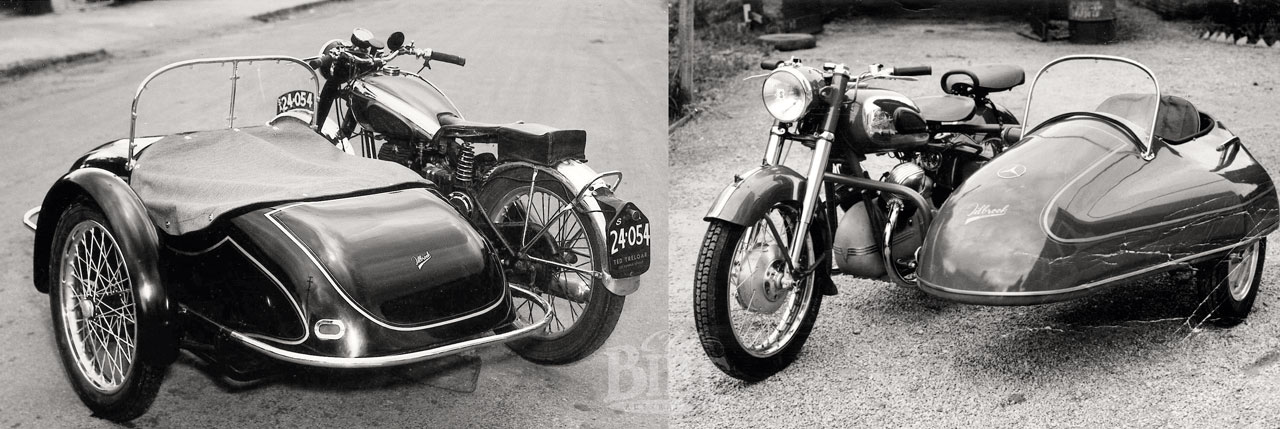

In reality, the motorcycle part of the business was minute compared to the sidecar production. 1,900 units were produced for both the home and export markets, ranging from the tiny 26 kg Tom Thumb version that was specially designed for lightweight motorcycles to the Dandaloo (aboriginal for ‘thing of grace’). This latter model was available as either a single or dual seater, with rubber bush mounting to insulate the sidecar from the vibrations of the motorcycle. Passengers enjoyed a plush ride, with the seat and backrest formed as a single unit, pivoted on rubber bushes and suspended on coil springs. Even after the closure of the engineering business in 1976, Rex continued to supply parts for sidecars, and even built the odd complete unit to special order.

Story Jim Scaysbrook with considerable input from Alan Wallis O.A.M.