Once the Depression was past, the 1930s were good times for motorcycle manufacturers, particularly in Germany where the big three: BMW, Zundapp and DKW, poured out a wide variety of machines that bristled with innovative features. Two young brothers, Wilhelm and Otto Maisch, eyed the booming scene with enthusiasm, and decided there was room for yet another brand. Thus Maico, an abbreviation of Maich Company (which was founded by Ulrich Maisch in Poltingen, near Stuttgart in 1926), was formed and began modest production in Wurtemburg in 1934, making their own frames and cycle parts with 98 cc Ilo and 125 cc Sachs engines. Successful as these two models quickly became, other factors, notably the intensified war effort, intervened to thwart Maico’s motorcycle plans, and production was switched to the manufacture of aircraft components. This required a move to larger premises in Pfäffingen-Tübingen, near Stuttgart where virtually the entire output went to the Luftwaffe, but the end of the war also signalled the end of the line for Maico’s aircraft business.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Sue Scaysbrook

The brothers now had a large factory (which had miraculously avoided much of the allied bombing), complete with tooling on their hands, so they did they only practical thing and returned to their roots; making motorcycles. This time they decided to build complete machines; their first power plant being a 150 cc two-stroke twin-port single which powered the Maico M150 of 1947. There was nothing particularly ground-breaking about the M150, which bore a passing resemblance to the DKW RT125, but it was a solid, reliable machine with brisk performance that set the company on the road to prosperity.

The M150 was soon upgraded to a full 250 cc and marketed as the M250, and to grab a share of the emerging scooter market, the company produced the Maico Mobil, followed by the Maicoletta in 1955. By normal scooter standards the electric-start Maicoletta was massive, with a steel body enveloping the rear section and the 250 cc engine that was soon punched out to 277 cc. Fourteen-inch wheels with full-sized drum brakes added to the bulky look, but even with 146 kg to haul, the Maicoletta was a spirited performer.

The M250, called the Blizzard from 1955, was soon joined by the company’s most radical creation, the Taifun (Typhoon), which first appeared as a 350 cc twin and soon became a 400. The Taifun owed little to its siblings, being virtually all-new, from the rear swinging arm suspension that bolted to the unit gearbox to the enclosed leading link forks, with the power and transmission unit used as a stressed member of the chassis. The Taifun, however is another story, and the company’s fortunes continued to rely upon sales of the comparatively conventional M175 ad M250, not just from civilians but from the German Federal Forces, which accounted for over 10,000 units.

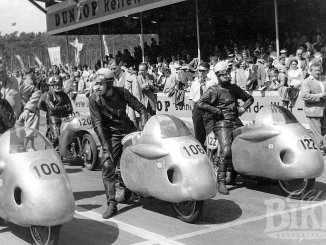

Early in the piece, Maico realised that competition was an ideal vehicle for publicity, and formed a race shop within the Pfaffingen factory, initially concentrating on the German scene where the 250 cc class was very popular. In 1957, the FIM instigated the 250 cc European Motocross Championship, and the title went to Maico works rider Fritz Betzelbacher on a scrambles version of the 250 Blizzard. Sydney scrambler Blair Harley brought back a 250 cc Maico Scrambler from Europe in 1959 that he sold to West Australian Alan Nicol, who went on to win the Australian 250 cc Championship in 1959. Queenslander Tony Edwards took out the Australian 250 cc Short Circuit title at Heit Park in the same year on a 250 Blizzard Scrambler.

Ironically, it was about this time that the factory began to suffer a number of setbacks, some to do with industrial strife and others of its own making, such as an abortive venture into car manufacturing. But to hark back a little, by 1956 Maico had established a solid range of road bikes that included 175, 200 and 250 cc road bikes, a 250 Enduro and Scrambler, the Blizzard 250 and Taifun 400 road bikes, and the Maicoletta scooter. The Whizzer Corporation in Michigan was appointed US distributor, while several models in the range were imported to Australia by Markwell Brothers in Brisbane and Milledge Brothers in Melbourne.

The M250 Blizzard, which formed the basis for the Enduro and Scrambler models as well, was a robust single-port two-stroke single pumping out an honest 18.2 hp, with a four-speed gearbox. The frame was comprised of both tubular and pressed steel sections, brazed and welded together, with conventional swinging arm suspension at the rear and BMW-style leading link suspension at the front controlled by spring/hydraulic units. A fully-enclosed rear chaincase kept things clean, and a neat aluminium shroud also enclosed the carburettor.

Despite the marketing efforts and the racing successes, Maico had its problems, and the company was drastically trimmed in the early 1960s, thereafter concentrating on off-road bikes almost exclusively. Sadly, the company collapsed in 1983, although the name and manufacturing rights were sold and have had several owners since. Maico is still being manufactured in Holland and the replicas of the 1980-81 model 250 and 490 motocross bikes are in high demand for classic motocross around the world.

Out of obscurity

Around 35 years ago, a locally-delivered 250 Maico Blizzard was pushed under a house in Brisbane and forgotten. It had covered just 23,000 miles from when it was sold new in February 1956, presumably by Markwells in Brisbane. In September 1971 it was sold to a Mr Laurie of Clontarf, Brisbane and from there the trail goes cold.

When I discovered the bike it was covered it a thick layer of grime accumulated in its dark slumber. Fortunately, the environment was fairly dry, so corrosion was minimal. From the look of it, I doubt that it had ever had the luxury of a de-grease; everything from the steering head back covered in a thick, baked-on residue of two-stroke petrol/oil mixture, road grime and grease. Although this layer was a nightmare to remove, at least it had good preservative qualities. Looking past the crud, what impressed me was that the Maico was totally original, down to the pressed-metal ‘Blizzard’ badge on the rear mudguard. That mudguard was somewhat the worse for wear, having been rear-ended at some stage which cracked the beading when it was pushed in. The front guard also had a few dings and ragged edges, but both were salvageable.

From a design aspect, the bike is an interesting farrago of components. On one hand, the engine, although of conventional two-stroke piston-port specification, is a very good performer, as evidenced by the success of the bike in off-road trim. A Bing 26 mm carburettor (with what Maico call a starting device – a choke slide) is fitted, along with a small wet-element air filter, but it is secreted away behind and very a neat shroud constructed from cast alloy in two halves and crewed together. It’s complex, but it keeps the carburettor, with its inherent petrol-oil diet and associated goop, out of sight, providing a clean exterior, at least in theory. The four-speed gearbox and multi-plate clutch both run in an oil-bath, with a 3/8” x 3/8” 54-link primary chain. A neat touch is a gear-position indicator that exits on the top of the gearbox casing and is connected via a Bowden cable to the speedo, which incorporates a tumbler with a different coloured display for each gear.

But the powerplant is burdened by an incredibly heavy suit of clothes; both mudguards are massive in size and construction, and the frame itself is no lightweight. The twin toolboxes, also in heavy gauge steel, look capable of holding a complete set of clothes and enough spares to rebuild the bike. The seat is similarly huge and would not be out of place on a bike three times the capacity; indeed it bears more than a passing resemblance to BMW seats of the period – must be a German thing. Up front is a set of leading-link forks that could take on the roughest terrain, and with the Blizzard in motocross trim, did. The trade-off (over the use of a conventional telescopic fork) of course is more weight, lots more. Front-end movement is controlled by a pair of Hemscheidt spring/damper units which are also significantly different from British-style components in that there are no collets to secure the springs and covers. The top, chromed-plated cover screws onto the top alloy forging, and when removed, exposes a soft pin that can be driven out to allow the unit to be dismantled, while the bottom section containing the damper body and bottom mount is a single casting. Unusual, but stylish and effective.

At the opposite end of the scale are the wheels, which are incredibly light. Maico’s own hubs are used, virtually identical front and back; the rear hub with a cush-drive with seven rubber segments. The brake drums measure 160 mm diameter with 30 mm wide shoes. The hubs are laced to German Altenburger alloy rims that are a really unusual design with flat sides. These rims were the product of Karl Altenburger, a professional cyclist of the 1930s, who also made bicycle rims, levers, brakes and derailleurs. It strikes to me that Maico, in its 1950s form, was very skilled in pattern making and aluminium-alloy casting. As well as the hubs and their robust (especially the rear) backing plates, such ornate castings are also to be found on the rear mudguard brackets and especially the top steering crown, which is a work of art. The cables pass through slots in the crown, which is capped by an ornate steering damper knob, also cast alloy, with the Maico badge inset.

Whereas British bikes of the time, especially the two-stroke lightweights, shared many proprietary items, the Maico is almost entirely bespoke. Certainly, there are the expected sourced items such as Magura controls, including the ornate twistgrip that invisibly pulls the throttle through the inside of the right handlebar. The handlebars are split in two; each half clamped into the top steering crown.

The resurrection

Once the Blizzard had been extracted from its cave and transported to Sydney, I simply stored the bike while the availability of spares and knowledge was assessed. Fortunately, there is a small but strong group of Blizzard enthusiasts, notably Günter Oehlmayer in Bottrop, Germany, who knows the model inside out and holds a large stock of spare parts. Once confident that the machine could in fact be restored without excessive grief, I took the plunge to pull it apart. The bike came with its original owners handbook, which was a great help, but even better, John Finglas in Brisbane sent me a genuine ex-Markwells Spare Parts list, which has exploded views of all components and the part numbers.

As always, before a spanner was laid upon the machine, it was photographed from nose to tail, including such things as the wiring harness connections and anything that was likely to be confusing in the reassembly. The process of dismantling the little Maico, clustered in crud that had built up over a period of over 50 years, was a messy and laborious task. Some of the gunk was so entrenched it had to removed with a hammer and chisel. But finally it was apart and clean enough for the paintwork to be dispatched to Andrew Price in Melbourne (0407 049767). This is a bike with a lot of paintwork – virtually nothing is plated – and one decision I made was to ditch the original décor – a muddy and unattractive shade of maroon – for the silver blue finish used on the 400 Typhun. The fuel tank originally had painted panels over chrome plating, but I opted for a fully-painted finish because the original chrome was badly pitted and the tank had several small dents. It would have been an expensive process even if the tank could have been re-chromed, and anyway, the Blizzard was available in several other hues without a chrome tank – black, blue and the maroon, always with gold striping on the tank, toolboxes, mudguards and front forks. As well as the paintwork Andrew undertook the repairs necessary on both the rear and front mudguards.

The next step was to send the wheels to Ash’s Spoked Wheels in Brisbane, where they were vapour-blasted, new spokes and bearings fitted, and those rare Altenburger rims polished to a mirror finish. Ash’s did a fabulous job and I always believe that wheels maketh the bike when it comes to a restoration. A rear German Hidenau tyre of the correct block-style pattern came from Bruce Collins in Melbourne, and the front 300 x 18 Metzeler Block C from David Howe’s private stock in Richmond, NSW. The seat went to Broadford Motor Trimmers in Victoria, who also did a terrific job that included rescuing the aluminium moulding that runs around the base, recovering in the correct style of vinyl, and remaking the rather quaint strap that must double as a passenger grip.

Most of the parts simply needed refurbishment but there were a few that had to be replaced. These included the headlight rim, brake shoes, the components for the rear hub cush drive, footrest, kick start, handlebar and gear lever rubbers, the rubber surround for the toolbox lids that seals the compartment and a few small electrical items which all came from Gunter Oehlmayer. A handlebar with the correct slot for the Magura twistgrip came from Motorrad Meister in Germany, while Mark Huggett in Switzerland (www.bmwbike.com) supplied a vital component – a set of tapered roller steering head bearings. As fitted, the Maico used the old style cups cones and ball races which were not only completely worn out but unprocurable. The bearings supplied by Mark have been specially manufactured to suit early BMWs such as the R51 series, because there is no catalogue bearing in this 51 mm x 34 mm size. They are slightly thicker (12 mm) than the bearings originally used in the Maico but still fit OK and are a great improvement over the originals.

The speedo is a complex little gadget that incorporates the gear selection indicator, which is actually not yet fitted pending the making or procurement of a suitable cable. The instrument was refurbished by Peter Boros (02 9920 6658) who bought a very tired looking gadget back to as-new. What little plating there was went to Pioneer Plating in Sydney (02 9734 6609), who luckily were able to rescue the very badly pitted chrome caps for the front forks as new replacements were not available anywhere.

While waiting for the various specialists to work their magic, I was able to get on with other processes such as polishing the alloy castings, sourcing stainless fasteners (metric, so readily available), and getting the shock absorbers into working condition. The rear shocks were actually OK, seeming to have adequate damping and needing only a revamp that included polishing the alloy covers. The front shock however were a different story as one had a blown seal and a slightly bent shaft and these were dispatched to my brother Peter at his engineering business in Taren Point, Sydney (0425 216911), for expert attention. Peter also tackled the extremely vexing (for me) issue of re-wiring the bike, as the original harness was an evil looking tangle that was basically beyond saving.

A new exhaust header pipe was sourced from Germany but a new muffler seemed not to exist for the earlier Blizzards, which had the muffler mounted on the left, so the rather ratty original was given to exhaust pipe specialist Phil O’Brien (02 9521 5637) who dismantled the pipe, removed an enormous amount of built-up crud, welded in new sections and had the lot re-chromed by Pioneer Plating.

The result is, I think, rather stunning, particularly given the ghastly state in which it arrived. The little Maico is a real head-turner – most people being completely unaware of the marque. It goes quite well too; not in the Bultaco Metralla league, but certainly quicker than, shall we say, a Francis Barnett Plover!