In the Great List of outstanding motorcycles, there is but a handful worthy of the title of Ground Breaking. In the late 1960s, it seemed the world motorcycle industry, European, American and Japanese, was entirely focussed on bigger and better road burners.

It was the era of the Honda CB750, the Norton Commando, the BSA/Triumph triples, Kawasaki H1… tar scorchers all. But at the Tokyo Motorcycle Show of October, 1967, Yamaha blew the socks off them all, not with a multi-cylinder strip-scorcher, but with a humble-spec, single cylinder two stroke – the DT1. This machine not so much as filled a category, but created one – the first true dual-purpose on/off-roader that really worked. Up till then, the choice had been basically down to tricked up or dumbed down motocrossers like the Bultaco Matador, Montesa King Scorpion, Ossa Pioneer, Ducati Scrambler, and a few fairly nasty British models that had a foot in the trials camp as well. Then along came the DT1.

A certain amount of credit for the creation of the DT1 must go to the American Yamaha dealers and importers. It was they who continued to clamour for a dirt bike that could be ridden on the road. For the Japanese, this was difficult to understand. Off-road riding meant racing, because trails and dirt roads didn’t exist in Japan, nor, to a large extent, in Europe. There was no such thing as a non-racing, leisure riding off-road market, but the Yanks were insistent. Pointing to the fact that the biggest sellers of the European markets mentioned above were in fact dual-purpose models. Impending legislation however, was to have a big impact on the Spanish models. Strict silencing laws, and a requirement, at least in the huge Californian market, for the bike’s light to operate without the engine running, posed serious problems for these manufacturers. But not for Yamaha.

Never has the old adage ‘If it looks right, it probably is right” been more completely fulfilled. From every angle, the DT1 fitted the bill, and yet its specification was, at least on paper, nothing to get overly excited about. The engine was a simple, piston port 246 cc two-stroke single, developing a modest but honest 22 horsepower at 6,000 rpm, breathing through a 26 mm Mikuni carburettor, with a five-speed gearbox. But unlike all the aforementioned ‘competition’, the DT1’s engine featured Yamaha’s own Autolube oil injection, which did away with the old two stroke bugbear of mixing oil and fuel manually. Not only was this far more convenient and cleaner, it reduced the typical two-stroke smoke haze because the amount of oil injected was controlled by the throttle opening. Another point of difference was in the electrics – reliable sparks, plus lighting (including indicators) that actually worked, and kept working, plus a speedo and tacho that were accurate and even looked the part. The DT1’s electric department sported twin coils, meaning that the battery could be removed for competition work. Yamaha’s five-port system had been used on the racing TD1 models with increasing success, and it was also adopted for the DT1 – using two additional small ports which greatly helped the scavenge cycle in forcing burned gasses from the cylinder.

The gearbox incorporated five well-spaced ratios with a delightfully slick change, although it was subsequently found that with use the selector throw could get slightly out of whack. Fortunately the adjustment was both simple and effective. At the time of the DT1’s release, the majority of riders had been brought up with British-style right foot gear change, so the DT1’s gearbox had the shaft running right through and out both sides, so the gear lever could be easily swapped, as could the rear brake pedal, although not quite so easily.

The DT1’s frame was not exactly earth shattering either, but it was unlike anything that had previously come out of Japan. The conventional twin loop tubular chrome moly steel frame had a single top tube and a fabricated, rectangular section swinging arm at the rear. Up front were Ceriani look-alike telescopic forks, which actually worked remarkably well and offered a respectable 150 mm of travel. Even the all-chrome rear shocks operated satisfactorily, at least when new. The seat was wide and comfortable, the handlebars high, (perhaps a little too high) wide and handsome. Much attention had been paid to making the package as sleek as possible. The engine was commendably narrow and the exhaust system carefully moulded to tuck, as did the kick starter. Wheels and brakes were also conventional; a 400 x 18 at the rear, and a 3.25 x 19 up front both shod with Trials Universal tyres, and polished alloy, full width hub brakes that did all was needed.

In similarly muted fashion, the fuel tank was finished in white with a subtle metallic flake and black lines with red Yamaha badges, while just about everything else was silver grey; mudguards, fork legs, headlight brackets and numerous small fittings.

When the DT1 hit Australia in early 1968 it created not so much a sales rush as a positive stampede. In New South Wales, the Yamaha importation was in the process of switching from long-established Tom Byrne (who jumped ship to handle Kawasaki) to the US McCulloch company. Byrne’s received the first batch of DT1 in Sydney (which were not fitted with traffic indicators) but all subsequent shipments came through McCulloch. That first batch were full-spec US models, hence the lack of indicators and also tachos. McCulloch’s first shipment had twin instruments, although the tacho was much smaller in diameter than the speedo. Both had rubber rings fitted to protect the rims.

On the road, the DT1 would top out at 70 mph (112 km/h) which was still plenty fast enough to get you to and from the trails on the weekend. The wide speed of power meant the bike was brilliant in traffic as well as off-road.

So if this bike was so average in specification, why all the fuss? Well, in this innocent period, the outer urban areas of Australian capital cities were still mainly bush, with miles of fire trails and gravel roads just crying out to be monstered by the new breed of dirt jockey. And after a weekend of fun in the scrub, this machine could be ridden to work as well with no more than a change of tyre pressures. And all for $657.50.

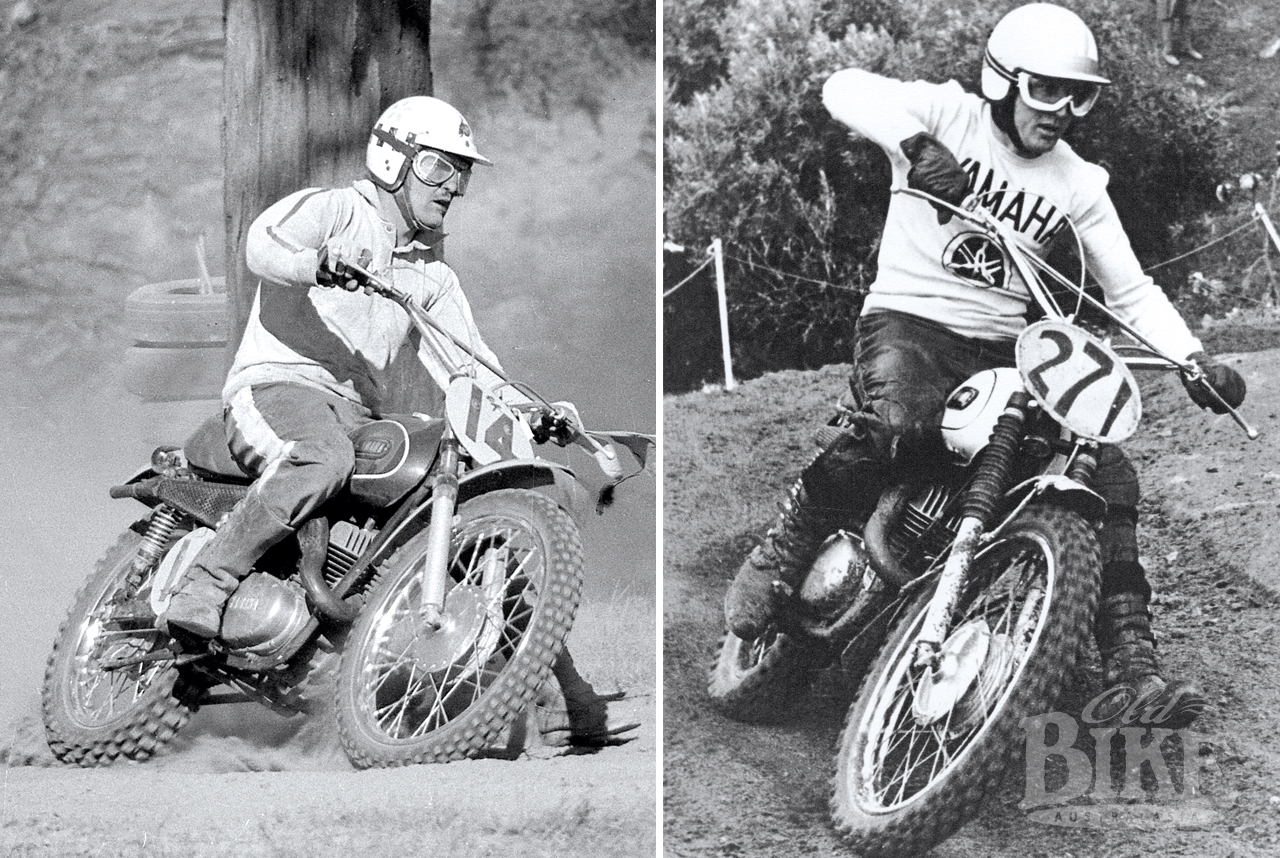

It took very little time to realise that the DT1 was also a surprisingly effective motocross tool, even in standard specification, and with the addition of the factory GYT (Genuine Yamaha Tuning) kit, it became a serious contender in the booming 250 cc class. The kit consisted of a cylinder barrel with a chrome-on-alloy bore to replace the iron-liner standard job, a central-plug head, single ring instead of two-ring piston, 30 mm carburettor and expansion chamber exhaust pipe, which added another 8 horsepower instantly. There was also a slightly different air box but the standard one could be similarly modified with slightly larger inlet holes. The kit contained a range of sprockets and an optional 21-inch front wheel also catalogued. At just $140, the kit represented exceptional value.

Indirectly, the DT1 was a major shot in the arm for the sport of motocross itself, as it provided a true and competitive dual purpose machine to rival the dedicated ‘crossers from CZ, Husqvarna, Greeves, Bultaco and Maico, to name just a few. As a measure of just how competitive the DT1 was, South Australian Bob Voumard to a virtually standard DT1 to victory in the 1968 250 cc Australian Scrambles Championship held at Collie, WA – Yamaha’s first off-road title in this country. From that point on, the model won motocross titles in virtually every state, and all-rounder Dave Basham even took a SA road racing title on his with just a change of tyres.

The DT1’s soaring popularity virtually created a new after-market industry overnight. Plastic mudguards, unbreakable levers, front fork damping and spring kits, a plethora of rear shock absorber options, alloy rims and seat bases, plus all manner of engine mods flooded the market. One of the first items usually replaced were the spring-loaded footrests with their fat rubbers which became as slippery as an eel when covered in mud. To save the owner the trouble of converting his own DT1 for serious track work, Yamaha produced the DT1 MX, along with a big brother in the form of the 360 cc RT1 MX. These were even closer to the original DT1 concept and shared the majority of the major components.

Yamaha itself was quick to realise the potential of the DT1 as a serious motocrosser, particularly with input from the likes of Don and Gary Jones in the USA and the Dutch -based European division. The works bikes and the limited production YZs were increasingly tricky (and increasingly effective) pieces of work, but had clearly evolved from the DT1.

Until the adoption of the cantilever frame, subsequent models of the DT1 line differed little from the original pearly white version in anything other than décor. The front indicators were moved from the headlight brackets, where they caused frequent carnage whenever the bike was dropped on the trails, to the handlebars, and the swinging arm became a conventional round-section. Before long the range had been expanded to include the 125 cc AT1 and the 175 cc CT1, then big brother in the handsome black and red 360 cc RT1.

Predictably, after being caught seriously napping, Yamaha’s competitors, initially Suzuki and Kawasaki and later Honda, scabbled to the drawing boards to pen their own versions, and by and large, failed, at least in the first attempts. The Suzuki Savage proved to be very aptly named, with none of the grace and sophistication of the DT1, while the Kawasaki F4, with its portly disc-valve engine, was a complete failure that sold like kittens. It wasn’t until nearly five years later that Honda came up with anything like a competitive option of its own, the four-valve XL250, but by then the whole trail-riding boom had become a victim of its own popularity.

As the swarms of trail bikes infested the hills on any weekend, scaring the living daylights out of horse riders and bush walkers, so the authorities began to plot and scheme against them, to the point of enlisting police and rangers, also on trail bikes, with new and far-reaching powers. The conservationists were also up in arms as the bikes carved giant erosive ruts in the topsoil. Serious injuries, including fatal head-on collisions, became quite commonplace, as did the chest-beating media reports. More than a few booby traps were set by the more militant tree-hugging types, resulting in more deaths and serious injuries, which only added to the media beat up. In short, the urban trail riding bubble burst as quickly as it had formed. In its wake came the enduro boom, which brought a degree of organization to the normal weekend carve up, along with vastly more sophisticated machinery. But endures were a far cry from the concept of jumping on your DT1 and disappearing into the nearest piece of bush for a few hours – the convenience factor was gone for good. In the USA, where it all started, things were even more serious, with draconian legislation, which differed state by state, accelerating the demise of trail riding as a leisure pastime and forcing bikes into dedicated ‘trail parks’ and other controlled situations.

But it was great while it lasted, and it all stated with the DT1; arguably the most influential bike ever to come out of Japan.

A birthday present

When Yamaha celebrated its 50th anniversary of motorcycle manufacturing in (year), Sydney identity Mark Firkin had an idea. In his collection of off-road machinery, which contains some really rare and unusual stuff, he had a Yamaha DT1 with a very significant history.

“The DT1 was owned by Geoff Eldridge (journalist, serious dirt racer and founder of Australasian Dirt Bike magazine), who was a great mate of mine,” says Mark. “I had a DT1 as well that I used to race – it was known as the DT1 From Hell – and Geoff said he would restore his to original specification if I did mine up as a GYT kit bike. But then Geoff was killed in USA, so it never happened. His DT1 was hanging on the wall of the ADB office in Warriewood (northern Sydney), but with Geoff gone his widow Vicki decided to auction most of the collection. Ray Ryan (founder of VMX magazine) bought it, with the intention of restoring it, but poor old Ray did not live long enough to do it. Ray’s widow Barbara thought I should have it, so the DT1 has gone the full circle.”

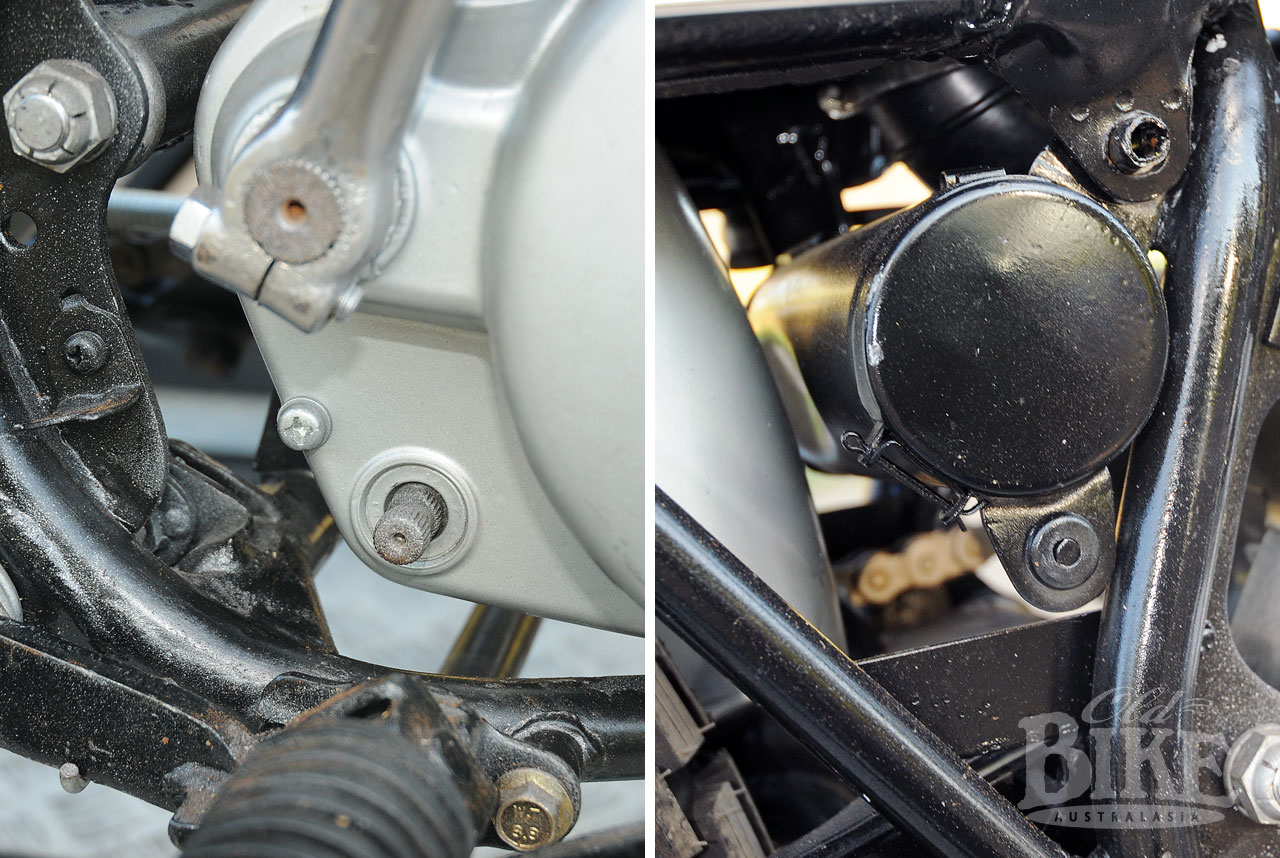

“When the Yamaha anniversary came about, a journalist contacted me and said he had heard I had a DT1 and could he do a story on it as a milestone in Yamaha’s history. I told him that the bike wasn’t exactly pristine, but Yamaha put a few dollars up and so I restored it, and Yamaha took it to shows all over the country in their birthday year,” Mark recounts. The restoration included a pair of new old stock rear shock absorbers bought on eBay for $40. “They actually work quite well,” says Mark, “but the seals usually blow out fairly quickly. The tank badges are original, but replica replacements can be had for around $100”.

One sunny day in May we ran the camera over Mark’s restored DT1, which hasn’t been fired up for a number of years. It certainly took me back to the days in the late 1960s when it seemed everyone had a DT1. I recall the car park at the Anzac Memorial Hall in North Sydney where Willoughby District Motor Cycle Club used to hold their monthly meetings, and I clearly remember counting 28 DT1s there, including mine, on one evening, in an era when the meetings would draw up to 300 people. Without this landmark machine, things would certainly have been different.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook • Historical photos: Greg Heath