Show any motor racing enthusiast a set of roads that form a lap and the wheels start turning – literally and figuratively. In the days when Australia had no racing circuits built solely for that purpose, the best prospective speedsters could hope for was suitable streets that could be borrowed every now and then, and the cooperation of the relevant authorities to enable their use. Sometime the former was a lot easier to achieve than the latter. New South Wales had a particularly strident approach to such road closures, in fact, the police force, with whom the ultimate jurisdiction rested, were violently opposed to just about any motorised contest, be it speedway or circuit racing.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Paul Hanke, Alec Fisher, John Shanks.

As far back as 1938, certain motor car racing types had been casting an eye over the rather interesting network of roads that ran inside the grounds of Parramatta Park – literally the birthplace of the nation and home to the two oldest buildings in Australia; Old Government House and the Dairy Cottage, and in the heart of the city’s booming western suburbs. Over time the roads were sealed and offered a variety of configurations, none ideal for racing, but at this point in time no-one was particularly choosey.

Much groundwork was done, much lobbying of local government officials took place, publicity on the benefits to the community generated, but the final hurdle remained. With hardly a moment’s hesitation, the Commissioner of Police declared the idea dead in the water, stating the recent deaths (in June 1938) of a woman spectator and her two grandchildren at Penrith Speedway as sufficient reasons for the need to protect the public from the motor racing nuisance. The motor racing lobby retreated to lick its wounds, and following the Second World War, had a multitude of abandoned airstrips to play on. These presented little more than a blast up and down a flat surface, although one such airstrip, at Mount Druitt, had plans to add a sealed loop to form a circuit.

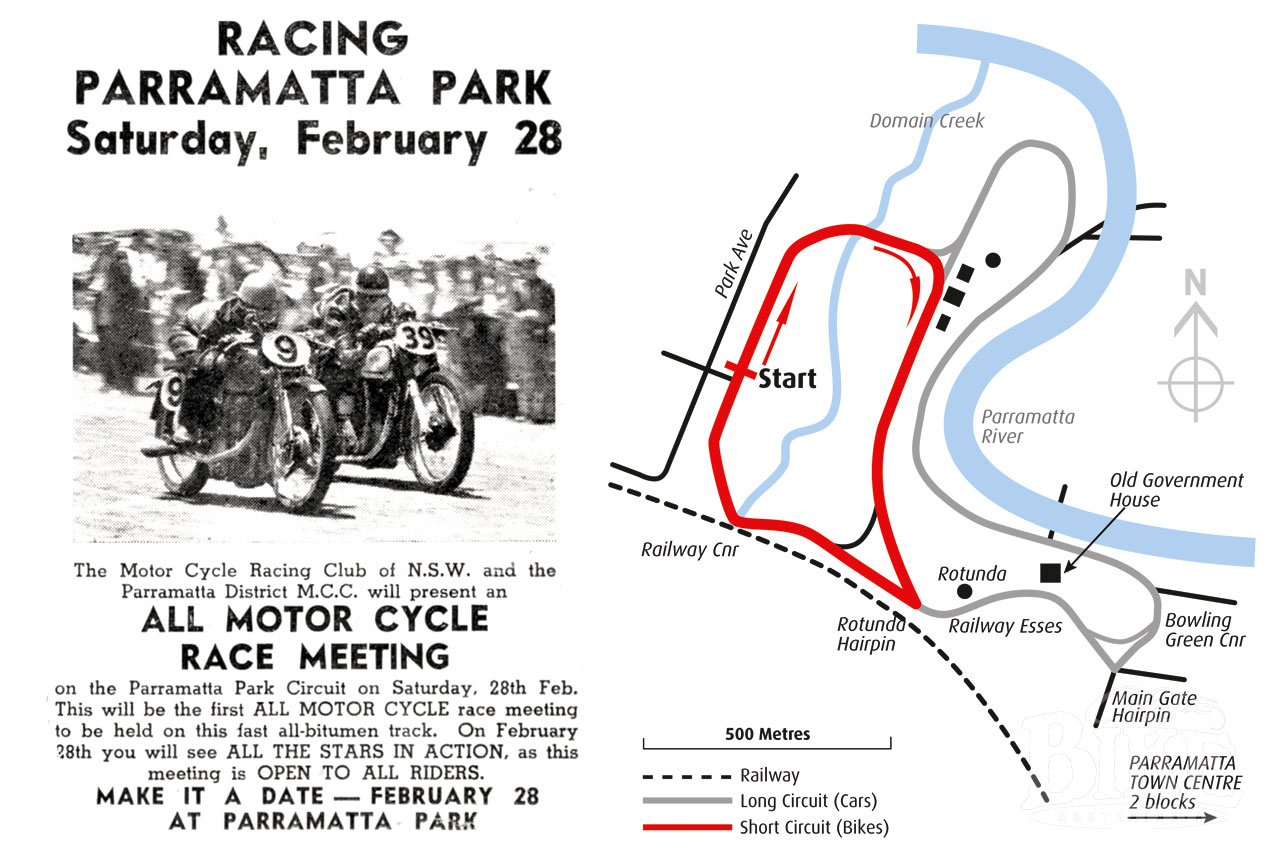

But the tantalising prospect of thrashing around Parramatta Park would not go away, and the idea was resurrected again in 1947. It was a particularly bad time to confront the NSW Police Commissioner, Mr MacKay, who had just successfully managed to have the Bathurst Easter car and motorcycle races cancelled on the grounds of public safety. Buoyed by his victory, Mr MacKay declared that his department would henceforth oppose all applications for motor sport in the state. It took a change of Commissioner and a great deal of groundwork to get the Parramatta proposal off the ground the second time around, and it was not until late 1951 that the date for the first meeting – 28th January 1952 – was announced. With only the annual Bathurst meeting to look forward to, it was with huge enthusiasm that the news of the procurement of Parramatta Park as a motor sport arena was greeted by the two, three and four-wheeled sporting community.

The Parramatta Park Trust and the Australian Sporting Car Club announced that they had agreed upon a plan that would ultimately see Parramatta Park developed into a full-scale Grand Prix standard circuit. To make the dream a reality, a considerable amount of bureaucratic manoeuvring was necessary, and local businesses pledged the not inconsiderable sum of £10,000 towards the set-up costs.

The opening (cars-only) meeting was run on a two-mile course that contained a ‘no-passing’ zone on the very narrow stretch beside the river. 20,000 race-starved spectators flocked to the park to see the heroes of the day, Stan Jones, Doug Whiteford and Alec Mildren do battle. The big crowd and the enthusiasm of the local community (if not the Police) led to the announcement that a further four meetings would take place in 1952, all on Saturday afternoons. with at least four races per year for the following five years. Among the spectators at that first meeting were many members of the motorcycling fraternity, and almost immediately negotiations between the Sporting Car Club, the Motorcycle Racing Club of NSW, and Parramatta MCC got under way. An agreement to run a combined car and motorcycle meeting was eventually reached for Saturday September 6th.

Running race meetings on Saturday afternoons was a plan that Parramatta Park mainly stuck to for the duration of its short existence. Practice was held in the morning with racing starting at 1pm. This supposedly gave spectators time to work in the morning and enjoy racing in the afternoon, and, in the summer months, early evenings. The ploy never really worked, putting the motor races in competition with football and cricket, and after the euphoria of the first meeting, it was a constant battle to attract the paying public to the venue.

A tragic start

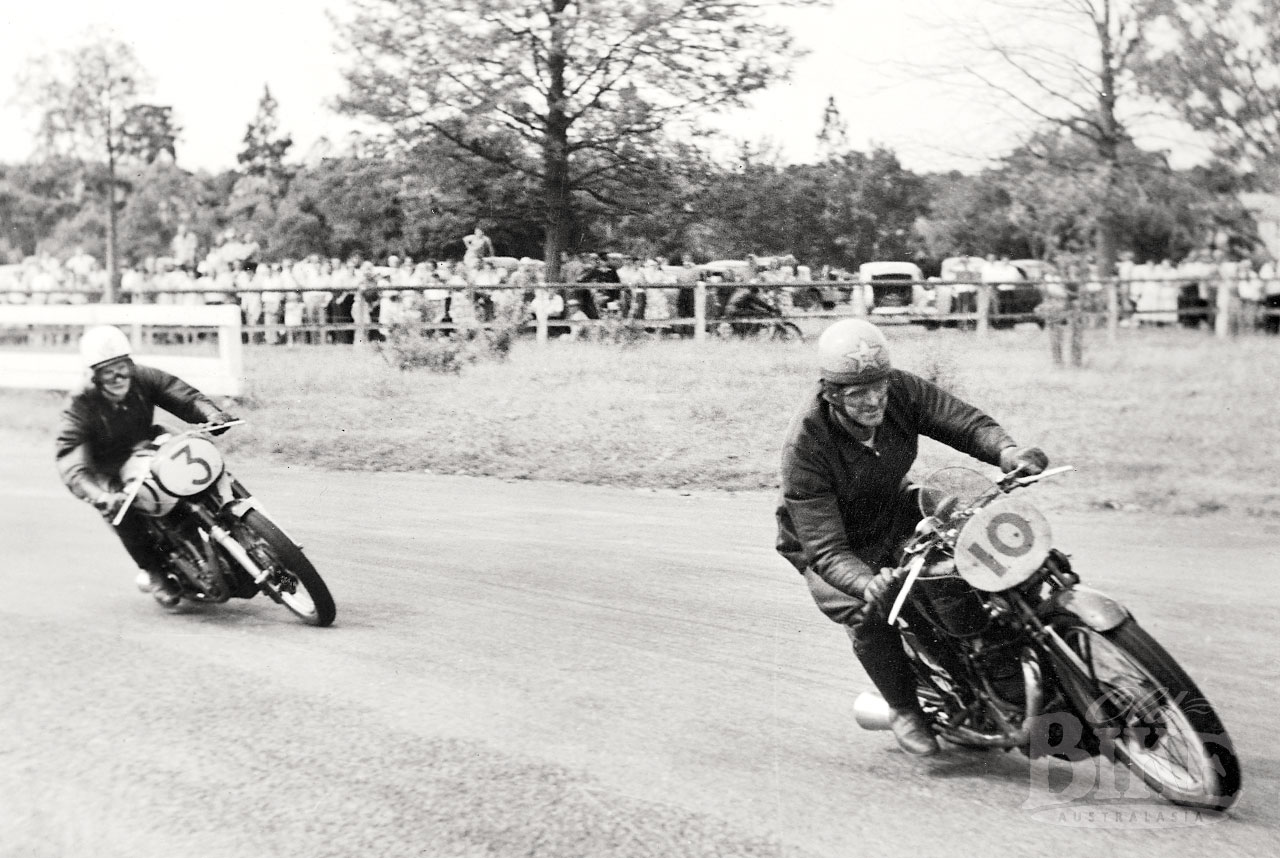

With no tar circuit racing in the state since Easter 1952, competitors and spectators alike keenly eyed the approaching September date. For this meeting a shortened, roughly triangular-shaped 1.1 mile circuit was used. This layout was retained for all the motorcycle races, as the section beside the river (the ‘no-passing’ zone for cars) was lined with trees virtually to the edge of the bitumen and was entirely unsuitable for bikes. The lap was nearly all right hand corners, with a sweeping left up hill to a hairpin around the Rotunda, then back down the hill again against the backdrop of the railway viaduct. For the September meeting, the four bike races were squeezed in between eleven car events, with motorcycle entries limited to riders from six nominated clubs – Central, Western Suburbs, Bankstown-Wiley Park, MCRC, Parramatta and Annandale-Leichhardt. Although this kept the overall competitor numbers down, the entry list nevertheless contained many top names.

On only the second lap of practice, disaster struck when the organising secretary of the meeting, 32-year-old Bernie Yates, struck a tree on his Norton and was killed instantly. It was a tragedy in more ways than one. Yates left no assets, a pregnant wife and five children under ten years of age. In typical fashion in these most dangerous times, an appeal was set up to raise money for the devastated family.

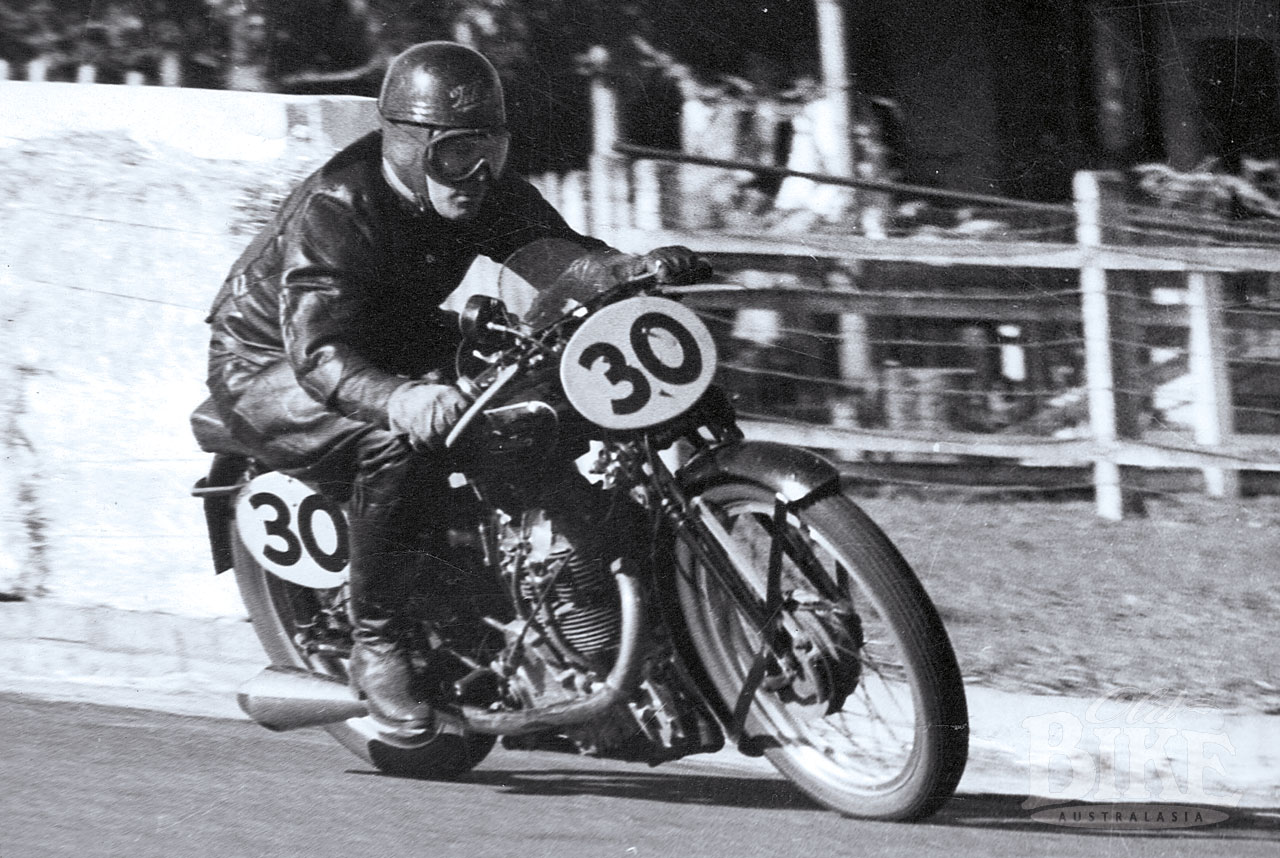

But the show went on, starting with the 125 and 250 races which were run concurrently. Bob Brown, on Allen Burt’s MOV Volocette, and Sid Willis made the running, with Harry Hinton Senior, on his home-built DOHC 250 cc Norton charging through after a bad start, only to have his carburettor fall off on the last lap, leaving Brown to take the 250 win. Keith Davis (Puch) was an all-the-way 125 winner. A number of car accidents meant that the Junior race was half an hour late in starting, and when the flag finally dropped Monty South and Bob Brown set about disputing the lead, until both were dispatched by the flying Alan Boyle who cleared out to win. The day’s final motorcycle event was the Senior, where Hinton elected to ride his 350 due to the tight and bumpy nature of the circuit. Once again Boyle and his KTT Velocette forged to the lead and ran away with the race, while Hinton and Art Senior struggled after bad starts. Jim Madsen, revelling in the handling of his brand new ‘featherbed’ Norton, held off the fast finishing Hinton to take second place.

The bikes were scheduled to again share the programme with the four-wheeled devices at another Saturday meeting on November 15, 1952. Unlike the earlier restricted event, this was an open meeting, promoted by MCRC, and unlike the previous meeting that was plagued with delays and finished in the twilight, every race started on time. Most of the NSW stars were entered, but they more than met their match in young Maurie Quincey from Victoria. The newly-married Quinceys were, in fact, on their honeymoon in Sydney, but Maurie had thoughtfully packed his ex-Ken Kavangh 350 Norton into the ute in the hope of covering some costs. As the editor of Victorian Motor Cycle News dryly remarked in his report, ‘young Maurie must be the first bloke to take a feather bed on his honeymoon!”

Allocated four events in the programme, the bikes began with the 125 race, easily won by Wollongong’s Bill Morris on his six-speed BSA Bantam from Ron Mansfield and Keith Davis. It was a much closer contest in the Lightweight, with Bob Jemison, Sid Willis, Alan Boyle and Harry Hinton staging a ding-dong battle for the whole race, the verdict going to Willis in a blanket finish. The disappointingly small crowd was on the fences to see the 350 race, where Quincey received a rear-of-field starting position in the ballot. Nonetheless he tore through the pack, while Boyle displaced early leader Bill Harrison. By lap three Quincey was right on the KTT’s back wheel, and slipped ahead under braking for the hairpin. For the remainder of the eight-lap race both men rode on the limit, with Quincey taking the win by half a machine’s length. Quincey established a new lap record of 60.2 seconds. The 500 race was something of an anti-climax after Boyle blew the start and Quincey rode off into the distance, breaking the lap record on every tour – including the push start. Jack Ehret filled third on a pushrod Matchless.

The slide to oblivion

For the first all-motorcycle meeting on February 28, 1953, where sidecars appeared for the first time, along with two Clubmen’s classes, Boyle was expected to star again. He was in scintillating form, having annexed the Australian Junior TT a few weeks previously at the Little River road circuit west of Melbourne, soundly beating hot favourite Quincey in the process. Three weeks before the Parramatta Park date came the opening of the Gnoo Blas circuit at Orange, which once again promised a Quincey/Boyle clash in the Junior, with the added spice of Tony McAlpine and Harry Hinton on Nortons. Sure enough, a battle royal commenced, but on the tricky lower section of the circuit, Boyle crashed and died from his injuries. With the all-important Easter Bathurst meeting only a few weeks away, top-line riders largely avoided the Parramatta meeting, resulting in a very poor crowd and a large financial loss for the promoters. The NSW Motorclist newspaper branded the meeting ‘the greatest flop yet witnessed in this state’. Clubman rider Ross Pentecost was outstanding on the day, winning the Senior Clubmen’s and leading the Aces Scratch Race until he broke a chain, the win going to Reg Corbett. Bill Harrison (AJS 7R) was the Junior winner, with Jack Ahearn (Norton) taking the Senior, Keith Farrell the Ultra Lightweight. It was generally held that the Saturday afternoon races had no future, but there also appeared little chance of gaining the use of the venue on Sundays. The whole situation at Parramatta Park was becoming ever more tense and difficult, with constant rows between organisers, police and local government.

A low-key meeting featuring teams racing between Western Suburbs, M.C.R.C., Parramatta, Central, and Bankstown-Wiley park took place on Saturday September 26th September, 1953, with proceeds going to the Sun (newspaper) Toy Fund. Ten events were contested, with M.C.R.C. coming out on top, thanks largely to the skills of their veteran captain Harry Hinton Senior. Other notable performances came from Parramatta’s Johnny Shanks, brothers Keith and Len Roberts, Keith Stewart and Bob Brown.

The opening of the new 2.2 mile Mount Druitt circuit the previous year had posed yet another problem for the Parramatta promoters. Crowds and competitors flocked to the new track, and continued to largely avoid Parramatta, with its cramped conditions and other difficulties. Cars persevered with the venue, but after the crippling loss on the 1953 meeting, the bikes seemed quite content with a race meeting almost every month at Mount Druitt. However it was the deterioration of the track surface at Mount Druitt that gave Parramatta one last tilt. Following the 24 Hour car races and the similar motorcycle marathon in 1954, several bike meetings were cancelled with the track deemed unsafe. The ACU had an agreement to hold two meetings in aid of the Sun (newspaper) Toy Fund, and the first of these was switched to Parramatta.

Parramatta Park played to its biggest crowd not for a race meeting, but as the start and finish points for the Redex Trial in June 1954, when thousands of onlookers lined the fences to see off the 108 starters, then, one week and 2,500 freezing miles later, to welcome the 71 finishers back home.

This final motorcycle meeting, on October 3rd 1955, was also the last race meeting of any kind at the venue, and ironically drew the best entry and the largest race crowd yet. Star of the day was Parramatta clubman Len Roberts, with his newly-acquired Manx Norton. Alas, young Len had only two weeks to live, as he died after hitting a horse while practicing for the Mount Druitt 24 Hour Race. To raise funds for his family, the Norton was raffled with 600 tickets being sold for £1 each.

An attempt to re-start competition at the venue was made in 1958, as part of Parramatta’s 150th birthday celebrations. But the resolve of the Police Commissioner had hardened even further, and permission to close the public roads within the park was refused. In fact, only months later, came the draconian NSW Speedways Act, which spelt the end for every such track in NSW, including Orange and Mount Druitt. Racing in NSW had reached its lowest ebb, with only a handful of dirt tracks, plus Mount Panorama receiving a licence to operate. The situation would not improve until a spate of new circuits, including Oran Park and Catalina Park at Katoomba, opened in the early ‘sixties. These tracks had been designed with the licensing requirements in mind, rather than trying to adapt existing facilities.

The roads within Parramatta Park that once resounded to open megaphones are still there, although a one-way system prevents any attempts at the old lap record, and the uphill run to the Rotunda is now for pedestrian traffic only. Today, Parramatta’s towering business centre and the adjacent football stadium cast shadows over the lawns where spectators once enjoyed their corned beef sandwiches. Still, it’s not hard to imagine the sight and sound of the Hintons, Ahearn, Boyle, Quincey and Willis as they thundered around more than fifty years ago. And it’s quite certain that, in this country, the luxury of a permanent road racing circuit bang in the middle of a city will never happen again.