Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Technical assistance: Paul Reed

As the 1970s dawned, it seemed just about every major manufacturer was either working on or thinking about producing a motorcycle powered by a variation of the NSU/Wankel rotary engine. Honda built and tested a prototype, named the CRX, Kawasaki came up with the X-99 and built several ‘mules’, while Yamaha went even further and publicly released the twin-rotor RZ-201 at the 1972 Tokyo Motor Show. Meanwhile, in Germany, the giant Sachs/Hercules concern was seriously gearing up for production of the W-2000. Ironically, while the 1970s fuel crisis was one factor in the demise of the rotary concept, the fuel crisis of the 21st century could be a catalyst in its revival. Serious development is known to be taking place on hydrogen-powered Wankel-style rotaries, producing excellent results with virtually negligible exhaust emissions.

Suzuki RE-5 – A vane attempt

By August 1972, Suzuki was well advanced on two separate versions of its rotary project and had purchased a full manufacturing licence from NSU/Wankel as far back as 1970. Their engineers came up with both single and dual rotor versions, with the single due for first release. But at the last minute, the debut of the RX-5 (later renamed RE-5) at the October 1972 Tokyo Show was cancelled – Suzuki management deciding to keep their powder dry for a few more months, and convinced that no other Japanese manufacturer was anywhere near as advanced on rotary design.

The Yamaha stunt absolutely pole-axed Suzuki, particularly when it was announced that the RZ-201 would be in dealers’ showrooms by February 1973. Clearly, the single-rotor Suzuki was going to look rather weedy beside the big Yamaha. But within months it became clear that the Yamaha rotary had been stillborn, and Suzuki redoubled its efforts. But Suzuki had problems of their own with the twin – sealing, overheating, carburation, plus issues like noise from the timing chain and the need to substantially revamp the transmission to cope with the enormous torque – and with the bills from the rotary project already well past Aust$100 million, decided to concentrate on the single-rotor model to launch the concept.

At the show, Suzuki displayed three different colour variants of the RX-5 – designed by Italian car stylist Giorgotto Guigiaro – while the Yamaha RZ-201 was now seemingly a distant memory. Exactly one year later – at the 1974 Tokyo Show – the final production single rotor model, now officially named the RE-5M was displayed, ready for dealer orders. Suzuki had not given up on their twin-rotor model, and in fact items such as the huge radiator were designed to cope with the bigger engine.

It was January 1975 before the RE-5 was delivered to the first customers, many of whom had waited four months since placing orders. This delay fuelled rumours that the model was experiencing the same sorts of reliability problems that had killed off attempts from Suzuki’s rivals. When the RE-5 was finally made available for magazine road tests, the reports were encouraging. It handled very well, had an excellent spread of power, and good brakes.

The initial sales burst however was short lived. Within six months dealer orders had dropped off markedly, not helped by a factory recall to cure carburettor problems and several other niggling faults such as spark plug fouling. There were also problems with first and second gear, again a legacy of the engine’s torque. An unforseen dilemma was the fairly high fuel consumption, which became a major issue as the energy crisis took hold. At around 30 mpg average, fuel economy was not a strong point, while the exhaust emissions were in the ultra-high bracket.

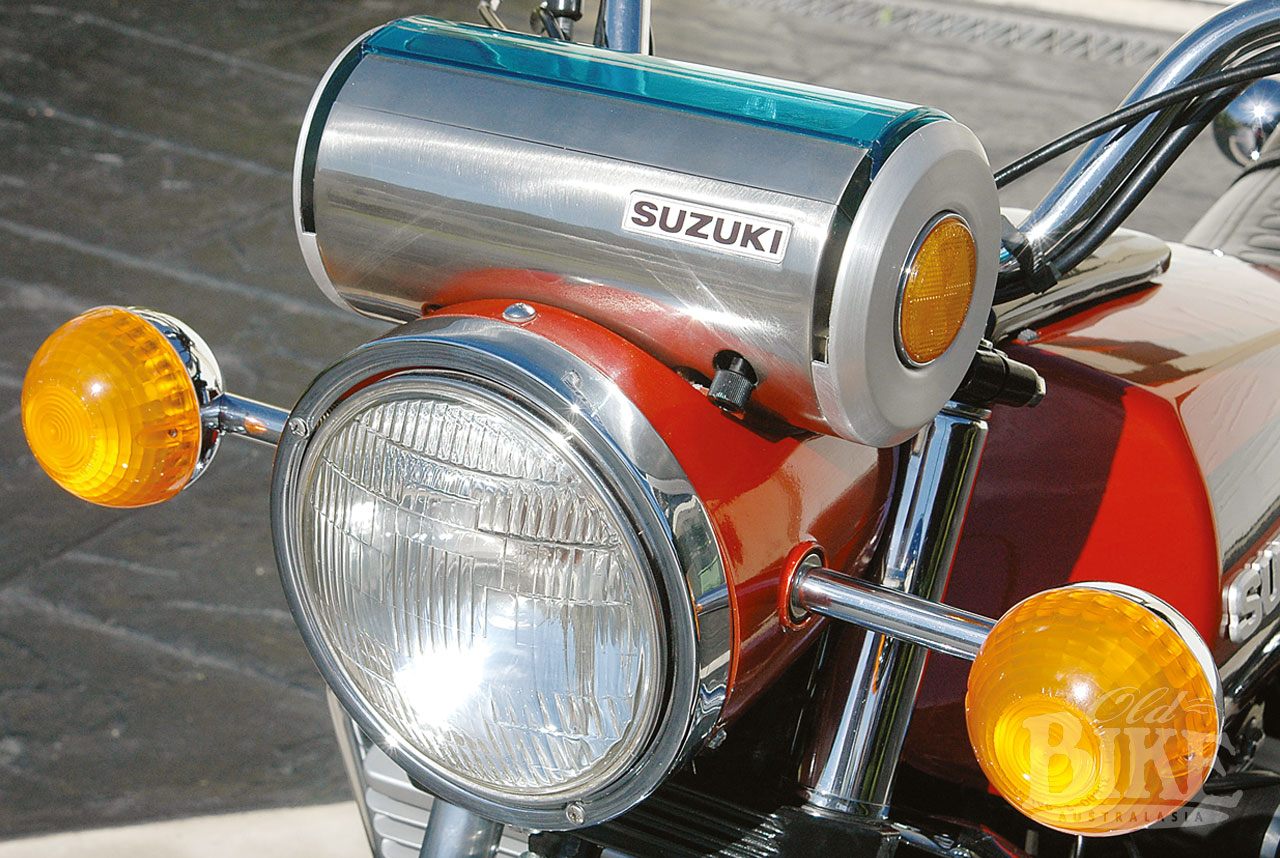

In reality, one of the biggest factors influencing customers was the styling – a product of an Italian design company that specialised in cars. Quirky items such as the ‘bread roll’ instrument cluster, (with the styling carried over to the tail light), baseball size indicators and the dual-skinned, vented exhaust system did not help.

Abandon ship

As sales plummeted, Suzuki decided to give the RE-5 a major face lift to create the 1976 ‘A’ model by transferring much of the more conventionally styled running gear from the GT750. Instead of the avant-garde orange and blue décor of the M models, the A came in traditional black. To defuse perceptions about reliability, Suzuki offered a lifetime warranty on the rotor unit, with 12 months warranty of the bike itself. But still the RE-5 sat forlornly on showroom floors, and in late 1976 the decision was quietly taken to kill it off, even though the R&D department, housed in the purpose-built rotary-only factory, were almost ready to go with the twin-rotor 1000cc ‘B’ model. Of the 7,000 RE-5s produced (4,000 M-series and 3,000 A models), nearly 60% were sold in the USA.

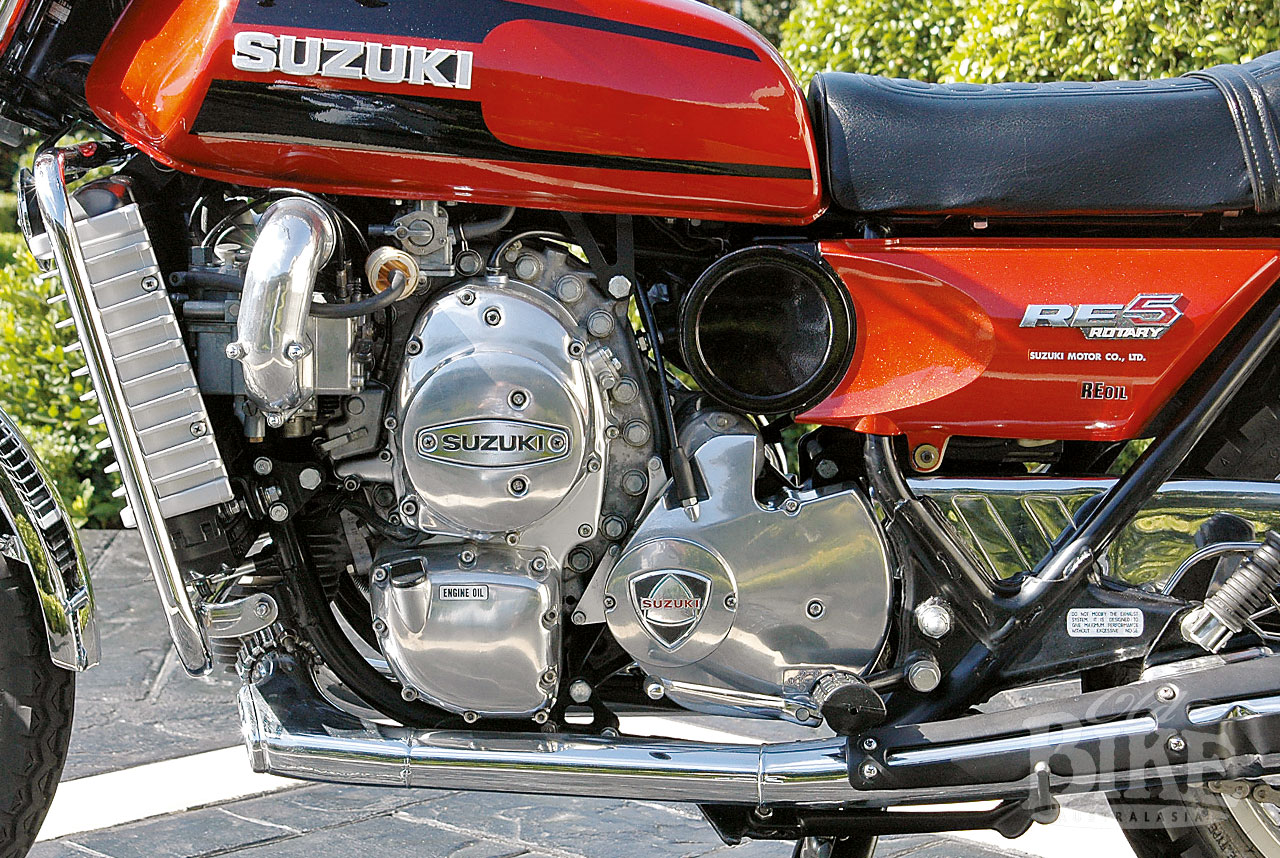

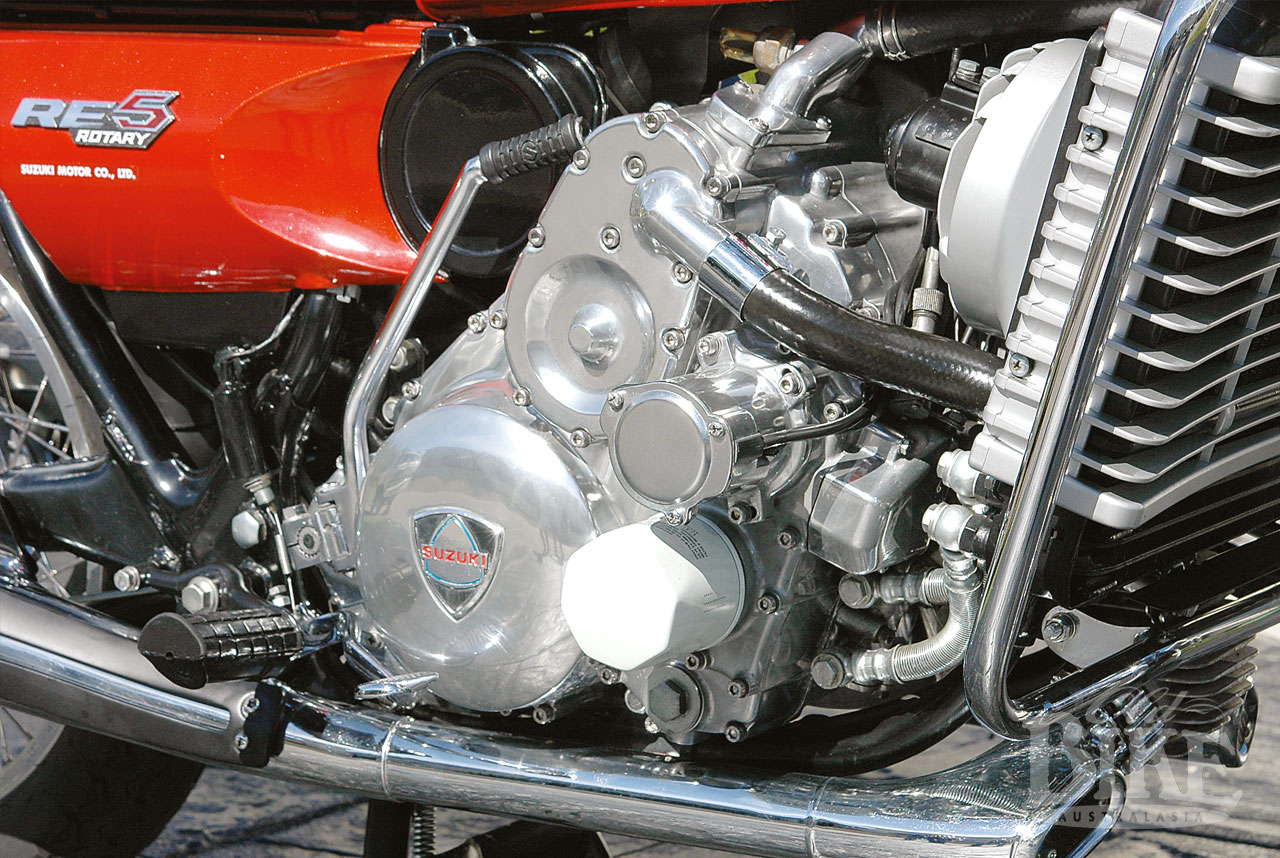

Heat, or the dissipation of it, was one of the major problems with the RE-5, which had two distinct cooling systems, with three separate oil sumps, two oil pumps and two radiators. Oil is pumped from the first sump to cool the rotor and internal components, and is cooled via its own small radiator, located below the main one. The outer jackets carry water through a complicated passageway of ducts which were designed to maximise heat exchange. The water radiator incorporates a thermostatic fan which is vital to control heat build-up.

Stainless steel exhaust pipes are encased in chrome-plated shrouds with an air intake through a grill at the front. This allowed air to flow between the pipes and the shields and this air mixed with the exhaust gases before exiting the system. Despite the double pipes and the additional black heat guards, the exhaust system reaches enormous temperatures.

Although the Wankel engine is extremely simple in its design, the peripheral systems are enormously complex and open to the interpretation of the various engineers. The intake system on the Suzuki is one case in point, utilizing a 2-barrel, 2-stage Mikuni carburettor that varied from 18-32mm. The twist grip has five separate cables to pull. Despite the incredible attention to mixture control, the RE-5 is generally unhappy running at low rpm, although silky smooth when revs built up.

The ignition system is another curious piece of Suzuki engineering, using two sets of points for a single spark plug. One set fires every rotor ‘face’, while the other is activated by a sensor in the rev-counter, a relay and a vacuum-operated switch to cut out the first set of points to assist in engine braking. The second then set fires every other rotor face to reduce contamination in the combustion chamber by un-burned fuel/air mixture.

One man’s RE-5

Wayne Waddington is a First Officer with Qantas and a self-confessed Suzuki aficionado. His collection includes a GT750M which is in the mid-stages of a restoration and an almost-finished GS750B – Suzuki’s entry in the 4-cylinder four-stroke ‘superbike’ stakes. Wayne is also completely fastidious in his work, resulting in the stunning restoration of the Firemist Orange model you see here.

But coming into possession of the RE-5 was not the result of a crusade to unearth such a rarity, just a chance scan of the ads in the Sydney weekly paper The Trading Post back in 1980. The RE-5, with just 8,000 km on the clock, was advertised for $800. It had spent five years in a shed, refused every effort to start it, and was advertised in ‘as is’ condition.

“I wasn’t looking for a rotary, I bought it because it was cheap,” Wayne says 26 years later. “At the time I was into long distance riding and my wife and I rode the RE-5 all over the place, including outback dirt roads. Then in the early 1980s I stopped riding and put the bike away for nearly 20 years. When I dragged it out in 1999 the brakes had seized, the lacquer covering the polished surfaces had cracked and gone yellow and there were internal and external oil leaks. It’s incredible what just sitting in a shed does to a bike.” It was time for a full restoration.

“I wrote to the (Suzuki) factory but they had totally disowned the model – it was as though it never existed. Then I discovered Sam Costanzo’s web-site (Rotary Recycle) and this changed everything. I could see that rotaries in general and the Suzuki in particular had a huge following world wide. I managed to get a new (M series) fuel tank in Australia. The kits Suzuki supplied to convert the RE-5M into the RE-5A, contained a fuel tank, headlight shell, instrument cluster, indicator lights and tail light, but the factory’s instructions were that all the M-series parts had to be destroyed. Most were, but a few survived.”

“The biggest bugbear of this bike is the spark plug,” Wayne says, pointing to the almost-concealed item poking from the rear of the engine. “It can last as little as 50 kilometres, but certainly no longer than 2000 kilometres, and even in 1977 they cost $10 each. Now, if you can find one, they cost around US$50.” The standard plug is a NGK AU10EFP – a 18mm item with a conical seat. A partial solution is to use a 14mm B8ES with a 18mm adapter sleeve, or if you’re lucky you may come across the Czech BERU equivalent.

“Because of the timing of the primary and secondary ports, the engine, when incorrectly tuned, can develop a hesitation, or flat spot, at low revs, and that can make it a bit of a chore riding it around suburban streets. However I have managed to eliminate this, and written reams of information on the web group sites to help others tune out the hesitation. It is a very heavy bike and it gets very hot in traffic, affecting the comfort of the rider – unpleasantly so, especially if the fan turns itself on.”

“Wankel engines have a reluctance to decelerate on overrun. This is partially due to the inertia of the comparatively heavy rotor and perhaps to other reasons as well. This can lead to a complete lack of engine braking and the surging as the rpm falls. In racing circles with Mazdas, one way that they cured the problem was to cut off all ignition whenever on overrun. This gave decent engine braking but the downside is that unburned gasses and other contaminents built up in the rotor and could then lead to sealing problems at the tip seals. Having ignition on all the time, accelerating and decelerating, (the RE5’s “A” points) kept the rotor very clean but left the aforementioned problems on overrun. Suzuki’s solution was to install the second set of points which was a compromise between the clean full ignition on overrun and the racing solution of no ignition at all. The “B” points fire the rotor face every second time. This gives some engine braking, reduces the surging at low rpm on overrun and keeps the cylinder cleaner than in the racing engines. As mentioned, Suzuki abandoned it on the A models, disabled it on the M’s. Sam Costanzo tells me he sells a lot of gear to restorers keen to reactivate the old disabled B systems. With the points enabled, the bike is far better – the low rpm surging is vastly improved and the bike has markedly improved engine braking. When disabled, the rotor is kept slightly cleaner, so maybe Suzuki was worried about long-term warranty issues.”

“Warming up the engine is absolutely critical, and can take several minutes. If you don’t adhere to this, plug fouling is the probable result.” Despite these quirks, Wayne defends the RE-5 staunchly. “It is a brilliant handling bike – everyone who rides one is amazed at just how well it behaves, and the early road tests substantiate this.”

The RE-5’s signature oddity is that instrument cluster, and the unit on Wayne’s bike has just returned from a lengthy refurbishment by Sam Costanzo in USA. No matter how careful the reassembly, it seems inevitable that moisture will penetrate the rubber seal, and the strange-looking semi-circular Perspex cover, which swivels up when riding (and was available in a variety of colours) does little to assuage the problem. Sam however, guarantees his job to be completely waterproof and he does about 20 per year.

Another nightmare facing the home restorer is the wiring harness, which has been described as ‘frightening to behold’. The loom caters for touches like digital gear indication, fuel warning light, secondary oil tank warning light and the usual ancillary lamps, and presented a severe challenge to the workshop handyman and trained mechanic alike thirty years ago.

A solution to the carburettor maladies is now at hand through a specially modified SU unit which will hopefully be marketed internationally in the near future.

Foibles, quirks and oddities aside, the RE-5 draws an immediate crowd whenever it appears at rallies and displays, for it represents that envelope in history when rotary power was seriously seen as the next big thing in motorcycle design. And unlike manufactures like DKW, Norton (and the Dutch Van Veen) who adapted engines from snowmobiles or industrial designs, the Suzuki was built from the ground up as a motorcycle power unit, with the factory throwing almost unbelievable resources at the project, the development of which lasted far longer than the actual production model.

*The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Sam Costanzo’s Rotary Recycle in compiling this article.

1975 Suzuki RE-5 Specifications

Engine type: NSU/Wankel rotary, liquid cooled

Displacement: 497cc

Power: 62 hp @6,500 rpm

Torque: 54.9ft lb @ 3,500 rpm

Carburettor: Mikuni 18-32 HHD

Comp ratio: 9.4:1

Start: Electric or kick

Transmission: 5-speed

Ground clearance: 17.5cm

Front tyre: 3.25H19

Rear tyre: 4.00H18

Tank capacity: 17 litres

Wheelbase: 150cm

Dry weight: 230 kg

The German Slant

The giant Hercules/DKW concern chose to plunge into the same pool as Suzuki – displaying no fewer than five examples of the air-cooled Fitchtel & Sachs snowmobile-engined W-2000 model at the 1973 Tokyo Show. All used two-stroke style pre-mix fuel and were products of a design that dated back to 1971. One had a Sachs tank badge and another a Hercules badge, using the single KC27 engine, another Hercules with a KM24 single and a shaft drive with BMW transmission. They also displayed variants with DKW and Victoria badges – all names owned by the conglomerate. An in-line, fully-working KM914 “Big Twin” rotary engine was also shown.

With over 40,000 examples of the basic power unit sold around the world in snowmobiles, boats, pumps and stationary industrial power plants, Sachs expected a smooth transition to motorcycle use, but when subjected to the needs of running in traffic and delicate throttle response, it was lacking in several respects.

The Wankel generally behaves more like a two-stroke than a four-stroke. It shares with the former the lack of positive scavenging, which results in uneven running on light loads, and the lack of engine braking. Suzuki found these traits unacceptable, and set out to eliminate them by using a complex dual ignition system, whereby when under load, the plus fires at each rotor face. When the throttle is partly closed, the increased vacuum is detected, and the ignition system fires the plug only on alternate rotor faces. Hercules-DKW used exactly the opposite approach. As a prototype, Hercules simply fitted its existing Sachs KC27 petroil-lubricated motor into a shaft drive 250 BMW frame, and it worked. For the production version, it reverted to chain drive, with a transversely-mounted longitudinal gearbox. As the rotor shaft was located longitudinally, this necessitated a pair of bevels between the motor and the gearbox.

Hercules went too far in its attempts to produce a simple machine. Rather than face the complication of a separate oiling system, it stuck to petrol-oil mixture. This was not only unacceptable on the grounds of inconvenience, it resulted in much-reduced performance. To cool and lubricate the rotor and its bearings, the incoming charge first passed through the centre of the rotor, before being looped back through a very restrictive porting system into the peripheral inlet port. At the front of the engine, carried on the centre hub of the fan, sat the magnets for the 100W alternator and magneto, with ignition and lighting coils on a stator plate within the hub.

Predating the Suzuki by a few weeks, the W2000, badged as a Hercules, made its public debut at the Los Angles Hilton in September 1974. It took another three months before deliveries were made to dealers in the USA. Buyer resistance centred around the antiquated petrol-oil mix, and one year later an new model, fitted with oil-injection, was introduced. Sales took a sharp upturn but then, in November 1976, the factory abruptly stopped production, ostensibly because the model had fallen marginally short of the minimum accepted production quota. A string of newly-enlisted dealers were left frustrated, with plenty of customers but no bikes.

In Australia, the W2000 came as a DKW, with tank styling and colour scheme seemingly stolen from, rather than based upon, a 1971-model Honda CB250. Chassis-wise, the DKW was impressive, with a tubular backbone frame supporting the underslung engine in Aermacchi style. Up front were Ceriani forks and a single 300mm Grimeca front disc with double-piston caliper. Spanish-made Bosch headlight and starter motor. The DKW came with a six months or 10,000 km warranty, but advertising brochures proudly stated that the engine should do 100,000 km before requiring any major rebuilds.

I had the opportunity to ride a W2000 during a recent visit to Paul Reed in Queensland. It’s a totally unique experience, rather like half way between a two-stroke and four stroke, with a performance level approaching the Japanese 350s of the period. There’s plenty of middle range torque, but no point in revving the engine hard, as the power stops dead at 6,000 rpm. You certainly notice the lack of engine braking into corners, but overall, the DKW handles and brakes exceptionally well. Ground clearance on the left hand side needs watching, as the centre-stand snags the deck quite easily, but generally the DKW can be flicked around effortlessly – it’s comfortable and the controls, seat height and pedals seem ideally positioned to me. If you’re looking for a classic that really is different, it’s worth thinking about a DKW…or a Hercules…or a Sachs.

1974 DKW W2000 Specifications

Engine type: NSU/Wankel rotary, liquid cooled

Displacement: 294cc

Power: 32 hp (23.9 kW)@6,000 rpm

Torque: 25ft lb (34.3 Nm)@ 4,500 rpm

Carburettor: Bing 32mm CV

Comp ratio: 8.5:1

Ignition: AC magneto

Start: Electric or kick

Transmission: 6-speed

Ground clearance: 16.5cm

Front tyre: 3.00 x 18

Rear tyre: 3.25 x 18

Tank capacity: 18 litres

Wheelbase: 143cm (56.3 inches)

Dry weight: 173 kg

Price (June 1975): $1989

British bent

As if to cement the rotary revolution, yet more variations on the theme – from Norton Villiers Triumph – appeared at the 1973 Tokyo Show. One used a Sachs KM24 snowmobile engine doubled up to form a twin, while the other had a similar treatment to a Sachs KM914 industrial engine. Initially, these used the Sachs petrol-oil mixture system, which was soon discarded. By taking the incoming charge directly into the the peripheral inlet port, the power output was almost doubled. By substantially increasing the power output of each rotor, and doubling the number of rotors, there was plenty of poke. By mounting the rotors transversely, the need for bevel gears to the transmission, on the Sachs design was eliminated.

The British attempts at a rotary engine motorcycle had begun with BSA back in the late 1960s, with a Sachs unit installed in a A65 chassis. A few years later, a Wankel twin-rotor unit was crammed into the chassis of the stillborn 350cc Triumph Bandit, while later variants, known as the P39, used the Triumph twin “oil in the frame” chassis. It took until 1979 to refine the concept into an air-cooled machine with Norton on the tank. It used a Triumph T140 five-speed gearbox with a box-section frame holding oil but despite pre-publicity, never went into production.

The first rotary Norton to make it into production (about 500 in all) was the Interpol II, with chassis components, fairings and ancillaries developed for the British police on the Commando-engined Interpol in the 1970s. The fairing bore a marked resemblance to the BMW RT series and the engine had been converted to Boyer Bransden electronic ignition. The general public were finally able to buy a Norton rotary with the release of the P43 Classic –essentially an Interpol II without a fairing, and just 100 or so were built, making this something of a collectors’ prize these days. It became common practice to strip ex-police Interpol II models and convert them to Classic specs. A water-cooled version was shown in 1989, and made it into production as the police-only “P52 Commander”. Once again a public version was slow in evolving, and when it did, the fully-faired P53 Commander was hardly an electrifying experience. Some parts were sourced from Japan (such as the Yamaha XJ900 front forks). It was a curious piece of marketing, as at this time the John Player Special – sponsored Norton racing team was enjoying major success and the public clamouring for a road-replica of the racer. What they got was a clumsy tourer that was overpriced and under-specified.

Finally the enigmatic owner of the Norton marque, Phillipe Le Roux stepped in and demanded a racer replica be created, and the result was the P55, or “F1”, now one of the world’s most collectable motorcycles. Again, Japan supplied many of the components, such as the Yamaha FZR1000 gearbox and hydraulic clutch, but the tiny machine with its fully-enclosing, tight-fitting fairing suffered badly from the old rotary bugbear of overheating. After the P55 failed to meet emission laws in one of its biggest markets, Germany, production stalled after around 130 had been produced.

But the Norton rotary concept had one more card to play. Officially known as the P55B or F1 Sports, the final incantation appeared in 1991 and used the fairing, tank and seat from the successful racer, giving far better cooling. Emission problems were largely cured by reverting to SU carburettors, but in reality this was a marque in its death throes and when the stock of parts left over from the P55 ran out, so did the P55B ticket to ride. 65 were built.

One of our regular photographic contributors, Charles Rice, has one of the very few Norton Classic rotaries imported to Australia and has clocked up a substantial mileage with virtually no problems. From his home on the NSW north coast, 80-year-old Charles is a regular commuter on the Norton to the annual Ulysses rallies. However the usually reliable Classic blotted its copybook in 2006 when its electrics failed in Geelong, just before boarding the boat the to Tasmania.

An excellent source of information on Norton Rotaries with links to other like-minded sites is: www.nortonmotors.co.uk

Editor’s Note: Charles Rice – Under the Chequered Flag

Since this article was first published in 2007 Charles Rice has passed away in late-2016 aged 91. The pages of OBA would look quite different without his magnificent photographs, which have graced this magazine since the very first issue. But Charles was much more than a gifted photographer; a very talented racer himself, innovator and mentor.