From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 102 – first published in 2022.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook • Extra photos: John Oirbans

It’s a Commando, but not as we know it.

“Does it have a name?” I asked, staring at the most unusual Norton Commando I’d ever seen. “Yes, The Bastard”, replied John Oirbans, the owner and creator of this machine. Not exactly flattering, but I suppose, apt, seeing it literally is, as defined in the Oxford Dictionary, born out of wedlock. Perhaps the inscription on the oil tank cover – TT 750 Commando – is kinder, so we’ll use that for the purpose of this article.

John Oirbans is somewhat of a legend in Commando circles. He currently has eight, including a few ‘specials’, but many more have come and gone from his workshop over the years. None, however, quite like the TT 750.

There’s always a project or two on the go at the Oirbans homestead in the NSW Hunter Valley. Not just Nortons, but other British fare including a superb Matchless G15 twin – one of the last of the hybrid models featuring an amalgam of Matchless/AJS and Norton parts assembled in the dying gasps of Associated Motorcycles. So what inspired this unique Commando bitza?

John explains the process that led to its instigation. “It started off, I had the frame, just the frame. It’s a 72 model frame but the rear loop had been cut out and the frame wasn’t good, so I straightened it up. I’ve always had trail bikes, I love bush riding and I had a ‘72 750 motor so I thought, let’s build a Norton trail bike. I started putting things together – just bits sitting on it before I went to all the trouble of making special brackets and so on. I had a Yamaha TT600 and a TT500 and I had a spare front end, so that virtually went straight into it. I also had a Yamaha seat from a 250 and that went pretty much straight on it, and it all went together pretty quick. I had a gearbox so that went in and I went to a couple of swap meets for some odd parts and over about two years it just came together.

“I rode it a couple of times and I wasn’t happy with the back end so I made the full-floater swingarm which came from a Suzuki 125 motocrosser. I welded the mounts for the twin shocks onto it and cut all the front out of it. Four times I threw it in the bin, then got it out again, I had aluminium everywhere, but finally I had it fitted. The back wheel is from a DR250 Suzuki, the front end, including the mudguard is from a KTM 500, the rear shocks are now Öhlins – I wish I had used them in the first place instead of mucking around with other stuff. The back mudguard is Honda. The plastic fuel tank is from a Yamaha IT400 – in America they can blow these up so you can get more fuel into it and that’s been done on this one. I’ve got a Suzuki DR650 steel tank that I am going to put on it next.

“The oil tank has been stretched. I cut it apart and added a section so it would hold more oil. If you’re riding long distances they get too hot, so more oil cools the motor down and they last longer. I’ve also put an oil cooler and filter just above the gearbox.

“The motor has done a fair few k’s now, it’s on 60 thou oversize with a bigger cam in it, the head’s been flowed, with bigger valves, but it’s a pretty tired motor now. I’ve got an 850 engine just about ready to put in it. I’m using a 38mm Mikuni carb – I tried twin carbs but I was never really happy with that set up so I thought I’d just go with the single to keep it simple. I’ve had it in water and mud up to the carb, no problem.”

The TT 750 has evolved considerably since the project began, but not always as a result of experimentation or development. There was one minor setback that came about entirely by accident, as John explains with the occasional grimace. “I was out trail riding on this dirt road and I came round a corner and was going pretty quick and I hit loose gravel and speared off the road. There was a big mound of dirt and I went up over that and went straight through three strands of barbed wire and it landed on the front wheel sideways. It was a big crash and the top strand of wire went under the headlight and wiped off the speedo and tacho and other stuff. The frame was bent but I rode it home, I had cuts all over me. I put up with it for six weeks but I could feel one side of me was not right, I was dragging my foot a bit and I was losing strength, so I went the hospital and they said, “You’ve got a massive brain bleed and a broken neck. So I was straight into hospital and the doctor said to me, “What do you do for a job?” and I said, “I’m a roofer”. He said, “You’ve been on a roof with a brain bleed and a broken neck?” I said, “Well, I’ve got a lot of work on!”

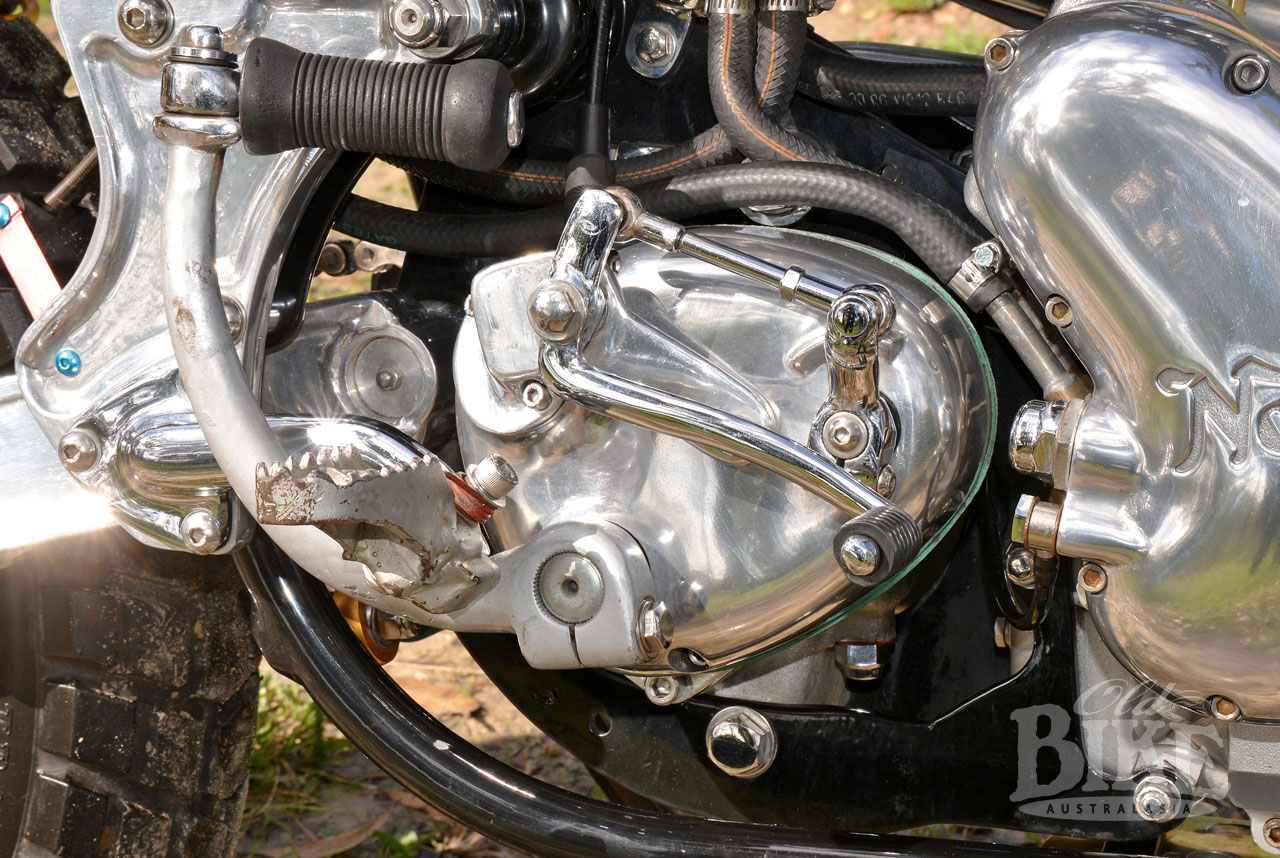

While John took medical advice and eased the pace of life a little, it gave him time to consider the best way to rebuild the wreck, which he describes as a “write-off”. “It had the XT600 front end at that stage so I had to completely dismantle it and straighten the frame again – the steering head was twisted so the front wheel wasn’t in line with the back. This time the KTM front end went in with the Öhlins rear shocks, with a Honda bash plate that actually went straight on after I welded on a couple of braces. I also made a new gear change set up to move it further back, with Husqvarna footrests. The gear change now pivots off the gearbox inspection cap with a bit welded on it. I kept the Commando alloy plates but cut off the extension for the pillion footrests and muffler mounts, you don’t need them, but I’ve always liked that aluminium piece. The speedo and tacho are Yamaha and the blinkers are just little driving lights. The front brake master cylinder is from a KTM. I had a hydraulic clutch on it but it let me down and I thought if I’m in the bush and it fails I’m in trouble, but I can carry spare cables so it came off and just a normal clutch cable went on.

“The primary transmission is a belt drive with a Suzuki clutch with a tensioner wheel. The cases themselves are Commando. There is also a tensioner for the rear chain, with a bolt-on brace between the lower rear part of the frame. That makes quite a difference to the feel of the back end. The exhaust pipes are Norton Commando, off an S model, with a heat shield off a Triumph Hurricane.

“It’s a great bike to ride,” says John with obvious sincerity. “It just handles great and everything feels just right – the riding position, the suspension, brakes, everything.” And it sounds as well as it looks.

It makes you wonder whether Norton missed an opportunity back when they really needed a breakthrough to survive. The US dirt bike scene was just beginning to explode in the early ‘seventies, and the TT 750 has what most bikes of that era didn’t; grunt without the hair-raising characteristics of the big two strokes, the sophistication and inherent simplicity of a traditional parallel twin, and the ability to combine bush bashing with serious on-road work. Plus, one of the most revered names in motorcycling, and all the heritage that went with it, including a strong dealer network in its key export market.

The TT 750 is an amazing creation; albeit not one that the purists would embrace. On the day I photographed the bike, the actual occasion was a combined gathering of the NSW BSA and Norton Owners Clubs at the incredibility popular Jerry’s Café on the Central Coast one hour north of Sydney. This meant there was an excellent display of quality British products to keep the crowds amused, but once John returned from a brief (but suitably noisy) spin up and down the road for some action shots, the TT 750 was swamped with onlookers thereafter. One gentleman scratched his chin while deep in thought and muttered, “A TT 750. I’ve never seen one before.” “And you won’t either”, replied John with a wry smile.

Is this the end of the line? Far from it. There’s plenty of stock, John’s mind never sleeps, he’s a born fettler, a talented and innovative home engineer, and there’s more to appear from his workshops yet. You just know it.