Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Brendon Thorne

Many regard the ‘thirties as the most fruitful era in terms of motorcycle innovation. Brilliant designs flowed from almost every major British factory. But the events in Wall Street killed most of them stone dead…

Unlike the majority of its counterparts in the British motorcycle industry, Matchless, the company started by Collier family initially as a bicycle manufacturer, was based in London, not the Midlands. With its comparative isolation from the nerve centre of the industry, Matchless also chose to tread a different path to its competitors. As early as 1905, their JAP-engined v-twin used leading link front and swinging arm rear suspension, and the Colliers brothers, Charlie and Harry, were dab hands on the track, riding their own products. Indeed, it was the Colliers’ friendship with the flamboyant Marquis de Mouzilly St Mars that led to the Marquis offering a ‘Tourist Trophy’ for races to be staged in the Isle of Man (and so exempt from the strict weight rules that favoured the local machines in Europe). Fittingly, the very first TT (at least the Single Cylinder class) was won by Charlie Collier on a Matchless in 1907. The brothers were also keen to break the dependence on outside engine suppliers such as JAP, and introduced their own single, an 85.5 x 85 overhead valve job, in 1912. It was not a complete break, as Swiss MAG vee-twins continued to power the larger machines, but it was a start.

The war, of course, stymied not just Matchless’ plans but those of everyone else, but when peace returned the pace of development went up a cog. New designs were everywhere, and Matchless, with an eye of the Junior TT trophy, produced a 347 cc overhead camshaft racer, with the camshaft driven from the rear of the motor. This dictated an unusual transverse valve layout, with the carburettor facing forward and the exhaust pipe emerging from the left side of the head. Although disappointing in terms of power output when compared to the Velocette yardstick, the 350 remained in production until 1928. For the 1925 model year, the company produced its own 990 cc vee twin, along with a cosmetic face-lift for most models. With the company in public hands after 1928, a plethora of new designs began to pour out, from sporty lightweights to chugging big single workhorses, but there were more exotic things in store.

The first of these ground-breaking designs appeared in 1930. At first glance the new Charlie Collier-designed 400 cc Matchless Silver Arrow looked like an in-line ohv twin, but it was actually a very narrow-angle (26º) vee twin with the crankshaft set transversely within the frame and the valve gear operated from a from a single camshaft skew-driven from the crank. Matchless modestly described the new V2 as ‘The most remarkable motorcycle ever produced”. A one-piece casting formed the two cylinder heads with a single carburettor. The oil tank was bolted to the front of the crankcase, eliminating the need for external oil lines. The chassis was just as innovative, with a cantilever-suspended rear end running in Silentbloc bushes controlled by springs and a friction damper under the rider’s seat. Launched at the 1929 Show, the new machine failed to convert the initial excitement into orders, possibly due in part to its miserly power output of just 16 bhp, which gave a top speed of 63 mph, but this did not deter the boffins at Matchless.

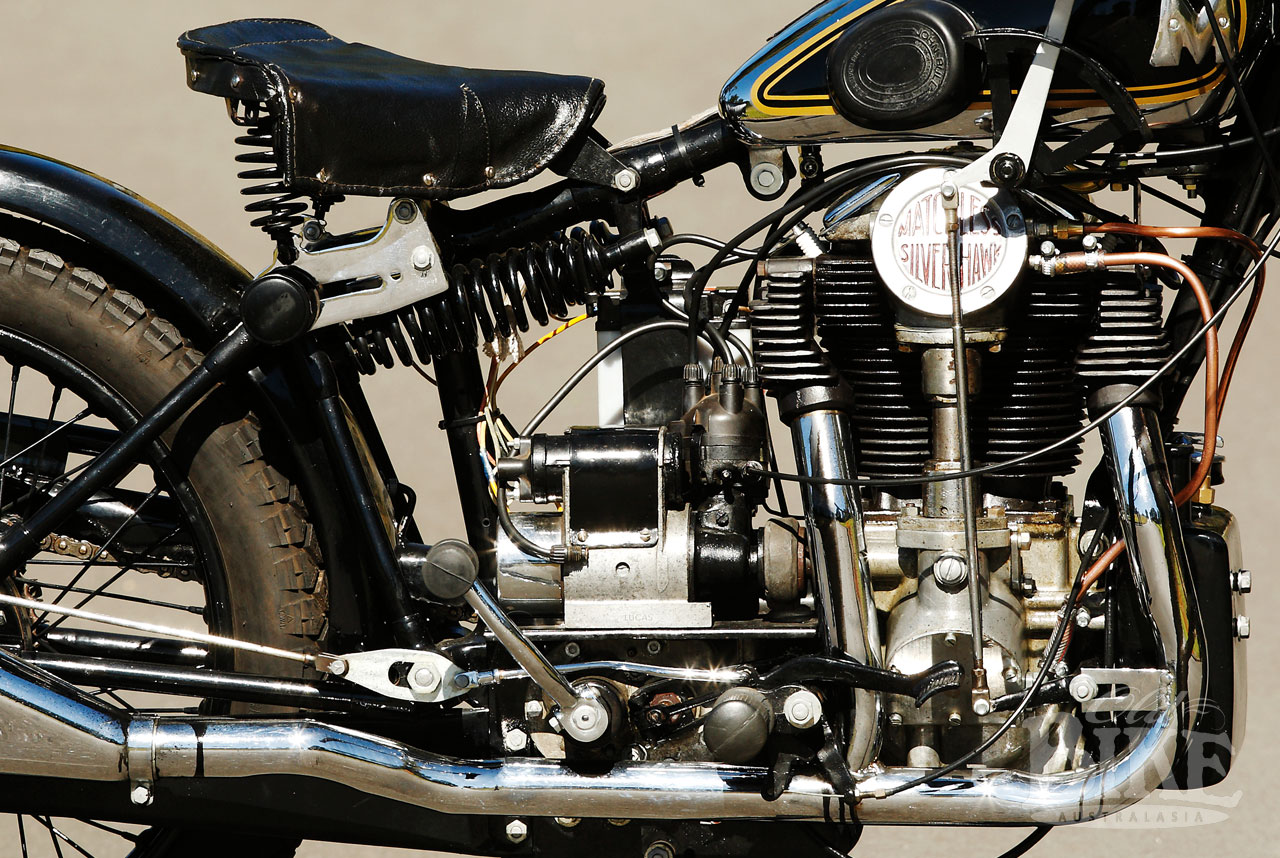

A year later they sprung an even bigger surprise – the highlight of their stand at the Earls Court Show was the sensational new Silver Hawk, another narrow angle vee design, but this time a vee-four. The Silver Hawk was trumpeted as a rival to the also-new 497 cc Ariel Square Four, but was much more radical in specification. Once again, the engine was set across the frame, with two pairs of cylinders cast together. A new four-speed Sturmey-Archer hand-change gearbox was employed, which also replaced the three-speeder on the 400 Silver Arrow. The frame and cycle parts, including the coupled front and rear brakes, were sourced from the Silver Arrow.

By now of course, the full horror of the Wall Street stock market crash was being felt around the world – hardly the time to launch entirely new and somewhat radical motorcycle designs. In designing the 597 cc Silver Hawk, Bert Collier had basically taken two Silver Arrow engines and placed them side by side, with the crankshaft running across the frame. Bore and stroke was 50.8 x 73 mm. Dry-sump lubrication was used, with the front-mounted oil tank from the 400. Like the Turner-designed Ariel Square Four, the engine was a single overhead camshaft layout, but with the camshaft driven by shaft and bevel gears via Oldham couplings instead of the Ariel’s chain. On both designs, the cylinders and heads were cast as individual units with a single left-side mounted carburettor. The Matchless used oval-shaped combustion chambers to accommodate the single spark plug and parallel valves which were actuated by straight-arm rockers. Air spaces were cast around the barrels and exhaust manifolds in a largely-unsuccessful attempt to aid cooling. Downstairs, the Matchless featured a two-throw, built-up crankshaft with a central roller bearing and two plain bushes, with roller big-ends, two-ring alloy pistons and gudgeon pins running in plain bushes. The crankshaft ran across the frame, with the conrods offset in two pairs so the front and rear cylinders were in line. Lubrication was controlled by a gear-driven reciprocating plunger oil pump, driven off the crankshaft. Oil came from the tank direct to the big ends and main bearings, then to the top bevel of the camshaft drive and into the cam box to lubricate the rockers, with a small amount diverted to the primary drive – a 3/8-inch duplex primary chain, automatically tensioned top and bottom by Weller spring-blade devices – before returning to the tank. Coil ignition was used with a car-style dynamo and distributor located behind the cylinder block.

Advertised at £75 at the Show, the Hawk was a snip compared to the 1265 cc American Indian at £125, while the other ‘four’- the Henderson – was another five pounds dearer. But despite the price advantage and the impressive technical specification, only 550 Silver Hawks found owners during the production run between 1931 and 1935. The smaller Arrow was axed in 1933 after just 3 years production, although the model sold 1,500 in its first year.

A local Hawk

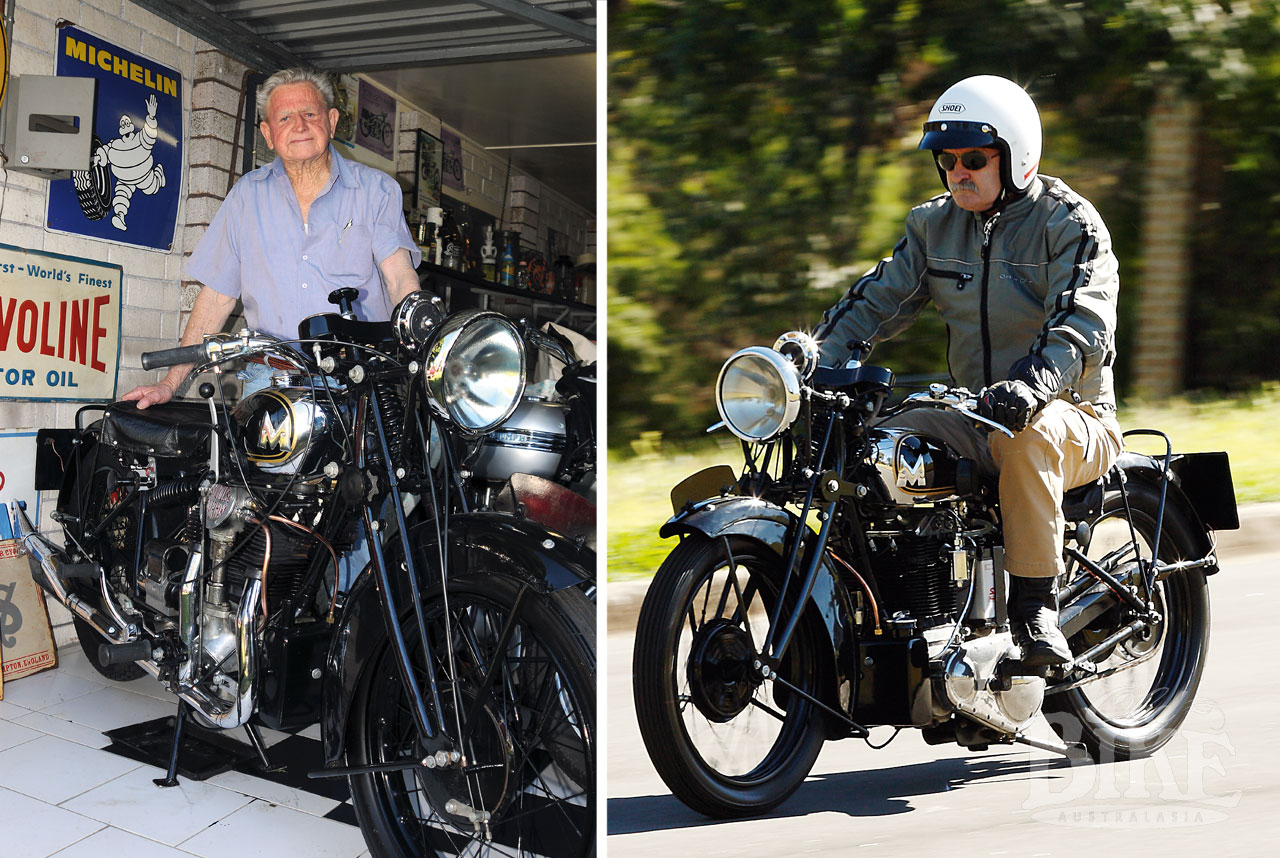

Given the very low numbers that actually found buyers, Matchless Silver Hawks are not exactly thick on the ground today, especially in Australia. Ivan Casson, a man with a soft sport for the flying M, has a Silver Hawk in his collection, which also includes a Silver Arrow vee-twin, a 1934 X-3 Vee-twin, a rare 1953 G9 which, because of the nickel shortage due to the Korean War has an all-black tank and anodised wheel rims, a 1950 G80 rigid in completely original condition, and a couple of AJS badge-brothers in a Model 20 Spring Twin and an ex-Sammy Miller 16CS Trials model. His X-3 is an ex-London Police model, which has footboards fitted in place of the normal footrests.

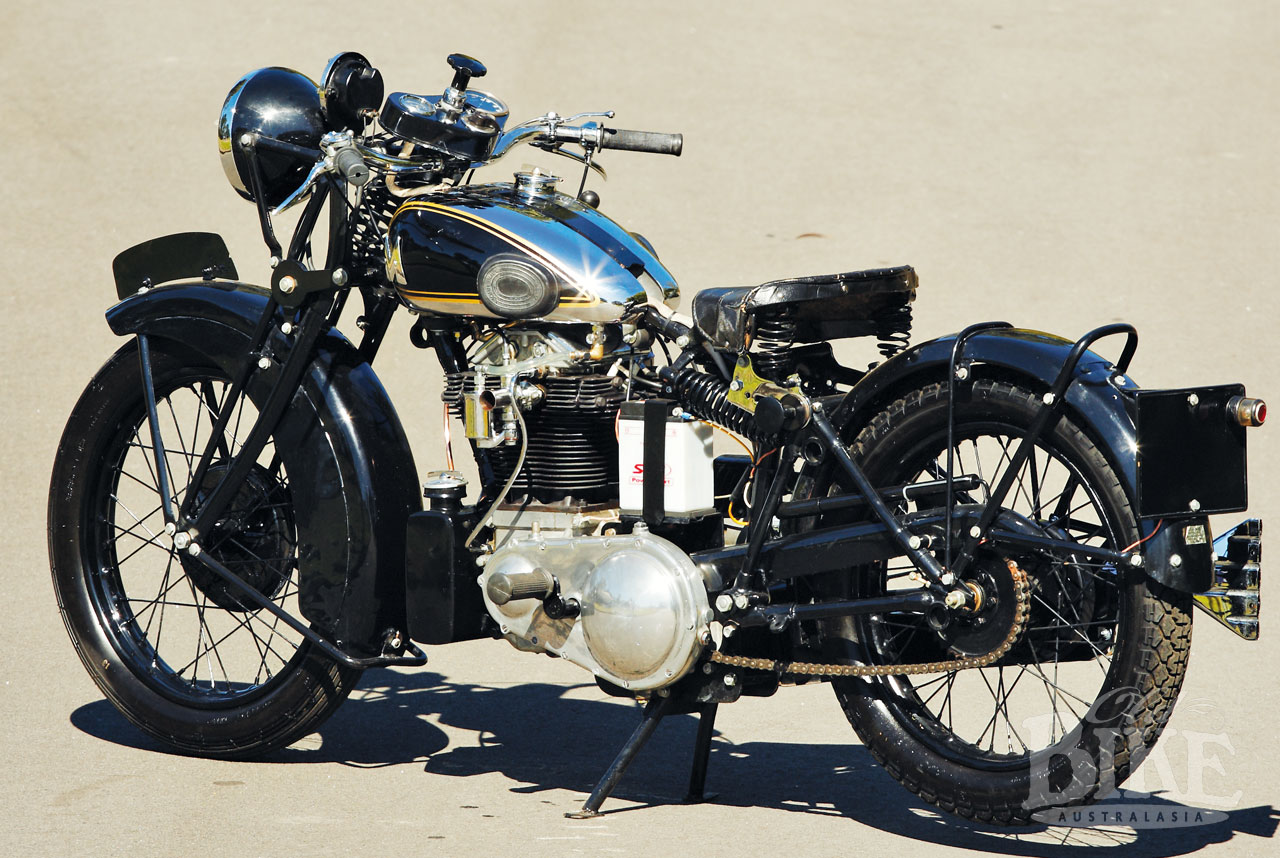

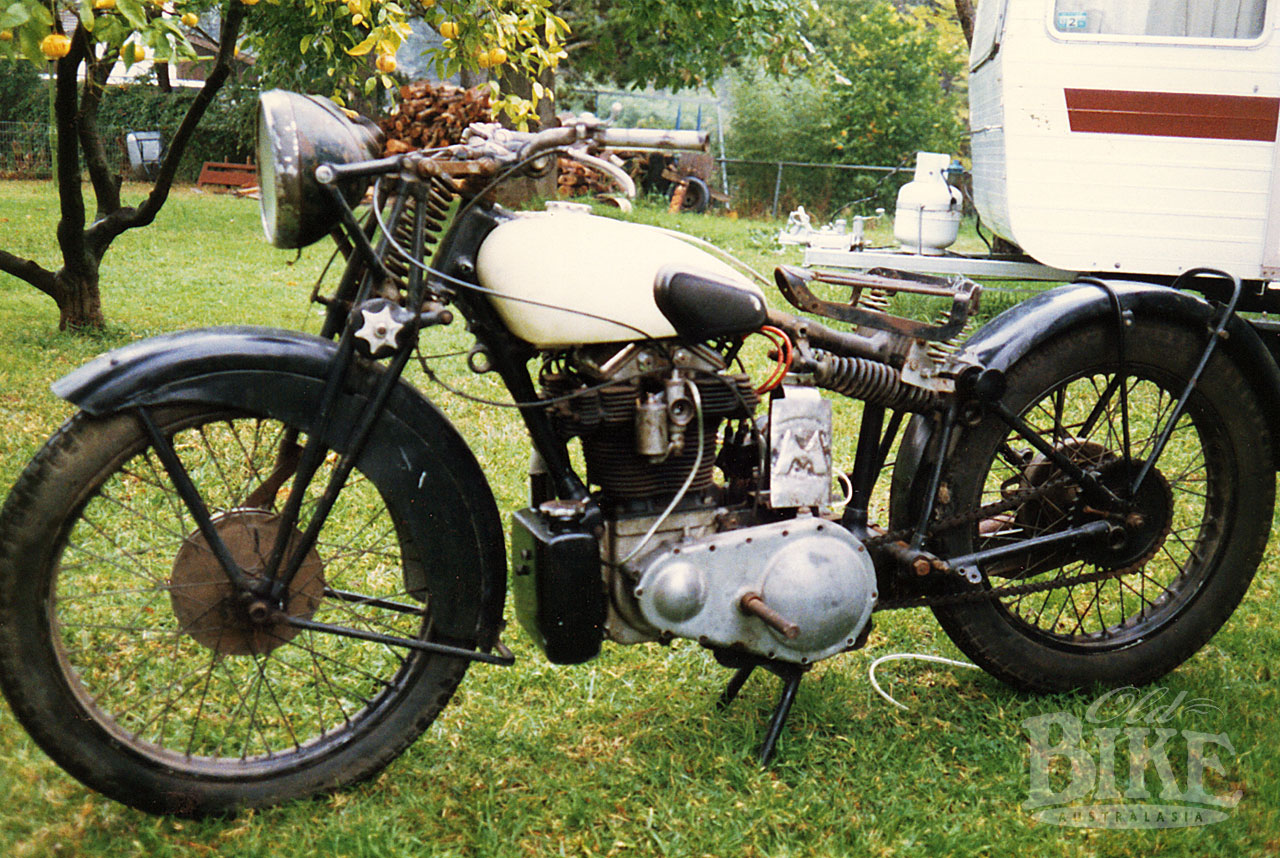

Ivan’s Silver Hawk was originally sourced from a property in Western Australia, and came to Sydney via the long-established classic motorcycles dealer Barry Graham. It was no thing of raving beauty at the time, with many parts incorrect or missing completely. The original owner had fitted a set of Ariel forks for some reason, but fortunately had kept the Matchless forks, which came with the bike. It lay under Ivan’s house in western Sydney for several years, with Ivan undertaking the odd job himself, and Ivan would occasionally kick start the Hawk so his mates could hear the unusual engine note. It was unusual for a very good reason, as it turned out.

A 1931 hand-change model (later versions used a foot gear change), the Silver Hawk was missing a few niggling bits like the wingless tank badges (which Ivan turned up at a swap meet), the correct muffler, and one tank knee pad, which was located, remarkably, at Max Eade’s shop in Ashfield. Realising that doing the work to restore the Hawk was probably beyond him, Ivan entrusted the work to Mick Dyer, who has done an excellent job, and also solved the mystery of the unusual exhaust note. “As soon as Mick started the bike, he knew something was wrong,” explains Ivan. “It was actually only running on two cylinders, so Mick pulled the distributor off and found it only had two lobes on the camshaft – so it could never have been running on four cylinders, at least with that distributor fitted! Mick welded and machined extra lobes on the distributor camshaft, and away she went – a four cylinder again.” The only other Silver Hawk in Australia that Ivan is aware of was part of the Keith Williams collection on Hamilton Island. “I drove up to Coolangatta to look at the Silver Hawk prior to the auction when Keith’s collection was sold off, but it had a lot of non-original parts like exhaust pipes. It went for $17,000 at the auction,” he recalls.

As recently as November 2009, it became evident that another Silver Hawk was indeed around these parts, when Stan Cleary’s beautifully restored example appeared at the National Jampot Rally in Goulburn, and not surprisingly galloped away with the top award. (See the rally report on page 84 of issue #17).

Throwing a leg over

Some years ago, I had seen the Silver Hawk under Ivan’s house and expressed a desire to see it again when the restoration was completed. In 2007 I visited the excellent Solvang Museum in USA which has a Silver Hawk (also a hand-change model) but more time passed and I had almost forgotten about the local example when Ivan called to say it was a complete runner again and would I like to have a ride on it? Would I! A few days later I arrived with helmet and jacket and was immediately taken with the quality of the restoration, at least externally. “The inside of the engine hasn’t been touched, but Barry Graham told me he had checked it all over. Mind you, that was back in the early 1980s,” Ivan said. Nevertheless, the Hawk fired up after a couple of kicks and sat there idling and clattering happily, albeit a bit on the rough side. There’s a fair bit of bike under you when you take the saddle, and hand-change machines always take a bit of coordination to get under way. The engine note is quite unique – unlike a vee-twin or four and probably more like a parallel twin of typically British extraction.

In fact, the engine didn’t seem particularly happy during the short time I rode it, and the bike is due to be returned to Mick Dyer for an internal revamp to the same gleaming standard as the external. I can imagine that once correctly fettled, the Silver Hawk would be a magnificent rally bike, smooth and with adequate power, and certainly a real head-turner at any gathering. I have been promised a return visit once the rebuild has been completed, and I am eagerly looking forward to it, but even with the teething problems, the Silver Hawk is an astounding example of the type of thinking that was happening in certain sections of the British motorcycle industry in the 1930s. In the official publicity surrounding the Silver Hawk’s release in 1931, Matchless said, “ The Silver Hawk is unquestionably the most fascinating machine to ride that has ever been built. It combines the silence, smoothness and comfort of the most expensive motor car with a super-sports performance. In top gear alone the machine will run from as low as 6 miles per hour, while the acceleration given by the four-cylinder overhead camshaft engine in conjunction with the four-speed gearbox must be experienced to be believed.” Strong words indeed.

Certainly, the specification for this machine makes the subsequent post-war fare of singles and twins seem quite bland by comparison, and the Silver Hawk remains a classic example of an age when designers were permitted carte blanche.

1931 Matchless Silver Hawk – Specifications

Engine: 592 cc 26º V-four single overhead camshaft

Bore and stroke: 50.8 x 73 mm

Production: 1931- 1935

Gearbox: Sturmey-Archer 4 speed.

Top Speed: 76 mph.