In the early 1950s, the Ultra Lightweight class was a hot-bed of two strokes, but one hand-built DOHC model could run with the best of them.

The story of the Hunter Piccaninny really has to begin with the story of Ron and Murray Hunter, from Oakleigh in Melbourne. The brothers were both keen competition riders and skilled engineers, and their workshop prowess benefited many a rider in early post-war racing. Their most prominent product was the Hunter brake – front and rear heat-treated aluminium-alloy conical hubs, not unlike KTT Velocette items, fitted with twin-leading shoe operation. Distinctive in appearance with their five gauze-covered windows spaced around the conical surface of the drum, these brakes were praised for their light weight and excellent stopping power and were seen on many successful machines, although today you would be hard-pressed to find one. Ron Hunter, the elder brother, became president of the energetic Hartwell Motor Cycle Club in the late 1940s and was also a very competent rider in scrambles, road racing and grass tracks. It was in the latter discipline that he lost his life in December 1950 while competing at Nar Nar Goon on a Mk8 KTT Velocette. His death was a huge loss to the motorcycling community, and Hartwell Club renamed their annual scrambles event the Ron Hunter Memorial Grand National, which grew into Victoria’s most prestigious such event in the years to come.

In 1944, Ron had used his engineering skills to heavily modify a KSS Velocette, reducing the capacity to 250 cc and winning the 1945 Victorian 250 cc Scramble Championship, and in 1946, the Victorian Hill Climb Championship. Spurred on by this success, Ron constructed a special 250 cc DOHC engine with 68 x 68 mm bore and stroke, using his own crankcases with roller bearings on each side. The cylinder was turned from a solid billet of Duralumin, with a Hunter-made piston giving 12.5:1 compression for petrol-benzol. To drive the camshafts, a bevel-driven nickel-chrome hollow vertical shaft was used, running in self-aligning ball races and driving a train of five spur gears. Twin gear-type oil pumps, housed in the Velocette timing chest, supplied lubrication. A 1-inch Amal TT carburettor was fed by a float chamber of Hunter’s own design. Gearbox, clutch and frame had origins in a MAC Velocette, while AMC Teledraulic front forks were fitted. Power output was reckoned to be 27 bhp at 8,500 rpm. The 2.75 gallon fuel tank was hand-beaten from 22-gauge sheet steel segments welded together, and narrowed sharply at the rear to allow the rider’s knees to be tucked well in. All non-alloy parts, including the frame and fuel tank, were cadmium plated giving a very unique appearance.

Murray Hunter gave the 250 its debut in 1949 for the Victorian TT at Fishermen’s Bend, with Ron in the saddle for subsequent meetings at the same venue in January 1950 and at Ballarat Aerodrome later in the year.

At the time of Ron’s death, the brothers had a number of projects on the drawing board, including a 125 cc double overhead camshaft four-stroke single, for which much of the preliminary work, including drawings, patterns and some castings had been done. The plan was to build a batch of three engines. Murray had plenty on his hands after taking over Ron’s engineering business, but rather than abandon the 125 project, he pressed on, determined to see the design through to completion in memory of his brother. It was very much a trial-and-error process, because although the design had been sketched out, the intricacies of actually getting such a design to function under racing conditions was a completely unknown quantity.

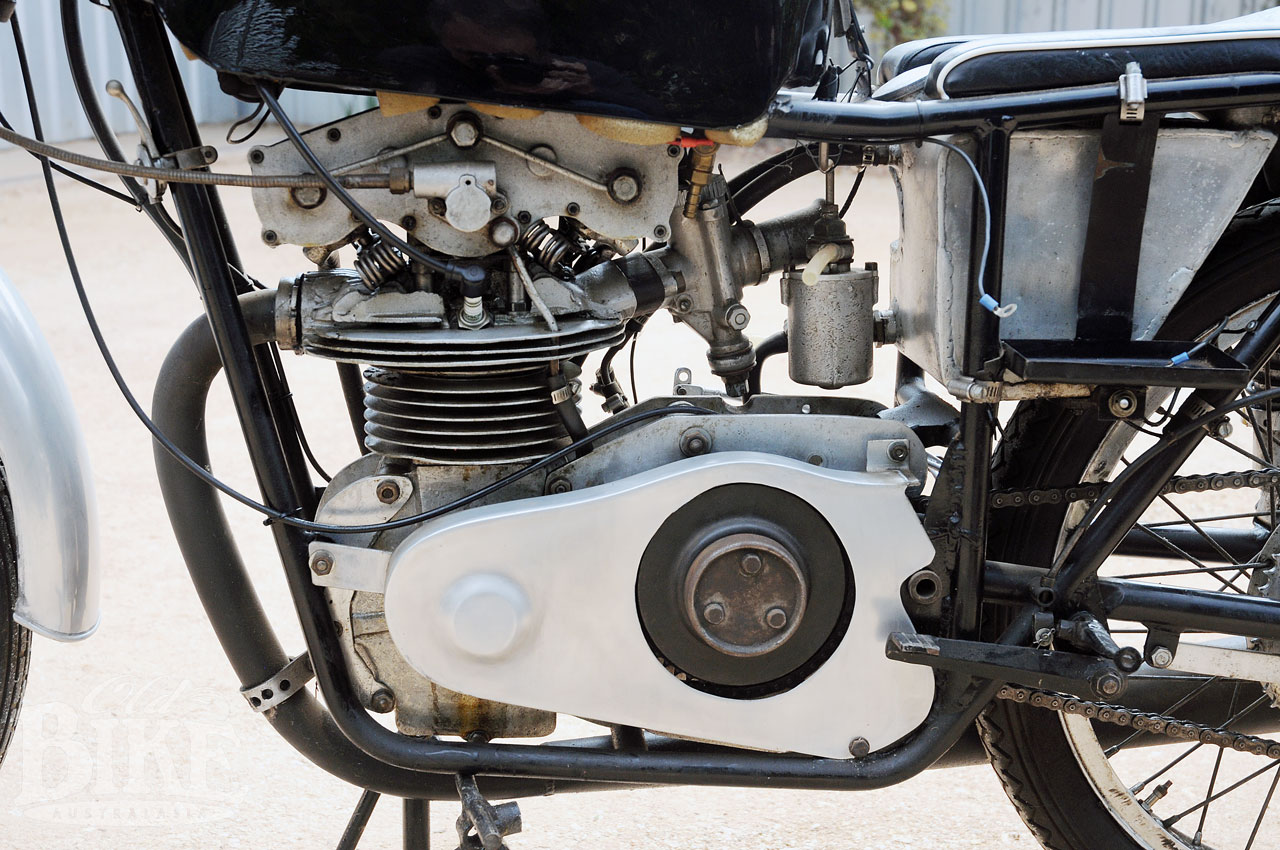

The alloy crankcases and cast-iron flywheels were designed and machined in the Hunter workshop, mostly after business hours when the day-to-day general engineering work was completed. The big end assembly came from a MOV Velocette, with 22 mm main bearings and a hand-forged conrod made from 90-ton steel. The alloy cylinder with cast-iron liner was also made in-house. Inside the hemispherical head were two 1.25” valves made from KE-965 steel, controlled by hairpin springs. Compression ratio for petrol was 10.5:1. The camshafts, which were housed in separate cylindrical chambers, were chain-driven from the mainshaft, with the chain running in a neat alloy chest. Originally an oil pump from a 250 cc BSA was used, but was later modified with an extra scavenger pump. The 4-speed gearbox and clutch were by Albion.

The frame was built up from sections of a New Imperial, with MOV girder forks, while the plunger rear end was Murray’s own design, with covers from a Jawa. Tyres were 2.75 x 21 from and 2.75 x 19 rear. Scaling in at 198 pounds (90 kg), the Hunter Special was capable of 94 mph, at which point the little engine was spinning to 11,000 rpm.

Bathurst at Easter 1952 saw the 125 Hunter’s debut, where it was ridden by Jock Johnson. It completed several practice laps and showed a respectable turn of speed, but failed to make the grid for the 4-lap 125 cc race which was convincingly won by Maurie Quincey on the Walsh Bantam BSA. Later in the year it appeared at Fishermen’s Bend and at the Australian TT at Little River, ridden by Bruce Cameron.

Around this time the Hunter 250 was sold to Sandy Maxwell, who took it to England. During the 1954 season, Victorian Ivan Tighe rode the Hunter in two meetings in Europe – at the formidable 20.8 km Nurburgring and at Floreffe in Belgium, where he scored a fine fourth place in the 250 race behind three works machines – before it was sold to a Mr E. Smith of Derby in the English Midlands. Whether it is still there is unknown.

Murray Hunter had never been particularly impressed with the performance of the 125 cc model, which was unceremoniously scrapped, and began again from scratch of a new DOHC design. Years later, Murray recalled, “ I decided to make a 125 DOHC motor and bike complete, which took me three years to finish. All the patterns were made in our little shop and machined on an old lathe and milling machine. After many headaches the bike was finished and to my surprise it turned out to be quite good.”

This was a far more modern looking job, with bevel drive instead of chain drive for the camshafts. With its black petrol tank, seat base and rear mudguard, it became known by the now politically incorrect team of the Piccaninny (from the Spanish pequeno, meaning small, and usually applied to black children). The Hunter Piccaninny used ‘square 54 x 54 bore and stroke, 12:1 compression ratio, MV Agusta hairpin valve springs, and vernier timing on the gear wheels to the camshafts which ran on ball races. Valve sizes were 1 9/32” inlet and 1 3/8” exhaust, with a 15/16” GP carburettor. The one-piece crankshaft was made from R5 steel with a nickel chrome crankpin and a conrod hand-forged from Vibrac. The high-tensile alloy piston was made by the Chamberlain company in Melbourne, famous for its tractors and racing cars. Ignition was total loss, with a large capacity Bosch battery and a Hunter-built points assembly. Murray obtained a set of Armstrong leading link front forks which had been sent to Australia for display at motor shows and had a section cut from the left side to show the internal springs. A cover was made up and brazed over the hole. At the rear, a set of spring dampers was constructed using HRD shock absorbers as the basis. The gearbox and clutch from the first 125 cc Hunter was employed, with the internal gears made by Hunter, and the engine and transmission housed in a very neat double cradle frame, similar to a Norton Featherbed, but made from tiny 7/16” aircraft tubing. As before, the Hunter twin leading shoe brakes were used, with 2.50 x 19 Avon Racing Tyres front and rear. Dry weight is 175 pounds (79.5 kg).

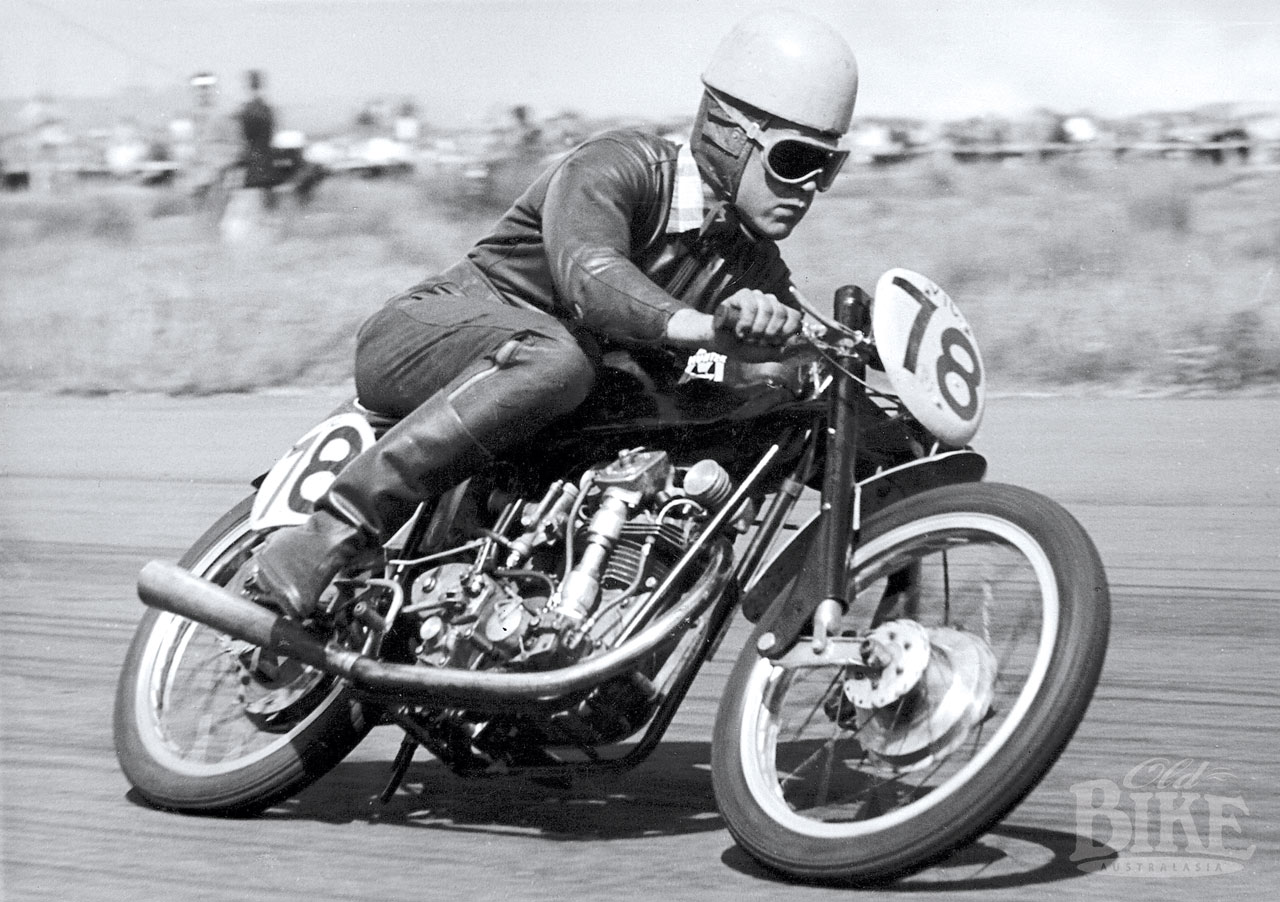

The race debut for the ‘Piccaninny’ was at the new 1.3 mile circuit at Port Wakefield, South Australia, in October 1956 and it couldn’t have gone better. With George Huse in the seat, the new 125 thrashed the opposition, consisting mainly of locally built Tilbrook two strokes, leaving Alan Wallis, R. Crowell and Rex Tilbrook well behind the howling little four stroke after eight laps. 1956 finished well with Huse taking the Piccaninny to second place in the Australian TT at Mildura, on Boxing Day, although he was well behind winner Don Cameron on the Walsh Bantam. Two months later Huse scored another second place, this time in the Australian Grand Prix at Bandiana, behind Roger Barker’s MV Agusta. Murray Hunter said that the Piccaninny was timed at 89 mph on the long Mildura straight, whereas the Walsh Bantam recorded 97 mph – a major speed deficit that proved difficult to overcome.

At Bathurst at Easter, 1957, George Huse fronted for the 125 cc TT on the Piccaninny, one of the few four strokes in a sea of Bantams, and put in a solid ride to third place. While the Walsh Bantams of Ken Rumble and Don Cameron battled for the lead, Huse overhauled the fully-streamlined ex-works Lambretta ridden by Vince Tierney to make it a Victorian 1-2-3 at the finish. 1958 didn’t produce any results at Bathurst, but one year later the Hunter team was back, and again took third place in the 125 GP, this time behind Noel Gardiner on the Walsh Bantam and Roy East on Clem Daniel’s MV Agusta. A few months prior to the Piccaninny’s Bathurst swan song, Huse had taken the machine to an emphatic victory in the Victorian Grand Prix at Phillip Island on New Year’s Day, 1959.

But the writing was on the wall for everyone in the smallest class, as the new Honda twins began their takeover from the following year. The Piccanniny, like the previously all-conquering Bantams and even the exotic MVs, were outclassed, and soon discarded in favour of the Japanese machines. The Hunter Piccaninny disappeared into the shed for several years, before it was eventually acquired by Charlie May, the great all-round rider and motorcycle dealer from Casterton in Western Victoria, around 1966. Subsequently, the Piccaninny broke a conrod and a Montesa engine was fitted to the frame, and Charlie’s son Peter rode the Hunter in this form at McNamara Park, Mount Gambier. About 1975, another Casterton family, the Millers, bought the Hunter in a job lot that included a 1935 Mk4 KTT Velocette, a Mk1 KSS Velocette, and a Norton International. The Piccaninny passed to one of the Miller boys, Alan, who was completing his medical degree in Melbourne and moved to set up practice at Waikerie, in South Australia’s Riverlands district in the mid 1980s. Apart from the damaged engine, the bike was totally original, down to the Avon tyres, and Alan set about the task of making it a runner again. Sourcing the correct material for a new conrod wasn’t easy, but once located, one was made up by Melbourne engineer Bob Abbey. The barrel had been savaged in the blow-up, but fortunately another barrel and piston came with the spares.

Apart from the fibreglass front number plate cowling, the Piccaninny is in the exact specification that it was when raced so successfully by George Huse, and is once again ready to run. Alan Miller has plans to retire from the medical profession in the not too distant future, and this will give him more time to devote to his collection of bikes and cars, something he is very much looking forward to. If things work out, Alan hopes to bring the Piccaninny to the 2011 Honda Broadford Bike Bonanza next Easter, where it is sure to be a major attraction. Certainly, the little black bike is a landmark in the annals of Australian motorcycling history – a classic example of the skill, ingenuity and dedication of Murray and Ron Hunter and engineers like them who created such works of art.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook with assistance from Brian Guthrie • Photos: Keith Ward, John Carter, Bo Eklund, Charles Rice.