From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 72 – first published in 2018.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook • Ride impressions: Rennie Scaysbrook

While its rivals stuck with the near-ubiquitous in-line DOHC four cylinder engine, Honda had a long-term investment in the V-4 layout, and refused to submit. But it came at a cost – a big cost.

The motorcycle that was created to win the World Superbike Championship – and succeeded in 1988 and 1989 – the Honda RC30, was, after six years, getting a bit long in the tooth. By 1994, something was needed to stay with the likes of the Ducati 916, the Kawasaki ZX7-R and soon, the Suzuki GSXR-750. That something was the RC45, or the evolution of the RVF750 if you prefer.

Honda built just enough of these – 200 – in the 1994 (only) production year, to qualify for the championship, and over the next five years a handful more trickled out to keep the various teams around the world supplied. It took until 1997 for John Kocinski to achieve the Honda factory’s aim of wrestling the World Superbike Championship from Ducati, but the RC45 made a winning debut three years earlier at the 1994 Isle of Man TT when Steve Hislop, Phillip McCallen and Joey Dunlop gave the works-supplied UK Castrol Honda team a resounding clean sweep of the podium in the Formula One TT, followed later in the week by an identical result in the Senior TT. Indeed, with the only works squad in the event, Honda UK and the Castrol RC45s would dominate the TT for the next five years. Out in the colonies, Anthony Gobert gave the RC45 a dream debut at the wet Phillip Island round of the Australian Superbike Championship, and continued his form to become (at 19) the youngest-ever winner of the title after a season-long battle with the Kawasakis of Martin Craggill and Matthew Mladin. The following year, Kirk McCarthy took over the Winfield RC45 and won the title from Mladin.

In the UK, the RC45 carried a price tag of £18,300, or about the same price as the Ducati 916SPS and Bimota SB7. That became $35,000 in Australia, but the promise of a works racer that was available to the public was very tempting for those sufficiently well-heeled to consider placing an order. The reality was somewhat different. While the race bikes were bedecked with exotic suspension, wheels and other fitments permitted under the formulae, the RC45 sold to the public was more prosaic. The front forks, for example, were similar to the CBR600 with 41mm tubes, which were on the puny side by the standards of the day. The front hoop was a 16 incher – specifically a 130/70ZR16 – that by 1994, was also somewhat passé, with the opposition all running a 17 inch front, and a curious choice given the rear tyre was a 190/50ZR17. Switchgear was sourced from the Honda CBR900. Indeed, the existence of the CBR900 Fireblade was somewhat of an embarrassment to Honda, as this relatively simple (and affordable) in-line four could give the RC45 a serious run for its money.

The RC45 is inevitably compared to its forebear, the compact and nimble RC30, but in appearance at least, seems bigger all round. Whereas the RC30 perched its rider over the front, the riding position on the RC45 is more relaxed and contemporary. The seat height is 50mm lower, as is the centre of gravity, which was central to Honda’s aim to get the new machine to turn into corners with more precision and less rider effort.

From the beginning of Honda’s V-4 series – the VF750S of 1972 – bore and stroke had been consistent at 70mm x 48.6 mm, but the RC45 broke with tradition with a bore of 72mm and a stroke of 46mm. As on the RC30, titanium connecting rods were used, but the cylinder bores were now of what Honda called ‘metal composite’ – a ceramic-blended aluminium that could be rebored if required. The process saved an impressive 1.4kg. In the cylinder head, valve angles were reduced by a total of eight degrees. The signature gear-driven camshafts were retained in the RC45, but moved from the centre to the right side of the engine, which permitted a shorter crankshaft – and more weight saving – plus a straighter passage for the inlet tracts. The most visible change between the 30 and the 45 was in the use of a radical fuel injection system that had been developed on the exotic oval piston NR750. This used 46mm throttle bodies instead of the 38mm Keihin carbs with a total of seven sensors to deal with mixture control.

Chassis-wise, the RC45’s twin-spar aluminium frame used thinner wall frame members than the RC30, supposedly to engineer more flex into the unit, although the external dimensions were larger. The frame itself was built around a large diameter cast-alloy steering head. Although the new machine looked larger, the wheelbase was only 5mm longer, courtesy of a longer swinging arm. The swinging arm itself was once again the Elf-patent single-sided unit, controlled by a fully-adjustable gas-charged shock absorber that owed much to the company’s successful motocrossers. At the steering end, the forks provided 24.5 mm trail and 92mm rake. While the RC30 used hand-laid fibreglass for the fairing, the RC45’s bodywork was in plastic. More weight saving.

With 120 hp at 12,000 rpm on tap, the standard RC45 was hardly a slouch, but an extra 30 hp was available to those who wanted to go serious racing, and could afford it. And make no mistake, some serious coin was required to make the RC45 competitive. For this reason, few privateer teams opted for the Honda, when there were several choices available from rival manufacturers at a substantially lower cost. The genuine HRC kit parts included bodywork, wheels, front forks, rear shock and linkage, clutch, complete swinging arm, engine covers in magnesium, and sundry smaller items. Price? Best not to ask.

Early tests of the RC45 gave journalists plenty to think about, with the inevitable comparison to the RC30. Most agreed that the most endearing characteristic was the glorious sound – Formula One on two wheels. The snarl emanates from beneath the tank with vast amounts of air rushing in, although the tunnels running from the front of the fairing to the fuel tank top are largely cosmetic. The close ratio gearbox made it a chore around town; the tall first gear requiring a handful of revs in order to pull away cleanly, and judicious use of the gearbox in traffic. But the RC45 was hardly designed with traffic in mind, except perhaps, lapped traffic. Low, steeply angled handlebars bars were also uncomfortable around town but perfect for the open road.

The engine was also somewhat cold blooded and needed warming up so the temp gauge showed at least 70 degrees before riding off. The choke knob mounted on the left fairing inner is actually nothing more than a fast idle lever, as the extra richness a cold motor demands is catered for by the Programmed Fuel Injection system (PGM-FI) lifted from Honda’s technology showcase, the NR750. This is fed information from seven sensors measuring critical parameters such as intake air temperature, barometric pressures, and engine rpm, and then supplies the right quantity of fuel ignited by a spark at the optimum moment.

In the saddle with Rennie Scaysbrook

I had a poster of the RC45 all through my high school years. It’s a bike I’ve lusted over, and dreamed about, never thinking I would get the chance to even sit on one, let alone ride one. For me, the RC45 is a mythical machine, steered by legends like Slight and Edwards, and I’ll admit I was scared it would disappoint in a “don’t meet your heroes” kind of way. I’m glad, this time, I was wrong.

There are several highlights when riding an RC45, but none, absolutely none, tops hearing that gear-driven cam V4 at full song. It’s a flat, droning roar, so far removed from any V4 since this bike came to market in 1995 for a lucky 200 riders. But there’s a problem with the 45 in that Honda was greedy. The power is underwhelming and the motorcycle’s weight excessive—Honda would supply the RC45, but it was up to the respective owner to purchase various HRC kits to really make them fly—hence why so many privateers went for a Suzuki or Kawasaki for a fraction of the cost.

Despite the lack of outright power, the motor is incredibly smooth in its delivery for a bike with a primitive 25-year-old fuel injection system, and the gearbox, with its short throw and close ratios, is how a superbike ’box should be. There’s no getting away from the fact the RC45 is heavy, and you sit very low in the chassis. It’s heavy but easy to change direction on and extremely stable at speed, although at traffic speed you’re not even scratching the surface of what this thing can do.

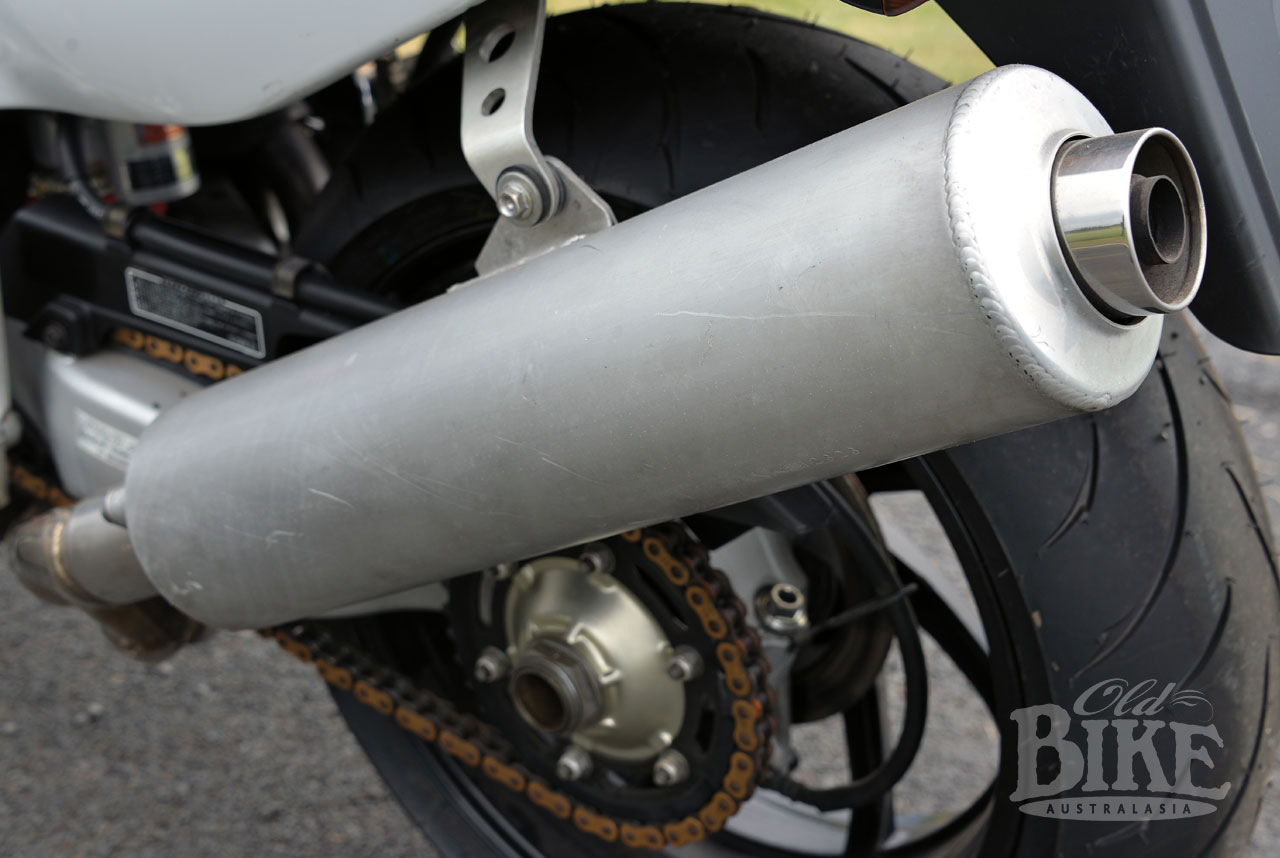

Another highlight comes in the form of the dash. The twin analogue tacho and speedo is from a totally different age to what we’re used to today, the revs sweeping up almost in unison with the speedo and the crescendo of noise from the single outlet exhaust, it’s as 1990s as hypercolour t-shirts and Nirvana.

The RC45 is not today-level fast. A modern 600cc Supersport would annihilate it. But the RC has a presence about it today’s bikes can only dream of. A genuine, homologated racing motorcycle from the biggest company of all, the Honda RC45 may not have reached the racing heights demanded of it, but that doesn’t make it any less special. I’d still have one—in an instant—if only to hear that beefy, menacing drone from that gear-driven cam V4.

Specifications: 1994 Honda RVF750 (RC45).

Engine: 90-degree, 16-valve, vee four, liquid cooled, gear-driven DOHC

Bore x stroke: 72mm x 46mm

Capacity: 749cc

Compression ratio: 11.5:1

Ignition: Computer-controlled digital transistorised with electronic advance

Fuel: PGM-F1 fuel injection with 4 x 46mm throttle bodies.

Lubrication: Wet sump.

Transmission: six-speed gearbox, gear primary drive, chain final drive, hydraulically-actuated diaphragm spring clutch.

Frame: Aluminium perimeter type with extruded triple-box spars, bolt-on alloy subframe, single-sided Pro-Am swingarm.

Wheelbase: 1410mm

Suspension: Front: 41mm telescopic Showa upside-down fork. Adjustable preload, and compression and rebound damping. 120mm travel. Rear: Gas-charged Showa monoshock with integrated reservoir, adjustable pre-load, compression and rebound damping, adjustable ride height, 130mm travel.

Wheels/tyres: Front: six spoke cast alloy 3.5 x 16 inch. Dunlop D204 Sportmax II radial 130/70 ZR16. Rear: eight spoke cast alloy 6.0 x 17 inch. Dunlop Sportmax D204 radial 190/50 ZR17.

Brakes: Front: 2 x 310mm floating discs with 4-piston Nissin calipers. Rear:1 x 220mm floating disc with 2-piston caliper.

Dry weight: 189kg

Fuel capacity: 18 litres

Seat height: 770mm

Max power: 120ps at 12,000 rpm

Max torque: 7.7kg-m at 10,000 rpm

Max speed: 260 km/h

Price: $35,000 Australia (1994)