Story: Rennie Scaysbrook • Photos: Kit Palmer, Jim Scaysbrook

To be fair, Blind Freddie could have recognised the RC30 as an instant classic from the moment it made its public bow. It’s a prime example of what Honda does from time to time; create something with a single purpose in mind, and spare no effort or expense in doing so.

In this case, the single purpose was to win the inaugural World Superbike Championship in 1988, which it (narrowly) achieved thanks to Fred Merkel’s skill and a small degree of luck. But a win is a win, and a championship – a World Championship, thank you – is even better, and Honda’s svelte V4 had earned its stripes in consummate fashion, although Merkel actually won only two of the sixteen races. Just to rub it in, Merkel swept to a second consecutive – and far more dominant – World Championship the following year on a developed version of the same machine. In fact it was a Honda RC30 1-2, with Belgian Stephane Mertens filling the runner up spot to the flamboyant American.

But the v-twins, they were coming, and perhaps with rules tweaked to favour, or at the very least encourage the European factories, Ducati began its rise to supremacy, something that miffed Honda into a severe re-think of the RC30, resulting in the fuel-injected RC45. But that is another story, and here we shall concern ourselves with a period in history that began in 1987 when the first batch of VFR750R Hondas was released to a slathering audience in Japan. Such was the machine’s instant charisma, and such was the effect of the carefully manipulated pre-release marketing campaign that decreed the new V4 would be available only to selected dealers in strictly rationed numbers, queues formed outside dealerships, and if you believe the folklore, scuffles broke out amongst queue-jumpers!

The Before Machines

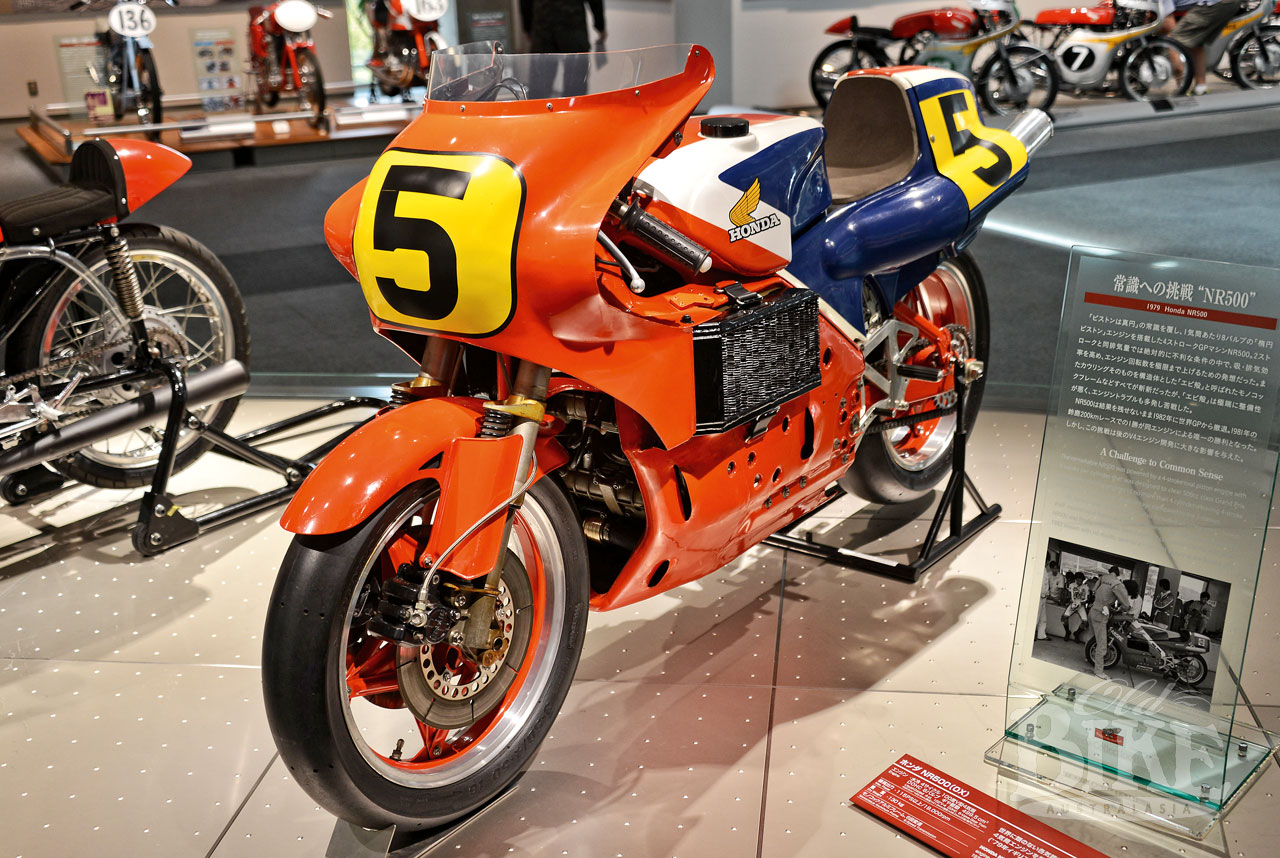

Curiously, the V4 Honda concept was not exactly covered in glory by the time the RC30 broke cover. The V4 had its origins in the ill-fated NR500 project of 1979/80, and in 1982 along came the VF750S – a liquid cooled 90º V4 with 70 mm x 48.6 mm bore and stroke making for an extremely compact unit that was just 414 mm wide. The engine featured horizontally-split crankcases, with a one-piece, four bearing crankshaft. The 360º crank meant the two rear pistons rose and fell simultaneously, as did the front pair. The twin overhead camshafts, driven by a Hy-Vo chain from the crankshaft’s centre, operated four valves. Compression ratio was a relatively high 10.5:1. Two models, both shaft driven, were offered; the cruiser-style Magna with conventional twin-shock rear suspension, and the single-shock Sabre. But from the outset, problems plagued the design, ranging from irritating stuff like erratic idling to much more serious issues like premature camshaft wear and transmission glitches.

From this difficult birth evolved a much better machine, albeit one that had its own set of problems – the VF750F, also known (in USA) as the Interceptor, where a new set of regulations set the top capacity limit for Superbike racing at 750cc. In an effort to shorten the rangy wheelbase, the engine was tilted backwards by 15º, while the shaft final drive was ditched in favour of chain. Curiously, the transmission went from six ratios to five, but incorporated an early version of the slipper clutch to make down-changing at high rpm a less fraught affair. Also ditched was the VF750S rubber mounting system for the engine.

The most radical departure however, was the chassis; a full-cradle design in square-section steel, with a cast aluminium swinging arm operating Honda’s Pro Link single-shock rear suspension. Up front was another first for a production bike – a GP-style 16 inch front wheel, with an anti-dive system (known as TRAC) operating on one fork leg. Australian models received gold-anodised Comstar wheels, and brakes were specially-made Honda/Nissin twin-piston calipers on ventilated discs. Despite the attention to detail, the bike was heavy for a 750, tipping the scales at 221 kg. There was much jubilation in Honda circles when Malcolm Campbell and Rodney Cox took out the 1983 Castrol Six Hour Race at Amaroo Park (Honda’s first win in the prestigious race since 1971), with Rob Phillis and Geoff French on another VF750F in second place.

But still there were quality control problems, particularly in the top end, with camshafts continuing to wear out at an alarming rate. Honda worked hard on modifications to the lubrication system that largely cured the problems, but the word spread that the bike was a dud and sales followed suit.

Still, Honda pressed on with the V-4 concept, releasing a whole range of new models in 1983 that included the VF1100C (actual capacity 1098cc) and the VF400F, the latter designed to snatch some of the market held by Yamaha’s liquid-cooled RD series two strokes. The 400 was soon joined by the VF500F, which quickly gained a reputation as the best of all the V-4s so far. At the other end of the range came the new and stylish VF1000F, and for the sporty set, the VF1000R, with gear-driven overhead camshafts. Designed to further the impetus created by the three models of the successful CB1100R, the new VF1000R really missed the mark, being far too heavy, enormous in appearance and with less than adequate suspension, especially in view of the incredible capabilities of the 122 hp engine.

By 1984, Honda was beginning to take serious interest in the Endurance Racing concept that was sweeping Europe, as well as the blossoming British TTF1 series, and their RS750R, based on the VF750F used in US Superbike racing, was the result. The Endurance racer developed into the RVF750, with 135 hp on tap, and with Wayne Gardner in the saddle, brought Honda a cherished victory in the Suzuka 8 Hour Race in 1985, plus top spot in the World Endurance Championship.

Honda was winning on the race track, but still sales of the road-going V-4s were sluggish. In an effort to gain some reflected glory from the numerous championship wins, the VFR750F was created – a far better machine than its predecessors but still under intense competition from its Japanese rivals – which soon gave way to a completely redesigned model with a much lighter engine with 180º crankshaft (supposedly producing improved exhaust scavenging) and gear-driven camshafts. The chassis was all-new too; a box-section aluminium frame and similar swinging arm; the machine now weighing it at a very competitive 198kg.

Gestation Period Over

Which more or less brings us to the point of the story – the VFR750R or RC30. While the RC30 was technically based on the latest evolution of the VFR750F, the resemblance was superficial, the attention to detail reflecting the fact that every RC30 was built by a small team of dedicated technicians at the Honda Racing Corporation. Beginning with the power plant, the major difference was the reversion to a 360º throw for the crankshaft, upon which sat titanium con-rods – the exotic material also used for the valves. Camshafts ran in needle-roller and roller bearings, acting directly on the valve stems; the elimination of rocker arms allowing for a more compact cylinder head casting and for the inlet ports to be realigned by tilting 6º higher to produce a more direct path from the carburettors to the combustion chambers. The standard 38º included angle for the valves was retained. No oil cooler was fitted, but oil temperature was reduced by running engine coolant through a small circular radiator mounted adjacent to the oil filter. Two large radiators (one with fan assistance) carried the engine coolant.

Chassis-wise, the RC30 was closely based on the aluminium twin-spar RVF750 with what Honda called the Diamond frame concept which used the engine unit as a stressed member. The RVF had made good use of the Elf-patented single-sided swinging arm (Honda paid a royalty to the French fuel company for each item produced) with the wheel retained by a single nut which allowed rapid wheel changes where the rear sprocket and chain remained in place, and the RC30 retained this feature. Interestingly, even though the wholesale transition to front and rear 17-inch tyres was under way (which would subsequently render the formerly universal 18-inch hoops obsolete and largely unobtainable), the RC30 employed an 18-inch rear with a 5.5 inch rim, supposedly as it offered marginally better wearing qualities, another crucial factor in Endurance racing. The rear brake set up incorporates a linkage connecting the caliper to the chassis, claimed to reduce ‘squat’ under braking and acceleration.

Up front, provision for rapid wheel changing was also evident. Each fork slider actually swivels inside the top mudguard mount to allow the calipers to clear for easy servicing, while a single nut on the bottom of each slider operates a hinge that allows the wheel to simply drop out.

A shapely aluminium fuel tank with a quick-fill cap was used and each fibre glass fairing was hand-laid and finished. The RC30 bristles with little touches that show the extent of the thinking behind it, such as the small crease in one of the exhaust pipes to clear the rear chain, this necessitating a very slight difference in jetting for the respective cylinder.

For 1987, a batch of 1,000 RC30s was built for the home market, but these were severely detuned, producing just 77 hp, with small diameter headlights and black mirrors. This production completed the required homologation for the 1988 Superbike World Championship. When the RC30 went on sale in the UK in 1988, it was listed at a staggering £8,495, while Honda asked, and received, $14,000 for the 90 examples that were originally earmarked for the Australian market. It is believed that this number subsequently increased to 145, all delivered in 1988.

For racing, HRC produced a kit comprising an exhaust system, radiator, transmission set, different gearing, handlebars, steering damper, front and rear race wheels, special brake calipers, axles and carburettor jets.

The White Ghost

Myths and legends gather with the passage of time, and one such surrounds the Honda RC30. Prior to the release of the model itself, Honda constructed around thirty examples, finished in stark Ross White, some of which were supplied to Travelling Marshals at the 1987 Suzuka Eight Hour Race – an event of paramount important to the Japanese manufacturers, and one that draws a massive live crowd and television audience. These bikes, which have become known as White Ghosts, were built to demonstrate only, albeit at speeds to keep up with the race field, and were supposedly in a lower degree of specification and tune to what became the customer and race models. However just how many of them made it onto the track at Suzuka is unclear, and some are believed to have been given to HRC customers around the world for promotional purposes.

The RC30: A collectors’ item

Unsurprisingly, there is now a healthy world-wide trade in RC30s, but it’s worth knowing what to look for and how to identify the various models. The original JDM (Japanese Domestic Market) models are very detuned with modified ignition, carburettors, exhausts and rev-limitation, and can be complicated to beef up to Australian specification, although it can be done. Bikes that have been laid up for some time tend to develop fuel leaks which are caused by the hardening of the many tiny rubber O-rings in the carburettors and fuel system. This means fuel dribbles over the engine and settles in the belly of the fairing – a rather unsatisfactory situation.

Australia/Europe models are distinguished by the VFR750R designation on both sides of the seat cowling. British models have larger diameter headlights and mirrors are finished in white. In 1990, the US market received models with about 86hp on tap for the 49-state model (which features a “0” in the 8th position of the VIN). The California-only model (which is identified by a “1” in the 8th position of the VIN) was even more restricted and had a low lift cam and softer valve springs and a 12,000 rpm red line, while the rest of the US models ran to 12,500 rpm. The U.S. version is also distinguished by the “RC30” decal on the tail. There was also a handful of RC30s produced for the UK market in 1990, the model enjoying phenomenal popularity in the light of the continuing successes at the Isle of Man TT.

Of course, many, perhaps the majority of RC30s were raced, and some converted back to road spec once their track days were over. Warped front discs are fairly common where bikes have been subjected to competition. The fairing appears to contain two slightly different shades of red, and many collectors make the mistake of having this repainted to match the colour in the lower section. However the truth of the matter is that the top section is actually a decal, and was used by Honda to guard against having paint chipped by the three Dzus fasteners.

Just Like Joey’s

To ride a Honda RC30 is about as rare as meeting Michael Jordan; to spend a few weeks as the custodian of such a machine, even more so. That’s what happened when American Honda arranged for me to have a few weeks on this stunning 1990 edition, resplendent in a Joey Dunlop colour scheme that is so close to the colours he raced you’d be very hard to find a flaw. The RC30 is owned by a gentleman in Southern California, a Honda enthusiast who is clearly more trusting than I am, but I wasn’t about to say “no” to a few rides on perhaps the greatest production street bike Honda ever created.

The RC30 was stock aside from the race exhaust and different jetting to suit, although details are rather sketchy. It sure feels like it has more than the 85-ish horsepower the California models came out with, and is jetted so beautifully it feels like the throttle is almost an extension of my muscle memory.

The procedure from cold is to engage the choke poking out from the left side of the fairing, thumb the starter and let the engine warm up at a constant, high idle. This is important as the clearances within the engine are extremely fine, and cold seizures are not unknown.

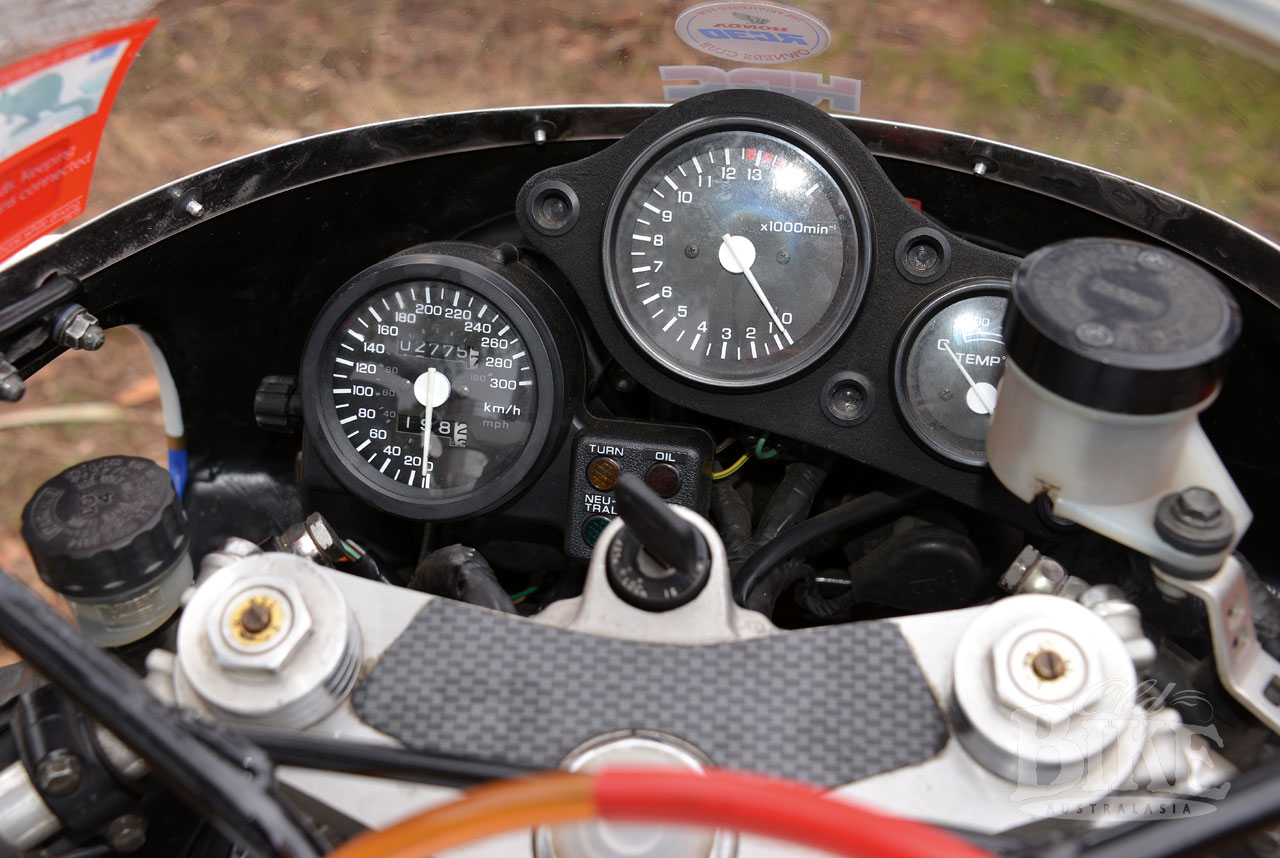

It’s how some things really were better back in the day. Compared to a modern bike, one that has to comply with untold emissions regulations that ruin a nice throttle response, the RC30’s initial delivery of the power is velvety smooth. Power is delivered so seamlessly and to a chassis so compliant, you start building up speed far faster than you’d think for a 30-year-old motorcycle. First gear is exceedingly tall, with second-third-fourth gears very close together before spacing out again for fifth and sixth. Yet the gearbox is so light and direct, it’s right up there with the best gearboxes I’ve ever used—new or old. Remember, there’s no electronics working here. Just refined mechanical excellence in operation.

Overall, the RC30 is tiny. It’s not much bigger than the VFR400 that came out at the same time, and for a rider of my 185cm frame, I’m about half a foot too tall for it. But the RC still flatters a relative giant like me in how clearly it communicated with the rider, telling me exactly where the wheels are, what’s happening with the suspension… all while accompanied by one of the greatest mechanical sound tracks ever created.

The svelte chassis simply decimates corners. With a weight bias heavily leaned towards the front and that 18-inch rear wheel matched to the 17-inch front, you can easily fall into the trap of taking multiple stabs at a corner, such is the sheer turn speed if the chassis. You can change lines on a whim—the RC30 will simply abide by your thoughts almost before they become actions. It’s not 250cc Grand Prix levels of agility, but for a four-stroke, it’s one of the very finest I’ve ridden when it comes to letting the rider pick and choose lines at any point while riding. The brakes serve to show just how far we’ve come in the last 30 years. While good in that the feel is there, an RC30 simply misses the overall power we’ve all become used to with regards to braking systems. However, that fact reminds you to take it a bit easy, as damaging one of these beauties simply isn’t worth thinking about.

The RC30 is not a bike to go and get lunch on. It’s a thoroughbred racer, born from within the walls of HRC. You know this because if you sit at the lights for any great length of time, the temperature gauge will rise almost as fast as the revs. The rear cylinder becomes extremely hot, so you need to make sure you have fresh air, devoid of cars in front, to keep the temp gauge under control.

Regardless of this, the RC30 is an utterly incredible machine. It’s always nice when you meet a hero and they are as cool as you’d hoped, and the RC frankly surpassed my expectation. The RC steers better than most modern bikes and has a presence they could only dream of, and I’m honoured Jon Sidel and the crew at American Honda organized this test for me.

*Thanks also to Sam Bateman for supplying his RC30 for some of the Australian photographs included here.

Specifications: Honda VFR750R/RC30 (Australia/Europe model)

Period of production: 1987-1990.

Engine: 90º v-four, liquid cooled. Double overhead camshafts, gear-driven.

Bore x stroke: 70.0mm x 48.6mm = 748cc.

Gearbox: Six speed, chain rear drive

Compression ratio: 11.0:1

Carburation: Four 38mm Keihin CV

Power: 112 hp @ 12,500 rpm

Chassis: Aluminium twin-spar, single-sided aluminium swinging arm.

Front forks: Showa 43 mm cartridge type.

Brakes: Front: Twin 310 mm discs with Nissin four-piston calipers

Rear: Single disc with twin-piston caliper.

Fuel capacity: 18 litres

Weight: 185kg

Wheelbase: 1407mm

Wheels/tyres: Cast magnesium alloy.

Front: 120/70-17, 3.00-inch rim

Rear: 170/60-18, 5.5-inch rim.

Top speed: 254 km/h.