Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: John Fretten, Jim Scaysbrook, Rob Lewis

From virtually owning the big bike market from 1969 to 1972, Honda steadily divested itself of the crown as the ‘seventies rolled by. Initially under fire from the Kawasaki Z1, further erosion came in the form of the Suzuki GT750 and the all-new GS750 as well as revised 900 and 1000cc versions of the Kawasaki four. When Yamaha’s XS1100 joined the ranks, Honda’s 750 was looking very ancient indeed. Honda meekly countered with the CB750F1 of 1977; a face-lifted version of the long serving SOHC two-valve four, but by and large it was received with yawns rather than yelps of delight. Clearly, it was time to bury the king and confront the enemy with a new weapon and marketing strategy.

That strategy, in order to not just remain competitive but to give the media something to talk about, needed to encompass the rapidly emerging technology that characterized the latter stages of the air-cooled era. Four valve heads were nothing new to Honda; in fact their successful racers had employed this feature for two decades. It wasn’t so much the technology, but producing it at an affordable price – so vital in a price-driven market like this one.

Slide back to December 1977, when a handful of trusted journalists were invited to Japan by the Honda Motor Company to witness the unveiling of the company’s most adventurous production motorcycle yet – the six cylinder CBX1000. The jaw-dropping power plant had been designed by Soichiro Irimajiri – the man responsible for the all-conquering works 250cc and 297cc six cylinder racers, as well as the 23,000 rpm 50cc twin and the five-cylinder 125. Yet for all the headline grabbing achieved by the CBX, it was anything but a runaway best seller. The buying public perceived it as big and cumbersome, and expensive. And while the CBX is a story in itself, the six was in fact just the first of the new generation from Honda that would soon include an all-new 750 and then a 900.

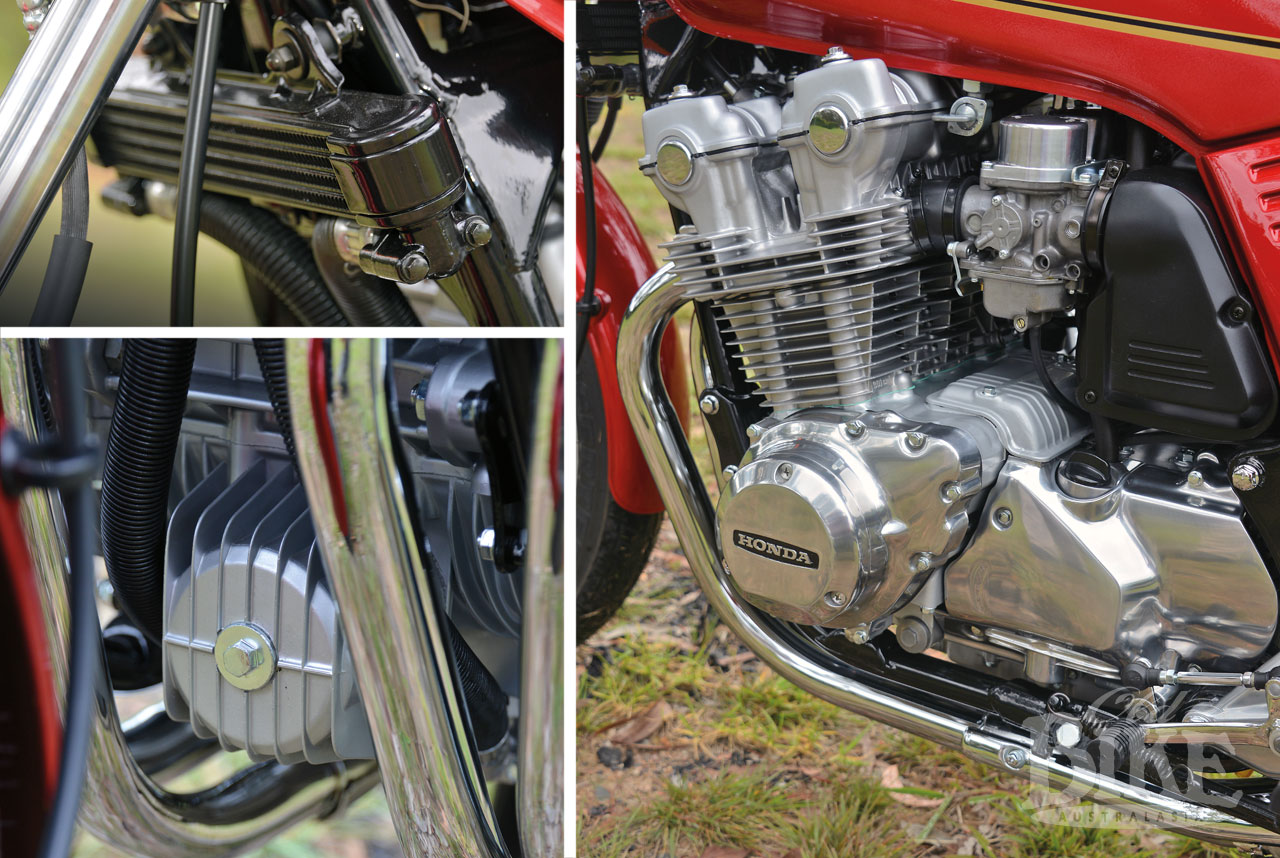

The cylinder head of all three models shared the new four-valve combustion chamber (actually not that new, having been introduced on the XL250 single as far back as 1971) with centrally positioned spark plug and a Hy-Vo chain running up the centre of the engine to the exhaust camshaft, with a second chain from the exhaust cam driving the inlet camshaft. However in the CBX and both the new fours, gone were conventional rocker arm, with valves operated by buckets and shims bearing directly on the camshaft. Downstairs, the alternator sat on the right side of the crankshaft with the CDI ignition on the left. The basis for this engine – in four cylinder form – had been well proven in the Honda RCB Endurance racers. Designed for the FIM Coupe d’Europe Endurance series, these engines used the original CB750 dry sump bottom end and at first displaced 915cc, then 941cc, 997cc and finally 998cc, with four valves per cylinder and double, gear-driven overhead camshafts. They also used Honda’s Comstar wheels which had the hubs and rims joined by a pair of five-spoke pressings, riveted together.

The first of the new DOHC fours seen Down Under was the CB750K, or KZ, which had similar styling to the CBX, but with four separate exhaust pipes finishing in megaphone style silencers. However there was an all-new styling trend about to be unleashed; an angular design which blended the tank, side covers and rear seat base into an integrated unit. This was carried through the range from the CB250N up to the CB900.

The CBX had been on sale for around a year by the time Honda released the CB750F and (in Europe and not the USA), the CB900F. The 900 shared the same 64.5mm bore with the CBX, while the 750 was square at 62mm x 62mm. Externally, the 750 and 900 were almost identical, save for the standard oil cooler on the larger model. Something else the fours shared were fairly average forks and brakes, and a swinging arm running in nylon bushes that quickly developed play at the pivot and did nothing for the overall handling. To Honda’s credit, both these issues were fairly quickly addressed. For the 1980 model year, the frame received needle roller bearings (as on the Suzuki GS models) and the forks were beefed up. The frame of the CB900 was quite conventional, with the right side bottom frame rail bolted up and easily removable to allow the engine to be easily taken out of the frame. The front brakes were also quite unremarkable, given the rapid development in this area at the time. The calipers used a single, fixed inner pad with a single floating outer pad, clamping onto 276mm stainless discs.

Honda’s Comstar pressed aluminium wheels graced all models, and drew justified criticism for their lateral flexing and inability for the rims to withstand decent jolts. Even in the simple process of changing tyres, the wheels could distort unless treated with extreme care. Honda’s subsequent answer was to reverse the components that made up the wheel – turning the ‘spoke’ sections outwards for greater torsional rigidity. It seemed to do the trick and looked better too.

Of the three new-generation multis, the middleweight of the trio, the CB900F, or Bol D’or as it was also known in Europe and Australia, became the favourite, with its broader spread of torque and higher power output over the 750. Unlike the 750, which needed around 5,500 on the tacho before it began to operate, the 900 would pull strongly from as little as 3,000 rpm. It sold so well in Europe that the Americans were soon clamoring for the model to be released in the States, but it took until 1981 for Honda to acquiesce.

The original model 900, the CB900FZ, had conventional forks that were not adjustable for either spring pre-load or dampening. In 1980, the second iteration appeared as the CB900FA, with individual air caps on each fork leg, and ‘reversed’ Comstar wheels. On the subsequent CB900FB, fork tube diameter increased from 35mm to 37mm and the air fork caps were linked by a rubber tube, and a second –much heavier – model, the CB900F2B, featured a half fairing with leg shields similar to the final version of the CBX1000. Produced from February 1982 to February 1983, the CB900FC and F2C sported a new version of the Comstar wheel which used three crescent shaped ‘spoke’ pressings on each side. Fork diameter was up to 39mm and Honda’s new TRAC dual piston brakes, which used a form of anti-dive, appeared. The following year’s FD and F2D models were basically identical except for black-chroming on the exhaust system.

When the CB900 finally made it to USA for 1981, it featured a rubber-mounted engine, 39mm air-assisted front forks, and a wider rear rim on the Comstar wheel. The latter was a criticism that lasted throughout the non-US CB900’s production – the narrowness of the rear rim severely restricting the use of new generation tyres.

An eye on the track

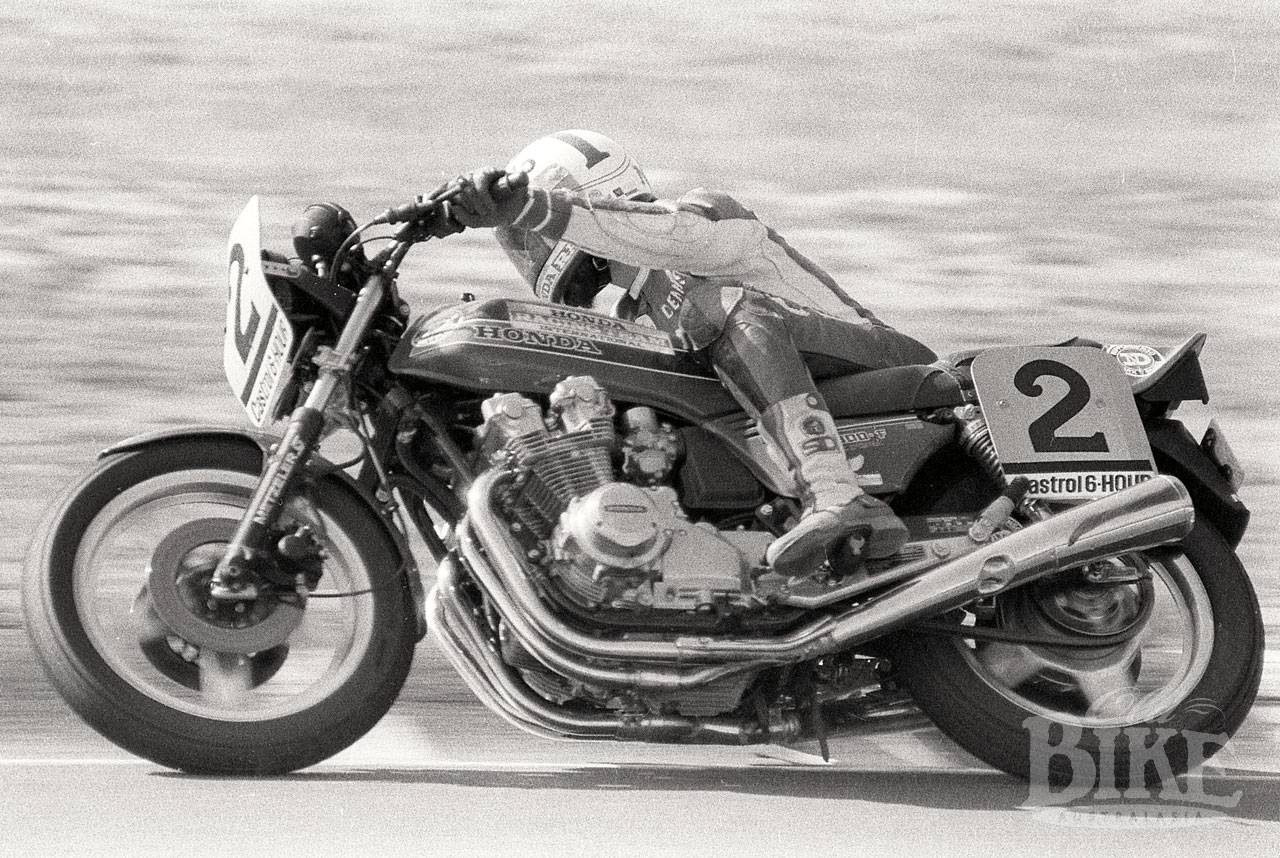

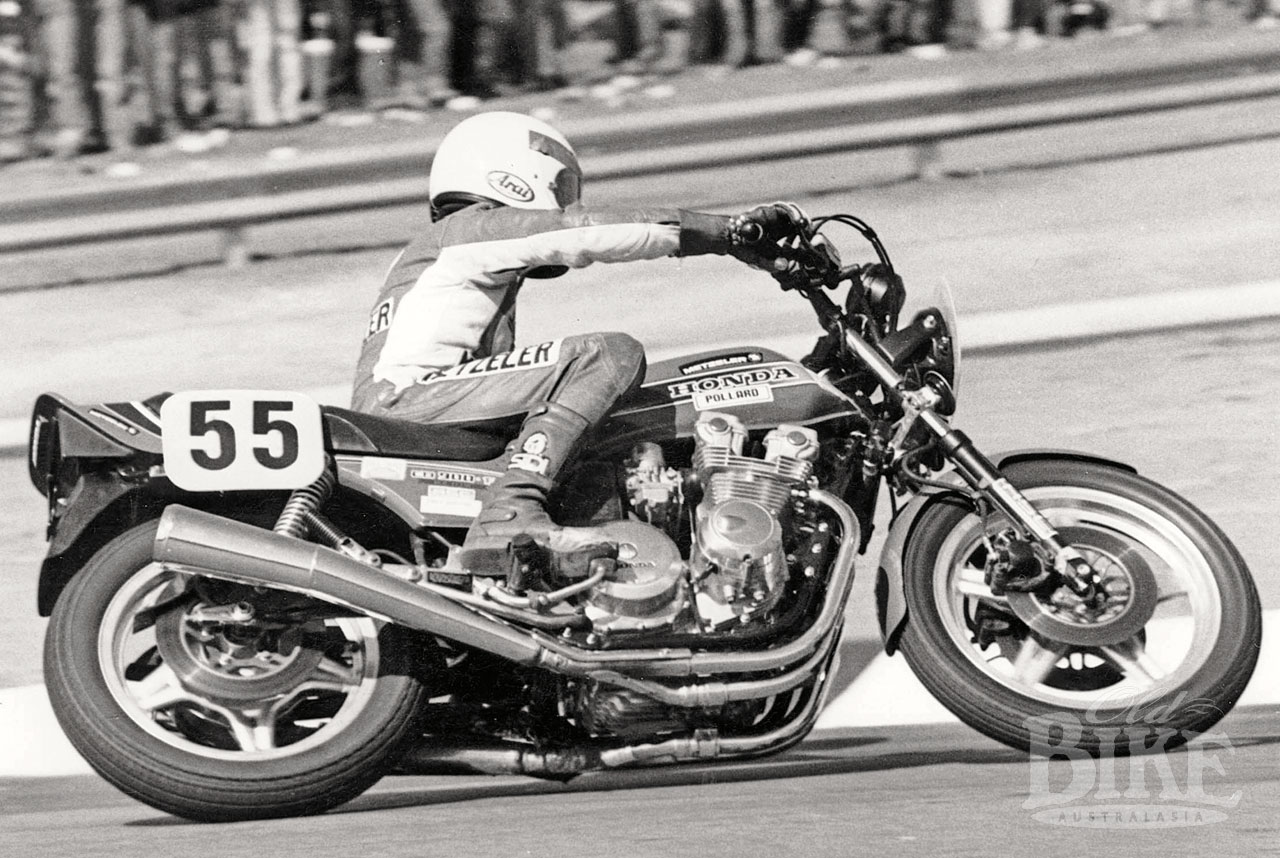

When the CB900 hit Australasia, it was immediately snapped up by the Production Racing set, and was ready in time for the 1979 Australian Grand Prix meeting at Bathurst. The Unlimited Production Race was set to be a memorable encounter between the new Suzuki GS1000, the gargantuan six cylinder Kawasaki 1300, and the CB900, and the race itself turned out to be a classic. As Garry Thomas slid and bounced the big Kawasaki around, Tony Hatton stayed tucked in behind on the CB900, benefitting from the considerable slipstream created by the 1300. On the final lap, Hatton pushed his way past over the mountain and with a particularly spirited run down the Esses, managed to create a sufficient gap to hold the advantage to the chequered flag.

Six months later came the all-important Castrol Six Hour Race at Amaroo Park, and no fewer than ten CB900s were entered. In practice, Hatton’s machine broke a conrod (not an entirely uncommon occurrence with these engines when pushed hard), throwing him off heavily. Hatton’s broken fingers forced him out, and with a fresh CB900 procured, John Warrian was drafted in to ride with Ken Blake. In qualifying, Dennis Neill took his CB900 around in 57.7 seconds to secure pole position, but his chances of a race win evaporated when he tangled with Ron Boulden early in the race.

But it wasn’t just Production Racing where the new 900 was being eyed. Several notable tuners, among them Peter Molloy who had an enviable reputation as an engine builder in the car side of the sport, used the new model as a basis for serious runners in the Superbike category, which was now included in the Australian Unlimited Road Racing Championship, previously the domain of the TZ750 Yamaha two-strokes. Sydney dealership Mentor Motorcycles engaged Molloy to build a CB900-based racer for young charger Wayne Gardner to ride in selected rounds of the 1980 championship. The series reached its conclusion at Melbourne’s Sandown Park, and in difficult conditions, Gardner scored the first four-stroke win in a ARRC race – an achievement which did not go unnoticed by Honda executives in the pits.

A resurrection

Former Honda dealer John Fretten always had a soft spot for the CB900. As well as Production Racing the similar CB750F, he built himself a CB900-based Superbike using many Honda RSC parts. “I loved that bike,” he says. “It was quick, reliable, and handled beautifully. What more could you want?” He also recalls that the standard models, of which he sold plenty through his dealership at Blacktown in Sydney’s western suburbs, were not without their shortcomings. “The first model had fairly ordinary suspension and the brakes weren’t much better. The rear end wasn’t so bad, but with so many possible spring and damping settings for the rear shocks, it was hard to know what actually worked best. On the other hand, there was no adjustment on the front until they brought out the air caps on the second model. They never really fixed the brakes until they went to the twin-piston calipers later, which were the same as on the CB1100F and were quite good. The motors could give trouble too, particularly if they were ridden hard. Cam chains were prone to wearing out, and they even broke rods occasionally. But overall, the 900 was an amazing bike and very quick. They’d do a genuine 130 mph at places like Bathurst.”

Since his retirement from the motorcycle trade, John has surrounded himself with all sorts of ‘projects’, several of which have been featured in OBA. Along the way, he ended up with a very tired old CB900FB which had been hand-painted black. “It just sat in my shed while I did up all these other bikes, and I really had no intention of restoring it. But when I’d finished all the others (‘the others’ include a TX750 Yamaha, RC30 Honda, VF1000R Honda and a Suzuki RE5) I thought I would give the 900 a bit of a birthday.”

John’s work is fastidious and with absolutely no compromises as to quality or originality. The bike is the second model, fitted with the reversed Comstar wheels and the individual air caps for the forks. Vitally, he managed to find an original exhaust system – one of the hardest items to source when restoring any of the Honda ‘fours’ of this era – although there are now after-market replica systems available in Australia. The deep, lustrous chrome plating was done by Swift Electroplating in Silverwater, Sydney, and the paintwork by now-retired Ron Keed who also created the decals for the fuel tank and side covers.

Starting involves the simple procedure of thumbing the choke lever mounted on the top of the left side handlebar switch and letting the engine warm up until it settles into a regular rhythm. With all the chains inside there’s a fair amount of rumbling and the clutch does have its own piece of music happening when not engaged, but overall the sound is purposeful, accentuated by the deep purr coming from the twin mufflers.

My own experience

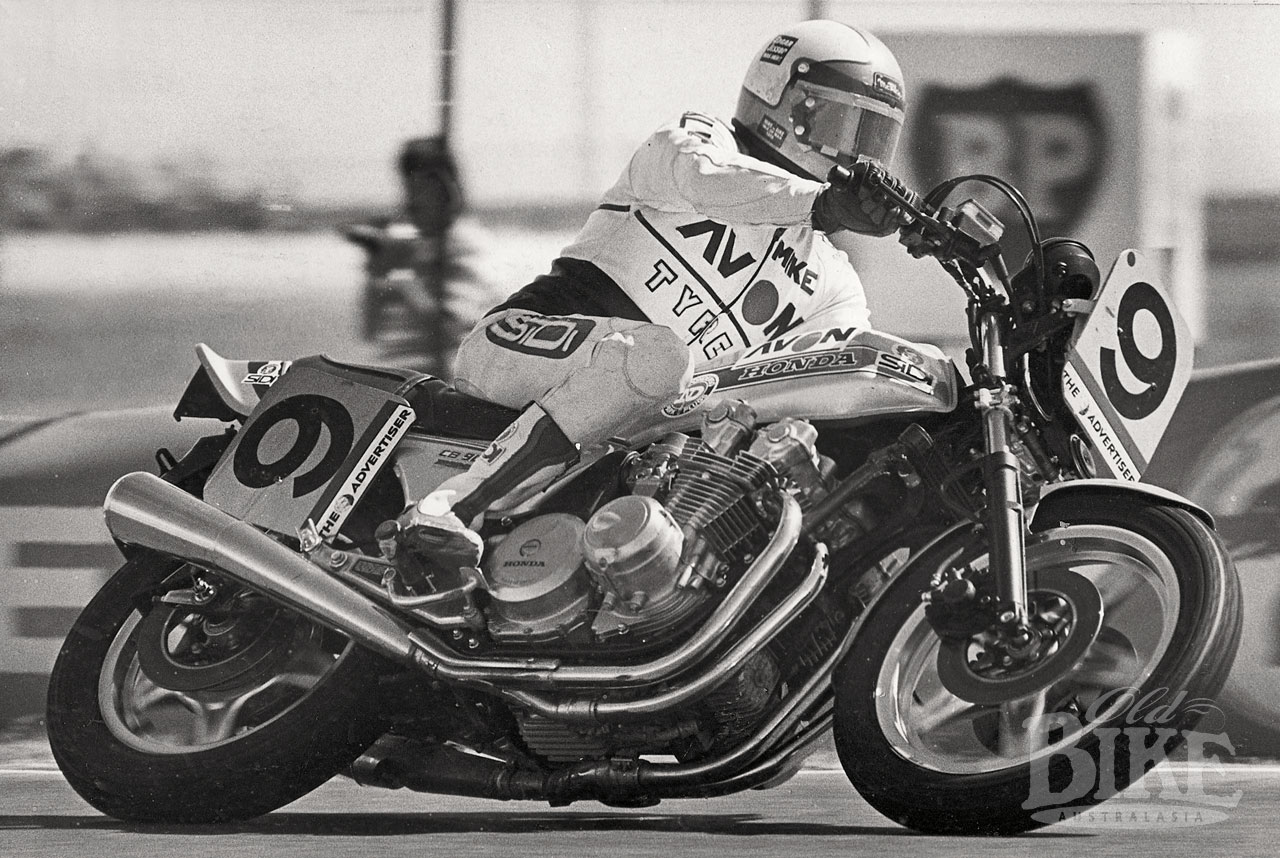

If John has a soft spot for the 900, so have I, having owned two in my time – a first model silver CB900F and a third model black CB900FB. The original bike I bought primarily to race with Mike Hailwood in the 1979 Adelaide Three Hour, where we managed to run out of petrol not once but twice. We also had a third unscheduled stop after being black-flagged for a loose number plate – bugger! Even worse, both Mike and I had trouble keeping the alternator cover off the deck on the right handers, with the result that it stopped charging and the bike ground to a halt with a flat battery just after we had taken the chequered flag.

A few weeks later at Bathurst I experienced some serious problems with the Avon Roadrunner tyres in practice and switched to Pirellis for the Arai Three Hour Race on Easter Saturday. This was a decision taken with only minutes to spare and unfortunately the Pirelli tyre fitter managed to buckle the Comstar front wheel in the process – something I quickly discovered on the opening lap of the race. Instead of a Three Hour Race, it became a three-minute race for me.

The silver CB900 became my ride-to-work bike thereafter and I loved everything about it except the front brakes. This was not merely a lack of braking performance; the calipers would grind and squawk incessantly until it was finally discovered that the mounting lugs on the fork sliders had been machined incorrectly from the factory – I could hardly believe Honda was capable of such a thing. It was Honda dealer Ric Andrews who discovered the fault, but rather than attempt to fix it, he convinced me to trade it in on a new CB900FB. Rick always was a super salesman. Although I never raced the second 900, it was a lovely machine, and even had half-decent brakes!

Specifications: 1980 Honda CB900FA

Engine: Four cylinder air cooled DOHC four-valves per cylinder. Chain driven camshafts. Five plain main bearings with plain big end bearings. Wet sump.

Bore x stroke: 64.5mm x 69mm 902cc

Carburettors: Four 32mm Keihin CV.

Power: 95hp at 9,000 rpm.

Torque: 77 Nm at 8,000 rpm

Transmission: Five speed gearbox with chain final drive.

Electrical: CDI ignition, 12v 260 watt alternator, electric starter

Suspension: Telescopic front fork with air adjustment. Showa FVQ shock absorbers with four-way damping adjustment and five position spring preload.

Brakes: 2 x 276 mm front discs , single 297mm rear disc.

Wheels: Front; 2.15 x 19 rim with 3.25 x 19 tyre. Rear; 3.25 x 19 rim with 4.00 x 18 tyre.

Wheelbase: 1536mm

Dry weight: 244kg

Fuel capacity: 20 litres

Top speed: 129 mph (207 km/h)