They breed ‘em tough in the bush. Harry Pyne was a classic example of a man who never walked away from a challenge.

Tamworth is today a thriving city of around 55,000 people. It grew from the pioneering efforts of the Australian Agricultural Company, which established the sheep and cattle industry in the area in the 1830s. The settlement that grew up around the Peel River (named after Sir Robert Peel, twice Prime Minister of Great Britain) became known as Tamworth, as the Peel family had a long association with the town of that name in the English Midlands. The early days were tough. The only regular track connecting Tamworth with the coast led through the bush across the Liverpool Range and the Hunter Valley, and could be cut off for months by floods or drought (resulting in lack of feed for draught animals). The traditional inhabitants of the area also did not take kindly to the new arrivals. When gold was discovered at nearby Nundle in 1851, people flooded into the area. The rail line from Newcastle reached Tamworth in 1878, and in 1888 Tamworth became the first town in the Southern Hemisphere to have its streets lit by a Council-owned generating plant, earning it the nickname, “City of Light”. From there on the town grew exponentially, to the point that in the 1920s, a very strong lobby (the New England State Movement) pushed for the area to become a state separate from New South Wales. Today, the district is home to the enormously successful County Music Festival (and Moto GP star Casey Stoner), but in the past it was also a motorcycle sport centre, thanks in no small way to the enthusiasm and energy of Harry Pyne.

Born in 1922, Harry displayed an early talent for music and art and at the age of 12 was playing in a brass band. He was also a keen artist and earned pocket money doing signwork and illustrations. At 14 he won a scholarship to study with the famous bird artist Nevil Cayley. He left school at the same time, right in the middle of the Great Depression, but had no trouble finding employment as a ticket writer, window dresser and salesman with Fossey’s Chain Stores, earning 17 shillings and 6 pence per week. He was busily painting the inside of a window depicting a back-to-school display, when a man standing outside beckoned to him. It was Arthur Sarroff, who owned a rival chain store, and he offered young Harry thirty bob a week to work for him, with the additional incentive to train him to be the best salesman in town. He took the job and after his window dressing and ticket writing duties, would go onto the sales floor on Friday nights and Saturdays. As soon as he gained his driving licence at 16 he was given a Ford A panel van, and with a 14-year-old junior salesman as passenger and the van loaded with clothing and other goods, packed off onto the road and told not to come back until everything was sold. It took him just four days to flog the lot and collect a five pounds commission. Despite the financial rewards, the gypsy-like existence on the road didn’t suit Harry, and he moved to Newcastle to take up a sales post with the Cooee Clothing Company. The tyrannical boss, Lionel Israel, kept a beady eye on the entire sales floor from his office and if somebody walked out without buying anything, the sales person responsible was called to his office to explain why. The sales target was £300 per week for a senior and £100 for a junior. If you failed to reach your target you were out the door.

Prior to this, Harry had bought a 1928 side valve BSA, paying off the £25 price over six months and gazing longingly at the machine in the shop until he was able to make the final payment and take possession. The proprietor told Harry to ‘put the bike in second gear and leave it there’, which he did. Arriving home with his purchase, his parents were furious and demanded he get rid of it or be kicked out. His spirit must have prevailed, because he kept the BSA and obtained his licence. After the experience with Cooee, Harry made the decision to go out on his own as a signwriter, but then along came the war. Although he requested to be put in the motorcycle corps, he was trade listed as signwriter and musician, so he spent the next four years playing in brass bands and painting signs, back drops and scenes for musical plays, as well as doing military PR work.

After his discharge, he began doing contract signwriting and advertising work for tobacco company W.D. & H.O. Wills, based in Tamworth, but travelling between Newcastle and the Queensland border. On his travels, he bought as many motorcycles as he could find and quickly built up a very profitable sideline dispensing the bikes to a hungry market back home.

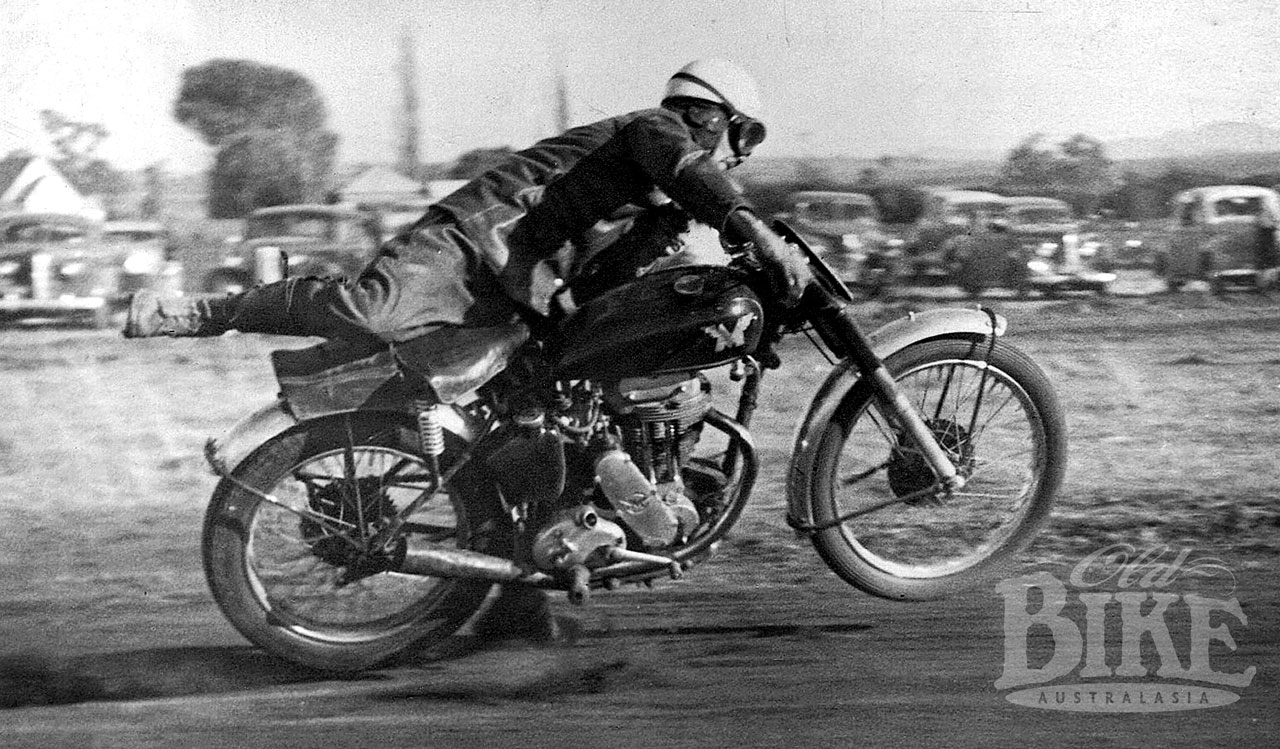

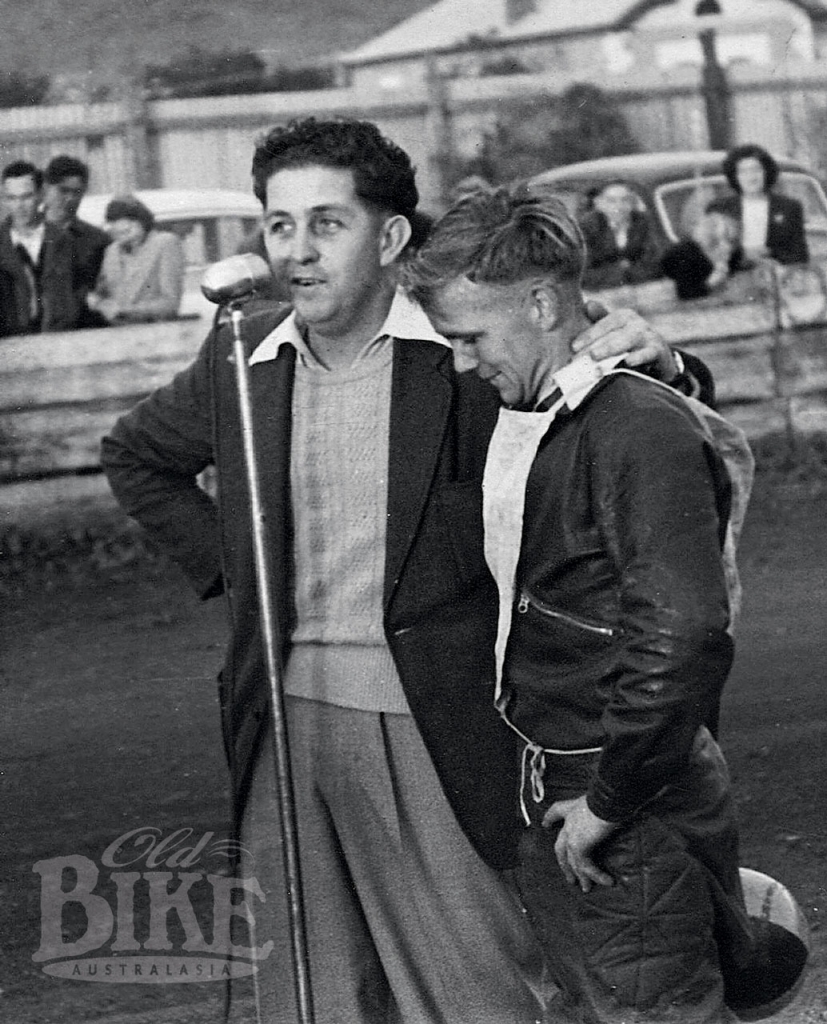

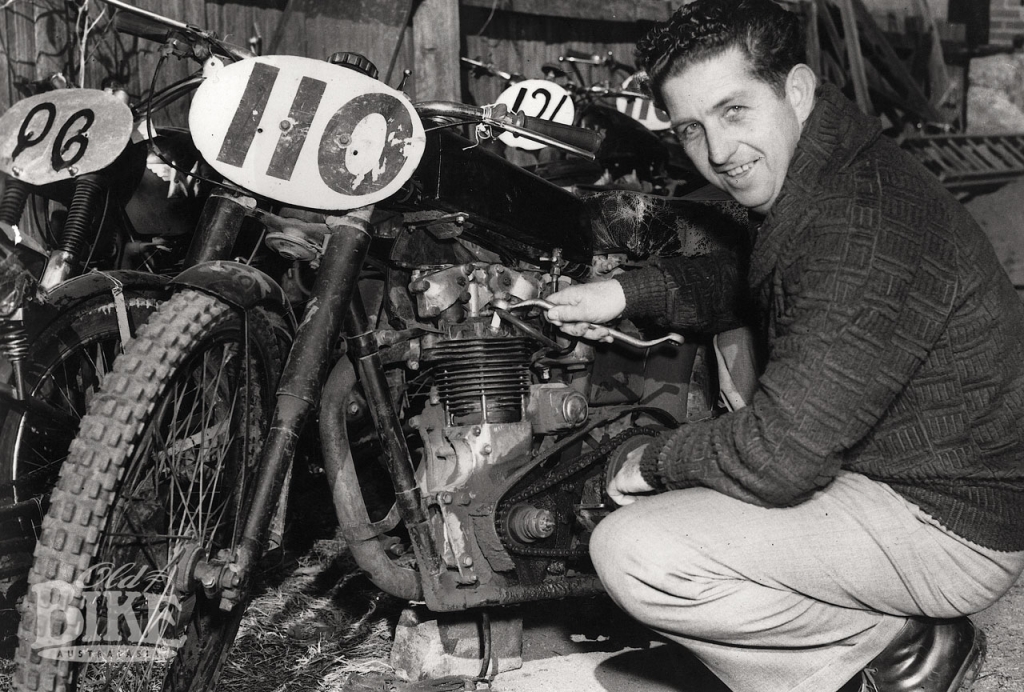

1946 was a big year for Harry. With agencies for AJS and Velocette, he opened his own motorcycle shop, and also formed the Tamworth Motorcycle Club. In typically dynamic fashion, he organised the club’s activities, prepared the programmes, ran the races, rode in virtually every race and was rarely beaten in the club championships. In 1972 he became the club’s first life member. Naturally he was instrumental in promoting tracks in the district, such as the Nemingah Short Circuit and the one mile ‘Mountain’ scrambles track on the banks of the Peel River, which was more of a high speed dirt track than the usual rough and tumble circuits like Moorebank in Sydney. In 1957 the NSW Scrambles Championships were allocated to the track, attracting entries from reigning Australian champion Peter Nicol from WA, Victorian Champion George Bailey, and Gerry Vial and Blair Harley, who had just returned from racing in Europe. But the visitors had plenty of opposition in the home star; Harry winning the 250 cc Lightweight and lapping everyone except Nicol to win the 350 cc Junior. In the premier Senior title, Nicol and Harry rode wheel to wheel for the entire 20 lap distance, the WA star getting the verdict by less than a metre.

The year before, Harry acquired one of the very few factory Velocette scramblers to reach Australia. In reality, the Scrambler, which was also offered as an Endurance model in the USA, varied little in technical specification from the MSS road bike, apart from a wide-ratio gearbox, two-way damped front forks, higher compression and different cams. Light alloy mudguards, a smaller seat and a 2.5 gallon petrol tank were fitted for an all-up weight of 335 pounds (152 kg). Although the Velos were theoretically no match for the likes of Nicol’s Gold Star BSA, nobody told Harry that and the Senior race that day was talked about for years to come. The 500 Velocette Scrambler is today in the collection of Motorcycling Australia in Melbourne.

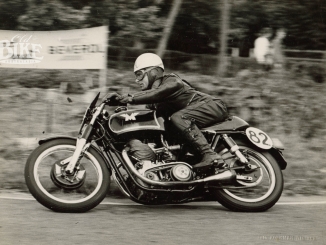

Although he tended to concentrate on racing in his home district, Harry also made regular trips to Moorebank in Sydney where he always acquitted himself well, (he won the first-ever race at the opening meeting of the track, the Lightweight in November 1953) and he also dabbled in road racing, competing at Bathurst several times and also at Gnoo Blas in Orange. Younger brother George was also a dab hand on a dirt bike, and later occupied senior positions with Honda and Yamaha. George also played a big role in assisting young talent with decent machinery, Tony Hatton and this writer to name just two. George supplied me with a number of bikes including his own heavily worked-over Honda SL125 and the first CR250 Elsinore in Australia. During the 1970s, I regularly raced at the Nemingah Short Circuit and also at Harry’s own track, staying with Harry and his wife Dulcie at their spacious home overlooking the track. Harry always insisted a good breakfast was important for top performance, and on race day I was always served a gigantic T-bone steak for the first meal of the day. I didn’t need any lunch!

With the imminent threat of the closure of the Nemingah track, situated on the northern side of town behind a quaint little church (racing could never start on Sunday until the church service concluded) Harry but his own racing complex which he called Pyne Park on his property on the Sydney Road. The complex was progressively developed to include a Short Circuit, Moto Cross, Speedway and Flat Track.

While the motorcycle business continued to do well, Harry could see the writing on the wall as the ‘50s drew to a close. By 1962 he had sold his last English bike and became the first Honda dealer in Tamworth, also holding the original franchises for Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki in the district. He told Lloyd Williams, who interviewed him for the Motorcycle Industry Magazine in 1985, “To understand the Japanese way of life and doing business as compared to the old English bike scene required a complete rethink. I enjoyed the early years of my business, being pro-English. Being low-volume production bikes the ease of maintenance was good and the availability of spare never a problem, it was easy to provide a good back-up service that is really important to any business. With the easy post-war years way of doing business it was more difficult getting new bikes than selling them. The reps would call on you and most of the business was done in the pub. It was a great social scene and most sales were made being a good bloke and getting the bikes. Going to work was simply fun and games, particularly when your whole life revolved around motorcycles and mutual trust and respect.

Running parallel to his motorcycle interest for many years, Harry built up a successful Rootes Group (Sunbeam, Hillman, Humber and Talbot) dealership in Tamworth, but when Chrysler took over the collapsed British company they demanded he stop selling motorcycles. His reply was to tell them to jump in the lake, and changed to the fledgling Toyota marque. For 17 years Harry was one of Toyota’s leading country dealers, winning many sales competitions and trips to Japan, but the company later required their dealers to stock both trucks and cars, and Harry wasn’t interested in trucks. He relinquished the business and remained with his first love, motorcycles.

Selling the Japanese motorcycle brands was a far cry from the old days of doing business in the pub, especially with the huge spare parts inventory needed to service the ever-expanding range of models. By the late 1980s Harry had been in business for over 40 years and pulled the dealership back to concentrate on Yamaha, which he did very effectively. Eventually the business was sold but continued as a Yamaha dealer to the present time, while Harry was forced to take things a little easier due to his advancing years. For almost half a century, he had worked six days a week in his business, and spent the other day engaged in some sort of motor cycling activity. Harry was under no illusion as to the secret of his success, “ You have got to have a personality, an innate sense of cunning, an ability to evaluate situations quickly and you’ve got to know when to apologise for someone’s mistake and know when to throw someone off the premises for not trying to communicate.”

Harry Pyne died on February 8th, 2002, aged 79. In terms of motorcycle sport and as an enthusiastic and highly successful entrepreneur in various motoring fields, he put Tamworth on the map and his name is still very much associated with the district.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook with grateful acknowledgement to Lloyd Williams