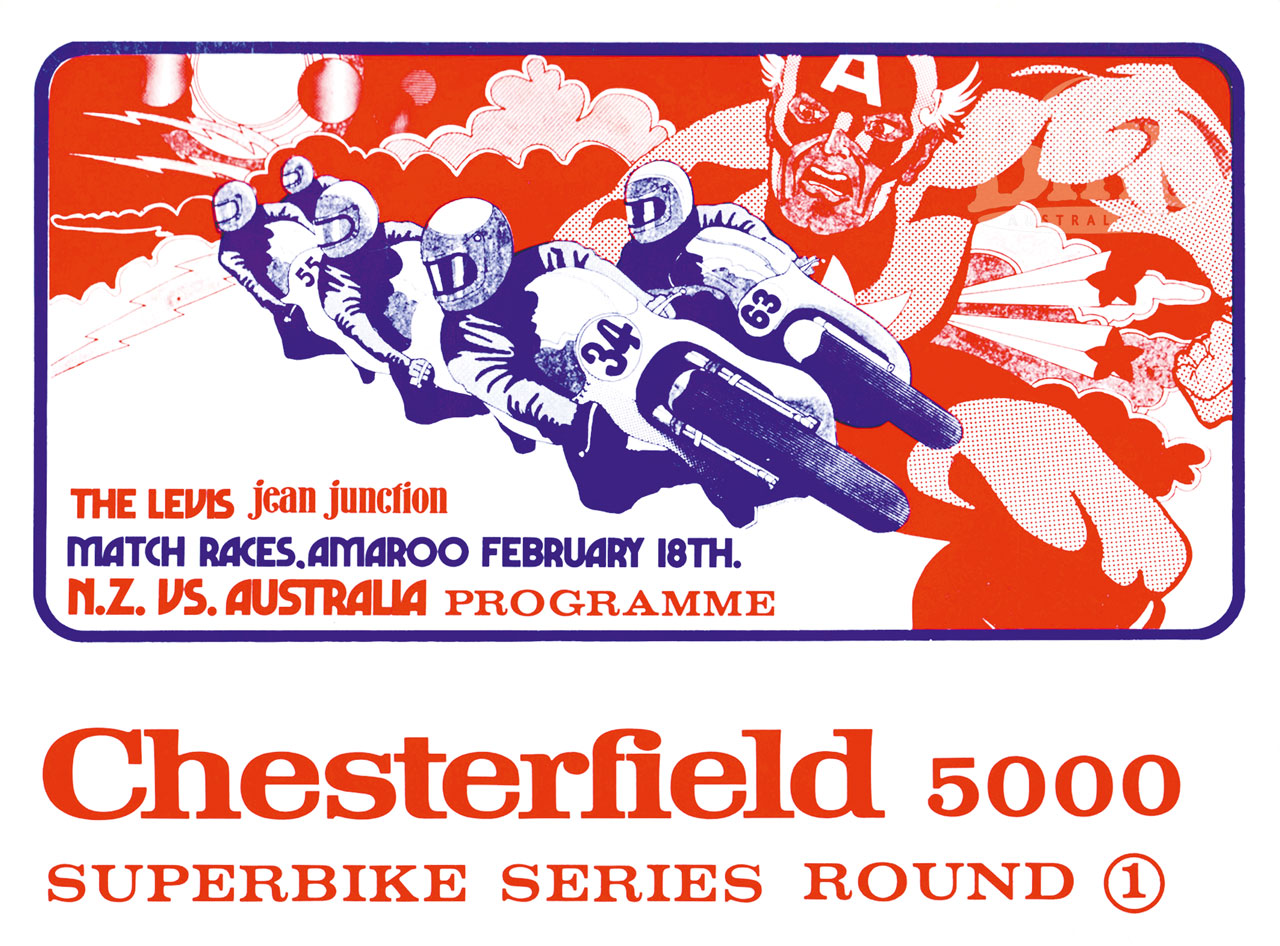

These days, the term Superbike has slipped into the language as a definitive term just like Biro or Hoover. It proliferated in Europe and particularly America in the mid 1970s, but make no mistake, Superbike racing began right here in Australia, at Amaroo Park on 18 February, 1973 to be precise.

The little Sydney circuit was at the time,the hotbed of road racing in the state, thanks to energetic promotion by the Willoughby District Motor Cycle Club, and its organising secretary Vincent Tesoriero. The club had broken the traditional road racing mould by adopting various sprint races as opposed to the usual capacity categories with 8 or ten lap races, but the concept that was drafted prior to the start of the 1973 season was radical in the extreme.

Tesoriero recalls the lead-up to the announcement of the series. “One of the real characters around at the time was the artist Peter Ledger, who was a larger than life character in every sense of the expression. Ledger was a boisterous, sometimes annoying extrovert who dressed in outrageous gear, including Lederhosen and leather chaps, and who was totally gone on science fiction animation and character drawings. He did a lot of work for super-hero type comic books, and he lived the part as well. I wanted to break away from the same old designs for road racing posters and programmes that had been around for decades, and I had this idea for a series that probably had more to do with speedway than road racing. One of the key factors was that Chesterfield was dead keen to get involved, and they were very receptive to some fresh thinking.”

In this period, tobacco advertising was not just tolerated, but courted by every sporting promoter in the country. Motor sport, with its macho image, was particularly targeted by the gasper floggers, and the Chesterfield brand had personal sponsorship deals with Gregg Hansford and sidecar star Bob Levy. Tesoriero again: “The format was to be a series of four short races at several of our (WDMCC’s) meetings throughout the year. The races would be held back-to-back, with only refuelling allowed in between. The rules, which Tony Hatton and I worked out, were simple – A Grade riders only, no fairings, standard tanks and seats. We also included a clause that said that riders were permitted one machine change during the series. Over Christmas, I had Ledger work on some designs for this proposed series, and true to form, he came back with some really weird stuff. Ledger wasn’t closely involved in the racing scene, so he wasn’t constricted by the old school or any of the traditions. But one thing struck me when I looked at what he’d done. On the original poster concept, which was full of Frank Frazetta type images of Conan the Barbarian, axe fights and people burning in hell, he had this headline, “The Super heroes, the Super bikes.” This really hit a chord with me, not so much the super heroes bit, but the grids were becoming increasingly filled with big modified CB750s, Triumph Triples, Norton Commandos and so on, rather than the old Manx Nortons and things, and these, in terms of power if not handling, really were ‘super’ bikes. That’s where it came from, and I believe we were the first anywhere in the world to use the term – it was still referred to as Formula 750 in Europe. Some years later the yanks picked it up, but it started at Amaroo Park.”

This last statement is borne out by a statement made recently by US rider and promoter Steve McLaughlin. An interview with Norm DeWitt said, “From discussions with Australian Formula 750 racer Warren Willing, Steve learned of a previous class in Australia called Superbike. Instantly he recognised the name had far greater appeal than the ‘Production’. It (the AMA Series) started as Production, then became Heavyweight Production, then Steve took over the concept and called it Superbike. After much lobbying in 1976 the former Heavyweight Production class was to be known as Superbike, and was raised to championship status by the AMA.” 12 years later, McLaughlin took the idea a further step and created the World Superbike Championship, in partnership with the NZ-based Sport Marketing Company.

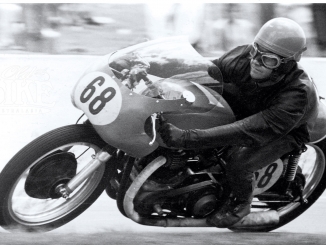

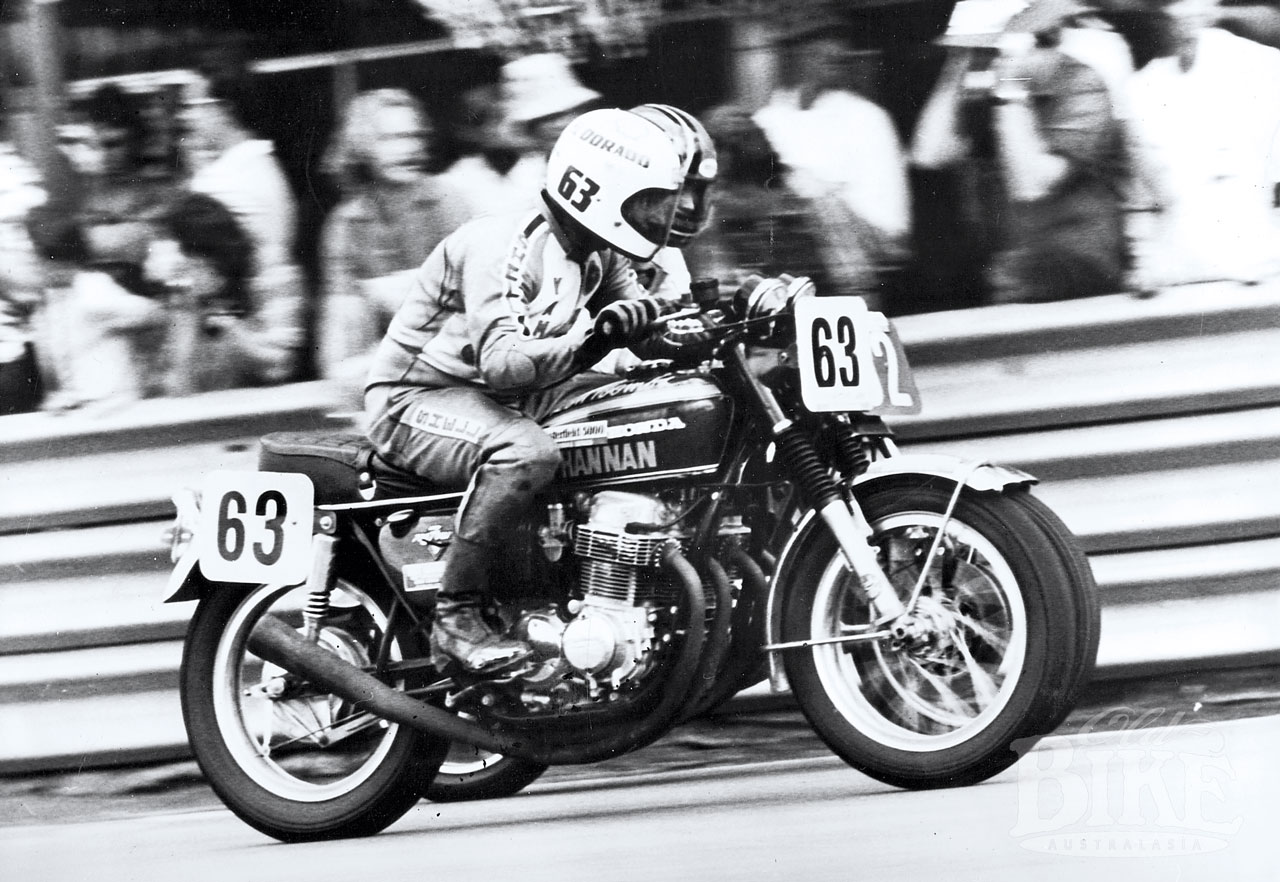

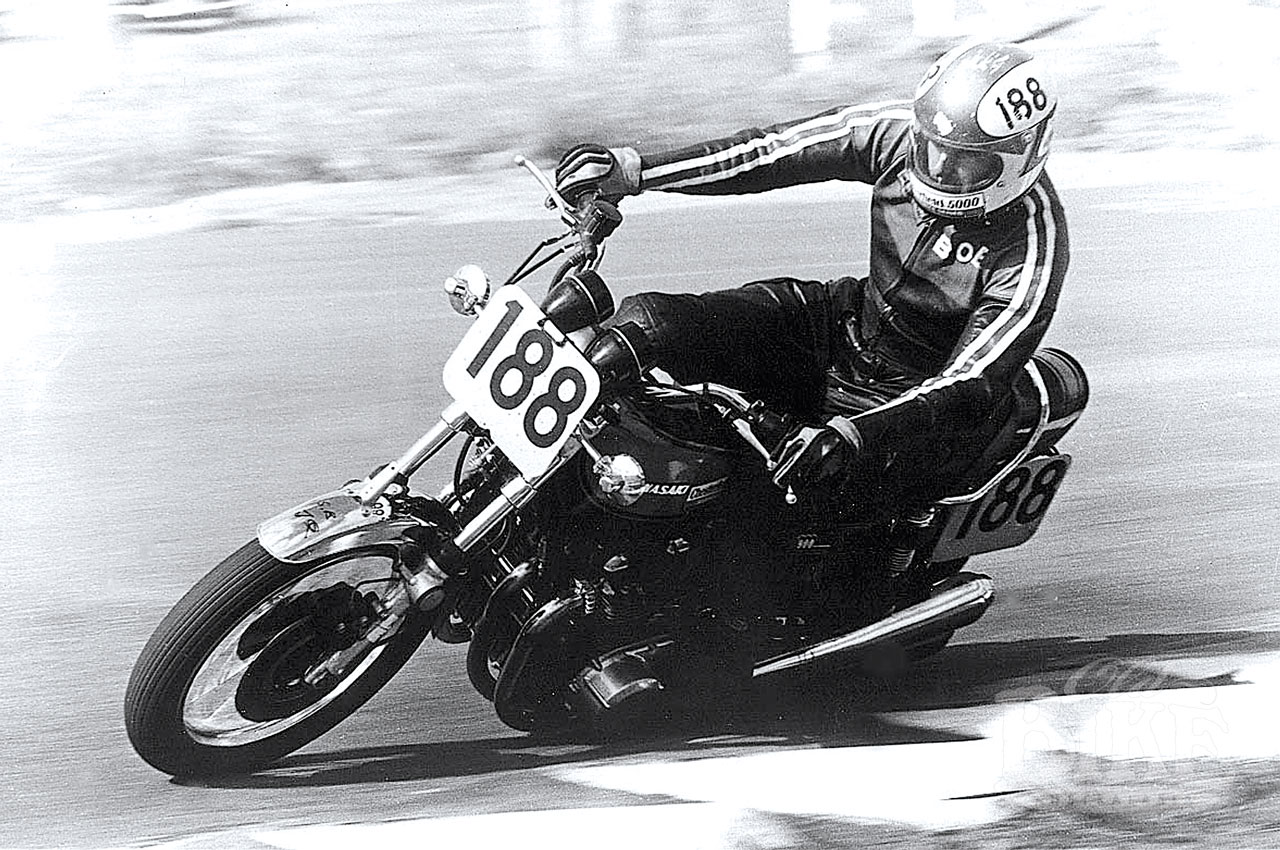

With $5,000 of Chesterfield’s money up for grabs, the series launched as the Chesterfield 5000 Superbike Series, to be held over four race meetings at Amaroo Park, plus a round at the Easter Bathurst meeting. Any and all engine modifications were permitted, fuel was free, as were exhaust system and brakes. Tyres had to be suitable for road use. In reality, the rules were too lax, and were changed after the first meeting. A novelty for the period when the traditional push starts were still the norm, the series employed clutch starts, and at the end of each four-lap heat, the grid reformed with engines still running. The promoters envisaged a grid full of rorty big four strokes, British, Japanese, Italian or whatever, but the reality was somewhat different. Despite the big money on offer, just 14 riders entered for the opening round, and eight of these were on 350 Yamahas – either RD350s or the earlier R5. Except one. Garry Thomas read the rules carefully, removed the fairing from his air-cooled TR350, fitted road tyres, and a tank and seat from an R5 and cleared out for four straight wins. That first round also saw a Norton 750 Interstate for Len Atlee, Vic Vassella’s 750 Laverda, a Kawasaki H2 for Mike Steel, and three Honda CB750s, for

Max Robinson, Clive Knight and Ron Toombs. Ron’s machine was built and owned by Ross Hannan, and featured a four-into-one exhaust culminating in an open megaphone, which Ross says was the first such system made. It made an almighty noise, but the Honda wasn’t quick enough to get Ron into the major results. Immediately after the meeting, the club was besieged with protests, to the point that the results were scrapped. Tesoriero explained the situation. “The series is held over five rounds, and the riders are allowed to drop their worst score, so all the riders who competed on February 18 will automatically drop the first round as their worst score.”

For Round two, on April 1st 1973, the WDMCC committee had rewritten the rules to ban thinly-disguised racers like Thomas’ TR350. All entries now had to be strictly derived from production road-going motorcycles, but internal modifications were still basically free, as were external changes such as exhausts, raising footrests, and brakes. The field was still dominated by 350 Yamahas, and was missing both Toombs and Knight’s CB750s and Vassella’s Laverda. Into the mix came Dave Burgess on a 750 Triumph Bonneville, standard except for rorty megaphone exhausts, and Max Robinson on a CB750. To bolster the grid, selected B Graders were allowed in. Thomas, now on an R5 Yamaha, nevertheless took the first heat from Burgess, Robinson and Atlee. From here on, the four strokes took over, with Atlee taking the next two heats and Burgess the fourth.

The proposed third round at Bathurst nearly didn’t happen, after the NSW A Graders carried out their threat to boycott the meeting after being refused concessions for entry fees. Having put in a huge effort to get the series up and running, Tesoriero was understandably unimpressed. “For the first time ever, a major non-motorcycling concern has agreed to support road racing, and the whole future depends on the inaugural Chesterfield 500 Superbike Series,” he told REVS Motorcycle News. “If it flops this year, Chesterfield certainly won’t be back next season.”

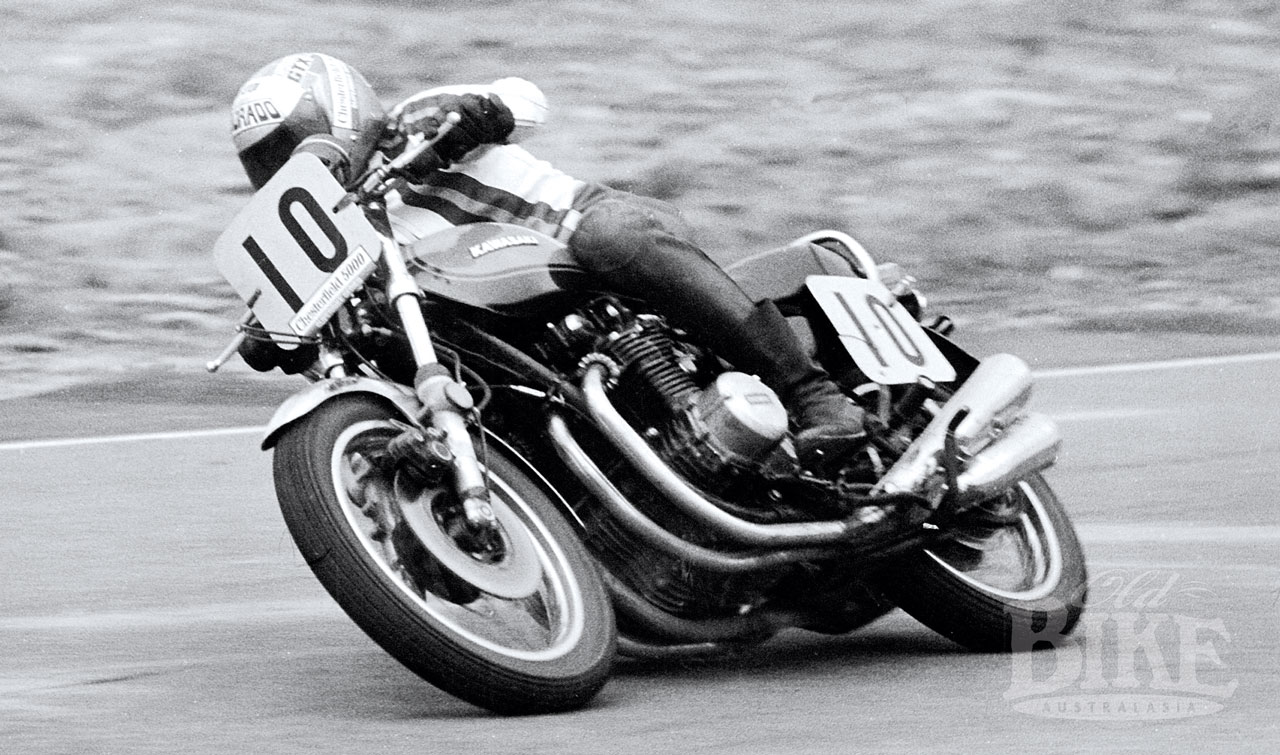

Bathurst went ahead, without the NSW A Graders, and the Chesterfield 500 round did as well, albeit with a much-reduced field. Burgess, who was still a B Grader, was able to enter, but just six bikes faced the starter for the first of two 3-lap heats, and seven for the second. But it wasn’t Burgess who cleaned up, it was Bob Mayes, on the standard Kawasaki Z1 that he rode to the meeting. Each lap Burgess would claw back ground over the mountain, only to see the Z1, complete with indicators and mufflers, disappear on the long straights. Third in both races was Gordon Lawrence on the Fraser’s Ducati 900.

Round Four at Amaroo Park on July 1st was when the concept really came alive. This time the star was Max Robinson, mounted on a new Z1 Kawasaki, and each time he had to fend off the determined Atlee and the big Norton, despite the British twin giving away around 20 horsepower and having only a 4-speed gearbox. Although Robinson won all four races, there was never more than a second in it, and usually much less. Race two saw a monster pile up when Rob Hinton dropped his Yamaha at the fast right hand sweeper, known at this stage as Repco Corner, bringing down Thomas and Bruce Ireland. In the final encounter Atlee pushed so hard that Robinson put in a lap of 59.9 second – 1.8 seconds faster than the existing Unlimited production lap record, for which his Z1 was eligible. Sadly, the likeable Ryde clubman lost his life two weeks later while travelling to Calder for the Two Hour Production Race.

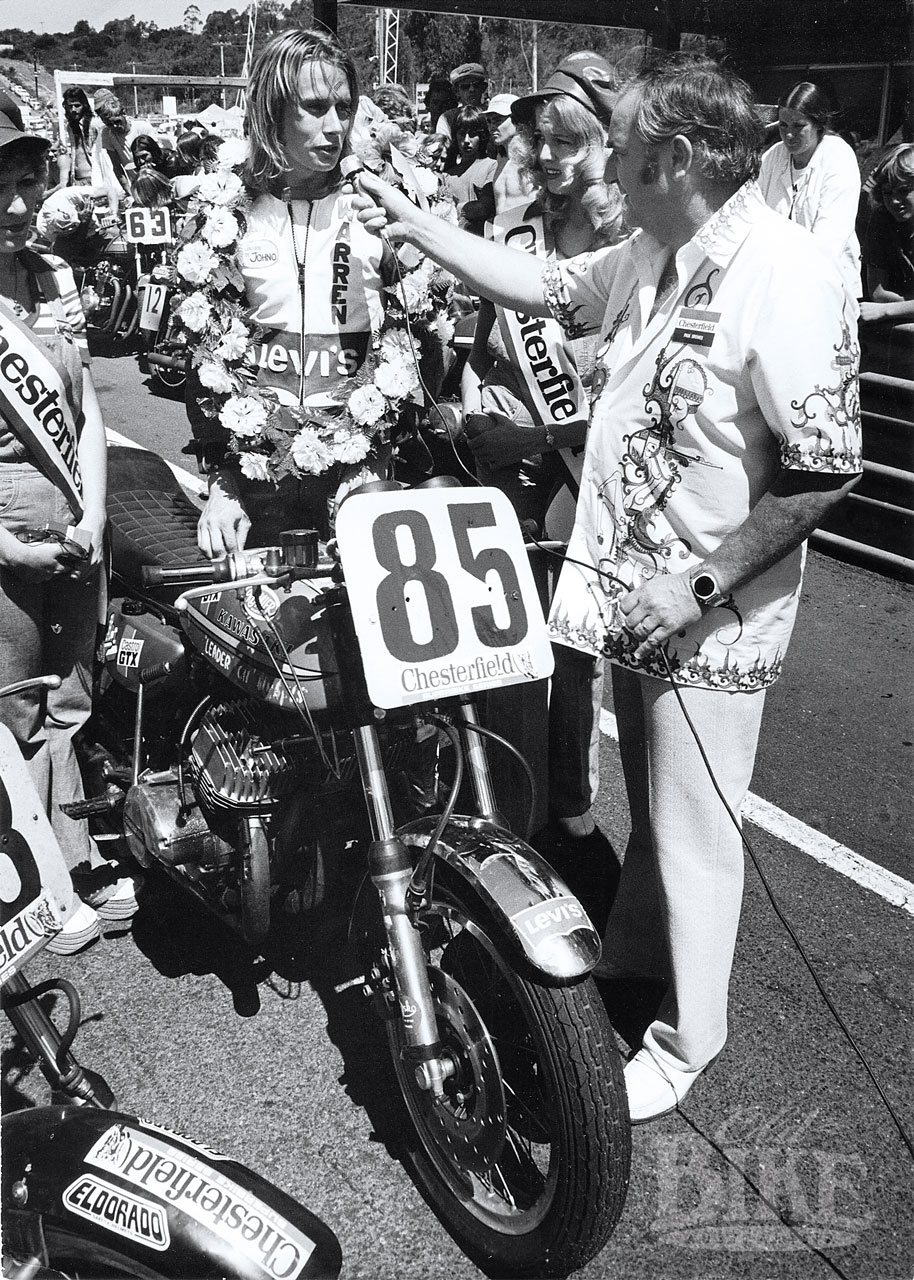

The result had the effect of producing a cliff-hanger points situation for the final round, which was five months away in December. Theoretically, Atlee, Burgess and Thomas all had a chance at the title and the big purse, but Burgess’ chance evaporated when his Triumph refused to run on two cylinders in the opening heat. A quick pit stop (not easy in a four-lap race) rectified the problem and he rejoined the race to finish the last of the seven finishers, which were led by Warren Willing on a Kawasaki H2 he and Alan Adams had built. Thomas was second, having switched to a Z1, with Atlee third. In a determined frame of mind, Burgess blasted into the lead in heat two and led all but the last 200 metres, when Willing out-dragged him to the line. But in heat three it all came unstuck. Trying hard to stay with Willing, but crucially ahead of Atlee, Burgess decked the Triumph at the top of the hill. Riding coolly and calmly, Atlee accepted the gift, cruising home to second behind Willing and claiming the $1,500 first prize in the series – the biggest single purse in Australian racing.

Despite the shaky start, the Chesterfield Superbike Series survived the birth, and for 1974, Willoughby DMCC had even bigger plans.

The second and concluding part of the Chesterfield Superbike Series story will appear in the next issue of OBA (No.23).

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Michael Andrews, Jeff Nield, Allan Rooney.