Around the globe, Gold Star owners and fans rejoiced on June 30th as the 75th anniversary of the feat that led to the creation of the legendary model – Wal Handley’s Brooklands lap.

Few motorcycles receive truly legendary status. You won’t find the Francis Barnett Plover, BSA C10 or a Delta-Gnom in the Hall of Fame, even if there were one, because workmanlike and practical as these models were, they did not possess that certain genius of design to make them anything other than means of transport. But there are certain models where when the name is merely whispered, it is guaranteed to prompt conversation. Vincent Black Shadow, Rudge Ulster and Excelsior Manxman are all examples of high-performance machines that could be purchased by the common man, and all are today regarded with reverence. And to that list must be added perhaps the most enduring and successful sporting design of all – the BSA Gold Star.

In its final – DB/DBD – form, the Gold Star was a striking looking motorcycle; lean and purposeful, thoroughly British, aspired to by a generation of wannabe stars and café racers, and today a true icon of the industry. Even more significantly, the Gold Star’s lineage stretches back to September 22nd 1937, when the model JM24 made its public debut at the Earl’s Court Motorcycle Show. It should have been the star of the show, but in fact turned out to be the co-star, for on an adjacent stand was the equally jaw-dropping Triumph Speed Twin – at £77/15/- a full fiver cheaper than the BSA. But to be fair, the Triumph was a workaday motorcycle, albeit a quick one, while the BSA was aimed squarely at the sporting motorcyclist.

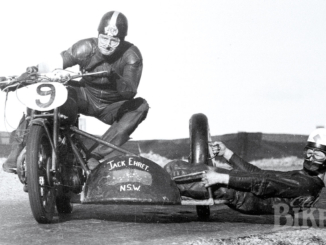

The JM24 had come about as a result of TT hero Wal Handley’s achievement in lapping Brooklands at 107.57 mph in the process of winning a three-lap race at an average speed of 102.27 mph. The accomplishment earned him one of the coveted Gold Stars awarded by the Brooklands promoters for laps above 100 mph. His mount was a factory-tuned iron-engined Empire Star, running on 13:1 compression on alcohol fuel, which he unfortunately chucked away later in the day, breaking his ankle (he never raced again) and damaging the historic machine considerably. Nevertheless, his performance was outstanding, so much so that BSA – despite the company’s official stance of not supporting road racing – decided to market a replica of the machine, to be known as the “Gold Star” in honour of the award from Brooklands.

An undoubted thing of beauty, the ‘Goldie’ bristled with luscious touches like the all-alloy engine, probably the first ever offered on an ‘over-the-counter’ model, chrome-plated lightweight mudguards and a handsome fuel tank with a big golden star motif. As well as the standard model, the M24 could be ordered in two other guises – a Competition (scrambles and trials) model, and a track racing version tuned for alcohol. The engine was a typical (for the time) long-stroker of 82 mm bore and 94 mm stroke. Yet underneath the sparkle, the Gold Star was not exactly earth-shattering, especially in the chassis department. The rigid frame and girder forks were basically identical to the utilitarian M20 which was, and continued to be, the mainstay of the War Department. The gearbox too was M20 – rugged and reliable but hardly a pukka racing job – although the first Gold Stars used a magnesium-alloy casting. Indeed, the Gold Star initially failed to grab the attention of the sporting types, at least in the home market, but it was a different case Down Under.

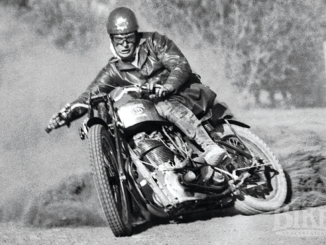

The first Goldie to land in Australia was allocated to Bennett & Wood contracted rider Harry Hinton, and he used it to best effect to win the NSW South Coast Grand Prix at Monkey Flat near Wollongong on March 5, 1938. Hinton had spent the previous five years racking up victories on BSA, as had Eric McPherson and later Tony McAlpine, and this first-up victory on the new model created a rush of orders for Gold Stars. But back in Blighty, where road racing on the mainland was restricted to Brooklands, Donington Park and a few airfields due to a ban on public roads racing, the Gold Star failed to find favour. In fact, there had been an embarrassing situation for the factory when it was discovered during testing that the new alloy head and barrel had trouble getting on together, with oil leaks commonplace. This section of the engine was quickly redesigned with a boss on either side of the cast-in pushrod tunnel and this modification was made to virtually all production models.

If the Goldie had failed to take the road racing scene by storm, the opposite was the case for off-road events. In scrambles and trials the new model quickly became the machine of choice, with Fred Rist winning a Gold Medal in the 1938 International Six Day Trial. But in true BSA form, the sporting Gold Star soon received styling changes to appeal to the touring motorcyclist as well; larger mudguards, oil tank, and a tool box sourced from the M21. As the war took hold, production of the Gold Star ceased, and did not resume until the 1949 model year with the alloy-engined ZB models in 350 and 500 cc form. In fact, the KM24 (the designation for the 1939 model) was officially dropped in 1940, its planned replacement a new 350 to be known as the B29 or Silver Sports, with an alloy engine using integral rocker boxes with hairpin springs. An iron-engined military version of this engine was actually produced – the B30 – and some heads and barrels were cast in alloy and used post war, notably in the 1947 Manx Grand Prix where a B29 with McCandless swinging arm rear suspension was entered. Prior to this, in 1946, BSA produced the trials-model 350 cc B32, joined by the 500 cc B34 two years later, with their own telescopic front forks and an iron engine that responded well to alcohol fuel for hill climbs and grass tracks. When the ZB Gold Star did reappear, it had the rocker boxes cast integrally with the heads. The bore and stroke was now 71 mm x 88 on the 350 and 85 x 88 for the 500. Plunger rear suspension replaced the rigid rear end.

When the Isle of Man TT resumed in 1947, a new event was the Clubman’s TT, with three classes – Lightweight, Junior and Senior – contested in one race over four laps for the two larger classes and three for the 250s. For 1949 it had grown to four with the addition of a 1000 cc class, with all machines required to have kick starters and road equipment with no open megaphones. For 1949, BSA Gold Star riders invaded the 350 class, with 21 of the 74 starters, including the winner Harold Clark. It was a similar story the following year, although the 500 cc ZB34GS was not as popular as the 350. Thereafter, Gold Stars won the Junior Clubman’s and in 1956, every entrant bar one of the field of 55 was Gold Star mounted. From 1954 it had been a similar situation in the Senior Clubman’s, with Gold Stars winning and dominating the entries. It was a case of too much of a good thing, and the TT organisers decided that races entirely made up of one model was not a sound idea, and dumped the Clubman’s races for 1957.

During this period the Gold Star had been progressively redesigned and in late 1952 the BB, with a shorter con rod and larger valves, was introduced. But the biggest visible change was the new duplex cradle frame with swinging arm rear suspension, first seen on the Army Team bikes in the 1952 I.S.D.T. Then came the CB, with its distinctive large finning on the barrel and head, and an even shorter con rod that required the flywheels to be turned oval to clear the piston skirt on the 500. In conjunction with eccentric rocker spindles and nimonic steel valves, power went up to 30 bhp for the 350 and 37 for the 500. A key figure in the Gold Star’s evolution was Eddie Dow, who as an army officer had competed in and organised the Army Teams for the all-important I.S.D.T. each year from 1951. As a racer he was no slouch, although a major accident at the TT detuned him somewhat in his early career before he bounced back to win the 1955 Senior Clubman’s TT, held on the shorter Clypse Circuit. Amazingly, Dow’s machine, with the same tyres and chains, won the Thruxton Nine Hour Race ridden by Dow and Eddie Crooks. When he was discharged from the army in 1956, Dow set up his own shop dealing almost exclusively in Gold Stars and marketing a range of bespoke accessories.

By 1955 the Gold Star had evolved to the DB series, with the flywheels once again circular and the piston skirt shortened. The DB was the Goldie in its most recognisable form, with the handsome maroon-lined silver tank with its chrome side panels and large circular plastic badges, 1 3/16 inch (for the 500) GP carburettor, racing style swept-back exhaust pipe and its distinctive silencer, new slim-style Girling rear shock absorbers, and clip on handlebars as standard fitting on the Clubman model, with rear-set footrests and reversed gear lever. By 1956 the 500 was putting out 42 bhp and breathing through a 1 1/2 inch Amal GP. In the scrambles and motocross fields, the Gold Star ruled supreme for the latter half of the 1950s, with riders like Jeff Smith, Brian Martin, Geoff Ward and Brian Stonebridge to the fore.

The 1956 DBD series, available only as a 500, was little changed from the DB. An alloy 5-gallon tank was available as an option, designed to allow non-stop TT races. The RRT2 gearbox with its extra-close ratios was introduced (four separate choices of internal ratios were offered for racing, scrambles, trials or touring), along with the full-width 190 mm front hub – an alloy hub bolted to a cast iron drum with an alloy backplate. The touring version was finally dropped at the end of 1956. In this form the Gold Star soldiered on for the next seven years, enduring not just competition from other makes, but the machinations of the BSA board, which now controlled Triumph as well, with the irascible Edward Turner at the helm. In the face of the new breed of lightweight trials bikes, the Trials version of the Gold Star was dropped, leaving just the Scrambler and Clubman in production. 1962/63 was the final production year for the model and a strongly-held theory is that its demise was hastened by the decision of Lucas to cease production of separate magnetos and dynamos as design swung more to alternator-equipped unit construction engines.

Every Gold Star underwent testing on the factory dyno as well as a thorough road test. The results of these tests were supplied with the motorcycle when delivered to the owner.

Production figures for the pre-war Gold Stars are vague, but are generally put at between 1,000 – 2,000 per annum, meaning 30,000 – 60,000 in total. For a specialist machine, that’s not bad, and today, good, original Goldies with correct numbers bring big money because this is a motorcycle that rides as well as it looks. A practical classic, to be sure.

Goldies in Australia

Post-war, Gold Stars were imported in reasonable numbers, with the 350 more popular as it gave a ride in both Junior and Senior classes. Probably the most successful road racing Goldie was in fact a hybrid produced by Victorian Jimmy Guilfoyle, using a Norton featherbed frame and ridden to numerous successes by Trevor Pound and later Brian Beasy. Ken Rumble was synonymous with the model, the great all-rounder collaring national titles in Scrambles, Short Circuit and Road Racing. Ron Toombs began his rise to fame on his own 350 Gold Star which was later joined by his mate Tony Henderson’s 500. Future World Champion Tom Phillis also honed his skills on a Gold Star before graduating to Nortons.

In Scrambles, Gold Stars dominated the national titles for many years. West Australians Peter Nicol, Charlie West, Alan Nicol, Bob O’Leary, Gordon Renfree and Ron Edwards, South Australians Jim Silvey and Graham Burford, and Victorians Ray Fisher and John Burrows all took national Scrambles titles on Goldies.

But the model’s most significant contribution was to give the average Clubman rider a competitive and reliable mount, and with local rules permitting the use of alcohol fuel, one that could give a reasonable account of itself in open competition as well. Of course, a vast number of Gold Stars never went racing at all, providing their owners with a glamorous and high-spirited steed for road burning.

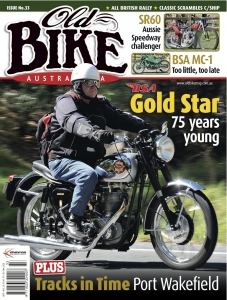

Let’s try one

John Mikutta is a BSA man through and through. His stable includes the luscious Road Rocket featured in OBA 32, plus a 1952 plunger-framed B33. His Gold Star is a 1956 DB34 in completely original Clubman’s trim with the exception of the Phil Pearson 5-speed transmission and belt primary drive. The standard close-ratio four speed box is a major impediment to enjoyment when using a Gold Star on the road, and this modification vastly improves the rideability. To the naked eye there is nothing to distinguish the DB to the later DBD model, and John’s bike features the big Amal GP with remote bowl that was de rigour for road racing, as well as the 8-inch front brake. This brake is actually bigger in diameter than the more fabled 190 mm job, but the shoes are narrower so the full-width hub gives a bigger braking area. However there’s nothing wrong with the stopping power of the narrower item, and to my eye, it actually looks better as well.

Despite the big carb, the Goldie fires up easily and the mixture is obviously spot-on, as it pulls cleanly away with no spitting or snatching. That lower first gear certainly helps as well, because the close-ratio 4-speeder requires much clutch slipping and deft throttle usage, something that gets fairly tedious in normal riding. The route took us up into the hills north of Adelaide, and you couldn’t release a Goldie into a more suitable environment. The big single fairly laps up the twists and turns, and I am pleased that John’s machine is fitted with conventional handlebars and not the clip-ons and rear-sets favoured by the white-scarf set. This gives a very comfortable riding position, although John like his handlebars turned up at an angle that I found a bit tiresome on the wrists. The seat is firm but comfortable, and the whole riding position is a naturally tucked-in style thanks to the narrowness of the seat and the two-gallon steel fuel tank.

The bark of the trademark silencer made wonderful music as we scooted up and down the hills, with that characteristic ‘twittering’ on the over-run. The silencer is actually designed as a megaphone with a short straight stub to finish, and this came about due to Clubman’s TT regulation that demanded a ‘standard’ exhaust system. Whatever the actual specification, it ain’t a real Goldie unless it ‘twitters’!

John has fitted an Avon Speedmaster front and a Dunlop TT 100 rear tyre, a good choice which looks right and works well. Needless to say, the handling is exemplary, with both front and rear suspension doing their jobs to perfection. Had it not been for traffic and the need to keep an eye out for Mr Plod on this road that is somewhat of a motorcycle playground, especially on weekends, the temptation to really give it a blast would have been overwhelming.

Of course, the Goldie has good looks by the bucket load, and is guaranteed to draw a crowd whenever it is parked. My thanks to John for the opportunity to gallop a real thoroughbred in a perfect environment.

Recognising a Gold Star

There is much confusion over what exactly constitutes a Gold Star, as there were alloy-engined B32 and B34s produced simultaneously.

The first post-war Gold Stars were the ZB32 and ZB34 series, with a connecting rod 7 3/8 inches between the centres. From engine number ZB32GS-6001, the 350 cc ZB32 rods measured 6 7/8 inches. For 1953 and 1954 the numbers changed to BB32GS and BB34GS for the standard model, and CB32GS/CB34GS for the Clubman’s and racing models. Just to confuse the issue, the CB series engines were also fitted to scrambles and touring models in 1955. The C series engines had the shorter rod of 6 15/32 inches with bigger head and barrel finning, eccentric rocker adjustment and revised inlet and exhaust port shape.

The DB32GS and DB34GS were introduced during 1955 as Clubman and Road Racing models, and late in the year to Scramblers and Tourers as well. 1956 marked the introduction of the DBD series for Clubman’s and Road Racing models. From 1959-63 a 500 cc model known as the Catalina was produced for the USA market. The final 1963 models began with engine number DBD34GS 6881 and frame number CB32 11001.

Post war, rigid frames carried the prefix ZB31 with ZB31S for the plunger – except for 1953 models which are BB31 and BB32S respectively. All swinging arm Gold Star frames are prefixed CB32.

Canberra enthusiast Peter Davey has an enviable stable of classic bikes, including the Douglas featured on the front cover of OBA 5, and his well known BSA Y13 V-twin. During a visit to the Isle of Man last year, Peter took delivery of some additions to his BSA stable – a Y12 twin and a BSA Gold Star. The latter is significant in that it was delivered in racing specification for the IoM Clubman TT races. The first swinging arm model with the ‘fat’ Girling rear shocks, Gold Star engine number BB34 GS459/frame number BB32 A 238 left the factory on October 1st, 1953, bound for Portsmouth UK dealer Glanfield Lawrence. Noted on the delivery sheet was that the machine was supplied with a 4-gallon petrol tank, and the factory test sheet shows it was tested with a straight through exhaust pipe, on castor oil, and fitted with a Mag Dyno, producing 27 hp at 5,800 rpm and 26 ft/lb torque.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Keith Ward, Charles Rice, Jim Scaysbrook