Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Sue Scaysbrook

For Benelli enthusiasts, there is a definite line in the sand in the company’s heritage; in reality, more a deep trench than a line. That is the point when the famous brand was acquired by flamboyant Argentinean entrepreneur Alejandro de Tomaso in 1971. Taking a long, hard look at the four cylinder Honda CB500, de Tomaso instructed his design team to come up with a Latin equivalent, which emerged as the Benelli Quattro. The new Benelli was virtually a copy of the Honda, save for the cylinders being canted forward by about 15 degrees instead of vertical as on the Honda. The styling was the work of Carrozzeria Ghia, and to strike a visual difference from the CB500, the cylinder and cylinder head fins on the 500 Benelli were squared off in the form of the company’s previous GP racers.

It was a far cry from the beginnings of the Benelli marque, which started in 1911 as a Pesaro garage and repair business. In 1913 they produced a 75 cc two-stroke engine designed to be fitted to a bicycle, and in 1921 they took the full step to making their own complete motorcycle. Racing success followed, as did a string of highly innovative designs – their four-stroke 175 of 1929 becoming almost unbeatable in the class in Italy. During the ‘thirties, Benelli produced a string of beautifully engineered OHC racers, with a look-alike 500 road bike, but then came WW2 and the factory was all-but destroyed. With typical resilience and determination, Benelli was back in business by 1946, and its gorgeous DOHC 250 dominated the 1950 World Championship in the hands of Dario Ambrosini. When Ambrosini crashed fatally in the following year’s French GP, the factory lost heart and withdrew from international racing.

Despite the later successes that included Kel Carruthers’ 1969 250 World Championship, Benelli was in deep trouble, lurching from crisis to crisis (including a fire at their Pesaro factory that did much damage), and although the racing team soldiered on with Renzo Pasolini, the commercial side of the business was moribund.

And so, in late 1971, in stepped de Tomaso, fired up with his Ford-backed successes (and occasional failures) in the four-wheeled world, and Benelli was off on an entirely new tangent. The road bike line up initially included 125 and 250 two-stroke twins, plus the 653 cc OHV vertical twin, sold as the Tornado in USA. The unit-construction big twin was a well made machine that gained a foothold in both the US and UK markets, but by this stage the customers were clamoring for ‘fours’.

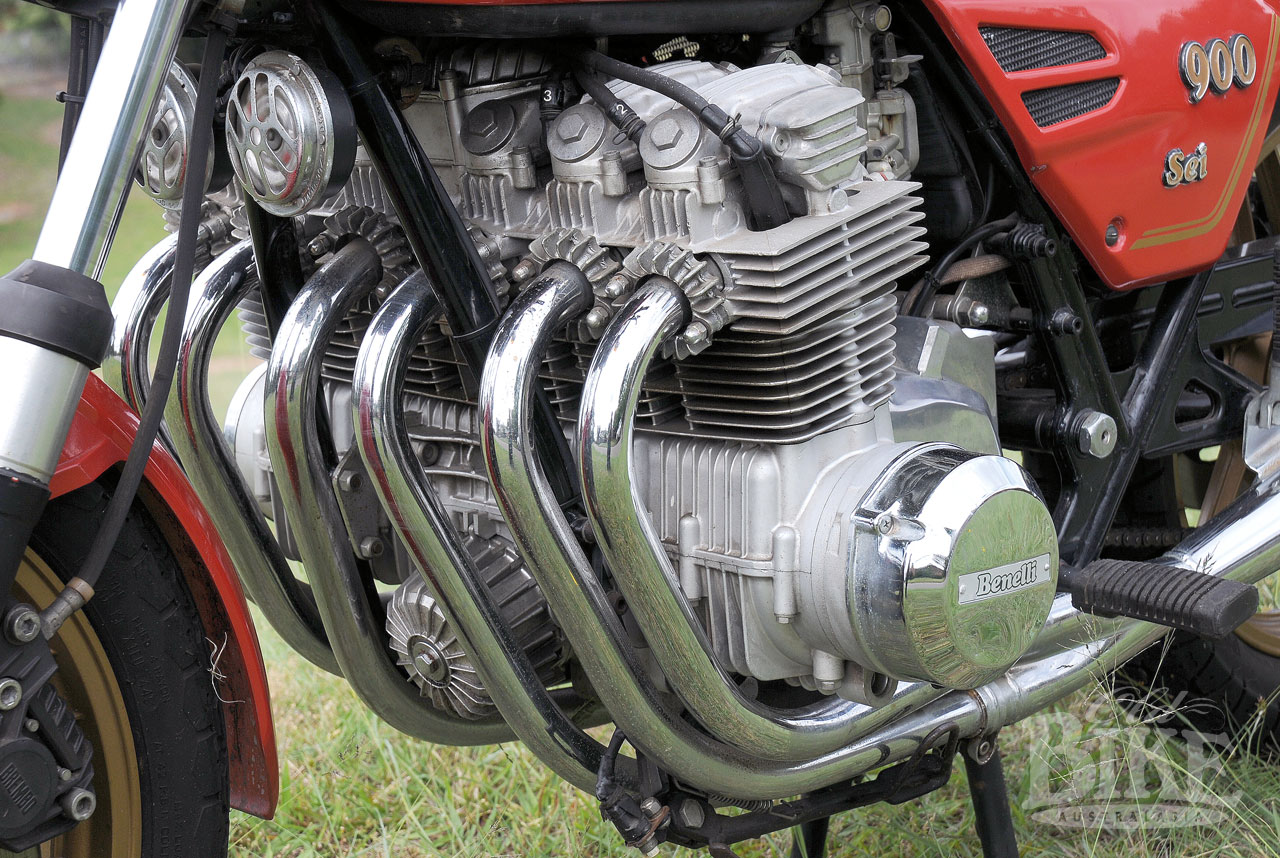

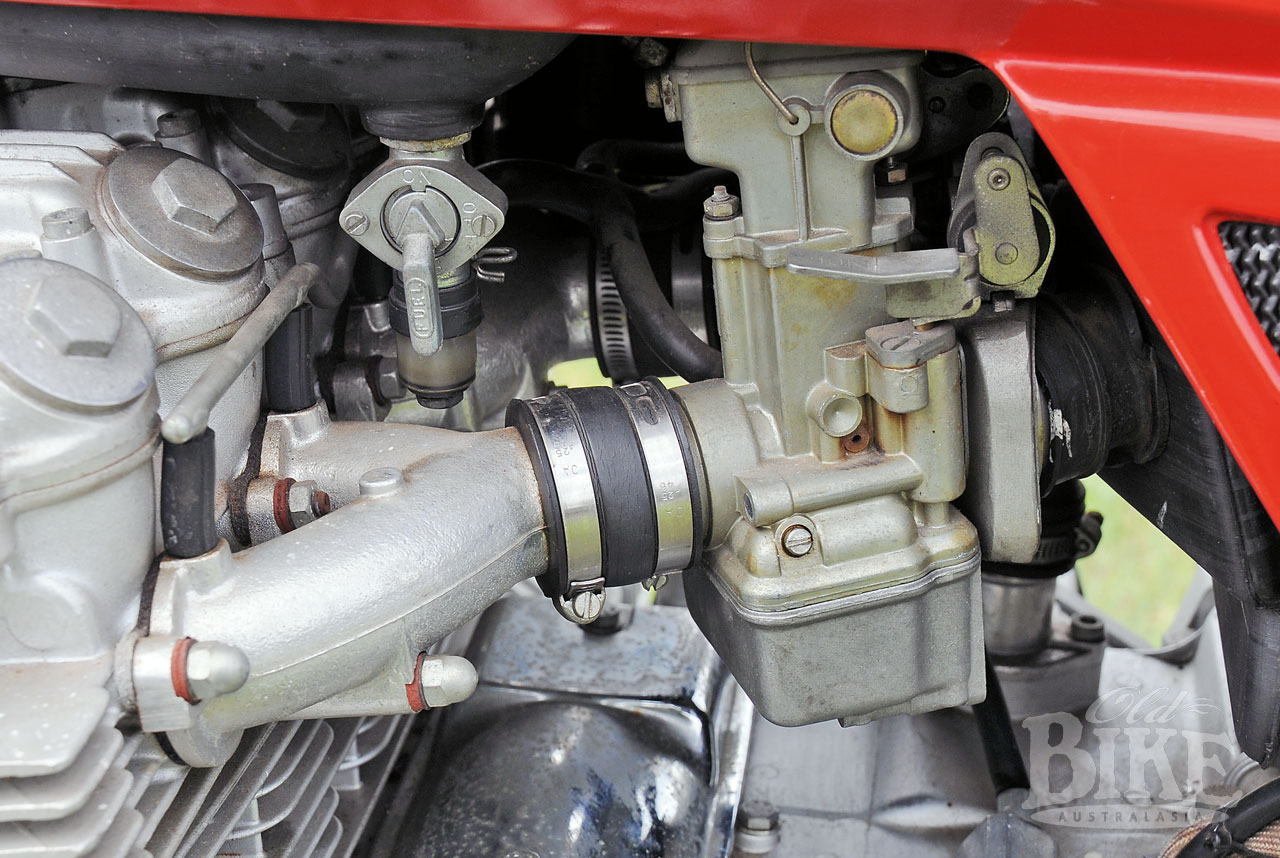

With typical bluster, de Tomaso announced he was ‘declaring war’ on the Japanese factories with his new range that was advertised as, “The Italian Alternative”. The 750 Sei (Italian for ‘six’) was rightly proclaimed as the first-ever production six-cylinder motorcycle, achieved by the simple expedient of hanging another cylinder on each end of the 500-4’s crankshaft. Although it was never admitted as such, the heritage of the CB500 Honda is evident even in the 750-six. Bore and stroke of 56 mm x 50.6 mm is identical, as is the method of running the cam chain in the centre of the engine to the single overhead camshaft, the Morse Hy-Vo primary chain and the plain bearing big ends. Unlike the Honda, which had the alternator on the end of the crankshaft, the Benelli designe positioned the alternator behind the cylinders, together with the starter motor, while the points ran from the left side end of the crankshaft. The engine breathed through three Dell’Orto VHB 24 mm carburetors. The one-piece crankshaft, with crankpins set at 120 degrees, is supported by seven main bearings with plain big ends.

However if the powerplant had its roots in Japan, the cycle parts were unmistakably Italian. A neat double cradle frame, Marzocchi suspension front and rear, twin Brembo front disc brakes (the first Brembo brakes to be employed on a production motorcycle), and Borrani alloy rims for the spoked wheels were all top-shelf stuff. The model was unveiled on October 27, 1972 with typical de Tomaso fanfare at the Grand Canal Hotel in Modena, but after doing the rounds of the shows and exhibitions, it was almost two years before production models reached dealers’ showrooms, and by 1974, the 750 Sei had a lot of catching up to do, because the Kawasaki Z1 was now well and truly the yardstick and selling like hot cakes.

Early road tests praised the styling and handling of the 750 Sei, although most were fairly unimpressed with the modest power output, around 75 hp. The biggest impediment to sales success was however, the price – almost double the asking price for the CB750 and Z1. With the booming Japanese sales there was also the problem of setting up a suitable dealer network – something that was never satisfactorily resolved.

Having a stroke

De Tomas’s ‘war’ turned out to be little more than a minor irritation to the Japanese as the 750 Sei trickled out of the factory. Official figures put the total output between 1974 and 1977 as 3,200, but Benelli refused to give up. Announced for 1978, the 900 Sei was a completely restyled machine, with a larger bore of 60 mm bore and a longer stroke of 53.4 mm stroke to give 906 cc.

By this stage the Benelli had not one, but two opponents in the six-cylinder category; the Honda CBX, with four valves per cylinder and double overhead camshaft, and the Z1300 Kawasaki, an entirely different slant of the half-dozen concept, and water cooled to boot. By comparison, the Sei was underpowered, a little over weight (254 kg) and expensive, but it was…Italian. Handling was in keeping with the 750 Sei heritage, perhaps better given the up-rated Marzocchi suspension with 35 mm forks, Campagnolo cast-alloy wheels and the latest Brembo dual-piston stoppers up front. In the styling area, Benelli had certainly started with a clean sheet of paper; the fuel tank is actually contained beneath a shroud which also forms the side covers in an angular swoop, with a glass fibre shroud for the seat and tail. And visually, the Sei was, compared to its rival, svelte, with none of the massive bulk associated with the Kawasaki, nor the excessive width of the Honda. Gone was the evocative set of six individual megaphone silencers, and in its place a rather conventional pair of three-into one pipes, made by specialists Silentium. The former rear drum brake became a disc, and there was now a sidestand, complete with a switch that required it to be in the ‘up’ position before the engine could be stated. One very unique departure from the 750 was the double-row rear chain and associated sprockets; the smaller links supposedly providing better life for both components. This may have been fine in theory, but many of the 900s that were sold had the final drive converted to conventional (and far cheaper) single row chain and sprockets by dealers.

Riding the Sei

This 900 Sei has just 2,300 kilometres on the clock from when it was sold new in Melbourne in 1982. Well known collector and motorcycle identity Ivan Cason fills in the background: “This bike cost $9,300 new, and the bloke who bought it rode it from Melbourne to see his daughter at Emu Plains (west of Sydney) just near me. By the time he got here he had had enough of it because he couldn’t pull the clutch in. He went around all the dealers in Parramatta to trade it in, but he couldn’t even get $5,000, so he bought a new Japanese bike to ride back to Melbourne and left the Benelli with his daughter. In the those days I used to hold bike shows in aid of charity at my place and his daughter came along and told me about the bike, so I gave her $5,000 for it. I only rode it once, just out to Springwood and down the Hawkesbury Hill and I could see why he didn’t want it, I couldn’t pull the clutch in either! Since then it has just sat in my garage.”

With that sort of a wrap, I just had to try this machine for myself. The 900 Sei does not feel like a big bike, because it isn’t. In fact the six-cylinder engine is only fractionally wider than a Honda-4. The riding position, compared to the contemporary Japanese offerings is rather pedestrian, with the footrests well forward, meaning you also sit well forward and upright. Maybe this is why the seat extends up the rear of the petrol tank, in the manner pioneered by Honda for its early XR trail bikes. Looks a bit funny on a road bike, though.

The first shock comes when it’s time to engage first gear. Pulling in the clutch definitely requires fingers strong enough to crack walnuts, and makes it difficult to release the lever smoothly. The actual clutch action is fine, but it comes down to your ability to manipulate the lever. This is apparently a factory reaction to the initial criticism of the model (mainly by road testers doing standing starts on drag strips) that showed the small, dry clutch was prone to slipping if treated harshly. The factory sent out kits with stronger springs and clutch friction plates with a different texture, which were fitted by dealers under warranty. Subsequent production had the up-rated clutch kit fitted from the factory, and it certainly cured any tendency to slip, but I think under normal day-to-day operation the original clutch (as fitted to the 750 Sei) would be quite adequate and much more pleasant to use.

The small fairing was also modified from the early models because of criticism that it made the instruments difficult to read, and this one does a good job of deflecting the breeze at normal speeds, while giving a clear view of the speedo and tacho, as well as the cluster of little coloured lights that indicate various functions. In the short time I had to ride the 900 Sei, the Italian breeding becomes instantly apparent. This bike could not have come from Japan; it’s not something that you can put your finger on, just a certain je ne sais quoi. I found the rear suspension much too soft, but the front worked well and the brakes, in their day, must have been considered quite special.

The engine is deceptive. There’s really nothing that tells you that you’re aboard a six-cylinder masterpiece of engineering – it could well be a four – but it is certainly smooth and vice-free, although it doesn’t feel excessively powerful. Probably as a result of the prevailing emission laws, the 750’s raspy shriek from the six separate exhaust pipes is muted and mellow via the 900’s twin-muffler system, which is a bit of a shame, because the sound of a small-capacity six singing is sweet indeed. Despite the quirks, the 900 Sei is a very pleasant (apart from the cutch) machine to ride, and this one would be even better with some fairly minor attention to the rear suspension.

There’s no doubt though, for sheer panache the 900 Sei is hard to beat and would attract an instant crowd at any rally. Although a far cry from the jewel-like creations of the company’s glory days, the 900 represents a distinctive chapter in Benelli’s history, and one with more going for it than the products that appeared a couple of decades later in a somewhat sorry stage of the company’s rocky road.

A big thank you goes to Ivan Casson, several of whose lovely bikes have appeared in Old Bike Australasia before, for the opportunity to sample this Latin lovely.

1982 Benelli 900 Sei – Specifications.

Engine: Air-cooled SOHC transverse six, 2 vales per cylinder

Bore x stroke: 60 x 53.4 mm = 906 cc

Compression ratio: 9.5:1

Induction: 3 x 24 mm Dell’Orto carburetors

Ignition: CDI, electric start

Power: 80 hp (58.3 kW)@ 8,400 rpm.Transmission: 5-speed, duplex final drive chain.

Suspension: Marzocchi front fork. Marzocchi rear shocks with 5-way preload adjustment.

Brakes: Front: 2 x 294 mm discs with brembo 2 piston caliper

Rear: 1 x 255 mm disc with single piston Brembo caliper

Wheels/tyres: Capagnolo cast-alloy, front tyre 100/90 x 18, rear tyre 120/90 x 18

Weight, wet: 254 kg

Fuel capacity: 16.5 litres

Top speed: 195 km/h