Saturday July 30th, 1955 was a tumultuous day in the history of motorcycle Grand Prix racing. For a bunch of Australasians, it marked a watershed in their careers.

It’s a tough life being an international motorcycle racer. It always has been. Today’s aspiring world champions face the same dilemmas as their predecessors in that they must endure the travails of their profession long enough to prove themselves to the big teams, and try to avoid starving along the way. And today, the majority of the field, even in World Championship events, is on the grid solely because the riders have stumped up a fat wad of cash to secure themselves a berth in a team.

Sixty years ago, the story was much the same, except that there were very few teams – just a handful of works squads with hand-picked top riders – with the vast bulk of the starters made up of impecunious privateers who literally lived hand-to-mouth, weekend to weekend. It was simply the love of the sport that drove these men (and women), plus the chance to enjoy a lifestyle that offered travel rather than the drudgery of a job in a factory. And then there was the danger – ever-present and very real.

It was particularly galling for this band of troupers with their battered ex-army vans crammed with the tools of their trade, cooking and camping gear and very little else, to see the promoters raking in huge takings at race meetings on the strength of the show they were providing for virtually nothing. Perhaps the most vagrant flaunting of this arrogance was the annual Dutch TT at Assen, where a sell-out crowd was a foregone conclusion. As it was part of the FIM World Championships, anyone with such aspirations was compelled to enter this meeting, the history of which stretched back to 1925, and the organisers (and the Royal Dutch Motorcycling Federation or KNMV) knew it. The privateers, the majority of which had little hope of finishing in a position that paid prize money, relied on the starting money offered by the promoters entirely at their whim.

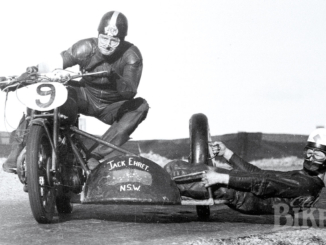

In 1955, there were a disproportionate number of ‘Commonwealth’ riders on the Continent, drawn mainly from Australia and New Zealand but also from South Africa, Canada and even Ceylon. Of these, a handful including Ken Kavanagh and Ray Amm had managed to gain positions in factory-supported teams, but for the rest it was a struggle even to get to the meetings, let alone feed themselves.

Arriving at Assen in the week preceding the races to be held on Saturday 16th July, 1955, the motley crew of privateers set up their camp as usual. In the preceding twelve months since the 1954 event, the Assen circuit had been totally rebuilt, reducing the lap distance from over 22 kilometres to 7.7. The organisers made much mileage of the change, stating that it was performed primarily with the interests of the competitors in mind, but most saw it as a commercial exercise – the shorter course allowing almost total control over the egress of paying spectators which had not been possible with the former circuit that ran between the towns of Barteldbocht, Hooghalen, and Laaghalerveen. Citing the expense involved in the construction of the new circuit, the KNMV refused to increase the already pitiful starting money over the 1954 amount, leading to much rancour amongst the privateers, and indeed, sympathy from some of the works riders as well.

Prior to the Saturday race day, a petition began circulating in the paddock, ostensibly organised by a group of local Dutch riders who had failed to qualify, and hence had been refused their ‘starting money’. This grew into a major revolt when the petition was extended beyond the claims of the Dutch riders to be allowed to start and thus collect their money, to include many privateers who felt that their own starting money was inadequate to warrant racing at all. News of this potential uprising reached the General Secretary of the KNMV, Mr Burik, who said later “I ordered some officials to make an inquiry unstrikingly (sic). After about half an hour it was reported that no official action could be observed, especially with the Dutch drivers.”

Whether the officials could find evidence of unrest or not, it certainly existed, as was demonstrated forcibly in the 350cc race. After just one lap, thirteen riders pulled into the pits and ‘retired’, having officially qualified for their money by actually starting in the race. Amongst these riders were Australians Jack Ahearn, Keith Campbell, Tony McAlpine and Bob Brown, and New Zealanders John Hempleman, Barry Stormont and “Peter” Murphy. One lap later English rider Arthur Wheeler also retired. While the riders disappeared into the back of the paddock, outraged Dutch officials swarmed everywhere, while the confused spectators sat through a mock race which concluded in a ‘formation’ finish by the works Moto Guzzi team, led by Kavanagh. Soon, a delegation of the privateers informed the Clerk of the Course that a similar action was likely to take place in the 500cc race unless their demands for increased starting money were met. After a hasty conference, the KNMV responded with a slightly increased figure, which was rejected by the riders.

More worrying for the organisers was the fact that the animosity had spread to the star attractions, the works teams from Gilera and MV Agusta. Although a multi world champion, Geoff Duke was one of the most approachable and respected members of the riding fraternity, and when approached by a number of the privateers, he agreed to speak to the Gilera team manager. Word quickly reached Burik that Gilera and MV Agusta would be supporting the private riders, and faced with a debacle and the prospect of a near riot amongst the paying spectators, they agreed to meet the riders’ demands. This happened mere minutes before the scheduled start time, and although the race went ahead with the full field (won by Duke with Australian Bob Brown scoring the best-ever result for a Matchless G45 twin with fifth place), the KNMV was seething.

The Dutch federation made an official complaint to the FIM, which listed the item on its agenda for its annual congress later in the year. In his report to the FIM’s Commission Sportive Internationale, Burik stated, “ About half an hour before the start of the 350cc class, which was due to start at 11.30, the Australian driver (Tony) McAlpine came to me and informed me confidentially about a question which he called very annoying. He told me that several foreign drivers were discontent about their starting money and, to show their discontentedness, had made up their mind to stop in the 350cc race after the first lap. McAlpine was also asked, as he told, to join this action. He pretended that he felt himself in an awkward position, for on one side he agreed with the drivers that starting money was too low, but on the other hand the Promoters had offered him 25 guilders more than he had asked for. Therefore he himself could not complain about his starting money and so far he had not yet decided if he should join the action. In any case he found it necessary to inform me. After this I immediately informed the Promoters, who explained that they had received not a single complaint, that it was practically impossible to deal with the question just now, and that the best thing to do seemed to wait and see what should happen.”

In the panic that followed the 350cc ‘strike’ a hasty meeting of riders’ representatives and the promoters was convened. The riders demanded an extra £20 per start (including their aborted 350cc race) while the promoters countered with an offer of a flat £15 extra for the entire meeting. No deal, said the riders. Burik continued in his report, “On this moment (Geoff) Duke appeared and took part in the discussion. I told him what had happened and explained that every rider who had presented himself for participation in the Dutch TT had received an offer from the organisers to take part for so and so much start of money. All drivers had accepted and sent their entry forms. Therefore it was highly undecent (sic) to threaten with a strike on this moment also in the 500cc class, especially towards these organisers who had struggled for months without personal interest to have this new circuit ready in due time. Duke explained that the drivers had very great and raising expenses; their machines were much more expensive, prices of spare parts went up considerably as well as the cost of living, etc, etc. In spite of the enormous public, lower starting money was paid here and that was, in his opinion, shameful. One had to keep in mind that it were not the drivers who had asked for the new circuit (said Duke), so one should not let the drivers pay for it.”

In a statement later strenuously denied by McAlpine, Burik claimed that he had been told by some Dutch riders that McAlpine had said he would “sweep them off the course” if they did not join in the strike. Burik also stated that prior to the scheduled start of the 500cc race, “Duke came to the timekeepers’ house, accompanied by (Gilera team mate) Armstrong and (MV riders) Colnago, Milani and Masetti and asked me what the last word of the Promoters was, and I answered that they maintained their offer of £20 extra per driver, not per start. Duke then declared, also in the name of (the four others), “We works riders will start in the 500cc race and stop after the first lap unless the Promoters agree in raising the starting money with £20 per start.”

Those words were to cost Duke dear.

In the maelstrom of activity that followed the Dutch TT fiasco, many meetings were convened by the FIM and CSI, each becoming increasingly acrimonious. Finally, an Extraordinary meeting of the CSI was convened on 24th November, 1955 in London, “to investigate and finally settle the case.” Duke refuted the Dutch claims that they knew nothing of the riders’ demands prior to the race day itself, stating that he had personally informed the organises several days before of the disquiet. Of the affected riders, only Armstrong, Duke, McAlpine and British privateer Phil Heath attended. At the conclusion of a tumultuous and noisy meeting (at which Duke conducted himself with his normal aplomb and good grace), the Secretary General of the CSI urged members to accept an apology from the riders to allow the case to be settled, but this was rejected. In a vote, delegates (including from the Auto Cycle Union of GB which also represented the interests of the Australian and New Zealand riders) voted 7-1 for six months suspension for the privateers, and for Duke and Armstrong, while the Italian riders received a four month suspension, commencing 1st January 1956. Only the Irish federation voted against the suspensions.

It was a body blow for the ANZAC privateers, as it meant missing all of the Grands Prix and international meetings (including the Isle of Man) in the first half of 1956. As ACU licence holders, the ban applied even in their home countries. McAlpine and Hempleman retired from racing (Hempleman only briefly), and Ahearn quit Europe for two years. Campbell, Brown and Peter Murphy went back to Europe, and in April, the FIM relented to allow them to compete in races not counting for the World Championship.

For Duke, a man at the peak of his powers as a rider, the suspension marked a watershed in his career. After sitting out the first half of the year, he uncharacteristically crashed in the Ulster Grand Prix but won the final GP at Monza – his last as a works rider.

As Duke said in his autobiography, “ The only good thing to come from the Dutch incident was that at the conclusion of the extraordinary meeting of the CSI on Friday 25th November, 1955, a draft regulation concerning the stipulation of, and agreement to, the amount of starting money offered at international road race meetings was presented to the meeting. Detailed discussion was deferred until the subsequent Spring Congress held in Oslo, but the regulation later became obligatory.”

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Keith Bryen, Dave Kenah, OBA archives.