Tony McAlpine had a reputation for being a forceful character, both on and off the track. From the time he first appeared as a teenager in Miniature TT (unsealed circuits) around Sydney in the late 1930s, he was instantly recognisable for his all-action style. None of the neatness of a Harry Hinton or Eric McPherson for Tony; his technique was wide-open and sideways.

By the time World War 2 had ended and motorcycle racing was back on the weekend agenda in Australia, Tony had matured from the tearaway youth to a well-built and handsome young man, with the dark eyes and complexion of his Italian mother. His need for speed had not abated with the years either; Tony craved the biggest and the best. Les Warton had been cleaning up the sidecar class ever since taking delivery of a Vincent HRD Rapide, and Tony decided he had to have one. In June 1949 he took delivery of a new Vincent Black Shadow and began a remarkable rise that took him to the very top of Australian road racing. Success followed success: the Queensland TT at Leyburn, the Victorian GP at Fishermen’s Bend, The Victorian TT at Ballarat, and the big one, the Australian Unlimited TT on Boxing Day in South Australia’s Barossa Valley. Tony was The Man, but he wanted more. Although his Australian TT win meant he was the official national champion, the annual Easter meeting at Bathurst was far and away the biggest event in the country.

Anticipating a clash of titans, 30,000 spectators poured into the town to see McAlpine take on Harry Hinton, Jack Ahearn, Bat Byrnes and fellow Vincent rider Lloyd Hirst. The ballot for grid positions saw the star riders sprinkled throughout the field for the 20-lap, 120 kilometre NSW Open Grand Prix, but by the time the first lap had been completed, it was McAlpine and Hirst at the front and pulling away. Setting record lap after record lap, Tony’s first set back came when the strap on his goggles snapped, but he pressed on regardless. Hirst was in trouble when his fuel tank was overfilled at his pit stop and the engine refused to restart. Then, with the race in his pocket, McAlpine’s Vincent snapped the drive chain as it powered up the mountain and his race was run. His only consolation was a new outright lap record of 3 minutes 4 seconds.

It was about this time that Tony made another decision; to try his luck in Europe. Crucial to the funding of the trip was to receive an official nomination from the Auto Cycle Council to represent Australia. This carried a stipend plus a certain amount of assistance from the ACU of Great Britain. Tony’s credentials were impeccable and he duly got the nod, along with Ken Kavanagh and Harry Hinton. Then there was the question of machinery to consider. The Vincent was not suitable because of the 500cc capacity limit for most international races, so it stayed at home. Tony ordered a 350cc 7R AJS for the Junior class, but what about the Senior? The thought of joining just about everyone else on a Norton didn’t appeal, but what was the alternative?

Never the shrinking violet, McAlpine decided to approach the Gilera factory in Arcore, near Milan in Italy with a plan to purchase one of the four cylinder racers that had been developed from the pre-war supercharged racer, a design that dated back to 1923. It had begun as the GRB, a combination of the initials of Gianini and Remor, the original designers, and financier Count Bonbartini, who owned an aircraft company in Rome. The GRB partnership invariably ran out of money and its assets were acquired by Bonmartini’s Compagnia Nazionale Aeronautica (CAN), who redesigned the machine and renamed it Rondine, after a type of bird noted for its rapid pace. Remor remained with the company, which also hired a gifted young engineer and talented rider, Piero Taruffi. The new Rondine was a revelation for the time; a double overhead camshaft, supercharged engine with water-cooled cylinders that pumped out well in excess of 80 horsepower. As well as winning several major races, Taruffi set a new world record for 500cc motorcycles of 244 km/h in 1935. Soon after, Bonmartini sold his company to the giant Caproni aeronautics concern in Milan who had no interest in the motorcycle division and began looking for a buyer.

Just down the road from Caproni’s headquarters was the company owned by Giuseppe Gilera, a successful rider and businessman who had started his motorcycle manufacturing company in 1909. By the mid-1930s, Gilera was a highly successful outfit which gained considerable success in mainly local reliability trials. Gilera himself had longed desired to move into the international racing scene, and jumped at the chance to take over the Rondine project, which included Remor and Taruffi, in 1936. Within a year the racing ‘four’ had been again redesigned, this time with a tubular frame in place of the pressed steel item, and with swinging arm rear suspension controlled by friction dampers. In the hands of Dorino Serafini, the new model took out the European Championship in 1939.

Following the ban on supercharging after World War II, the original water-cooled design was rendered obsolete, and a new air-cooled engine, also designed by Remor, was built for the 1947 season. With 55 horsepower at 8,500 rpm, and a race-ready weight of just 125 kg, the new Gilera was clearly going to be competitive. But it was not the instant success the factory had anticipated. Even the vastly experienced Nello Pagani was less than thrilled with the handling, and in fact opted to race his own single cylinder Gilera ‘Saturno’ in the numerous Italian round-the-houses events. Development continued on the four, and in the first year of the World Championships, 1949, Pagani scored two GP wins to finish runner-up behind Les Graham and his twin-cylinder AJS ‘”Porcupine”. At the end of the year however, Remor and several of the team personnel jumped ship to the rival MV Agusta factory, which soon had its own four-cylinder Grand Prix machine. Taruffi took over the Gilera team and with Umberto Masetti in the saddle, took out the 1950 500cc title.

And so, with the start of the1951 season fast approaching, Tony McAlpine, accompanied by his friend Ian Cameron, a staunch supporter of the sport from Maitland in NSW who had been instrumental in securing McAlpine’s appointment in Australia’s TT squad, arrived at the Gilera factory. Tony had a considerable wad of cash and a well-practiced argument (which included his Italian heritage) as to why he should be allowed to purchase a four-cylinder racer, but the reception was not exactly what he had in mind. Brash this may have been, but McAlpine was very well credentialled and clearly the most successful rider in his home country. Gilera however, were completely unmoved by either McAlpine’s cash or commitment, but were sufficiently impressed by his audacity that they agreed to sell him a single cylinder Sanremo Saturno racer. There was no time to argue. The TT was just months away and all the production Nortons were already spoken for, so Tony left with a receipt and went back to England, where he took up a part-time position with the Vincent HRD factory.

The 500cc Gilera Saturno had been around since 1939 as a sports road machine, but post- war was produced in limited numbers for the booming local racing scene. One of the premier events was the Ospedaletti Grand Prix at the seaside port of San Remo on the Ligurian Sea, where the annual street races drew huge holiday crowds. In its debut in 1947, the Gilera Saturno scored a handsome victory ridden by Carlo Bandirola, and the press dubbed the bike the Sanremo (sic) – a tag which stuck. Fittingly, Bandirola won again in 1948, with Sanremos ridden by Masetti, Colnago and Valdinoci victorious in the next three years. As well as the road racers, versions of the Saturno Sport were made for motocross and for the International Six Days Trial. For the 1953 season, two special works Saturnos were built with double overhead camshaft engines, reputedly producing 45 bhp at 8,000 rpm, but they made few appearances.

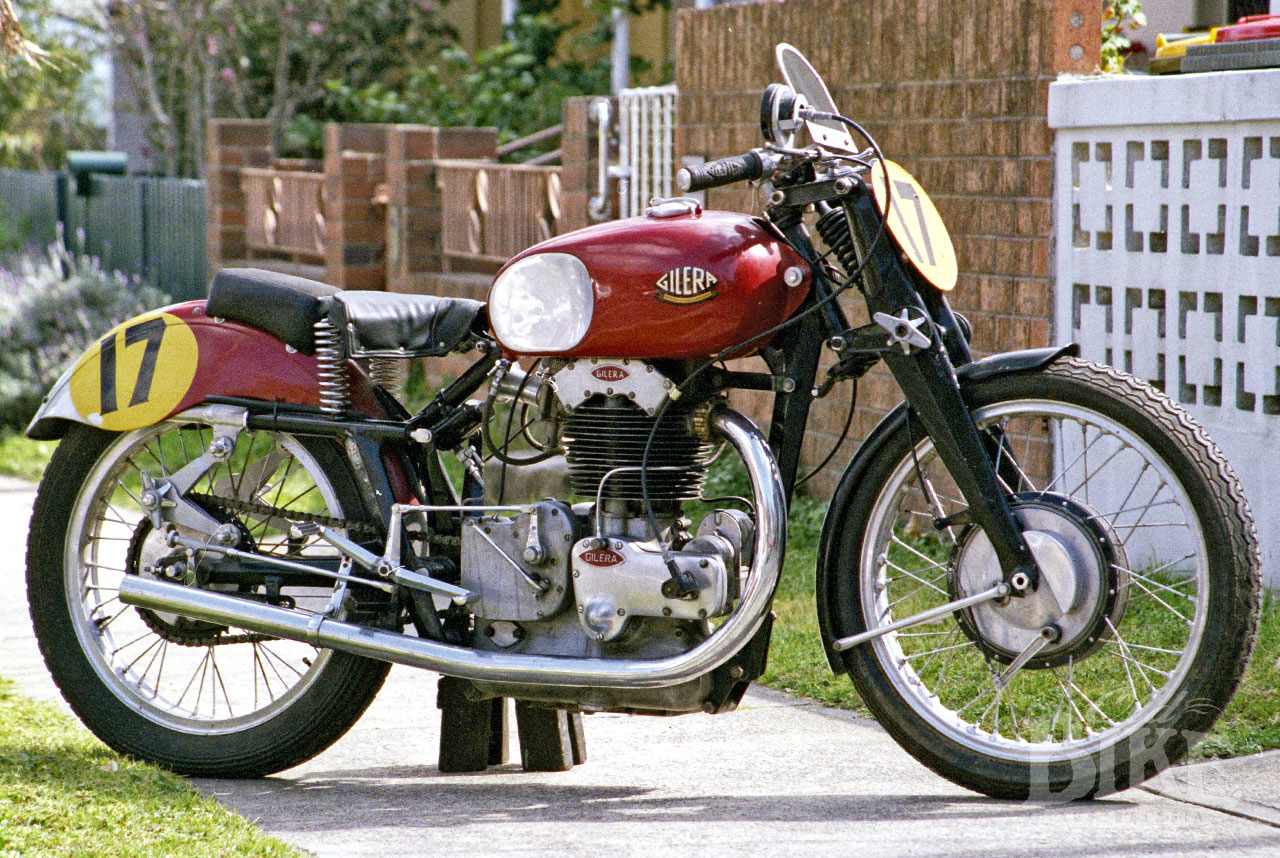

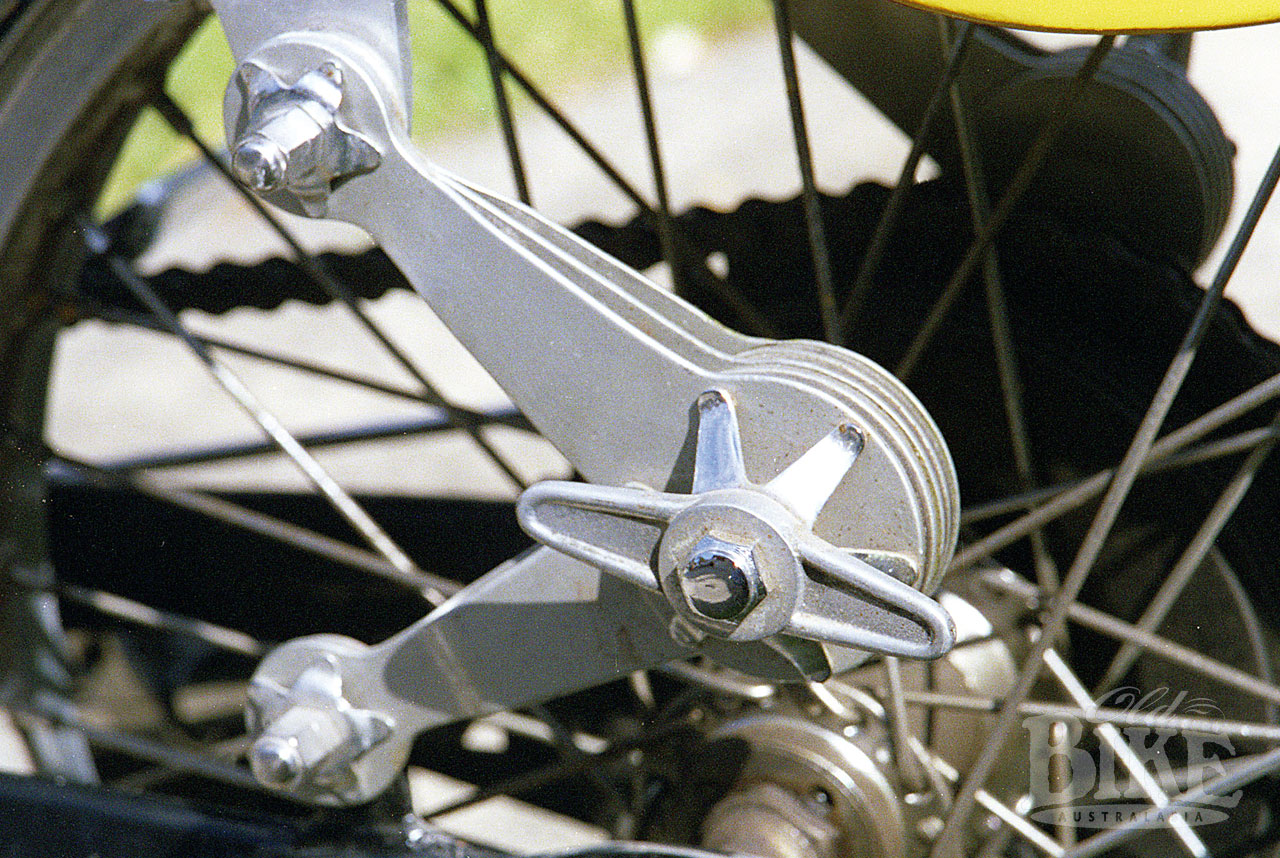

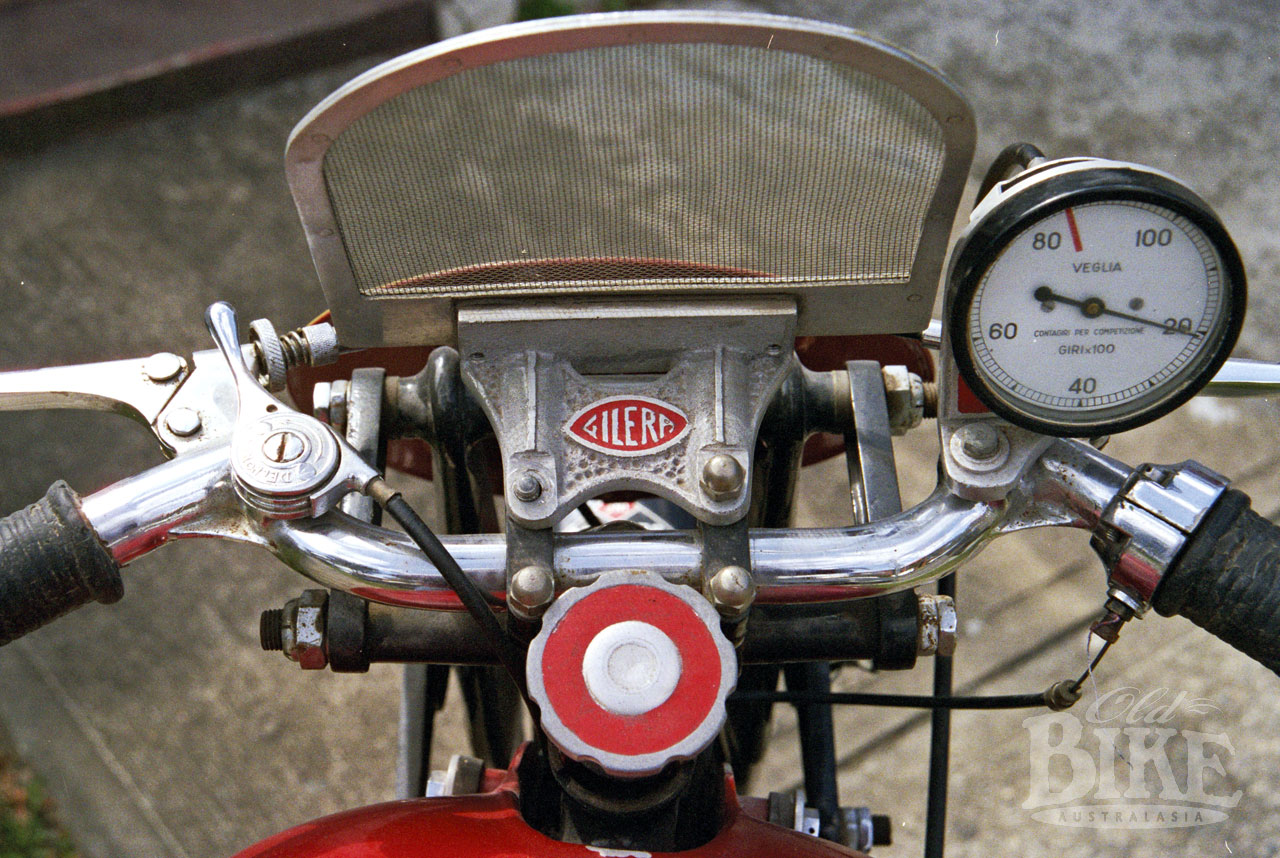

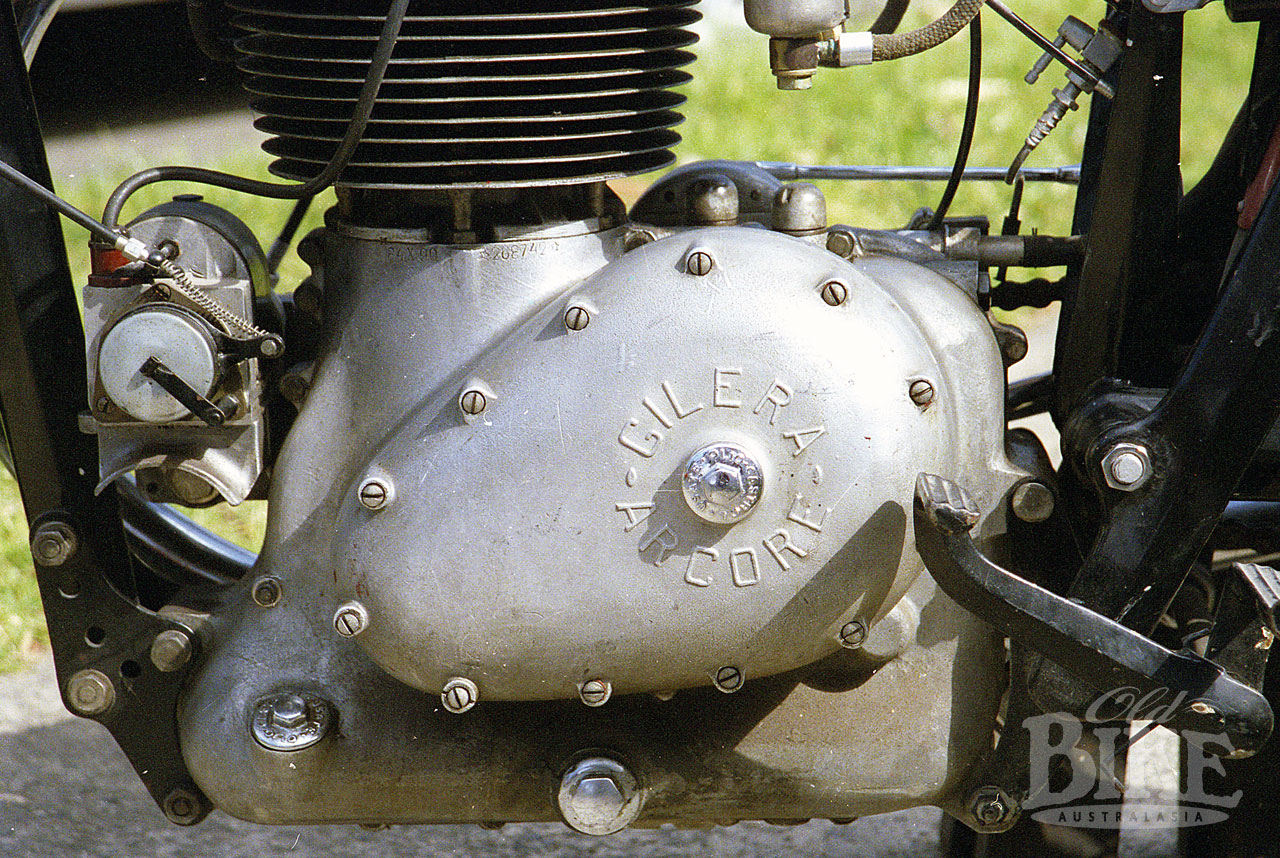

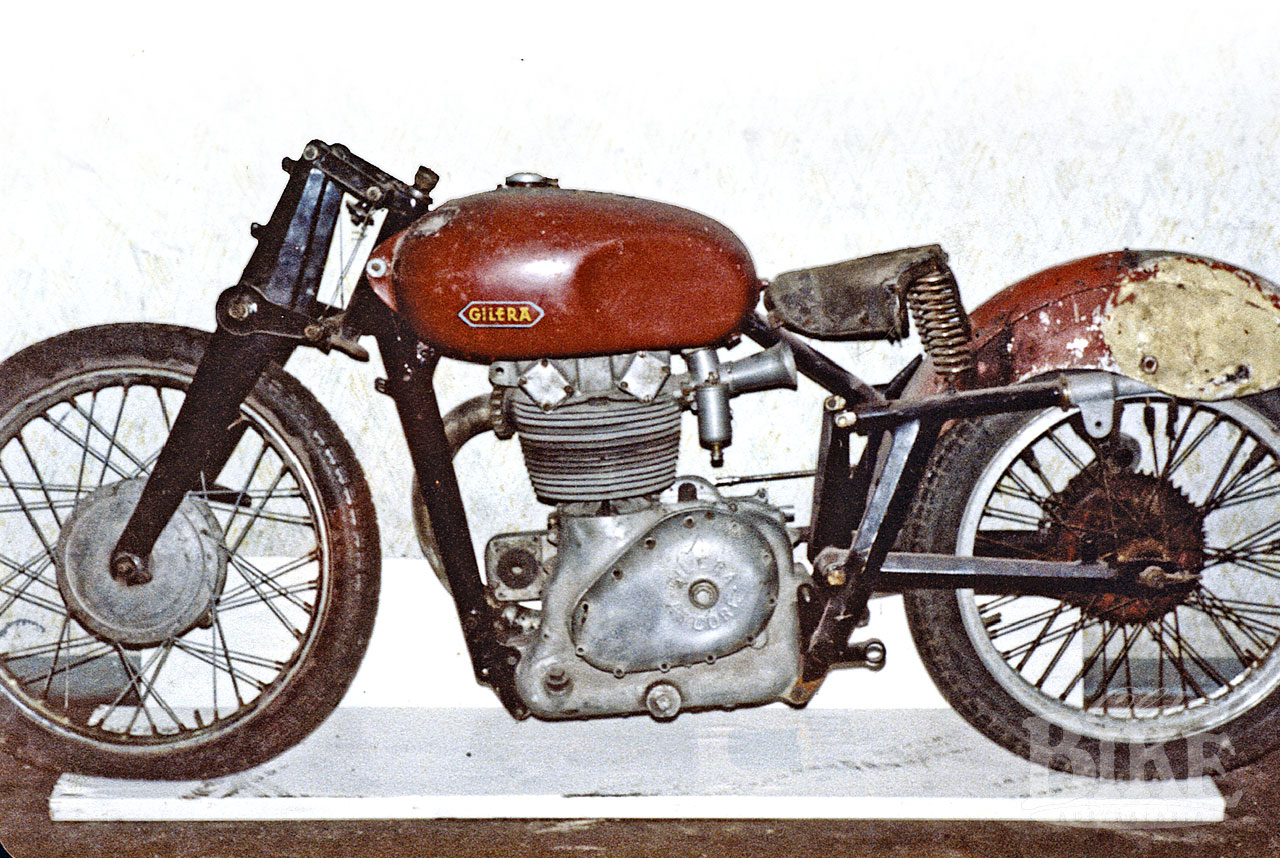

The 498cc all-alloy pushrod engine of the ‘production’ Saturno Sanremo, with its configuration of 84 x 90mm bore and stroke, was built in unit with a four-speed gearbox, with engine and transmission oil carried in an integrally-cast sump. Power output was quoted as 36 bhp and 6,000 rpm in 1947, breathing through a 32mm Dell’Orto carburettor, rising to 42 bhp and 6,500 rpm by the time the model run finished in 1957. The frame was a mixture of pressed steel and tubular components, with blade girder forks and Gilera’s own distinctive style of rear suspension. This used a swinging arm to the rear wheel, with a hollow parallel tube below the seat containing long coil springs. Dampening was controlled by hand-adjusted friction units. Wheels were 21-inch front and 20-inch rear. As the engine was progressively developed for more power (assisted by a larger 35mm carburettor), the chassis also came under review. By 1952, the girder forks had given way to telescopic units, while the frame was fully-tubular with conventional spring/damper units on the swinging arm.

McAlpine’s Gilera arrived on the Isle of Man by ship from Genoa only days before official practice started. The Sanremo had proved a nimble device around the small Italian tracks, with good acceleration and reasonable handling, but on the super-high gearing necessary for the 60 kilometre TT, it was not nearly so impressive. On his 350cc AJS 7R, McAlpine set quicker lap times than on the 500cc Gilera, the main problem being not so much than of outright speed but of lively handling from the distinctly pre-war chassis. In the 7-lap Junior TT, Tony brought the AJS home in an excellent 13th place at an average of 134.8 km/h, good enough to earn one of the prized First Class Replica trophies. In the Senior, held five days later, the Gilera broke a valve spring soon after the start and he struggled around the lap before retiring at the pits.

Back in England, McAlpine campaigned the Gilera without notable success, plagued by repeated valve failure, although he briefly led a star-studded field at Oliver’s Mount, Scarborough. At the end of the season it was shipped back to Australia, along with the Vincent Black Lightning that he had helped to build at the factory, and immediately put up for sale at Sydney dealers Burling & Simmons. With everyone clamouring for Manx Nortons the curious Italian machine took a while to sell, eventually finding a new owner in Keith Tolmie. It raced at Bathurst in 1953 and 1954 before being sold to Bruce Veitch and then to Italian immigrant Franco Boldi, who had come to Australia to work on the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Scheme. In its last Bathurst appearance in 1956, Boldi crashed the bike on Pit Straight after the rear suspension collapsed. The Gilera lay in the grubby workshop of Ryan & Honey in Sydney for many years, with bits gradually disappearing, including the rare 35mm carburettor. Eventually the remains were obtained by Sydney motorcycle historian Brian Greenfield, who began the complex task of restoring the old racer. It took many years and copious correspondence world-wide, plus a trip to Italy in 1978 to track down the missing parts, but eventually the Gilera was returned to its original state, right down to the 20-inch rear tyre, located in Perth, WA. Locating the flange-mounted 35mm SSF Dell’Orto was one of the hardest tasks but one eventually came to light after numerous letters to Gilera enthusiasts around the world.

Gilera marque specialist Raymond Anscoe believes the McAlpine Saturno is one of the very last of the original-specification production run, which numbered fewer than 100 over a seven-year period. Today, the Gilera’s appearance is best described ‘as-raced’, but complete and authentic down to very small details. It is a wonderful reminder of the colourful period of the early 1950s, when the odd Latin interloper would strive to get amongst the hoards of British machines – a red racer in a sea of silver and black.