Former top road racer Phil O’Brien has bent a lot of tubes for customers, so he thought he’d bend a few for himself. The result is a very special Velocette.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Dick Darby, Jim Scaysbrook

Sliding along the track at the ultra-fast Salzburgring in Austria with the field bearing down on him was not the way Phil O’Brien had intended to finish his European racing sojourn. Forty three years later, Phil recalls the day. “I had gone to Austria to deliver my G50 Matchless to its new owner, so to pick up some start money before I went back to Australia I decided to ride my 350 Aermacchi in the 500 race. I was in sixth place when the big end let go and it flicked me off. I thought, ‘That’s it, I’m dead’, but somehow everyone missed me. It was probably my fault; the big end had done two full seasons without being looked at.”

After the obligatory bashing around dirt short circuits on a MOV Velocette and later an Ariel, Phil’s road racing debut was made at the final meeting at the Gnoo Blas circuit at Orange in central western NSW in 1960. “I bought an ex-Tommy Phills MAC Velocette from Graham Tulk, which had the head modified to take coil springs instead of hairpins and was fitted with a full dustbin fairing. A few months later I raced it at Phillip Island and came second after a race-long dice with Brian Thomas on a Manx Norton. We smashed the C grade lap record and it was great to be congratulated by Tommy Phillis himself. Then I bought a Mk 8 KTT engine from Gaven Campbell and fitted that into a Nuge Smith frame – I sold that engine for fifty quid! Next came a 350 Manx that used to belong to Kevin Ferguson but I used to have a lot of problems with it wearing out cams. Allen Burt was selling a really nice late model 7R with a 5-speed Albion gear box, so I bought that and got second in the Junior B Grade at Bathurst in 1965 to Keo Madden. Myself and a few great friends – Ross Hannan, Brian Smith, Brian Coomber, Terry Dennehy, Jack Saunders, to name just a few – had dreams of the big time, and all had to work two and three jobs, as well as compete in as many meetings here as possible, which was made all the harder as there was very little racing in N.S.W. So there was many a Friday night overnight dash to Victoria or Queensland or even Adelaide. Race on the weekend then drive all night to be back at work on Monday morning for work – you could not afford to take any time off as every penny counted. There are endless stories of “hair raising” nightmare trips on bad roads and in even worse cars, the racing was the safest part of the weekend! Then a group of us decided to go overseas to the 1965 Manx Grand Prix; Brian Smith, Ross Hannan, Brian Coomber and me, but I backed out at the last minute to get married and buy a house, which in a way was a good thing financially.”

Buying a Triumph-engined Norton from Ross Hannan was to prove a turning point in Phil’s career. “It was just a road bike but (Speedway Sidecar star) Doug Tyerman did the engine and with a lot of help from Alan Stanfield we got it going pretty well. Alan was a genius; his father had a factory at Mascot that made Supreme mouse traps and Alan had a workshop there making mainly racing cars and equipment. He modified the frame on the Triumph, made the fuel tank and a hand-beaten aluminium fairing. It was a beautiful bike to ride.” The Triumph carried Phil to success at Oran Park and to third place in the Unlimited B Grade at the 1967 Bathurst meeting, behind Bill Horsman and Bill Pound. By 1968 finances had improved sufficiently to re-schedule the overseas trip, and Phil and wife Joy headed off to Europe where he bought 250 and 350 Aermacchis from the factory, ready for a full season on the continent. Although light and fairly quick, the handling of the Italian horizontal singles in standard trim left much to be desired. The Rickman brothers began making frames for the engine units about 1968, which were used to good effect by riders such as Alan Shepherd, but the basis of the design, with the engine support tubes passing over the top of the power unit, had come from the slightly eccentric rider/engineer Othmar ‘Marly’ Drixl in Switzerland. Drixil had built the frame with a Honda CB450 engine unit that Australian Terry Dennehy used quite successfully. “When I saw the Drixl chassis, I made a quick trip back to England and sold the two standard bikes to (British Aermacchi agent) Sid Lawton for a little profit, then began working for Marly learning the black art of frame making – the main point of the exercise being to get one for myself. You had to be very patient with Marly – he’d go down to the coffee shop and play pinball machines instead of working. It was a good experience, both in the gaining of the technical knowledge, but also getting to know about living and working in Italy, and meeting all sorts of legendary people like Jack Findlay, Daniele Fontana, Angelo Patoni, Alberto Pagani and many others.”

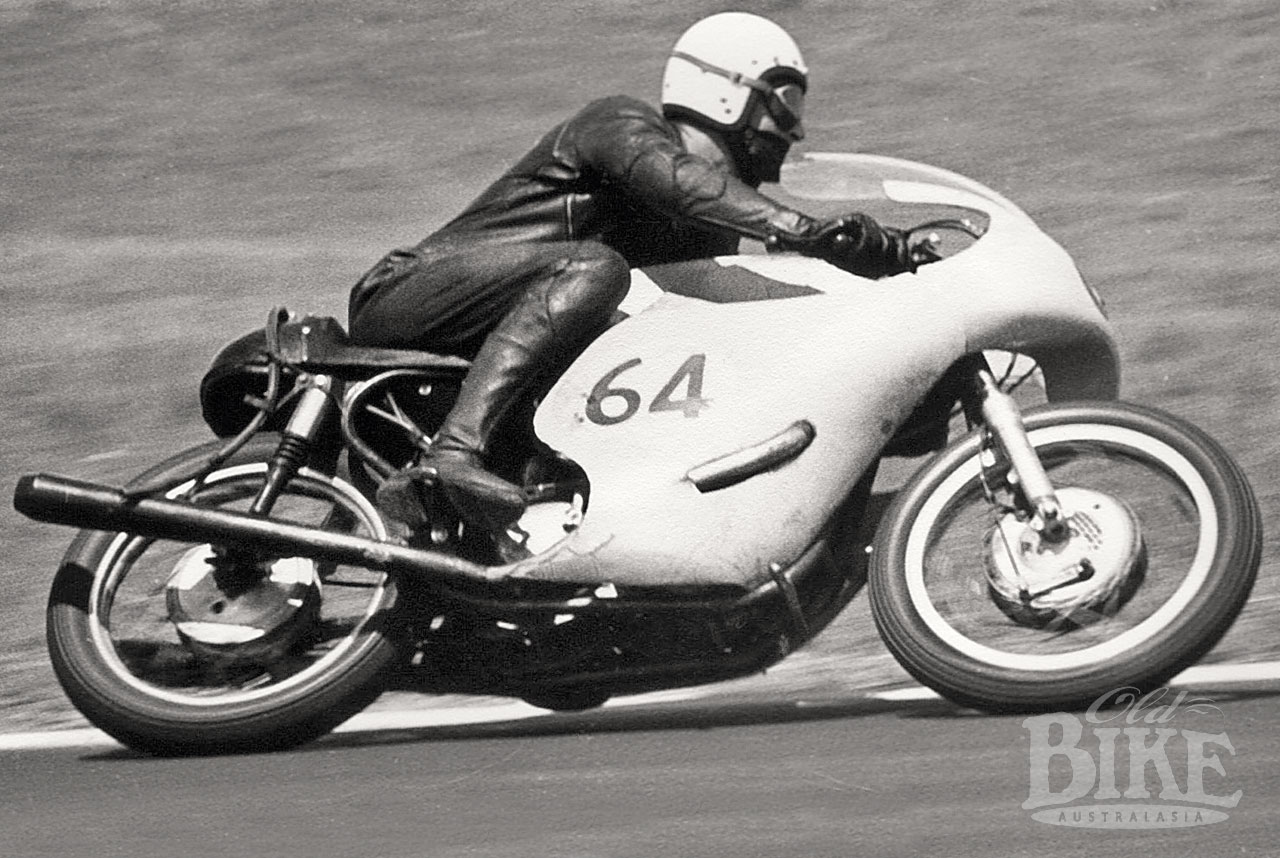

The Drixl Aermacchi 350 and the standard-framed 250 served him well enough to make a modest living in Europe. “I had a reasonably successful year but I could see the 500 class was the one to be in order to get starts so I sold the 250 to Jerry Lancaster and bought a really nice 6-speed G50 Matchless from (American rider) Marty Lunde for the 1969 season. On the G50 I finished 19th in the Senior TT, and at the Italian GP at Imola I worked my way up to 4th place, and passed Godfrey Nash around the outside which was the biggest thrill of my life because he was a bit of a legend. But the carburettor top was unscrewing itself and I tried to keep going but when you shut off it was no good and I thought ‘I’m going to kill myself here’ and I finished up 10th. I got 3rd in the non-championship Austrian GP and 6th in the East German GP, second and thirds in a lot of those international meetings they used to have. I came back with no broken bones so that was all good. The 2-stroke era was coming in and I’d never ridden a 2-stroke in my life and I didn’t know anything about them – I used to see guys perpetually putting cranks in them and picking themselves up off the road. The primary chains used to break on the Bultacos and jam, and I thought if I’m going to race these things I need to go home and learn all about them.”

Reality check

Back home in Sydney, racing had to take a back seat to re-establishing himself in business, raising a young family (son Grant had been born in April 1969, and building a house, but the bug was still there and Phil kept his hand in with his 350 Aermacchi, which was useful on tighter tacks like Hume Weir but outgunned by the Yamahas on the faster circuits. Eventually he did the logical thing and bought a TZ350 Yamaha.” I did a bit of racing when I got home, got 3rd at Bathurst in the Junior B Grade in 1976 won by Graeme McGregor, Rick Perry was second. My last ride was at Calder just short of my 50th birthday. I was on a 125 Honda on a freezing cold June weekend – I was going to win that race – but it nipped up and I crashed – five screws in my ankle and other broken bones. So for years I didn’t do anything, although I owned an Mk II RG500 which was a really nice bike that I paid $2,500 for and I had a couple of rides on it. Then the Assen reunion (Centennial Classic in 1998) came up so I rebuilt it to absolutely immaculate but 5 weeks before the event – just before we had to get it into the container – I took it to Oran Park to run it in with brand new Metzeler tyres on it and on the first lap I thought I’d just check the front brake and it went straight away from me – I wasn’t even going fast but the tyres were still waxy from the moulds – and I broke six ribs and my shoulder. By this time I was 60-odd but I rode it anyhow at Assen, all strapped up and I had to get people to push me, it really took the shine off it. I bought the RG back and had a few rides at club days at Oran Park. Then I wanted to buy into a business so I thought I’d sell it and I put an ad in an English magazine. A guy contacted me who had houses in Thailand, Singapore, and London; he paid for it and then didn’t contact me for six months but eventually he rang and said “you’d better send that bike I suppose’.”

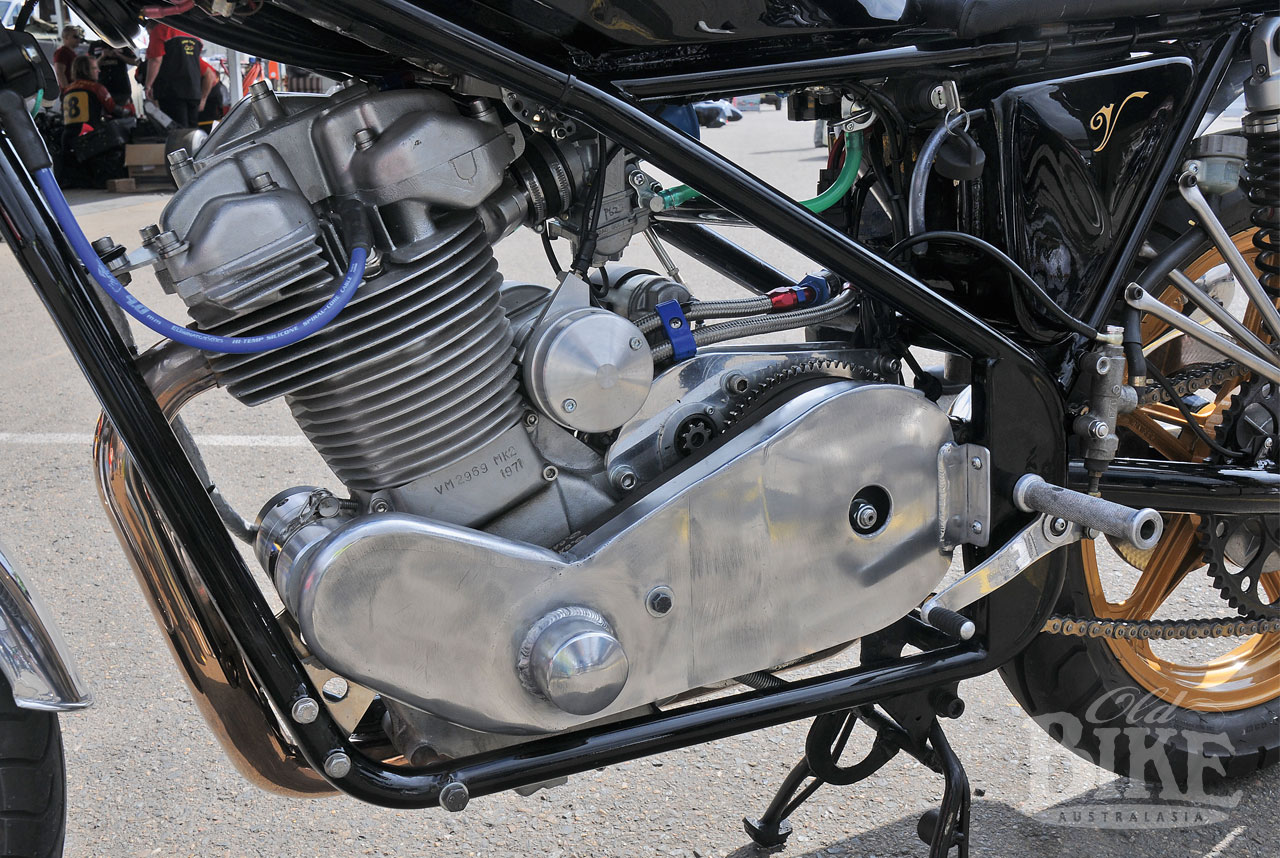

Concentrating on his tube bending business largely kept Phil away from the racing scene thereafter, but prior to this he had built a replica Seeley frame for a customer. “A wild Irishman named Les Thompson had a G50 Matchless engine in a Seeley frame that he was racing at Amaroo Park and Oran Park and he asked me to make a copy of the frame so he could build a second bike, which he also raced. Then he came back to me about ten years ago and asked me to make him another Seeley frame, which I three-quarters finished, but he never came back and the frame just sat there in the workshop. So about five years ago I thought, ‘Oh well, I’ve got a Velocette engine and I’d always fancied doing something like this so I started to work on building it up. I had to chop a few things around to convert it from G50 acceptance to Velocette.”

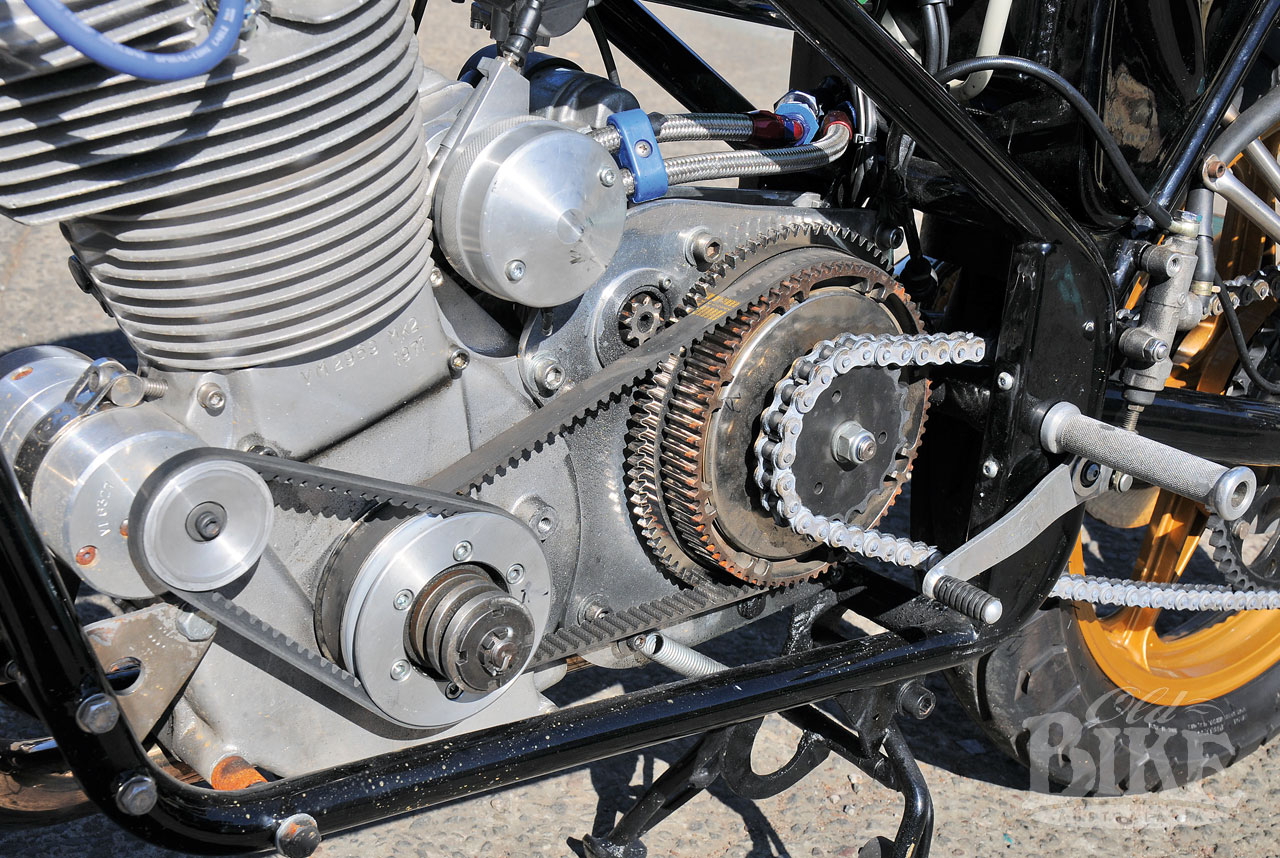

Substituting the Velocette engine for the OHC G50 was not as straightforward as it may seem. “Chris Dowd did the whole engine, including modifications like straightening the exhaust port up, because the Velo exhaust port was pointing straight at one of the front down tubes – the G50 port comes out centrally and the pipe runs between the down tubes. It was a standard Venom engine, but now it has a Carillo rod and a BMW barrel that takes it out to 600 cc, Nikasil bore with a Wiseco flat-top piston. The combustion chamber in the cylinder head has been welded up to accept the flat-top piston. We haven’t altered the valve angles but it has a bathtub-shaped combustion chamber which gives plenty of squish-effect. Chris put a bit of a lump on the piston to bring the compression up to about 9.5:1. Knowing how cantankerous to start Velos can be I wanted to put a starter motor on it, but I didn’t want to use one that goes where the generator usually sits, although I’ve used the French Altron 12 volt alternator in that space. We thought we’d approach it differently and I had a gear made locally to fit in the back of the clutch and used a Toyota starter motor. I would have liked a smaller Japanese motor but they run through a train of reduction gears and I thought it might have been too big an ask to turn this engine over. I disconnected the valve lifter – it is unnecessary because the starter always manages to turn the motor over compression OK. It has a belt primary drive kit that I bought in America, Kevlar plates in the clutch, 41 mm flat-slide carb, electronic ignition that Chris made up. It’s a Dyna ignition that utilizes battery power. We’ve had a few little issues with that, I burnt a coil out recently – it was one made for a multi-cylinder engine with a shorter build-up time between firing and of course this one only fires once to every four rotations so it was building up too much energy in the coil and burnt it out. You just learn these things, but we now know we had to get a single cylinder coil.”

“Most of the rest I made; the frame, the exhaust pipe, oil tank and I cut down a Ducati fuel tank that I got off Ian Gowlanloch – I cut 100 mm out of the centre and moved the filler cap. The forks are from a 250 Aprilla with Ducati wheels from a Pantah. I’ve fitted a few engines in frames for guys over the years, chopped and changed things, so making the frame wasn’t a complete step in the dark. I couldn’t have done the engine without Chris Dowd, and Alan Mitchell (Alan Mitchell Motorcycles at Kirawee, Sydney) did the electrics – he is a genius on that side of things – Greg Reardon did the painting and Tony Hatton has been a big help too. We’re going to dyno it at Peter Campbell’s place once we sort the mixture out. It’s standard stroke but well over square because of the bore and it really pulls.”

“I suppose it took me about five years, which is about how long Chris took to do the motor so there was no race. I just had to fit it in with my other work but now and again I would get a bit of a spurt on and do a bit more. I realised time was catching up with me – I am 74 this year – so I put the pressure on Chris and that must have struck a sympathetic chord because he did get it finished. People always ask me how long it took and it sounds a bit funny to say ten years but it was in fits and starts, from having the frame to gathering bits and pieces here and there.”

Phil admits the Seeley-Velo is not quite there yet, a persistent flat-spot defying all attempts to cure so far, and there have been other niggling teething troubles like a broken clutch cable that curtailed our first photographic session, but he’s confident all will come right, and he’s delighted at how the machine rides. Visually, it is a motorcycle that stops people in their tracks. Even while we were chatting in between runs to photograph the Velo in action, an elderly gentleman who was walking his dog in the reserve beside the Woronora River south of Sydney stood mesmerised, carefully running his eye over the svelte creation. “I thought I knew everything about Velocettes,” he said, ”but I’ve never seen one of these.”

“Oh yes”, replied Phil dryly. “They only made one.”