From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 86 – first published in 2020.

Words and photos: Geoffrey Ellis • Historic photos: Rob Lewis, Earl Brooks, Ray Stone.

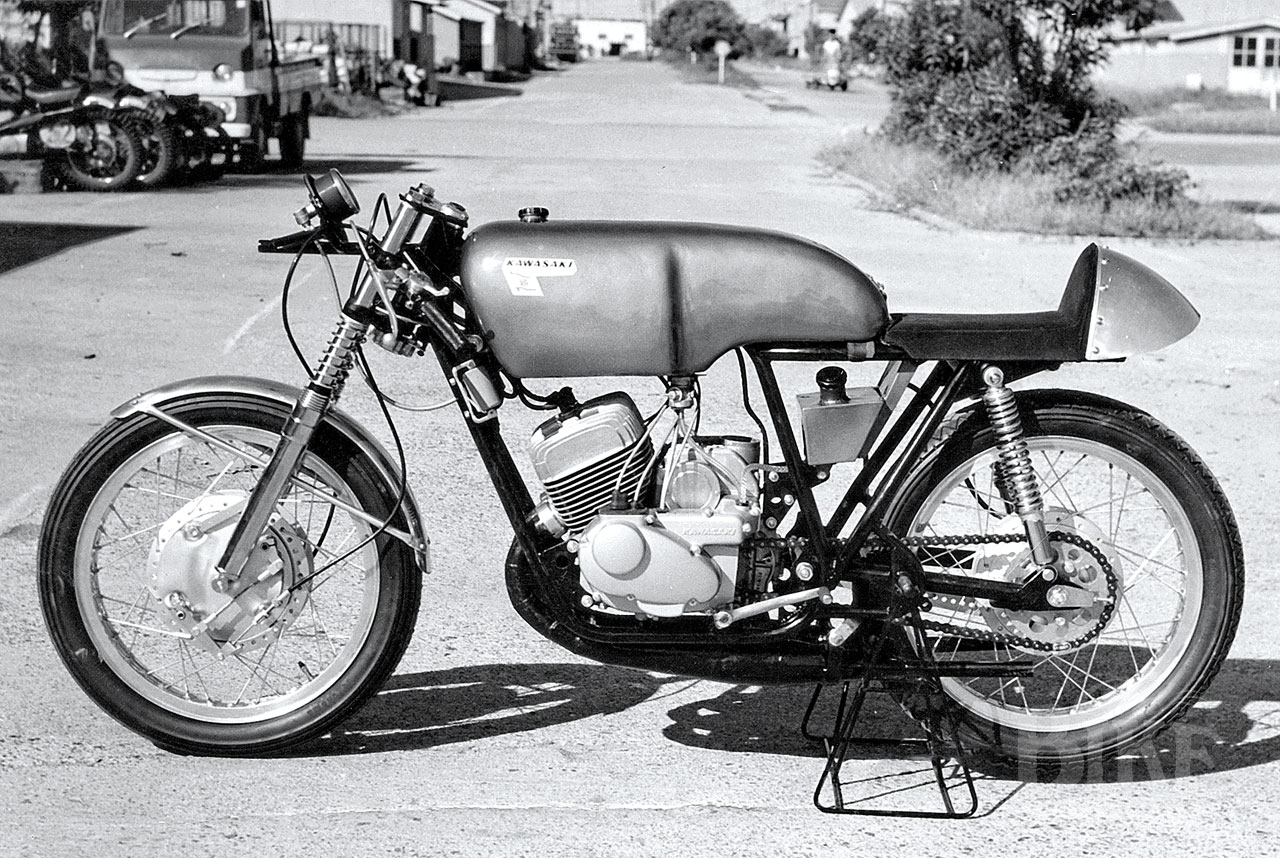

Arguably the most aesthetically attractive Japanese 250cc over-the-counter racer ever produced, the Kawasaki A1R’s sole purpose was to impress the world markets with looks and performance. Loosely based on the 1967 250cc A1 Samurai street bike, the A1R was Kawasaki’s first attempt to produce a racing motorcycle that could win national titles and lure the buying public.

In 1958 a Japanese government study identified the USA as the prime motorcycle market having far more potential than Europe/UK, with seven times less motorcycle ownership. Kawasaki entered the market well after the other Japanese motorcycle manufacturers but the USA motorcycle sales boom was just beginning so Kawasaki concentrated their effort and established a USA marketing/research branch. In the 1960s the 250cc class was full of bikes bristling with innovation and technology as the Japanese makers’ performance road models were 250cc.

Racing had grown in popularity in the US and over-the-counter road bike-based racing motorcycles complied with US racing regulations, so Kawasaki developed the 250cc A1 Samurai road model into the A1R racing model. These road-based racing motorcycles were heavily subsidised by the manufacturers, as race bikes were advertisements for the money-making road bikes and more importantly if twenty race bikes were sold, the company effectively gained twenty development teams at no cost as owners would continually improve the machine to obtain the winning edge; a strategy Yamaha had exploited to great advantage.

Economics of some form must always prevail so instead of making a handful of specials at high cost, 200 A1Rs were scheduled to be produced over 2 years (1967 and 1968). Two prototypes were built using very standard looking A1 engines and raced in the USA with major engine modifications being made before sales commenced. Being an unknown made it was impossible to sell 200 to the target USA market so Kawasaki took an unusual step and released the A1R simultaneously to countries having Kawasaki dealers and an established racing scene which included Australia. Actual quantity sold is not known as A1R’s were more expensive than others and Yamaha had already established a winning reputation.

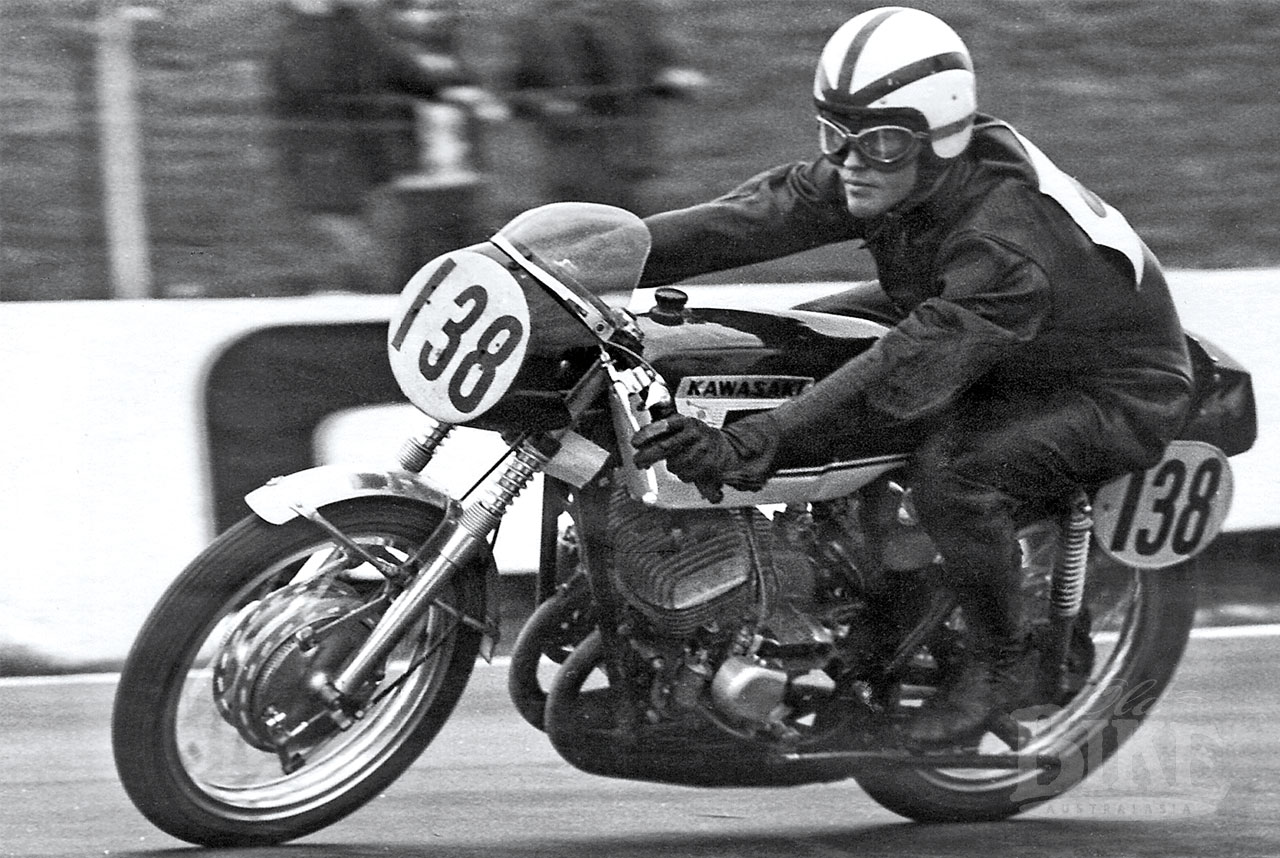

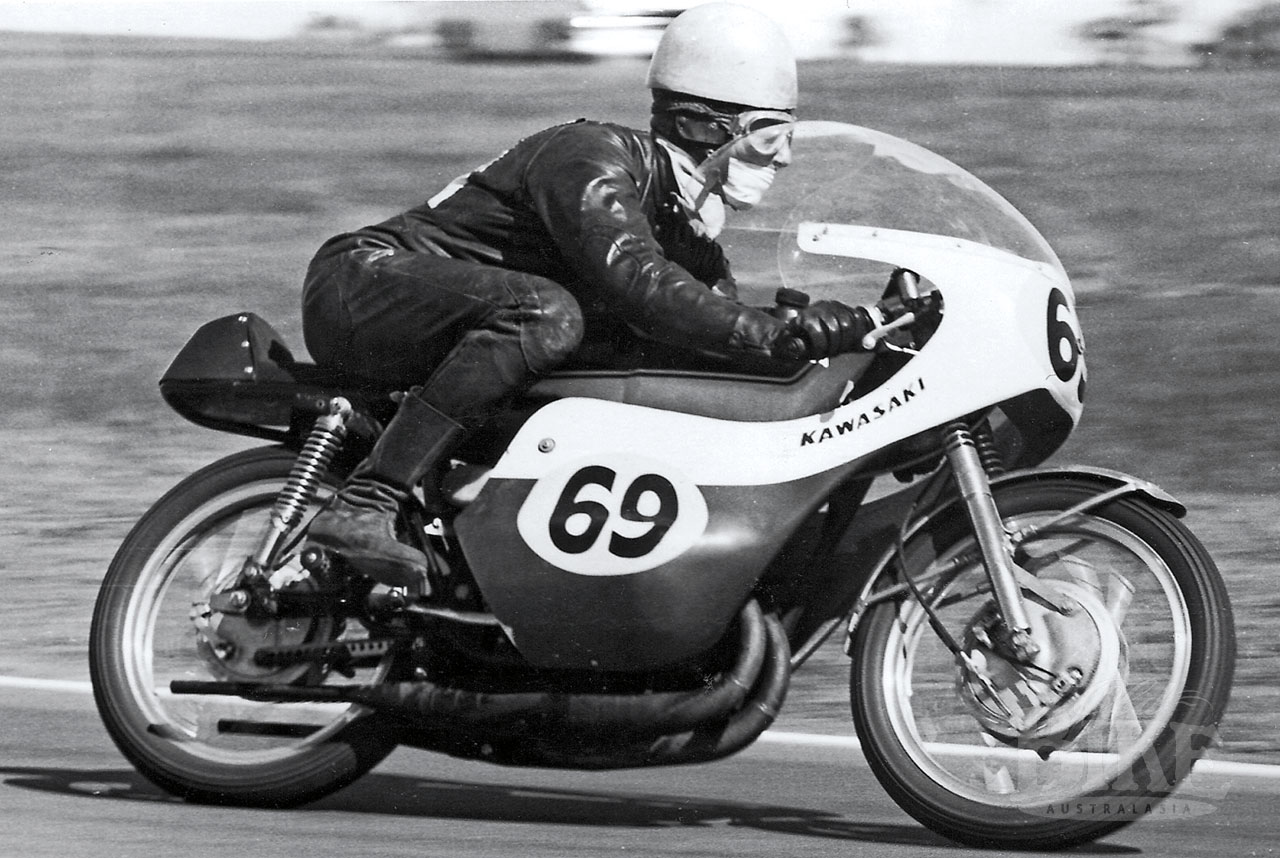

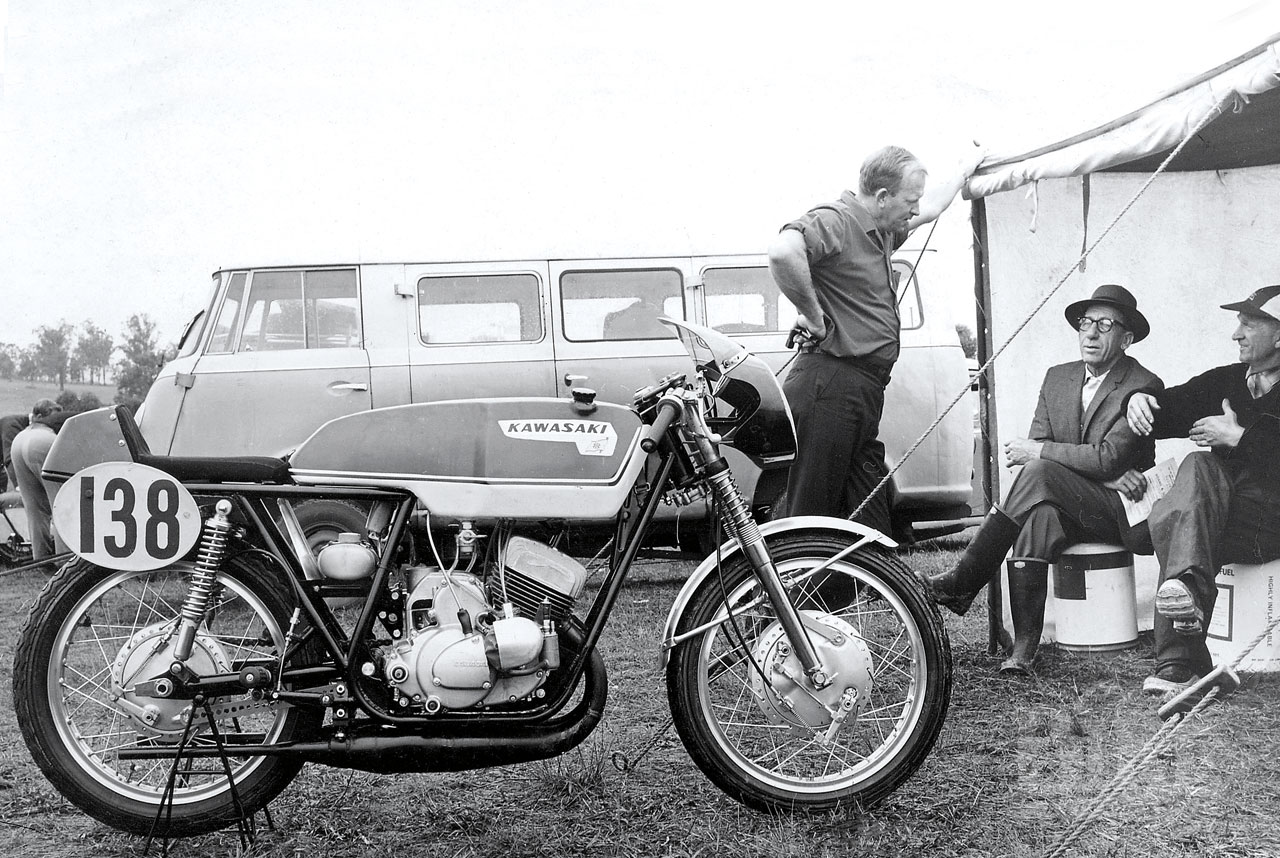

There was no doubt that the A1R looked the part with a double-sided twin leading shoe front brake, disc valve two-stroke engine with remote float bowl carburettors protruding from its sides, expansion chambers and an adorable design and paint scheme. Its appearance gave the impression that it was the real deal and when Victorian Dick Reid started winning races by a comfortable margin the A1R and the Kawasaki brand gained a lot of credibility in Australia.

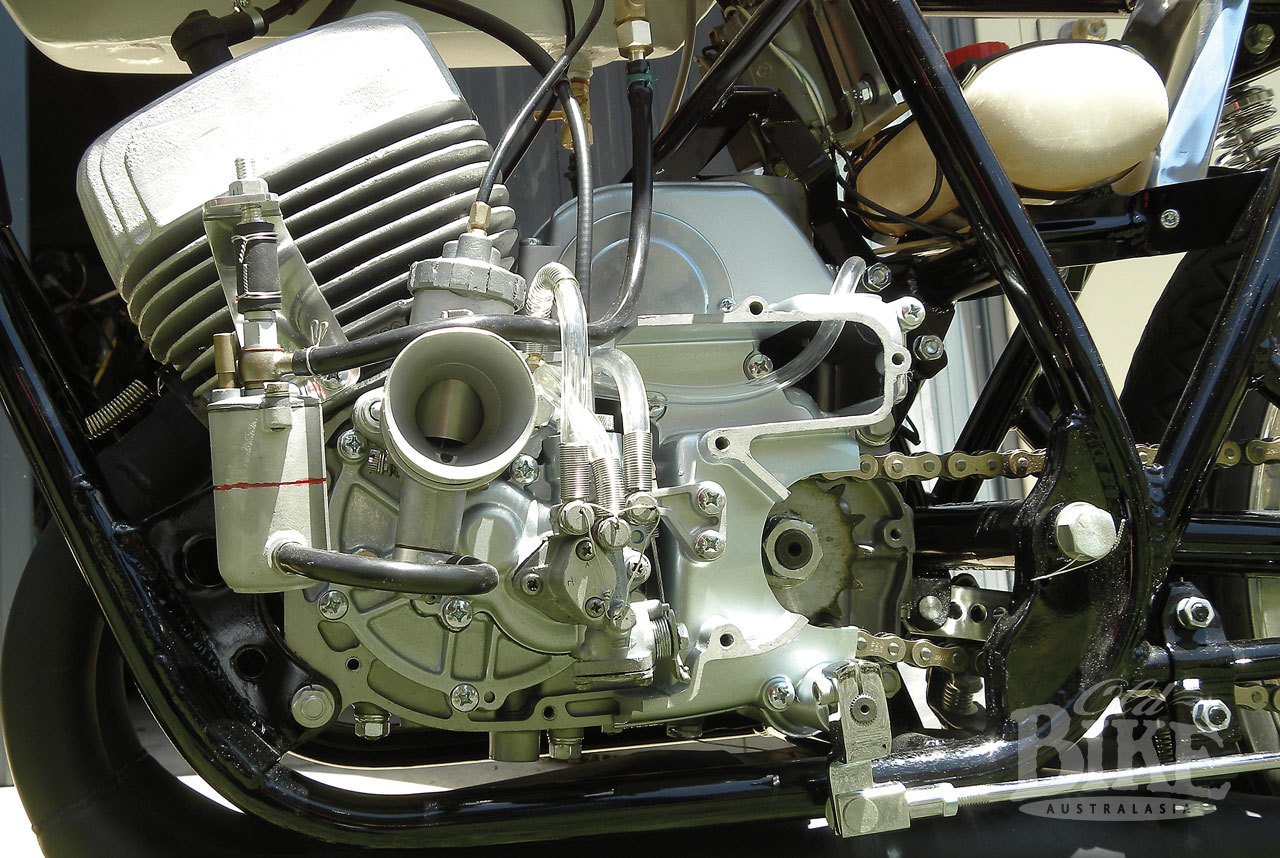

Whilst promoted as a hotted-up A1 Samurai street bike to portray Kawasaki’s performance aspect, in reality there were many differences. The primitive Gestetner-copied owner’s manual was primarily devoted to the differences between it and the road model but the basic concept was a Samurai twin cylinder, disc valve induction two-stroke of 53mm bore x 56mm stroke displacing 247cc. Disc valve induction produced more power because the inlet port is opened and closed by a cut-out in a disc on the end of the crankshaft with the opening and closing of the port being independent of each other. Not having the inlet port in the cylinder created space which was used for an additional scavenge port assisting in expelling burnt gas to allow more new uncontaminated fuel charge to enter. Superbly aiding the disc valves were the A1R’s advanced design exhaust expansion chambers being short fat and tucked in with stated power of 40+bhp at 9,500rpm; the A1 was 31 at 8,000.

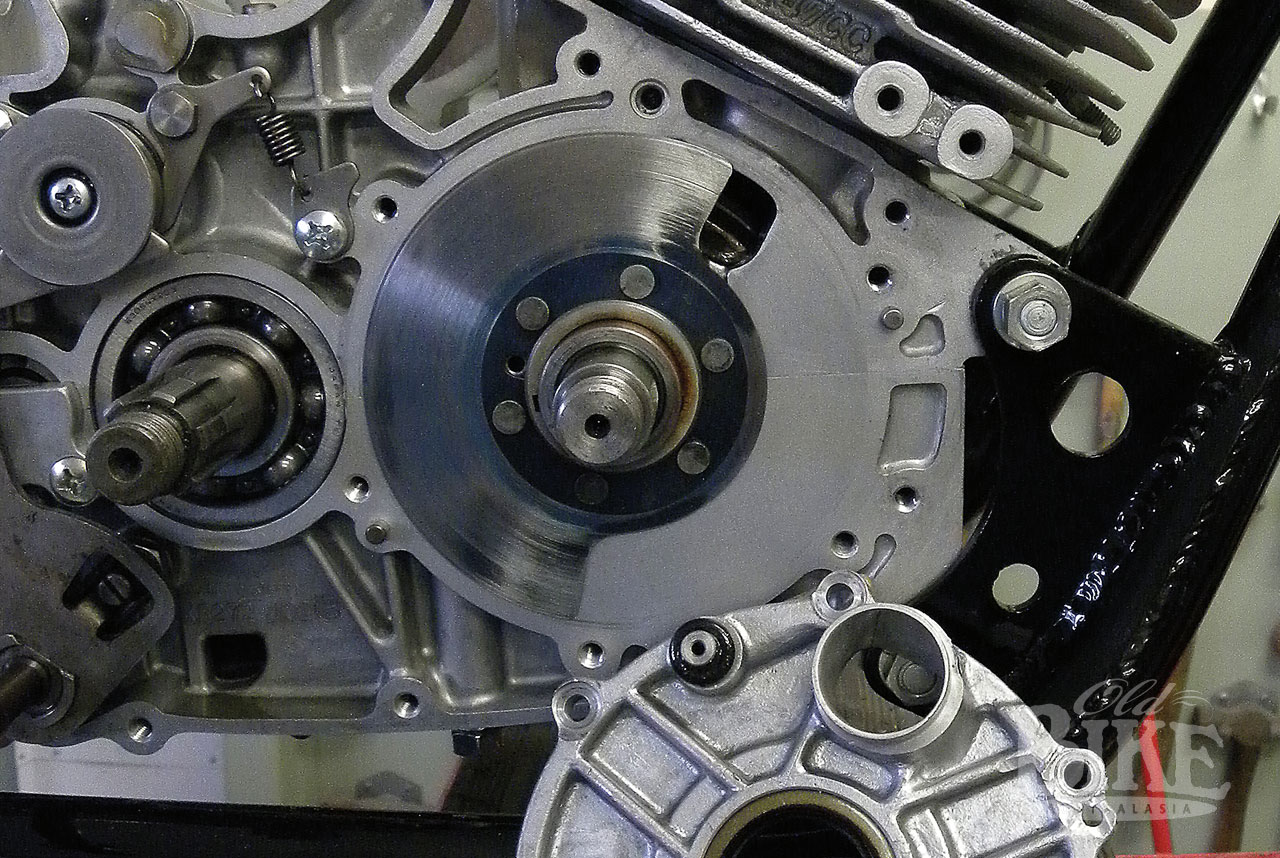

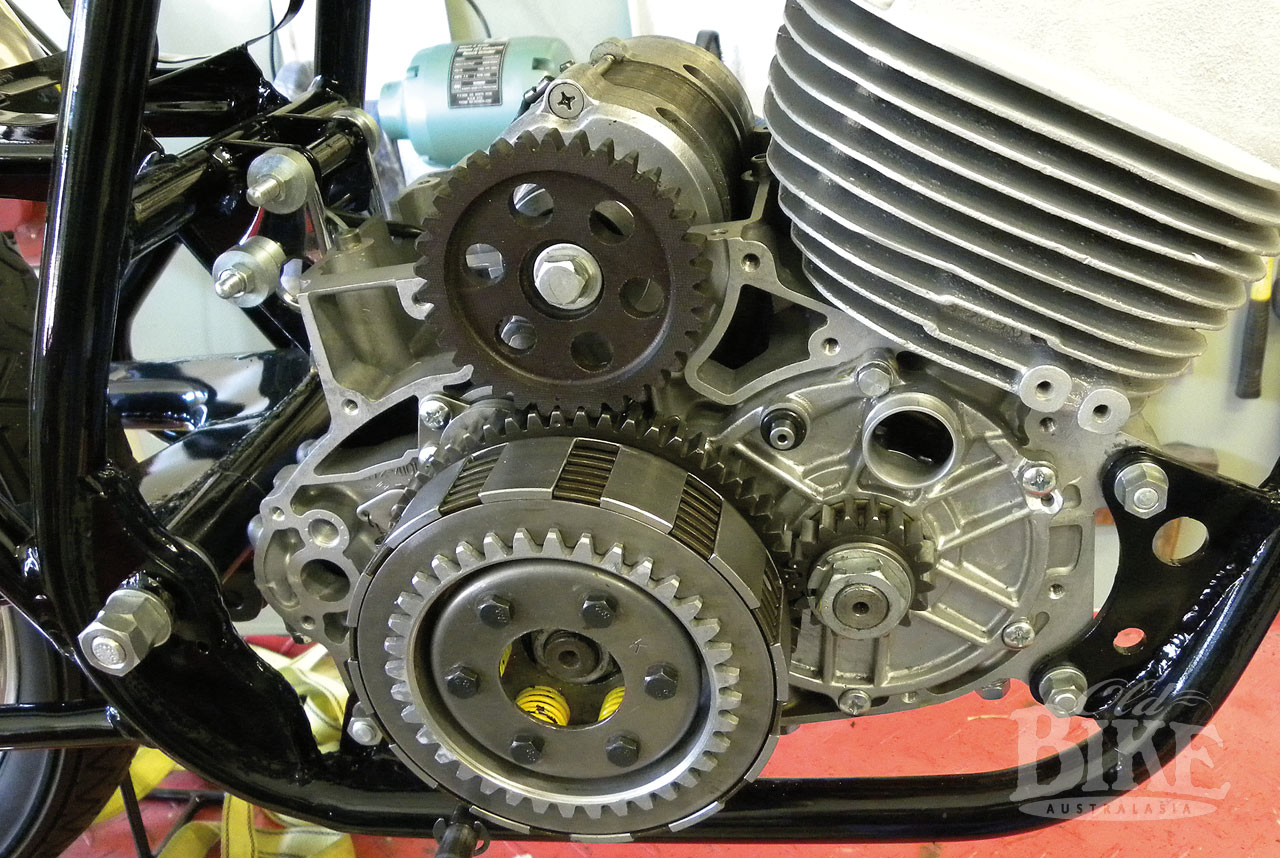

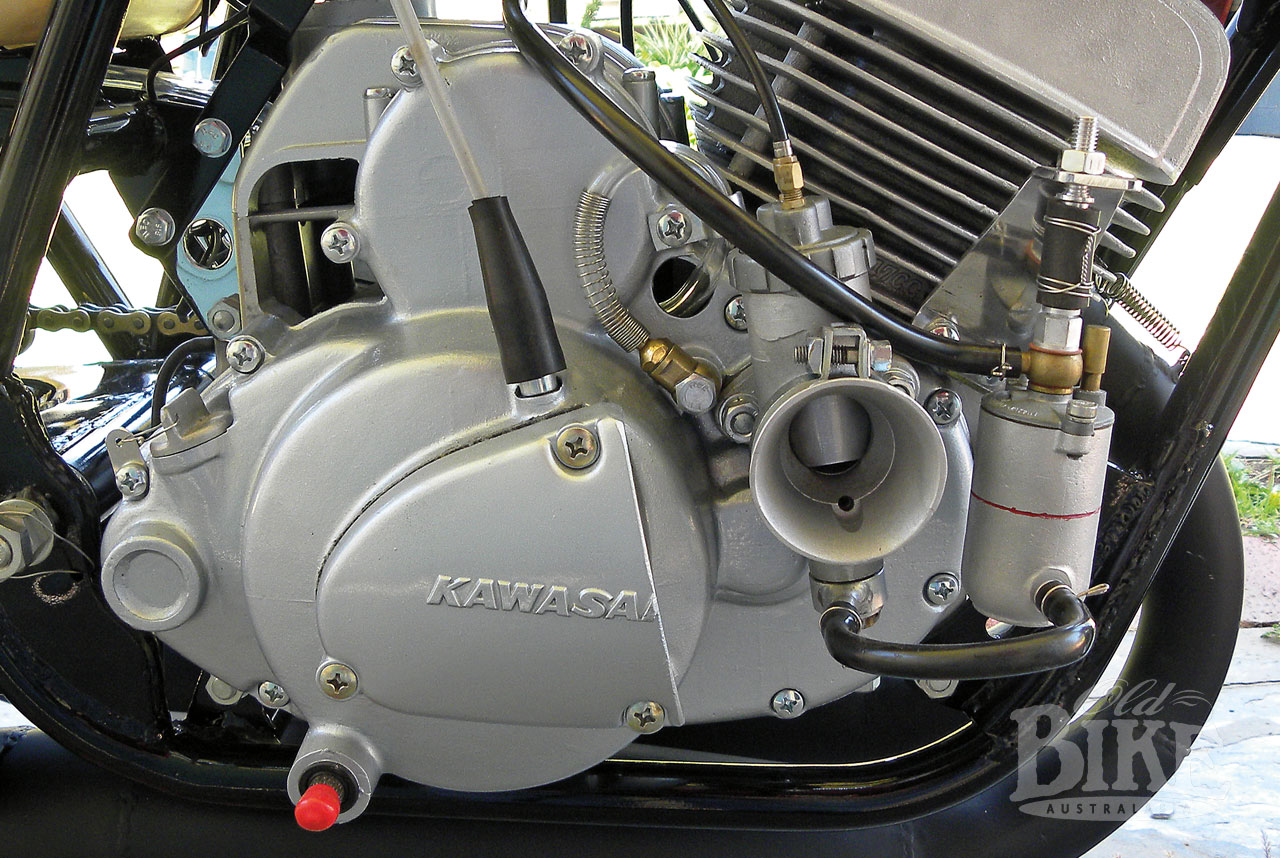

Analysis of the A1R engine to the A1 shows that the cylinders, although being iron liners cast in to aluminium cylinders as per the A1, had a different profile, iron liner and aluminium materials plus race-orientated ports. The heads had a different profile and combustion chamber shape allowing racing spark plugs to be used. Spigots on the cylinders allowed remote float bowl brackets to be attached. The A1 extended threaded exhaust ports were gone and a set of exhaust stubs attached which were grooved to allow the expansion chamber to slip into and then held in place with springs. Pistons were light weight with thin 1mm wide rings. Although the crankcases looked the same as the A1 there were machining differences with the crankshaft slightly different and more accurate. On the end of the crankshaft were 0.5mm steel disc valves instead of the A1’s 3.5mm fibre discs with a different cut-away. Modified cast disc covers were required to allow the carburettors to be bolted on instead of slip-on requiring a different outer case on the clutch side. To reduce friction the primary drive was by spur gears whereas the street bike used helical gears to reduce noise. Unlike the A1 the magneto was driven directly from the A1R clutch gear. An extra set of plates was fitted to the A1R clutch and stronger springs used.

As the A1R was a race bike a five speed close ratio gearbox was standard with only two cogs being from the street bike and although a kick-start was fitted the mechanism was different – with most being removed as unnecessary weight. This was the era where racing motorcycles were push started. On top of the gear box was the Kokusan magneto which was covered by one of the few A1 parts being the air duct and air-cleaner mounting casting which was retained because the sides clamp the magneto in place. Tuners of the day would cut the casting away to only leave the side clamps as the full cover restricts the space which also has the fairing mounts and ignition coils. Although pre-mix fuel/oil was the main lubrication, the Samurai “Superlube” oil pump was retained but only partly worked. On the street version, “Superlube” squirted oil into the motor via a jet mounted between the carburettor and the inlet port plus via another oil passage into the main bearing before mixing with fuel. The volume of oil injected was metered by the throttle opening. As the inlet stubs were not part of the A1R castings the oil jets could not be fitted but the additional oil passage to the main bearing and oil pump was retained with a fixed pump setting. Oil was contained in a plastic oval shaped container located between the motor and rear wheel. Tuners did not like this arrangement as the oil to fuel ratio varied with the throttle opening and some tuners discarded the pump and oil bottle. The A1 engine left-hand cover was pared back and a large semi circular cut-out allowed easy sprocket access but tuners severely modified this also.

Where the A1 was fitted with Mikuni designed 22mm integral float bowl mixing chamber carburettors, i.e. what we consider as standard carburettors, the A1R was fitted with 26mm English Amal licensed M26R remote float bowl units manufactured by Mikuni. Mikuni had a technology agreement with Amal so when Mikuni wanted a racing carburettor Amal would provide some obsolete design such as the A1R carburettor or in the case of Yamaha the very basic out-dated 276 type. Ironically Mikuni’s knowledge in producing integral carburettors outstripped Amal’s and many owners changed to integral Mikunis as fuel frothing was not an issue, and discarded the antiquated Amal and bowl. Mikuni’s remote float bowl was virtually standard although each manufacturer wanted a unique design so fuel inlets and outlets were changed. To set the float bowl at the right height the rider sat on the bike and a mechanic lined up the red line on the float bowl with a red dot on the mixing chamber. A choke was fitted but generally was discarded as a cold motor was easily started by “tickling” the float bowls. Kawasaki fitted rear opening vent covers over the carburettor intake which were possibly fitted to stop debris entering the motor but were removed by owners.

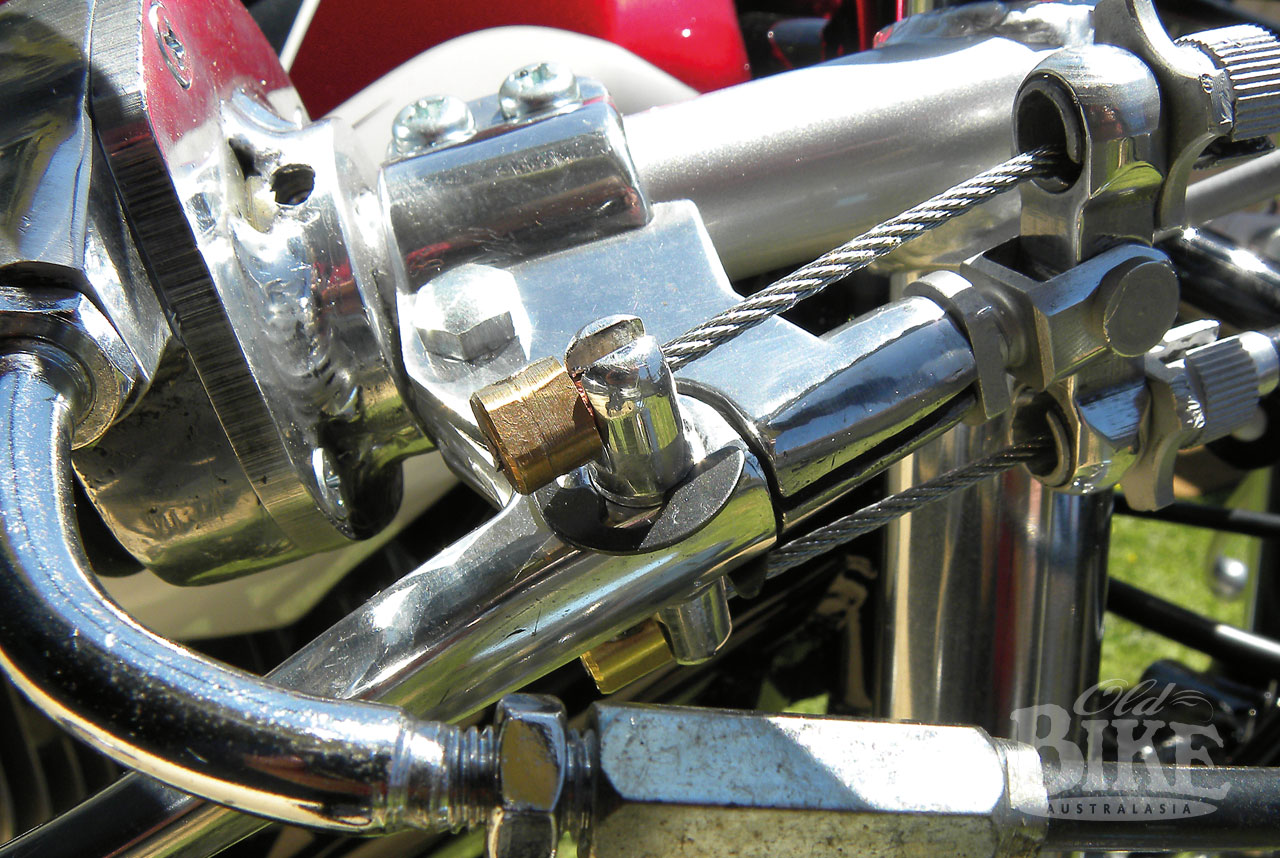

The frame was virtually the A1 frame with some small strengthening modifications but the swinging arm had large pressings welded in adding more rigidity. In a 1968 Cycle Guide test the writer said “In the handling department I feel that the A1R is better than any other production racing machine with the exception of the Norton Manx which is admittedly the finest handling bike ever built.” A stand came with the A1R which was unusual for the time being used in conjunction with two small spigots welded to the swinging arm just by the rear axle. At that time many riders also raced larger British machines with the gear lever and foot brake on the opposite sides to the A1R, so Kawasaki built the motor with the gear change shaft protruding at either side (A1 style) and fitted all necessary brackets to both sides of the frame. With the link arm on the gear lever being re-bolted to the lever, the foot controls could easily be swapped. Suspension was basically A1 Samurai with stronger springs and minus the covers. A unique and advanced feature was a hydraulic rotary steering damper fitted to the front fork lower triple clamp. Dry weight was a competitive 109kg.

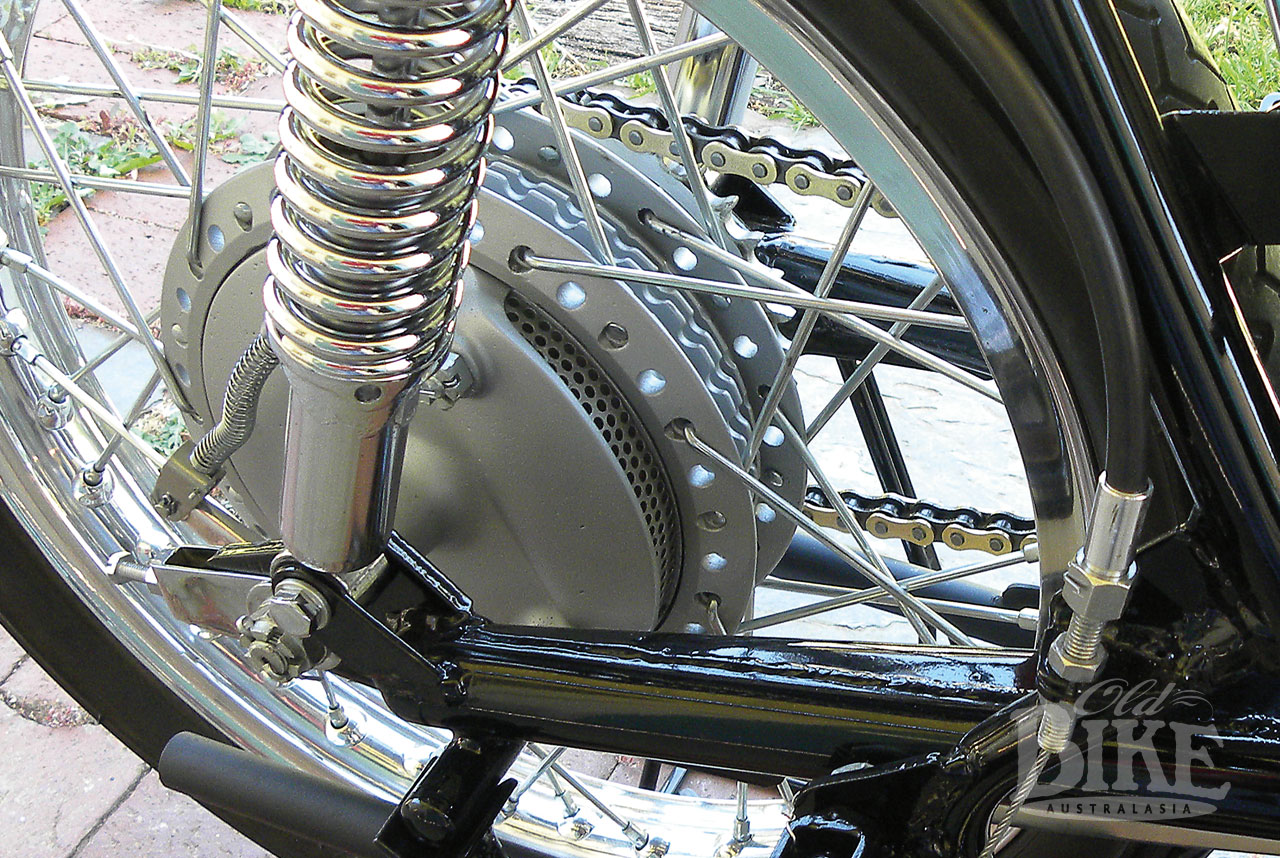

Wheels were a stand-out item with the 200mm double sided twin leading shoe race oriented front brake having air scoops to let cool air in and vents in the centre of the hub to let hot air out. Similar brakes were very rare at the time but when track tested by Cycle Guide brake fade occurred. Rear brake was similar but only single sided and single leading shoe. Flanged aluminium rims were narrow WM1 fitted with 2.75 x 18 front and 3.00 x18 rear Yokohama racing tyres which are those on the featured bike. Yokohama was Japan’s first tyre manufacturer (1917) and the first Japanese manufacturer of motorcycle racing tyres which were standard fitment on Kawasaki and Yamaha over-the-counter racers, performing far better than history has recorded.

An aircraft grade aluminium petrol tank was held in place by three rubber straps and had an unusually long filler tube extending to near the bottom of the tank with the owner’s manual correctly pointing out not to drop any object into the tank as the object cannot be removed. Of questionable design was the seat as the base was thin aluminium which fatigued, cracked and fell apart easily but the rear hump, which did nothing, was of reasonable thickness steel. The seat hump was uniquely secured with counter sunk bolts in countersunk washers. As the seat vinyl was suede and patterned one can only presume the marketing people had a big hand in design.

The A1R was successful when properly tuned and maintained but often owners had little two-stroke experience and mechanical knowledge and Kawasaki were very poor at supplying spare parts. Without the option of inter-changeable parts with the A1, reliability issues were a problem for some. Despite their many successes, Japanese over-the-counter racing motorcycles of the 1960s were often unfairly written about in a derisive manner. These motorcycles were designed to win national titles – which they did – and not to compete with exotic works GP machinery. With 40-plus bhp and a top speed of over 200km/h, A1Rs were winners in the right hands as was proved on many race circuits. In the 1967 German GP one finished 7th against the pukka multi-cylinder works bikes and another won the Japanese national title. Others were successful in the USA and British/European events. Factory specials to promote the 350cc A7 Avenger street bike were made and although successful were only over-bored A1Rs producing 53bhp and 220km/h. There was a later major update, the A1RA, but again a factory special. Although there were a number of Kawasaki race bikes often referred to as production or over-the-counter racers, the official Kawasaki catalogue lists the A1R and the H1R (500cc triple) as the only ones with the rest being factory specials for selected dealers/riders.

Did the A1R achieve Kawasaki’s aim of promoting the brand in Australia? Well in some states it did but in 1967 Adelaide was Australia’s third largest capital city with a very strong motorcycle community so the first South Australian Kawasaki agent, Ron Hewitt, brought in an A1R but after sitting in his shop window for a year it was sold to a Melbourne dealer. The same fate followed the H1R (500cc triple) when the then South Aust. Kawasaki agent, Geo. Bolton Motorcycles, brought one in only to have it sit in the showroom for a year before being sold to a Melbourne dealer. A genuine A1R is easily recognised by its obvious differences but for a final check, frame and engine numbers should match with the numbers starting with 5, i.e. A1 500XX. It is not known how many A1Rs were sold in Australia, but the author knows of four and one A1RA existing and there are always unknown ones lurking in sheds. Because of low numbers, unique design and lack of spare parts even in their day, A1Rs can be very difficult to restore and keep running. Whilst the paint scheme was impressive it was most unsuitable for a racing motorcycle that would end up on its side sliding along the track on numerous occasions. The featured A1R was sold new in Australia and was still being used in competition in 1971 but after some crashes and lack of spare parts, fell into a poor state. Its current owner, the author of this article, restored it to again be the prettiest of the 250cc Japanese production racers.